A Research Paper By Alison Mitchell, Leadership Coach, NETHERLANDS

School Staff Wellbeing – How the PROSPER Model of Positive Education Can Be Supported by Coaching Within Schools

Well-being has long been on the agenda in schools and the importance of having clear mental health and well-being policies is high. However, as post-pandemic funding has targeted the well-being of our students, has this left a gap in supporting the well-being of our educators?

In this paper, I will outline some of the current issues faced in schools globally, including staff retention and recruitment problems and low engagement across different education systems. Having briefly defined positive psychology and well-being, I will introduce the concept of having a clear framework for well-being in schools, in this case, the PROSPER model. I will then go on to show ways in which coaching in schools could help develop and sustain this framework to embed a positive culture, focused on the well-being of the school staff.

The focus of this paper is on adults in school settings. The framework can also be used to focus on student well-being. Whilst much of the research on wellbeing in schools has focused on the impact of interventions on the target group, i.e. impact of teacher wellbeing initiatives on teachers, or the impact of student wellbeing initiatives on students, there is a growing number of studies into how increasing teacher wellbeing can impact the outcomes of students.

What’s the Problem?

Teacher recruitment and retention is a global issue. In England, studies have pointed to the fact that only 60% of teachers remain in the profession after 5 years. Given that a teacher may have trained for 4 years this is a dismal statistic. In an international review of research on teacher retention, See, Beng & Morris (2020) found that financial incentives had little benefit. The workload was a key indicator in teachers leaving the profession early, and perception of this workload was an indicator of the difficulty in recruitment. Although there were limited studies available in the research, a focus on developing positive school cultures was effective. It was suggested that whilst there were very few rigorous studies that evaluated interventions related to areas such as accountability, teacher stress, working conditions, behavior, workload, or levels of support from teachers/leaders, some of the correlational and survey-based studies indicate that these could be valuable areas to explore further.

Staff shortages lead to increased stress on the school system, with negative impacts on both staff and students, alongside further difficulty in attracting new people to the profession.

Research is showing that early-career teachers are more likely to leave their jobs because of low job satisfaction, which can lead to a shortage of teachers (Green-Reese, Johnson, & Campbell, 1991). On the other hand, if teachers feel a high level of job satisfaction, they provide higher-quality teaching and their students are more successful (Demirtas, 2010).

If we do not ensure, first and foremost, that our teachers are feeling physically and mentally well, they cannot be their best for their students. Consequently, a school which does not prioritise staff wellbeing is disadvantageous to its own students. Tomesett & Uttley (2022)

The well-being of our staff in school underpins the learning that is happening within schools.

What Is Happening in School Staff Wellbeing?

There are many well-intentioned well-being initiatives in schools to support the staff, however many addresses the symptoms of the problem, not the root causes.

Brady and Wilson (2021) concluded from their qualitative study of teacher well-being policy in schools, that those initiatives that addressed promoting meaningful workloads, rather than one-off or limited-duration well-being activities were favored by teachers.

Introducing a Framework to Support Wellbeing

In order to attract and retain the very best professionals, and also to clearly set wellbeing at the center of a school’s culture, I believe school leaders have to create sustainable approaches to addressing the mental health and wellbeing of all stakeholders.

For too long, many schools have focused on the improvements that need to be made, rather than on what is already working well. The constant changes in curriculum, assessment and the monitoring of schools leave many reacting rather than proactively embedding a positive school culture that enhances the well-being of all.

Organizations have looked to the field of positive psychology to support school culture change. Positive psychology is a branch of psychology that focuses on the development of individual strengths instead of weaknesses. Instead of placing a focus on the components of mental illness, positive psychology focuses on how the positive events in a person’s life form their identity (Peterson, 2008)

For some time well-being has been a buzzword in schools, particularly in relation to children and young people, but now more recently, the focus has shifted to school staff. As previously mentioned, there is now more research into the link between teacher well-being and student outcomes. The results of a study by Carrol et al (2021) provided important preliminary evidence that students benefited when their teachers’ levels of stress and well-being meaningfully improved.

Martin Seligman is said by many to be a pioneer in the study of positive psychology. He has also studied wellbeing and came up with the idea that wellbeing consisted of five principles: positive emotion, engagement, meaning, positive relationships, and accomplishment. (PERMA model, Seligman 2011)

Other researchers have argued that in order to live well we need to consider different elements of our life. Tom Rath, co-author of Wellbeing: The Five Essential Elements, considered overall happiness as a product of well-being in five distinct areas of life – finances, relationships, physical health, community, and career.

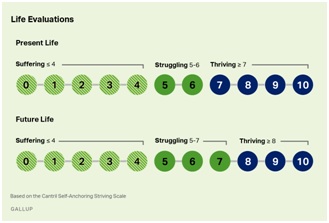

In their book Wellbeing at Work (2021), authors Jim Clifton and Jim Haryter introduced the concept of measuring well-being. This is a simple tool to look at the present and future happiness on a scale between 0 (worst possible life) and 10 (best possible life). This could be useful for schools wanting to measure the impact of well-being interventions.

The PROSPER Model

For the purpose of this paper, I have chosen the PROSPER framework. Like Seligman’s PERMA model, the authors, Noble & McGrath (2015) developed a multi-faceted framework for prioritizing student well-being in schools. This was developed to address student well-being but could be equally valuable for use with school staff.

The following outlines the seven components of the PROSPER framework. In each section, I will briefly review some of the existing practices that go on in schools and offer suggestions as to how coaching and coaching questions could support each strand.

Positivity

Positive emotions include feeling safe, a sense of belonging, feeling interested, content, and cheerful. Enhancing positivity also involves developing a capacity for gratitude and appreciation. Appreciative inquiry can be used in schools in many different ways. A first step would be to replace traditional observations with learning walks to observe what is working well. Behavior management is a key area in schools, and appreciative inquiry can be used to find out from the student and other teachers what works well when starving towards positive behavior.

Many well-being initiatives in schools fall into this area of the PROSPER model. Random acts of kindness for colleagues are one initiative that is used successfully in schools. Others might display the Action for Happiness calendars in classrooms and staff areas, to focus on different positive emotions throughout the year eg Happier January, Self-care September (https://actionforhappiness.org/all-calendars)

If schools are embedding a coaching culture, positivity can be explored during coaching conversations using the following questions

- What’s going great this week?

- What have you accomplished so far?

- What are three good things that happened at work?

- What are you grateful for today?

- What are you feeling really good about?

Relationships

The second area of the PROSPER model is that of relationships. In a school community, relationships are key to success. There are many relationships to consider eg pupil to pupil, pupils to a teacher, leader to the team, parent to teacher, etc.

Whilst being a people-focused organization, a school can also be a lonely place for individual members of staff, with a lot of time spent isolated from other colleagues. Schools need to create opportunities for staff to work and socialize together. Inviting staff rooms, staff work areas, and social occasions all help to promote relationships as being important. A recent study by Gallup (2022) indicates the importance of having a “best friend at work”. School leaders need to allow this by intentionally creating opportunities for collaboration and communication. Knowing that another colleague is looking out for you is key to engagement, supports a safe working environment, leads to innovative problem-solving, and creates more fun at work.

Access to a coach can also be the supportive relationship that an individual needs to improve his or her well-being. Within a team coaching conversation, the following questions could be useful

- What can we do to maintain our positive relationship?

- If we don’t agree on something, what approach works best for us to create alignment?

- What do you see that works well when we work together?

Developing a strengths-based coaching culture (see below) also develops an in-depth appreciation of the needs of other members of staff, leading to positive relationship building.

Outcomes

Educators need clear, realistic goals which have an endpoint. This promotes a sense of purpose and achievement. All too often in schools, we see the goals change frequently, creating frustration, confusion, and loss of direction. Coaching allows members of staff to set goals for themselves. In coaching conversations ways of reaching these goals, and keeping accountability can be broken down, empowering the individual to set clear direction and work purposefully towards these outcomes. Coaching can also help the individual see different possibilities towards reaching the goals, perhaps shifting perspective or a mindset change. When educators are supported in setting clear goals, working towards them, and producing an outcome, they will also transfer this to their students.

Strengths

A focus on strengths in a school identifies and values the differing strengths of the whole school community. In order to have well-being as a priority in a school, it would be beneficial for all school staff to know their own strengths and that of others.

A focus on strengths in a school identifies and values the differing strengths of the whole school community. In order to have well-being as a priority in a school, it would be beneficial for all school staff to know their own strengths and that of others.

When school staff is recognized for their unique contribution to the whole school community there is a shift in engagement.

Embedding a strengths-based coaching culture in schools can have positive effects. According to research done over 50 years by Gallup using their strengthsfinder assessment, when people are encouraged to develop their strengths they

- experience positive energy

- are more likely to achieve their goals

- are more confident

- perform better at work

- are more engaged at work

- experience less stress

Some examples of strengths-based coaching questions could be

- What do you get complimented on?

- What could be the strengths that lie underneath?

- When have you felt most energized? What were you doing?

- What do you do better than others?

- What small things do you do that you find extremely satisfying?

- What strengths could this point to?

Purpose

Simon Sinek advocates that whilst metrics and milestones are really important (thinking about goals and outcomes) there must be a purpose behind them. The coaching staff in schools can help identify their purpose, both professionally and personally. For maximum effectiveness, I believe all school staff should be offered coaching, either individually or in groups to enable them to fine-tune their purpose. This, linked to the shared purpose of the school, will support goal setting.

Engagement

The key to more staff engagement is to harness the power of staff having opportunities to use the strengths and talents that they possess. It is known that working within our favored strengths leads to more energy, ease, excellence, and engagement. Once staff has been supported in identifying their strengths, coaches in the school can help the member of staff find different ways of doing things to create more engagement. Coaching questions could be

- What gives you energy?

- What drains you?

- When do you feel in flow?

- What strengths are you using when you feel you excel?

Resilience

Resilience includes having the capacity to ‘bounce back after setbacks, mistakes, and difficulties and being courageous when faced with challenging situations. There is also a focus on coping skills and implementing support structures. Access to external coaching in schools, or the development of internal coaches enables staff to develop these mechanisms for themselves when faced with issues. With the ever-changing demons of school staff, focusing on developing resilience is very important. Coaching questions that could bring about change could be

- What is going well, and how can you leverage this going forward?

- If you could move one obstacle out of your way, what possibilities could that reveal?

- A year from now, what would you like to be different for you? The same?

The Importance of Wellbeing and Engagement Interventions for Our School Staff.

I have given a very brief overview of the importance of well-being and engagement interventions for our school staff. I propose developing a strengths-based coaching culture within schools that starts with the staff and permeates all stakeholders. By using a framework such as the PROSPER model, schools can start to evaluate current practices against each area and track the effectiveness of initiatives. Access to high-quality coaching and the use of coaching language in schools will further allow real progress to be made in the area of wellbeing, hopefully leading to improved working conditions and a brighter picture for recruitment and retention of the school staff.

References

Carroll A., York A., Fynes-Clinton S., Sanders-O’Connor E., Flynn L., Bower J.M., Forrest K., Ziaei M. The Downstream Effects of Teacher Well-Being Programs: Improvements in Teachers’ Stress, Cognition and Well-Being Benefit Their Students. Front. Psychol. 2021;12:2615

Clifton, J & Harter, J. K. (2021) Wellbeing at Work: How to Build Resilient and Thriving Teams. Gallup Press

Demirtas, Z. (2010). Teachers’ Job Satisfaction Levels. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences Vol. 9, Pp. 1069–1073.

Green-Reese, S., Johnson, D. J., & Campbell, W. A. (1991). Teacher Job Satisfaction and Teacher Job Stress: School Size, Age and Teaching Experience. Education Vol. 112, No. 2, Pp. 247–252.

Noble, Toni & McGrath, Helen. (2015). Prosper: A New Framework for Positive Education. Psychology of Well-Being. 5. 10

Peterson, C. (2008, May 16). What Is Positive Psychology, and What Is It Not? Psychology Today.

Rath, T., & Harter, J. K. (2014). Wellbeing: The Five Essential Elements. Gallup.

See, Beng & Morris, Rebecca & Gorard, Stephen & Kokotsaki, Dimitra & Abdi, Sophia. (2020). Teacher Recruitment and Retention: A Critical Review of International Evidence of Most Promising Interventions. Education Sciences. 10. 262. 10.3390/EDUCSCI10100262.

Seligman, M. E. (2011). Flourish. Free Press.

Tomsett J and Uttley J (2020) Putting Staff First. Woodbridge: John Catt.