A Research Paper By Austin Tay, Executive Coach, SINGAPORE

Psychological Flexibility in Coaching – Coaches Are There to Help Individuals to Create That Equilibrium

As humans, we are all wired to fight or flight response (aka acute stress response – Cannon, 1929). We react to danger, uncomfortable situations and negative thinking either by running away or staying put to “fight”. Our preference is to bring equilibrium to our lives to feel and think comfortably and back to the status quo.

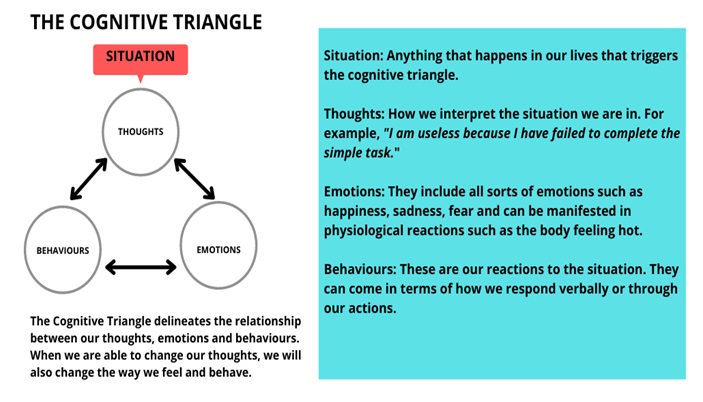

In the context of coaching, coaches are there to help individuals to create that equilibrium. The coach role is not to guide, lead or instruct how individuals are supposed to think, feel and change their behaviour. Instead, the coach’s role is primarily to be the sounding board for those individuals. The coach asks those questions to help individuals have self-awareness or self-realisation to see and understand what is stopping them from moving forward. One model that is helpful for individuals to move from a state of stuckness to unstuckness is the Cognitive Triangle.

Genesis – The Cognitive Triangle

The Cognitive Triangle is core to the Cognitive Model of Depression that Dr Aaron Beckproposed (Beck, 1967). Beck’s model focused on automatic thoughts, schemas and cognitive distortions (Beck & Freeman, 1990). Automatic thoughts occur based on how an individual assessment of a given situation. These thoughts will, in turn, evoke an individual’s emotions and response to that given situation. Unfortunately, as these thoughts are automatic, they are often left unchecked and accepted by an individual as truth.

When individuals accept their automatic thoughts and conceptualise their situation through their interpretations, such interpretations are known as schemas. These schemas determine individuals’ automatic responses.

Individuals’ schema can cause cognitive distortions. For example, individuals continue to accept and confirm maladaptive schemas despite being presented with contrary evidence. Beck and his colleagues classified the following distortions: dichotomous thinking (seeing things as black or white); personalisation (an individual interprets external events to be directly related to oneself); overgeneralisation (associating isolated incidents to all or many other situations); and catastrophising (treating adverse events as catastrophes even when they are minor problems).

In summary, cognitive distortions cause individuals to become judgmental, take the extreme interpretations of their situations. These causes, in turn, become their generalised schemas that lead to automatic thoughts and feelings. Therefore, cognitive therapy can help individuals break out from the vicious cycle of their self-supporting and maladaptive cognitions.

Application – The Cognitive Triangle

The Cognitive Triangle encourages an individual to identify the thoughts, feelings and behaviours that transpire within a situation. The typical pattern an individual will show is quick to associate negative thoughts, negative emotions, and behaviour with supporting those thoughts and feelings. The association is where an individual end up with a thinking pattern that might not necessarily be accurate. That is to say, an individual has created a thinking mistake.

The Cognitive Triangle encourages an individual to identify the thoughts, feelings and behaviours that transpire within a situation. The typical pattern an individual will show is quick to associate negative thoughts, negative emotions, and behaviour with supporting those thoughts and feelings. The association is where an individual end up with a thinking pattern that might not necessarily be accurate. That is to say, an individual has created a thinking mistake.

In coaching, a coach will need to listen actively and observe the client (if done using video). A present coach will pick up cues from the client that will help the coach formulate those questions about the client’s thinking, feelings, and behaviours. When the coach asks questions relating to the client’s thoughts, feelings and behaviour, it can help the client be aware of and address their thoughts, feelings and behaviours. The result can benefit the client.

The client will start to move forward and get out from the stuckness by replacing those inaccurate thoughts, feelings and behaviour with positive ones. Following this type of positive trajectory aligns with what proponents of positive psychology believe in – identifying and exploring negative thoughts, emotions, and behaviours and understanding that being positive can achieve goals and objectives.

While it is great to see that a client has taken a shift in their mindset and embraced positivity, however, in reality, the overemphasis on positive thinking can at times be detrimental. For example, an individual is faced with a health problem but refuses to consult a doctor, thinking that everything will be alright because he believes he is healthy enough to weather the health crisis. Unfortunately, this inaction can lead to a devastating outcome if the health problem is malignant. So what other options do we have then?

Another possible way individuals can help themselves deal with negative thoughts and emotions is to learn to accept that they are part of who they are. These thoughts and emotions are not going away; they will retreat but resurface again when opportunities strike. Thus, individuals should focus on what matters to them instead of constantly fighting or pretending that these thoughts and emotions do not exist (through positive thinking). When individuals can focus on what matters to them, they will spend their time attaining the goal they set for themselves. Getting out of their vicious cycle of rumination, individuals need to be in the present moment, accept their circumstances and commit to the actions that will bring them to the goals they set for themselves. When individuals can do all these, they become psychologically flexible.

Alternative – Acceptance and Commitment Therapy

Psychological flexibility derives from the third wave of cognitive behaviour therapy, Acceptance and Commitment Therapy.

Acceptance Commitment Therapy (usually spoken of as ACT, rather than as A.C.T.) describes itself as ‘an extensive empirical, theoretical, and philosophical research program that demonstrates how language embroils clients in a fight with themselves and their experience‘. (Hayes and colleagues, 1999). This therapy is rooted deeply in the philosophical foundation of behavioural analysis known as functional contextualism and relational frame theory(RFT; Hayes, Barnes-Holmes, & Roche, 2001; Hayes and colleagues, 1999)that delineates how language influences cognition, emotion, and behaviour.

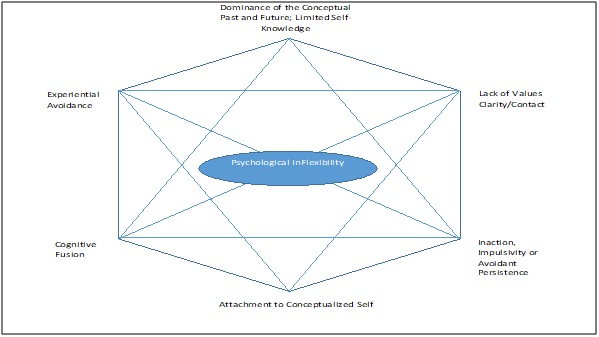

The ACT psychological flexibility model (or unified model) is a set of coherent processes that applies with precision, scope and depth to a wide range of clinically relevant problems and issues of human functioning and adaptability. (Hayes, Strosahl& Wilson, 2012). ACT’s purpose is to increase the psychological flexibility of a person by helping them to be in contact with the present more fully and as a conscious human being, and, based on what the situation affords, to change or persist in behaviour to achieve valued ends. (Hayes &Strosahl, 2004). To understand how the psychological flexibility model works, one should start with psychological inflexibility (see Figure 1).

Psychological Inflexibility

The ACT model of psychological inflexibility is also known as an ACT model of psychopathology. According to Hayes and his colleagues (2006), each point, as shown on the hexagon diagram above, corresponds to one of the six processes hypothesised to cause human suffering and psychopathology. As depicted in the middle of the model, psychological inflexibility is the cumulative interaction of all the processes. The six processes are: 1) experiential avoidance; 2) cognitive fusion; 3) dominance of the conceptualised past and future and limited self-knowledge; 4) attachment to the conceptualised self; 5) lack of values clarity or contact; 6) inaction, impulsivity, or avoidant persistence.

Experiential Avoidance

Experiential avoidance is the ‘attempt to control or alter the form, frequency, or situational sensitivity of thoughts, feelings, sensations or memories. (Hayes, Wilson, Gifford, Follette, &Strosahl, 1996). Accordingly, experiential avoidance is a by-product of one’s ability to evaluate, predict and avoid events through cognition and language. When individuals can forecast and evaluate, they will categorize their feelings and consider what good or bad experiences are. When given a choice, an individual is likely to think about good instead of bad experiences. Such avoidance, however, can, in some instances, be paradoxical. For example, when one suppresses a negative thought, Y, this action is accompanied by an unwritten rule not to think about Y. However, specifying Y also tends to evoke thoughts about Y. Similarly, trying to suppress emotions will only produce the emotions. Thus, in both of these situations, being experientially avoidant will be fruitless.

Cognitive Fusion

Cognitive fusion means an individual’s propensity to get stuck in the content of his thoughts, thus hindering himself from using other means to help himself or adjust his behaviour. It is a natural process when a person starts to think. However, this can become problematic when that person’s thoughts become fused. That is to say, that person will be looking at the world through a coloured lens tainted with the language associated with the thought.

The Dominance of the Conceptualized Past and Future; Limited Self-Knowledge

Humans spend too much time contemplating failures in the past and fear the future. This rumination leads to cognitive fusion and experiential avoidance. The presence of cognitive fusion and experiential avoidance pulls a person away from an awareness of her present private experience. For example, the feelings, thoughts and sensing one experiences at the present moment are readily replaced by the past experiences of emotions such as fear, anger and sadness. This form of cognitive fusion creates experiential avoidance, as evidenced by research on experiential avoidance and alexithymia, which were highly correlated. (Hayes and colleagues, 2004; Hayes and colleagues, 2006)

Attachment to the Conceptualised Self

Humans learn verbal processes to describe themselves from an early age, such as how old we are, what we like, and dislike. These verbal processes gradually become our mode of communication with others. With the ability to formulate, describe, predict and evaluate, information becomes a constant story. We add and subtract layers relate to what we have done, what we have learned and what problems we are having. In doing this, we build a ‘conceptualised self’ in this process of storytelling. (Hayes and colleagues, 1999). The ‘conceptualised self’ thus will only believe what has been evaluated and articulated. This belief is a juxtaposition of how we verbally and objectively perceive an event. Therefore, what appears to be real as told by our internalised storyteller can only be ‘real’ in the context of our concoction concerning a circumstance. Consequently, the stories do not provide real solutions to any impending issues, leading to the ‘conceptualised self’ feeling stuck because inflexible behavioural patterns constrict it.

Lack of Values Clarity or Contact

According to Hayes and colleagues (2004), values are qualities of life represented by ongoing patterns of our behaviour. To these researchers, values are about how we choose to live our lives in a meaningful way, and values are also the compass that helps us navigate our lives. Values, unlike goals, are not evaluated. Instead, they serve as a standard for other things to be evaluated. When someone experiences experiential avoidance, they will find it challenging to determine what is essential in their life. For example, if someone grew up without experiencing affections, it is not likely that they will outwardly show care and concern to others because choosing not to care seems to be a better option.

Inaction, Impulsivity, or Avoidant Persistence

When a person has chosen not to do anything about or react impulsively to his stuck thoughts, he sabotages the opportunity to work towards value-actioned goals. All these inflexible approaches bring only short term relief, which can cripple one’s abilities to look at other positive and possible goals that could enrich and provide more significant meaning to one’s life.

The Culmination of Six Core Problems

Each of the six core problems delineated contributes to psychological inflexibility. When we are too caught up with thoughts, feelings and emotions, we are trapped in a continuous cycle that prevents us from being present. We will not be able to step out and take stock of the situation. The time we spent ruminating about the past and worrying about the future takes us away from living our lives following what matters to us most.

Psychological Flexibility

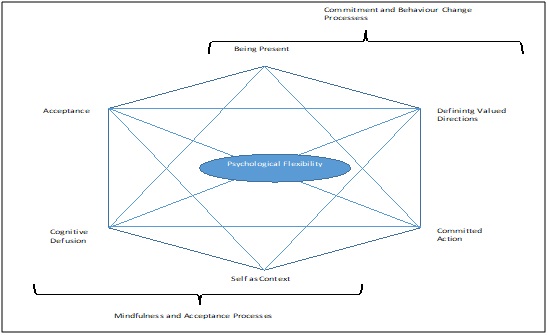

We will next describe the six therapeutic processes of ACT that promote psychological flexibility. The six therapeutic processes are 1) Acceptance; 2) Cognitive Defusion; 3) Being Present; 4) Self as Context; 5) Defining Valued Directions, and 6) Committed Action. (see Figure 2).

Acceptance

Acceptance in the ACT is the opposite of experiential avoidance. Instead of running away from events, an individual is encouraged to embrace them as they are and not try to alter the events, which usually would cause unnecessary psychological harm. For example, anxious people learned to treat anxiety as nothing more than a feeling and not fight it. Acceptance is not a panacea; it is a method to help individuals move towards values-based actions. Acceptance methods include exercises that expose individuals to previously avoided events without falling back to their accustomed safety behaviours. For example, exercises entitled the tin can monster, the unwanted party guest, and passengers on the bus (see Association For Contextual Behavioural Science).

Cognitive Defusion

We learn that when we fuse our thoughts, feelings and emotions, we naturally get stuck spiralling downwards into an abyss. To prevent ourselves from getting stuck, we need to learn how to get ourselves ‘unstuck’ in those situations—defusing a context that is not literal means disentanglements of thoughts, which creates behavioural flexibility linked to chosen values.

Being Present

When one is in a problem-solving mode, one will spend less time contacting the present instead of rationalising how these events have resulted from their current consequences. Instead, they will attempt to visualise and look for solutions that will enable them to mould an ideal future. On the contrary, when a person is in contact with the present moment, they can respond flexibly and be open to new possibilities within the current situation. They can defuse ongoing thoughts, feelings and emotions in a non-judgmental manner – also known as ‘self-as process’ (Hayes and colleagues, 1999).

Self-As-Context

Self-as-context is when an individual starts to experience the ‘Separate from the content of the events. The therapist will use metaphors or experiential exercises such as letting go of identity (Walser and Westrup, 2007). Through this process, individuals will be able to get a better sense of themselves and become observers. This process is also known as ‘perspective taking’ (McHugh & Stewart, 2012), where they can see their experience. As Hayes and colleagues (1999) put it,

When people are asked many questions about their history or experience, the only thing that will be consistent is not the content of the answer but the context or perspective in which the answer occurs. “I”, in some meaningful sense is the location that is left when all the content differences are subtracted. (p.185).

According to Luomaand colleagues (2007), consciousness and awareness are not easy to access; there is a need to look at human language. They believe that language can lead to a sense of transcendence, which is a spiritual aspect of human experience. According to these researchers, having a transcendent sense of self allows individuals to be aware of their experiences but not attached to them. That is to say, self-as-context is the locus where an individual observes (perspective taking) the ongoing and yet free of entanglements.

Defining Valued Directions

ACT, unlike CBT, is a therapy that encourages individuals to move towards valued living. Instead of being a passive passenger on the journey to psychological flexibility and being enslaved by their inner experiences, individuals will engage in actions that will move them towards who and what they choose to be vital to them in their lives. To do this, individuals will need to select the values that they view are important to them. Individuals’ values are freely chosen rather than forced upon them by their circumstances or other people. Unlike goals, values do not have an expiry date; they do not get crossed out once achieved. Living a valued life is about enjoying the present as one works towards the goal.

Committed Action

When individuals are not psychologically flexible, they are unlikely to develop and sustain actions that align with their values. In the ACT, committed actions are called values-based actions designed to create a pattern of action that is itself values-based (p 95, Hayes and colleagues, 2012). To these researchers, behaviours are constantly redirected to create larger and larger patterns of flexible and effective values-based behaviour. That is to say; individuals will evaluate, moderate and modify their behaviours to achieve the goals they have set.

Psychological Flexibility

In summary, when the six therapeutic processes come together, an individual will become psychologically flexible. That is ‘contacting the present moment as a conscious human being, fully and without needless defence – as it is and not as what it says it is – and persisting with or changing a behaviour in the service of chosen values.’ (p, 96 Hayes and colleagues, 2012)

Psychological Flexibility in Coaching Methods

Coaches aim to move clients from a place of stuckness to another that is filled with possibilities. Coaches can use various types of methods to do so. However, for clients to accept their negative thoughts and emotions can accelerate their process of moving forward, which can make them focus on the important things they value in life. When clients can do so, they become psychologically flexible.

References

Cannon, W. B. Bodily changes in pain, hunger, fear and rage. Appleton.

Beck, A. T. Depression – Clinical Experimental and Theoretical Aspects, New York: Harper and Row.

Beck, A. T., & Freeman, A. Cognitive Therapy of Personality Disorders. New York: Guilford.

Beck, J. S. Cognitive behaviour therapy (3rd ed.). Guilford Press.

Hayes, S. C., Wilson, K. G., Gifford, E. V., Follette, V. M., & Strosahl, K. Experiential avoidance and behavioural disorders: A functional dimensional approach to diagnosis and treatment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology

Hayes, S. C., Strosahl, K. D.,&Wilson, K. G. Acceptance and commitment therapy: An experiential approach to behaviour change.NewYork: GuilfordPress

Hayes, S. C., Barnes-Holmes, D., & Roche, B. (Eds.). Relational frame theory: A post-Skinnerianaccountofhumanlanguageandcognition. New York: PlenumPress.

Hayes, S. C., Follette, V. M., & Linehan, M. M. (Eds.). Mindfulness and acceptance: Expanding the cognitive-behavioural tradition. New York: Guilford Press.

Hayes, S. C., Luoma, J. B., Bond, F., W., Masuda, A., & Lillis, J. Acceptance and commitment therapy: Model, processes and outcomes. Behaviour Research and Therapy

Hayes, S. C, Strosahl, K.D., & Wilson, K. G. Acceptance and commitment therapy: The process and practice of mindful change (2nd edition). New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

Luoma, J. B., Hayes, S. C., & Walser, D. W. Learning ACT: an acceptance and commitment therapy skills training manual for therapists. The USA. New Harbinger Press.

McHugh, L., Stewart, I. The self and perspective taking: Contributions and applications from modern behavioural science. Oakland, CA: Context Press.

Walser, R., & Westrup, D. Acceptance & Commitment Therapy for the Treatment of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder & Trauma-Related Problems: A Practitioner's Guide to Using Mindfulness & Acceptance Strategies. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger.