Research Paper By Patricia Hudak

(ADHD Coach, USA)

Introduction

Imagine, if you can, getting ready to go back to school. It’s the beginning of September, you’ve enjoyed the summer spending time with family and friends – and you have a heavy feeling in the pit of your stomach that you KNOW will not disappear no matter how much you wish it away. It will only get worse when school begins and what you are now only imagining becomes a reality: it’s difficult to pay attention in class, you forget to write down your homework, and you get home knowing there are assignments that need to be completed if only you could remember what they are or, if you do remember, you don’t know where to begin. This is the typical scenario for students diagnosed with Attention Deficit Hyperactive Disorder (ADHD), an accurate description of the angst these clients feel all the time.

Understanding ADHD

Working with clients diagnosed with ADHD requires coaches to apply the same competencies as in any other coaching situation. However, it is important to understand the unique ways in which an ADHD diagnosis affects the client’s view of the world and his or her place in it. It is an especially critical consideration when working with ADHD students desiring to set goals and apply strategies for achieving those goals, both personally and academically. The coach must understand the challenges of ADHD and be able to communicate them to the student.

Medical Diagnosis

ADHD is characterized by a pattern of behavior that can negatively affect performance in social, educational, or work settings. It is one of the most common neurodevelopmental disorders of childhood. Researchers believe that problematic brain chemistry is what causes challenges to a person’s executive functioning skills, which result in behaviors such as failure to pay close attention to details, difficulty organizing tasks and activities, excessive talking, fidgeting, or an inability to remain seated in appropriate situations.

The American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, Fifth edition (DSM-5), is used by mental health professionals to help diagnose ADHD. Based on the symptoms presented (relating to hyperactivity, impulsivity, and/or inattention), it categorizes types of ADHD as: Combined Presentation, Predominantly Inattentive Presentation, or Predominantly Hyperactive-Impulsive Presentation. Because symptoms can change over time, the presentation may change over time as well.

Executive Functioning Skills

Knowing there is a biological basis for ADHD is often reassuring to students. It helps them realize there is an explanation for their behaviors: they are not “lazy” or “stupid”, labels often applied when their performance in the classroom does not meet teachers’ expectations. This understanding also provides them with hope that there are ways to deal with this brain-based physiological problem.

The part of the brain that seems to be most affected in individuals with ADHD is the prefrontal cortex. This is the brain area responsible for managing a number of important skills needed to be successful in life. The term used to describe these skills is “executive function”. Drs. Joyce Cooper-Kahn and Laurie Dietzel, authors of Late, Lost, and Unprepared, describe executive functions as a “set of processes that all have to do with managing oneself and one’s resources … an umbrella term for the neurologically-based skills involving mental control and self-regulation.”

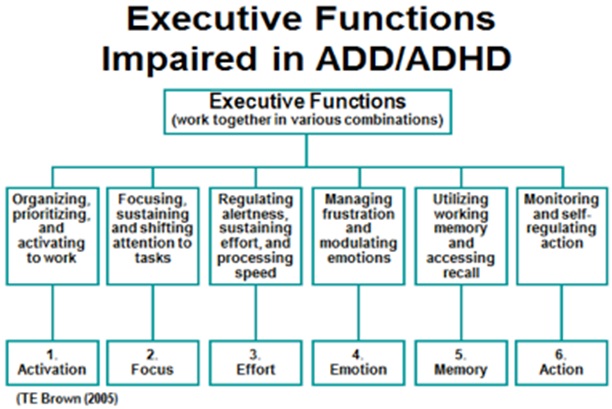

Dr. Thomas E. Brown created a model to visually explain executive functions as they relate to an ADHD diagnosis:

He also says, “While everyone has occasional impairments in their executive functions, individuals with ADHD experience much more difficulty in development and use of these functions than do most others of the same age and developmental level. Yet even those with severe ADHD usually have some activities where their executive functions work very well.”

He also says, “While everyone has occasional impairments in their executive functions, individuals with ADHD experience much more difficulty in development and use of these functions than do most others of the same age and developmental level. Yet even those with severe ADHD usually have some activities where their executive functions work very well.”

Treatment Plan

The treatment plan for students diagnosed with ADHD is often multi-modal: exercise, changes to diet, medication, psychotherapy and/or coaching. Working with the school system to include classroom accommodations can also ease the academic impact of an ADHD diagnosis. Regardless of the course of treatment, remembering that the disorder has a basis in a person’s brain can help coaches stay focused on measures that can help the student address and compensate for challenges to executive functioning due to the ADHD brain.

ADHD Coaching

One intervention that focuses directly on developing and enhancing important self-regulation skills and other executive functions is “ADHD coaching”. As with all other coaching, working with an ADHD student is a collaborative process built on a very special relationship between the client and the coach.

Coaches help individuals with ADHD by providing them with a clear understanding of the nature of ADHD and how it affects their daily life. They work with clients to identify important goals and to develop plans and strategies for achieving them. They help clients to monitor their progress towards these goals, identify when they are getting derailed, and develop strategies to more effectively pursue goals over time. Thus, coaches can help students develop their ability for effective self-regulated behavior, and provide an important external source of regulation as those abilities are developing.

The ADHD Student as a Client

There are significant variables, however, that make coaching ADHD students different from coaching other clients. Because ADHD is a developmental disorder in which brain maturation is delayed, the social maturity level of an ADHD student may be a few years behind that of their peers. They may have difficulty reading verbal and physical social cues, misinterpreting remarks, or not getting jokes or games. ADHD children are usually not aware of how immature or off-base they may seem to peers and adults. They cannot adequately read other people’s responses to their behavior. Desperate for positive attention, they may try behavior that is outrageous, funny, or negative, mistakenly believing it will gain them friends and respect. They may be ostracized by their peers and singled out by teachers, which hurts their self-esteem.

This emotional component affects the ADHD student’s interaction with others, including the coach. In Dr. Brown’s 2014 book, Smart but Stuck: Emotions in Teens and Adults with ADHD, he points out:

“To fully understand the role of emotions in ADHD, we must not only recognize that those with the disorder often have a hard time managing how they express their emotions but also acknowledge the critical role that emotions, both positive and negative, play in the executive functions: initiating and prioritizing tasks, sustaining or shifting interest and effort, holding thoughts in active memory, choosing to engage in or avoid a task or situation. Emotions—sometimes conscious, more often unconscious—serve to motivate cognitive activity that shapes a person’s experience and action. For those with ADHD, chronic problems with recognizing and responding to various emotions tend to be a primary factor in their difficulties with managing daily life.”

Additionally, compared to adolescents without ADHD, adolescents with ADHD are more likely to report experiencing victimization by peers and participating in bullying others. Among adolescents with ADHD, those who had experienced victimization by peers perceive lower levels of social support and have higher levels of parent-reported peer relations problems. As students get older, moving through middle and high school and beyond, significant differences in self-esteem have been noted between college students self-identified as ADHD and the general college population.

The ADHD student client brings a plethora of issues and concerns to the coaching relationship, and often “just wants to be normal”.

Challenges for the Coach

The coach guides the client through the coaching process, following established ethical guidelines and professional standards. As in all coaching relationship, the coach creates a safe, supportive environment that produces ongoing mutual respect and trust.

The client always sets the agenda, and for an ADHD student the goals may be general or specific to schoolwork. The coach typically works with the student in the areas of scheduling, goal setting, confidence building, organizing, focusing, prioritizing, and persisting at tasks – all key to helping address the problems in executive functioning that students with ADHD experience.

The specialized ADHD coaching environment, however, presents some unique challenges for the coach: because of the executive dysfunction, there is an increased likelihood that the client will be unable to set goals and make plans to achieve those goals, including establishing priorities. Coaching sessions require a greater focus on building skills and strategies to support the client’s need for consistent routine and structure. This often includes teaching and fostering appropriate social skills, self-discipline, self-reliance, and self-advocacy. Additionally, a higher level of accountability is essential to promote increased self-esteem and to empower the client to self-advocate and put the strategies into place so they become habits.

A Unique Approach to Coaching

To meet the distinctive needs of the ADHD student population, the coaching model employed in a 2011 study has great intuitive appeal. The focus on academic goal setting, progress monitoring, dividing long-term projects into a sequence of specific and manageable tasks – along with frequent contact to help students stay on track – is consistent with the consensus of ADHD as a disorder of executive functioning.

Successfully used by many ADHD coaches, the approach is simple and effective. Building on the typical life coaching relationship, there is sufficient structure to help clients experience success, build on that success, develop self-confidence, and experience a track record of accomplishments which enhance personal pride and self-image:

Conclusion

Coaching ADHD students is a unique opportunity to support growth and change in a portion of the population that is often dismissed. These individuals are bright and creative and generally eager to find ways to overcome the obstacles an ADHD-diagnosis puts in their way. Their journey begins with knowing what “ADHD” is and how the ADHD brain impacts their ability to perform executive functions, continues through their own self-awareness and discovery process, and ultimately ends with their empowerment to independently prepare for the future.

A coach of ADHD students finds much joy in the coaching process: establishing a trusting, mutual respectful partnership with individuals who may not have a strong sense of self-worth; guiding and supporting them in discovering the wonderful strengths that lie within; championing as the they take chances by freely exploring their own goals and aspirations; and finally seeing the self-confidence grow as the students begin to believe they can do ANYTHING to achieve their full potential and fulfill their life dreams. This unique coaching opportunity is the chance to make a difference – an exceptional opportunity to have an impact on how adolescents and young adults see themselves and their place in the world; to facilitate the movement of debilitating negative feelings and perceptions to powerfully positive outcomes as students successfully and happily pass into adulthood.

References

American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition. Arlington, VA., American Psychiatric Association, 2013.

Brown, Thomas E. Attention Deficit Disorder: The Unfocused Mind in Children and Adults. New Haven: Yale UP, 2005.

Brown, Thomas E. Smart but Stuck: Emotions in Teens and Adults with ADHD. Josey-Bass, 2014.

Cooper-Kahn, Joyce. Late, Lost and Unprepared. Bethesda: Woodbine House, 2008.

Dawson, Peg, and Richard Guare. Smart but Scattered. New York: Guilford, 2009.

Dooling-Litfin, Jodi K., and Lee A. Rosén. "Self-esteem in college students with a childhood history of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder." Journal of College Student Psychotherapy 11.4 (1997): 69-82.

Prevatt, Frances, PhD., and Jiyoon Lee. "Challenges in Conducting ADHD Coaching with College Students: A Case Study." The ADHD Report 17.4 (2009): 4-8. ProQuest. Web. 1 Oct. 2014.

Sleeper-Triplett, Jodi, MCC. Empowering Youth With ADHD: Your Guide to Coaching Adolescents and Young Adults for Coaches, Parents, and Professionals. Specialty Press/A.D.D. Warehouse, 2010.

Timmermanis, Victoria, and Judith Wiener. "Social correlates of bullying in adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder." Canadian Journal of School Psychology (2011): 0829573511423212.

Weyandt, Lisa L., and George DuPaul. "ADHD in college students." Journal of Attention Disorders 10.1 (2006): 9-19.