A Research Paper By Anina Knecht, Life Coach, SWITZERLAND

In my coaching model piece “The Growth Model” I have touched on that key moment in a coaching session that for me is when clarity comes to the client and a shift in perspective becomes possible. A shift usually from a limiting, heavy, significant viewpoint to a new, lighter, possibly bringing a perspective that allows the client to open their mind to broader and more holistic ways of thinking. I have explored this further in my Power Tool “Perspective vs. Heaviness”.

And if you are interested in what’s happening in the brain from a neurophysiological point of view when we shift perspectives or change behaviors, feel free to read on.

Brain plasticity is a two-way street; it’s just as easy to generate negative changes as positive ones. Vineet Singh

Theory

What are Perspectives and Habitual Behaviors?

In the dictionary, the term perspective is defined as a particular way of considering something, a point of view, a mental view, or a prospect.[1]Because we all have our very own view of the world and are shaped by our individual experiences in life, we consciously, and more often unconsciously, give significance to this particular reality we have formed for ourselves. This reality or perspective is a result of our history, experiences, and beliefs. Our unique perspective serves us assort of a mental shortcut and has the advantage that we can go about our lives without having to think in detail about everything that we think and do.[2]

According to Benjamin Gardner and Amanda L. Rebar “within psychology, the term habit refers to a process whereby contexts prompt action automatically, through activation of mental context–action associations learned through prior performances”. In other words, habitual behavior (e.g., tasks performed repeatedly)is triggered by impulses and requires minimal cognitive effort, awareness, or control. When an initially intentional behavior becomes habitual, the conscious action of a person becomes a context-cued impulse-driven mechanism. When the same context is encountered in the future, the habitual behavior is triggered spontaneously and the action is detached from cognitive awareness or control (i.e., we tie our shoes, walk to the bus stop or drive the car without thinking about these habituated tasks). According to Gardner and Rebar, as a consequence alternative behavioral responses become less consciously accessible.[3]

How do Perspectives and Habits Form in the Brain from a Neurophysiological Aspect?

Brain plasticity, also known as neuroplasticity, is a term that refers to the brain’s ability to change and adapt as a result of experience. Neuro refers to neurons, the nerve cells that are the building blocks of the brain and nervous system, and plasticity refers to the brain’s malleability.[4]Just like the stretch of an elastic band, our brains flex and adapt throughout our life. Both genetic and environmental interactions shape our brains and influence new behavior.[5]Neuroplasticity is ongoing throughout life, occurs as a product of learning and experience, and results in memory and habit formation.[6]

The first few years of a child’s life are a time of rapid brain growth. At birth, every neuron in the cerebral cortex has an estimated 2,500 synapses; by the age of three, this number has grown to 15,000 synapses per neuron. The brain tends to change a great deal during these early years of life as the immature brain grows and organizes itself. Generally, young brains tend to be more sensitive and responsive to experiences than much older brains. This promotes for example the ability to learn new things or the ability to enhance our existing cognitive capabilities in younger years.[7]

In comparison, the average adult has about half that number of synapses because as we gain new experiences, some connections are strengthened while others are eliminated. This process is known as synaptic pruning. Neurons that are used frequently develop stronger connections and those that are rarely or never used eventually die (like branches on a tree not being nourished). By developing new connections and pruning away weak ones, the brain can adapt to changing environments [8]and develop the neural networks associated with learning and memory.[9] As a consequence, adults also get more settled in their views, perspectives, and behaviors.

Brain changes are often seen as improvements, but this is not always the case.[10] In the same way, as it is used to form positive memory, learning, and experience, it can also lead to the creation of unwelcomed habits, patterns, and behaviors as well as limiting beliefs. This is why bad habits are so hard to break – we literally have to rewire the networks in our brain and allow the old habits (and their networks) to decay.[11] The good news though is that the brain never stops changing in response to learning throughout life. Some of the ways we can utilize neuroplasticity to encourage our brain to adapt and change in beneficial ways include learning environments that offer plenty of opportunities for focused attention, the unknown, and challenge. This can stimulate positive changes in the brain and consequently lead to habit changes or shifting from limiting heavy, significant viewpoints to new, lighter, possibility bringing perspectives.[12]

Where in the Brain do Perspectives and Habits Form from a Neurophysiological Aspect?

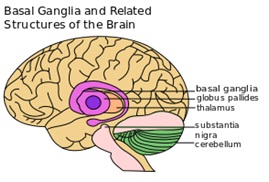

The “basal ganglia” refers to a group of subcortical nuclei within the brain responsible primarily for motor control, as well as other roles such as motor learning and emotional behaviors, and play an important role in reward and reinforcement, addictive behaviors, and habit formation.[13]

The basal ganglia are located at the base of the forebrain (cerebrum).[14] In the basal ganglia located deep in the brain’s core, habitual behavior is stored. The basal ganglia can function exceptionally well without applying conscious thought or action in a routine activity.[15]

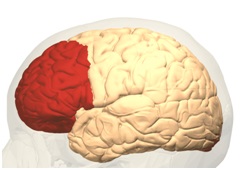

The prefrontal cortex (PFC) is the cerebral cortex covering the front part of the frontal lobe. This brain region has been associated with complex cognitive behavior, personality expression, decision making, and moderating social behavior. The basic activity of this brain region is considered to be the orchestration of thoughts and actions by internal goals. The most typical psychological term for functions carried out by the prefrontal cortex area is executive function. Executive function relates to the ability to differentiate among conflicting thoughts, to determine good and bad, same and different, future consequences of current activities, working toward a defined goal, prediction of outcomes, expectations based on actions, and social “control” (the ability to suppress urges that, if not suppressed, could lead to socially unacceptable outcomes). The prefrontal cortex supports concrete rule learning, while more anterior regions along the rostro-caudal axis of the frontal cortex support rule learning at higher levels of abstraction.[16]

The prefrontal cortex (PFC) is the cerebral cortex covering the front part of the frontal lobe. This brain region has been associated with complex cognitive behavior, personality expression, decision making, and moderating social behavior. The basic activity of this brain region is considered to be the orchestration of thoughts and actions by internal goals. The most typical psychological term for functions carried out by the prefrontal cortex area is executive function. Executive function relates to the ability to differentiate among conflicting thoughts, to determine good and bad, same and different, future consequences of current activities, working toward a defined goal, prediction of outcomes, expectations based on actions, and social “control” (the ability to suppress urges that, if not suppressed, could lead to socially unacceptable outcomes). The prefrontal cortex supports concrete rule learning, while more anterior regions along the rostro-caudal axis of the frontal cortex support rule learning at higher levels of abstraction.[16]

The prefrontal cortex employs much more energy than the basal ganglia. It is the brain’s center for rational thinking, which is energy-intensive and can only hold a limited amount of information at a time. It fatigues easily.[17] Because of this, any of our experiences receive broadly speaking the same treatment from our brain: A lightning-quick comparison with our existing mental database[18]to check against known context and consequent context-cued impulse-driven response.[19]This process is there out of necessity and enables us to cope with the sheer volume of information we encounter throughout the day.[20]

Behavioral Science Theory

Arguably the most famous theory in behavioral science was popularized by Nobel Laureate Daniel Kahneman.[21]At the center of his thinking is the “Dual Process Theory”, which asserts that thoughts can arise in two different ways, or as a result of two different processes.[22] He describes the processes as ‘thinking fast and slow’ otherwise known as System 1 (Intuition) and System 2 (Reasoning) Type Thinking.[23]According to him, intuition (or System 1)is fast and automatic, usually with strong emotional bonds included in the reasoning process and based on our inherent perception of the world around us. Kahneman says that this kind of reasoning is based on formed habits and is very difficult to change or manipulate. Reasoning (or System 2) is the slower and analytical mode, where reason dominates and which is much more volatile, being subject to conscious mental application.[24]

Overview: System 1 vs. System 2 Type Thinking[25]

| System 1 | System 2 | |

| Known as | Thinking Fast and System 1 Type Thinking | Thinking Slow and System 2 Type Thinking |

| Define | “A perceptual and intuitive system, generating involuntary impressions that do not need to be expressed in words. This system is fast to react, automatic, associative, emotional, effortless and learns through repeated experiences and gradually over time.” – Orlando Wood, System1 Group |

“The conscious, reasoning self that has beliefs, makes choices and decides what to think about and what to do.” Allocates attention to the effortful mental activities that demand it, including complex computations. |

| Examples |

Driving a bike or a car Walking to the regular bus stop without having to use a map to find it |

Learning how to drive a bike or car for the first time Giving a tourist direction |

| Ease of use | We are often happy enough to trust a plausible (System 1) gut judgment that comes easily to mind | It is hard work to process information using System 2and our capacity for System 2 Type Thinking is very limited |

| Control | System 1 is the process that is really in charge as it “effortlessly originates impressions and feelings that are the main sources of the explicit beliefs and deliberate choices of System 2” | We have to actively engage System 2 Type Thinking |

| When the System runs | It is System 1 Type Thinking that is responsible for many of the everyday decisions, judgments, and purchases we make and explains many of the heuristics (shortcuts or rules of thumb) that are highlighted by behavioral economics. | We use System 2 to make rational decisions. It is this slower system that retrieves mental data and weighs the pros and cons for us. |

| Quick Comparison |

Daily decisions Unconscious Automatic Error-prone |

Complex decisions Conscious Effort Reliable |

Translating Kahneman’s behavioral science theory into a simplified neurophysiological view as outlined in Chapter III above, the System 1 Type Thinking (affective responses and emotional reactions) is located in the basal ganglia.[26]The mesolimbic pathway also referred to as the mesolimbic dopamine reward system connects to the basal ganglia.[27]This pathway is responsible for the release of dopamine. Given that human beings tend to seek instant gratification, dopamine plays a key role in “thinking fast”.[28]

To help construct its narrative, System 1 may also employ heuristics – processing and decision-making shortcuts that save time by using intuitive algorithms to generate approximate answers that are “good enough”. For example, if a decision feels good, we will assume it must be the right one. Or things we can remember are more relevant and important – and more likely to occur again. Heuristics are great when they result in a correct judgment (which they often do), but when they fail they can lead to cognitive bias – the tendency of us humans to interpret information or perceive ‘truth’ based on our own experiences and preferences. For example, our System 1 brain is biased according to how believable we personally find a conclusion, or it interprets information in a way that confirms our preconceptions.[29]

System 2 Type Thinking (analytic system of decision-making) is linked to the prefrontal, frontal and parietal cortex. This region is more associated with our complex reasoning and higher-order “slow” thinking.[30]One of System 2’s main challenges is that it has limited processing capability and consumes a significant amount of energy; hence it tends to idle in the background until called upon.[31]

Having said that, Kahneman readily admits that the simplicity of his theory has its shortcomings.[32]Dividing the brain into two distinct ‘systems’ may help simplify the complexities of cognition. In reality, however, it is the combination of information gathered from multiple systems – basial ganglia, mesolimbic pathway, and prefrontal, frontal and parietal cortex – that help to produce our decisions. In other words, while different regions may be more or less relevant for either System 1 or System 2 Type Thinking, neither hemisphere is restricted to solely System 1 or system 2decision-making. Unconscious processes such as emotions (System 1) for example play a vital role in our more logical reasoning (System 2), and it is this integrative approach that makes our decision-making meaningful, and often more effective and purposeful.[33]

Neurophysiological Perspective: What Happens in the Brain from a Neurophysiological View when we Change a Habit or Take on a New Perspective?

Neuroscience research suggests that System 1 Type Thinking accounts for up to 95% of our decisions each day using this fast, instinctive, emotional mode of thinking. System 1 continuously creates impressions, intuitions, and judgments based on our daily routines and behaviors.[34]In addition to that, as we have learned in Chapter IV above, System 2 Type Thinkingis easily disrupted if the brain becomes distracted, tired, or overloaded.[35]

Because of its limitations, the System 2 brain is inherently lazy and will not automatically engage – even when logic is obviously called for – if System 1 thinks it has the situation under control. When its guard is down, as a result, System 1 has free rein, and this can lead to errors of judgment and flawed decision-making. In that context often examples of apparently simple math problems are being named: If it takes 5 carpenters 5 hours to make 5 wooden boxes, how long will it take 100 carpenters to make 100 boxes? Its implied simplicity triggers the System 1 brain to answer intuitively with 100 hours before System 2 has even been alerted, and the correct answer (5 hours) is missed. Had the puzzle appeared more complicated at the outset, the likelihood of System 2 becoming involved would have been much greater.[36]

Only when the data doesn’t fit compared to known information already stored in the brain (System 1), we are forced to engage the prefrontal cortex (System 2) to perform a rational comparison of new to old information and to pursue connections between thoughts and actions in line with internal goals. In other words, it requires effort to form new connections and consequently learn something new. Unsurprisingly then, lasting change (for example in perspective or habits) takes effort and requires substantial brain activity before it is “hardwired”. Everything we think and do to manifest these new connections means continually finetuning such new behavior.[37]

The brain is also wired to recognize so-called “environmental errors” – perceived differences between an expected outcome and the actual outcome. When the brain perceives a contradiction, intense neural firing takes place in an area of the brain connected to the fear center. This, in turn, engages the fear circuitry of the brain and can start an anger or fear response that is highly counterproductive to any change process.[38]

The theory proposes that through consistent performance, a new behavior can become habitual so that it is initiated automatically upon encountering cues via the activation of learned context associations. Habitual behaviors are considered to be self-sustaining; so, a behavior change can lead to the long-term formation of new habits and a shift in perspective. New habit formation should include techniques that support the motivation and control needed to repeat a certain action to use the value of repetition on habit development. It was found for example that fifteen interventions helped people adopting health-promoting behavior.[39]

How Does this Relate to Coaching?

In coaching one person (the coach) supports another person or group (the client(s))in generating new thinking and insight for them to create learning and new behaviors, often to generate a shift in certain perspectives and/or change in habits that don’t serve them (anymore). As a result, the client(s) can break out of their deeply hardwired autopilot our brains favor and move into more conscious thought and deliberate action, embedding new and positive habits to achieve long-lasting change. So, in this coaching process, it is the client(s) who free themselves from their own impasses and generate new connections for themselves. These connections are energizing to the brain and the coach can support the client(s) to harness this energy and motivation to move to action. Coaching can hereby make use of the brain’s preference for hardwiring. It deepens connections around insights and embeds learning on the way to establishing new habits. This is of great benefit to the client(s), as the brains hardwiring is more dependable and better able to deliver results than our conscious brain. Meaning, once a new behavior has been repeated several times, it gets hardwired and is triggered automatically and unconsciously. A new habit has formed.[40]

The following is a list of possible tools that a coach can use to support their clients in the process of changing a perspective or creating new habits:[41]

- Listen actively – Being fully present and listening for the whole of the person, not only what they say but also how they say things, choice and tone of words, gestures, and expressions

- Ask powerful questions– What is your reaction when you have this thought? Who would you be without having this thought? What could be another angle to think about this? What else might be true?

- Make observations – Playing back what clients are saying about themselves

- Pause – Bringing in the distance and emotional stillness for the client (e.g. breathing exercise, count to five before answering) so that the client can respond vs react, has the chance to reflect, and then decide

- Acknowledge – See the client who they are in their uniqueness and wholeness of their being

- Let them watch themselves from the outside, like in a movie

- Use roleplay, metaphor, or analogy – What would you suggest a good friend/your child do in this situation?

- Create awareness – Challenge the client to evoke awareness and insights

- Introduce lightness and playfulness– What about this situation could be fun? What would it be costing you to / if you …?

- Use extreme perspectives– What is the worst thing / best outcome that can happen? What happens if you are fully responsible / you are not responsible at all? What opportunities open up? What alternatives lie in-between?

- Use coaching tools and techniques –g. mindfulness exercises, visualization, Enneagram, Wheel of Life, coaching power tools, DISC, etc. (careful with CBT & NLP!)

ATTENTION: Before using any kind of tools or techniques, always first check-in with the client and get their permission!

- Create action –action is doing and the opportunity to experience something new and can be critical for the clients feeling of success and achievement

- Make the client accountable – Clients are the owners of their lives and are resourceful to find their own answers and to be responsible for the same

This paper could show that the coaching approach can also be explained based on a simplified neurophysiological view and illustrates on a high-level basis what happens in the brain when we want to shift a perspective or achieve long-term changes in our behavior.

Your brain is plastic. You have the power within any age, to be better, more capable, continuously growing a progressively more interesting life. Dr. Michael Merzenich

References

[1]https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/perspective; https://dictionary.cambridge.org/de/worterbuch/englisch/perspective

[2]https://www.psychologytools.com/self-help/thoughts-in-cbt/

[3]https://oxfordre.com/psychology/

[4]https://www.verywellmind.com/what-is-brain-plasticity-2794886

[5]FM-ENS Neuroscience and Coaching - Google Docs

[6]https://www.verywellmind.com/what-is-brain-plasticity-2794886

[7]https://www.verywellmind.com/what-is-brain-plasticity-2794886

[8]https://www.verywellmind.com/what-is-brain-plasticity-2794886

[9]https://www.themantic-education.com/ibpsych/2019/09/27/synaptic-pruning-and-neural-networks/

[10]https://www.verywellmind.com/what-is-brain-plasticity-2794886

[11]https://www.themantic-education.com/ibpsych/2019/09/27/synaptic-pruning-and-neural-networks/

[12]https://www.verywellmind.com/what-is-brain-plasticity-2794886

[13]https://www.physio-pedia.com/Basal_Ganglia

[14]https://www.physio-pedia.com/Basal_Ganglia

[15]https://emergenetics.com/blog/neuroscience-of-change/

[16]https://www.thescienceofpsychotherapy.com/prefrontal-cortex/

[17]https://emergenetics.com/blog/neuroscience-of-change/

[18]FM-ENS Neuroscience and Coaching - Google Docs

[19]https://oxfordre.com/psychology/view/10.1093/

[20]FM-ENS Neuroscience and Coaching - Google Docs

[21]https://www.research-live.com/article/opinion/new-frontiers-reestablishing-system1system-2-truths/id/5057422#_ftn2

[22]https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dual_process_theory

[23]https://www.research-live.com/article/opinion/new-frontiers-reestablishing-system1system-2-truths/id/5057422#_ftn2

[24]https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dual_process_theory; Kahneman, D. "A perspective on judgment and choice". American Psychologist. 58 (9): 697–720. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.186.3636. doi:10.1037/0003-066x.58.9.697. PMID 14584987

[25]https://www.greenbook.org/mr/market-research-news/lessons-from-thinking-fast-slow-system-1-and-system-2/

[26]New frontiers: re-establishing System1/System 2 truths | Opinion | Research Live (research-live.com)

[27]https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mesolimbic_pathway

[28]New frontiers: re-establishing System1/System 2 truths | Opinion | Research Live (research-live.com)

[29]https://www.brandspeak.co.uk/blog/articles/system-1-versus-system-2-start-your-brand-thinking-the-way-your-customers-think/

[30]New frontiers: re-establishing System1/System 2 truths | Opinion | Research Live (research-live.com)

[31]https://www.brandspeak.co.uk/blog/articles/system-1-versus-system-2-start-your-brand-thinking-the-way-your-customers-think/

[32]https://www.greenbook.org/mr/market-research-news/lessons-from-thinking-fast-slow-system-1-and-system-2/

[33]New frontiers: re-establishing System1/System 2 truths | Opinion | Research Live (research-live.com)

[34]https://www.brandspeak.co.uk/blog/articles/system-1-versus-system-2-start-your-brand-thinking-the-way-your-customers-think/

[35]https://www.brandspeak.co.uk/blog/articles/system-1-versus-system-2-start-your-brand-thinking-the-way-your-customers-think/

[36]https://www.brandspeak.co.uk/blog/articles/system-1-versus-system-2-start-your-brand-thinking-the-way-your-customers-think/

[37]FM-ENS Neuroscience and Coaching - Google Docs / https://emergenetics.com/blog/neuroscience-of-change/

[38]https://emergenetics.com/blog/neuroscience-of-change/

[39]https://oxfordre.com/psychology/view/10.1093/

[40]https://www.danbeverly.com/brain-based-coaching/#ch-10

[41]ICA_Power Tool – Perspective vs Heaviness_AK

https://www.pinterest.ch/pin/4222193387881995/

Kahneman Daniel, Thinking, Fast and Slow, 4. Siedler Verlag München