Research Paper By Nathalie Mollah

(Expat Life Coach, THAILAND)

Introduction

Expatriation. Such a simple word for such an amazing and surprising experience. Leaving the comfort zone, routine, landmarks behind in order to experience a new life, often far from the loved ones; facing cultural shocks, having some difficulties with the barrier language, trying to adapt to the new environment… All these phases will require time, perseverance, personal awareness and a strong self tolerance.

Living in a new environment and culture in a host country is definitely a challenging experience. Not only new expatriates who start a new mission face different stages of adaptation; those mastering the expatriation will also experience some drastic changes if compare to their last experience.

An overseas assignment is a change which requires the expatriates, their spouses and children to restructure, develop and adapt in response to the requirements of the new environment.

This research paper will concentrate first on understanding the importance of culture, then on the different phases of the expatriates’ adaptation during expatriation, and will end with a chapter on how coaching would help to this process of adaptation.

Part 1: The importance of the culture

Culture

Culture is the software of the mind Hofstede

Hofstede described in 1991 the culture as “the collective mental programming distinguishing people in one group from people in other groups”. In this sense, culture is a system of meanings, values and beliefs, expectations and goals. Later, Punnet in 1998, will define it as:

- Culture is learned. This means that it is not innate; people are socialized from childhood to learn the rules and norms of their culture. It also means that when one goes to another culture, it is possible to learn the rules of a new culture.

- Culture is shared. This means that the focus is on those things that are shared by members of particular group rather than on individual differences.

- Culture is compelling. This means that specific behavior is determined by culture without individuals being aware of the influence of their culture, as such; it means that it is important to understand culture in order to understand behavior.

- Culture is interrelated. This means that although various facets of culture can be examined in isolation, they should be understood in context of the whole; as such, it means that a culture needs to be studied as a complete entity.

- Culture provides orientation to people. This means that a particular cultural group tends to react in the same way to a given stimulus; as such, it means that understanding a culture can help in determining how group members might react in various situations.

Acculturation

Acculturation is the process by which group members from one cultural background adapt to the culture of a different group Rieger

The culture in which we are raised deeply affects our behavior and thinking. Going from another culture to another will lead to a process of acculturation. Webster, in 1996 defined the acculturation period as “ the modification of cultural traits induced by contacts between people having different ways of life or in short, cultural change.”

Berry and Kailin, in 1995, explained that four basic orientations to cultural relations are possible in the acculturation process:

- The Integration : Attraction to partner’s culture and preservation of own norms.

- The Assimilation : Attraction to partner’s culture but non preservation of own norms.

- The Separation/Segregation : Preservation of own cultural norms but non attraction to partner’s culture.

- The Marginalization: Non preservation of own norms and non attraction to partner’s culture.

In the expatriation, we understand that integration is the most optimal form of interaction. Indeed the expatriate integrates himself into the other culture and at the same time he remains loyal to his own culture; while marginalization is the most dysfunctional mode.

If expatriates preserve their own cultures and are not attracted to the local’s cultures, they will probably experience difficulties in adjusting to the new environment in the host country. Same scenario will happen if they retain their own cultures and they do not want to accept a foreign culture, even though they are temporarily part of that culture.

Intercultural dimension

Crossing Cultures

Understanding the culture of the host country will help the expatriate to make this mission a success. Nevertheless, understanding a culture is a general problem about understanding the life experience of others. This process links the ‘internal life’ (based on the culture and experience) and the ‘external life’ ( in this case the new environment in the host country) of a person.

Researchers developed frameworks for cross-cultural communication. One of the most famous is Hofstede’s cultural dimension theory. Hofstede described the effects of a society’s culture on the values of its members and how these values relate to behavior.

His theory proposed six dimensions along which cultural values could be analyzed and compared between countries.

- Power distance: strength of social hierarchy

- Individualism vs collectivism: degree to which individuals are integrated in a group

- Masculinity vs. femininity: task orientation vs. person-orientation.

- Uncertainty avoidance : a society’s tolerance for uncertainty and ambiguity

- Long Term Orientation: degree to which a society embraces, or does not embrace, long term devotion to traditional, forward thinking value

- Indulgence vs Restraint: degree of self gratitude and life enjoyment.

His work established a major research tradition in cross-cultural psychology and has been used by researchers and consultants in many fields relating to international business and communication. It continues to be a major in cross-cultural fields in order to understand other aspects of culture such as social beliefs.

Conclusion

Knowing their own culture is vital for the expatriates to smoothly accept the process of acculturation.

Besides, in order for this process to be a success, it is important for them to understand the different cultural dimensions of their host countries.

Nevertheless, even though they will successfully analyze and reflect on their “new” home’s cultural aspects, adapting in this “new” environment will take time and energy.

The second part will describe the different phases of adapting abroad.

Part 2: The adaptation process

The degree of psychological and socio-cultural comfort with various aspects of a host country Black, 1988.

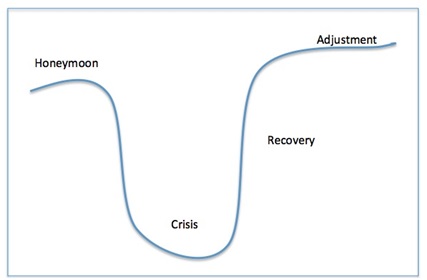

Adapting to a new environment takes time and the pace of transition varies from person to person. The typical pattern of cultural adjustment often consists of distinct phases as Lysgaard developed, in 1955, in his U-Curve model of adjustment such as:

Phase 1. The Honeymoon Stage

Phase 2. The Crisis : Culture Shock

Phase 3. The Recovery and Understanding

Phase 4. The Adjustment

Adjustment as a process over time seems to follow a U-shaped curve: adjustment is felt to be easy and successful to begin with; then follows a ‘crisis’ in which one feels less well adjusted, somewhat lonely and unhappy; finally one begins to feel better adjusted again, becoming more integrated into the foreign community. Lysgaard

Phase 1: The Honeymoon Phase

Everything is exciting, new, and predominantly positive

This phase is best described by feelings of excitement, optimism and wonder often experienced when you enter into a new environment or culture. While differences are observed, expatriates are more likely to focus on the positive aspects of the new environment.

This phase is also known as Euphoria stage which usually starts during the first week in the host country.

Phase 2: The Crisis Phase

Unsure of customs, overwhelmed, anxious, confused, irritable, hostile

This what is often termed as “culture shock.” Culture shock has been defined in different ways by many social scientists. In general, it is a term used to describe the anxiety and feelings (of surprise, disorientation, confusion, etc.) felt when people have to operate within an entirely different cultural or social environment. It grows out of the difficulties in assimilating to the new culture, causing difficulty in knowing what is appropriate and what is not. Often, this is combined with strong disgust (morally or aesthetically) about certain aspects of the new or different culture. Culture shock does not necessarily occur suddenly, but may gradually begin to affect a person’s moods over time. The length of time a person experiences culture shock depends on how long they stay in the new environment, as well as their level of self-awareness.

Culture shock manifests itself in different forms with different people but some symptoms can be:

Phase 3: The Recovery and Understanding Phase

Flexible, open to new experiences, better understanding of host environment, developing social network.

It is a stage where people start understanding the culture, environment and tries to adopt host country culture, norms, values start communicating with local people.

Recovering from culture shock is handled differently by everyone. We each have our unique circumstances, background, strengths and weaknesses that need to be taken into consideration.

Phase 4: The Adjustment Phase

Able to maintain home cultural practices, beliefs accept or incorporate new cultural practices, beliefs.

The stage where people become master in the culture and stable in new environment.

With time and patience, we can experience positive effects of cultural adjustment, like increasing self-confidence, improved self-motivation and cultural sensitivity. As you gradually begin to feel more comfortable in and adjusting to the new environment, you will feel more like expanding your social networks and exploring new ideas. You will feel increasingly flexible and objective about your experience, learning to accept and perhaps practice parts of the new culture, while holding onto your own cultural traditions.

Conclusion

Accepting the adjustment process through this model is tempting, as it makes the process predictable and the symptoms recognizable. However, is there always a “honeymoon phase”? Should we consider this adjustment cycle to apply universally? Do all expatriates undergo the same stages in the same order? Or is it possible that some of the stages reoccur?

Reiche, in 2011 developed in an article that “So far there is no clear-cut evidence and the results of research overviews (e.g. Black and Mendenhall, 1991; Bhaskar-Shrinivas et al., 2005) suggest that it is impossible to either fully accept or reject the U-shaped model of adjustment. Thus, not everyone may experience all the stages, not everyone may experience them in the same order, and not everyone may experience them only once.”

In other words, each expatriate may experience culture shock differently, depending on their preparation, their assignment type/duration, as well as their vulnerability to culture shocks.

Also, if this process is not universal, how could expatriates prepare themselves individually to cope this emotional and psychological shock? How could they adjust to their new culture more efficiently?

Part 3: Adapting with the Coaching

Enriched with coaching, intercultural professionals will be better equipped to fulfill their commitment to extend people’s world views, bridge cultural gaps, and enable successful work across cultures. Rosinski

It is clear that an expatriation may bring a block or in other words emotional responses such as for example:

To release those feelings that affect the clarity of the vision and ultimately the achievement, sometimes people have to explore things that are not necessarily at the forefront of their minds. Often, they do not see that they have a block but just feel ambivalent by the goal.

The coach will encourage expatriates to observe and become aware of their own way of interacting. Once they are self-aware, they will be asked to compare their chosen way of interacting with another behavioral model, to see what other possibilities might exit.

The coaching conversations can help to resolve, reconcile and establish a new path as the coach assists the coachee to explore his or her story. By using specific coaching tools, coaches will allow their expatriate coachees to find the block naturally and prepare them to avoid or cope more efficiently the “crisis phase” and its cultural shocks.