Research Paper By Matthew Francis

(High-Performance Coach – Business Executives and Athletes, SOUTH AFRICA)

Introduction

Introduction

We’ve all seen it before, the tennis player losing the point and smashing their racquet. Or the basketball player who, after missing the hoop, throws the ball into the crowd. Or, how about that well-known YouTube clip where the office worker throws the computer monitor out of the cubical?

It is that part of the game or our lives that we often refer to as the mental game. It is that area where we are aware of or, understand ourselves about our surroundings. Roughly speaking, this referred to as emotional intelligence (EI).

Author Travis Bradberry writes, “EI is so critical to success that it accounts for 58% of performance in all types of jobs.” (Bradbury and Greaves 2009:20) Gilbert Enoka, the mental conditioning coach for arguably the greatest sports team of all time, the All Blacks rugby team from New Zealand, is convinced that mastering these mental skills is most certainly the “final frontier” for professional sports. (Bills 2018:384)

Amongst others (Hanin, Laborde, Dosseville, Allen, Meyer, Fletcher), Kopp and Jekauc Point out that there is much consensus within the world of sports psychology that EI plays a key role in sports performance. (Kopp and Jekauc 2018: no page number)

This paper explores the relationship between performance and EI. It will describe the nature of EI and highlight the importance of EI for high performing sports teams and athletes. The key area this paper attempts to explore is how the mental conditioning coach (MC) can coach athletes and teams in the area of EI thus helping the above to perform at their optimum.

-

What is Emotional Intelligence?

It was Michael Beldoch who, in 1964, first coined the term “emotional intelligence” and Daniel Goleman who popularized the term in his book, “Emotional Intelligence – Why it can matter more than IQ .” (Chowdhury 2020).

Several definitions of EI have been suggested. Here are but a few;

Travis Bradberry offers his definition of EI as, the “ability to recognize and understand emotions in yourself and others, and your ability to use this awareness to manage your behavior and relationships.” (Bradberry and Greaves 2009:17) Ramsay adds, “… emotional intelligence can be defined as one’s ability to observe, detect, and categorize one’s own emotions as well as those of others, while using this information to inform one’s decisions, thinking, and behavior….” (Doug Ramsay 2017)

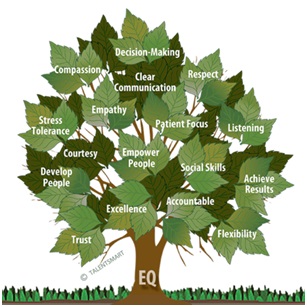

Daniel Goleman’s work illustrates the skills often associated with an emotionally intelligent person (See Appendix: 1)

In their work, Bradberry and Greaves describe their list using the metaphor of a tree to show how these skills can be grown. Unlike IQ and personality, the pair reminds the reader that EI can be developed:

Figure 1: EI as a foundation for a host of critical skill that can grow over time. (Bradberry and Greaves 2009:20)

Figure 1: EI as a foundation for a host of critical skill that can grow over time. (Bradberry and Greaves 2009:20)

When one considers the skills above, such as – decision making, accountability, results in achievement, stress tolerance, trust, the ability to control thoughts and feelings, the ability to relate to the emotions of others, and the ability to forget and move on rationally, one can clearly see how EI can impact the performance of those involved in sports at a high level.

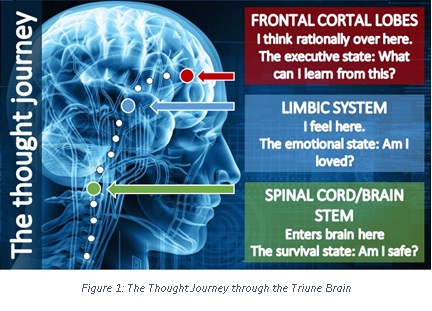

EI then is the ability to process one’s perceptions and respond in a logical mature fashion. To understand this concept further, a basic understanding of how the brain deals with perception and response (The Thought Journey) is helpful.

The neuroscientist, Paul Maclean’s “Triune brain theory” proposes that the human brain is made of three interconnected brains or thought centres.

Ernest Semerda, explains the theory:

As we perceive our world through our senses, our perceptions journey to the brain through the spinal cord.

As we perceive our world through our senses, our perceptions journey to the brain through the spinal cord.

Our perceptions first encounter our Reptilian or Primitive brain, according to McLean. The Primitive brain deals with the survival state its primary question is, “Am I safe?” Accordingly, it is this part of the brain that deals with the fight, flight and freeze responses. Secondly, our perceptions pass through the Limbic system. The limbic system is the emotional seat of the brain. It is impulsive and powerful. Its primary question is, “Am I loved?”Lastly, our thoughts and perceptions reach the Frontal Cortical Lobes, the Neocortex, known as the rational brain. This region of the brain is responsible for learning, creativity, logic, reasoning and thinking. Once an appropriate response has been formulated by the brain, it is then sent back through the same pathways for action. (Smerda 2013)

Bradberry and Greaves point out the implication of this journey – one “experiences things emotionally before one’s reason can kick into gear”. (Bradberry and Greaves 2009:17) People who have high EI can regulate these emotionally charged reactions from the Limbic System and are accordingly able to respond in more rational and stable ways.

The Two Primary Competencies of EI- Personal and Social

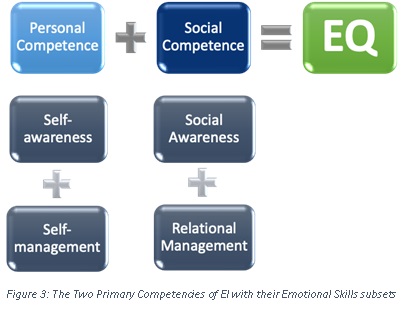

Bradberry and Greaves neatly summarize four skills that together makeup EI. These four emotional skills pair up to form a subset under two primary competencies – Personal competencies and Social Competencies, illustrated below. Each subset includes an element of awareness and another of management. (Bradberry and Greaves 2009:23-24)

EI = Personal Competency + Social Competency

The subset of Personal competencies – self-awareness and self-management.

Self-awareness

Self-awareness, Bradberry and Greaves say, is the “ability to accurately perceive one’s emotions at the moment and understand one’s tendencies across situations.” (Bradberry and Greaves 2009:23-24) For the athlete, this may be the awareness of fears, doubts, dreams, self-talk, or expectations from self.

Self-management

Self-management is the “ability to use one’s awareness of one’s emotions to stay flexible and direct one’s behavior positively. This involves managing one’s emotional reactions to situations and people.” (Bradberry and Greaves 2009:32) Athletes developing self-management must learn to regulate their feelings of disappointments and nervousness or negative self-talk, etc.

The subset of Social competencies – social-awareness and relational management.

Social awareness

“Social awareness is the ability to accurately pick up on emotions in other people and understand what is really going on with them”. (Bradberry and Greaves 2009:32) In the sports environment, most athletes compete in teams and even if they are individual athletes, they compete against competitors. Social awareness includes perceiving the emotions of fellow team members and those of the competition.

Relational management

Bradberry and Greaves point out that relational management is often the result of mastering the first three emotional skills: Self-awareness, self-management, and social awareness. it is they say, “the ability to use one’s awareness of one’s own emotions and those of others to manage interactions successfully”. (Bradberry and Greaves 2009:44) Relational management for the athlete would include developing a habit of constructive team talk or the skill of presenting confidence in the face of competition.

The importance of emotional intelligence for high performing sports teams and athletes

When one considers the skills outline by Goleman, Bradberry, and Greaves, above, (such as – decision making, accountability, results in achievement, stress tolerance, trust, the ability to control thoughts and feelings, the ability to relate to the emotions of others and the ability to forget and move on rationally) in comparison to the two Primary competencies of EI, one can clearly see how EI can impact the performance of those involved in sports at a high level.

World renown Performance Coach, Timothy Gallwey, explains how for high performing individuals – be they high performing athletes, sports teams, or business executives -:

Performance = Potential – Interference (W.T. Gallwey 2001)

According to Gallwey, personal performance is, therefore, directly related to the potential where potential is the trained ability and experience to reach a goal. Potential, however, does not ignore challenges. Even the very best of intentions can lose momentum and still be derailed. Gallwey understands these challenges as “interferences”. For high performers, these interferences manifest as external and internal expectations, negative self-talk, unexpected setbacks, and barriers. (Francis 2020:1) To overcome the interference in the Equation, the athlete will need to develop a keen sense of self-awareness, self-management, social awareness & relational management – Emotional Intelligence.

The research of Galarraga, Cecchini, Luis-de-Cos, Saies, and Luis-de-Cos, indicates that as the EI of elite canoeists increased, so too did their overall medal count and personal time commitment to the sport. (Galarraga, Cecchini, Luis-de-Cos, Saies and Luis-de-Cos 2019:6-7) This finding is supported by Kopp and Jekauc, who show how EI contributes to ongoing motivation to the intense training needed for high performance. (Kopp and Jekauc 2018)

Top athletes must be aware of and be able to regulate their emotions. In the heat of the moment, the athlete can easily change lanes from a “resourceful state of consciousness” to an “unresourceful state.” (Kerr 2013:104) Instincts of survival kick in, the thoughts led by the primitive brain. Athletes become heated, overwhelmed, and tense. The All Blacks call this “Red Head”. This is contrasted with having a “Blue Head”, where athletes can consider alternatives, understand consequences, and remain focused on the task at hand. (Kerr 2013:105)

Additionally, “competitive sport is fundamentally a social activity. Teamwork, team role, responsibility, leadership, mutual goal-setting, problem-solving, cooperation, communication, and respect for others, etc. are challenges that are influenced by emotions”, explains Kopp and Jekauc. (Kopp and Jekauc 2018)

The place for the mental conditioning coach in coaching high performing sports teams and athletes in emotional intelligence

So important is the role of the Mental Conditioning Coach (MC) that Sir Graham Henry, former All Blacks coach, refers to their team’s MC as “the backbone of the whole thing”. (Bills 2018:283)

The acceptance of the MC and the relationship between EI and performance provides sports teams with a unique opportunity to add another weapon to their arsenal for performance. MC’s cannot underplay the value of EI development. So, where to from here? Below are some suggestions:

- Assessments can be used to formulate a baseline. (Appendix 2)

- MC’s should begin their work with the Senior Team Coach. Studies show coaches with high EI develop higher-performing athletes. (Kopp and Jekauc 2018)

- Group/team coaching. The goal is to grow the culture of the team and lead the team to understand each other and trust each other. Ideas relating to team vision and behaviors like constructive team talk can be discussed and implemented.

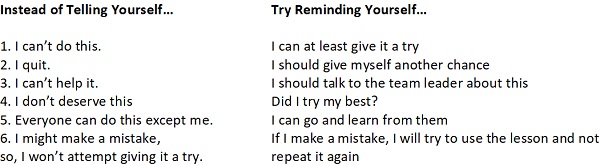

- Individual coaching. Athletes can be coached by the MC to understand their emotions and to develop applicable coping strategies to regulate those interfering with performance. Negative self-talk can be an overwhelming battle in the face of competition. Not only does the athlete compete against their opponent, but they then also have to compete against themselves. MC’s can help athletes to combat negative self-talk by replacing it with instructional self-talk.

- The MC can employ EI exercises to help the team or athlete develop their EI. (Appendix 3)

Conclusion

“58% of performance”. (Bradbury and Greaves 2009:20) The “final frontier” for professional sports. (Bills 2018:384) Underestimating the mental game in sports is irrational. Within the mental game, EI is arguably the greatest weapon an athlete can develop. The development of EI is associated with the decrease of interferences, overall achievement, personal time commitment to the sport, motivation to train, maintaining a “Blue Head” in the competition, and the growth of teamwork.

It is clear that MC’s can play a key role as members of the coaching staff by assisting in the development of EI within the team and individual athletes, thus directly contributing to the performance of the above.

Reference list

Beldoch M. and Davitz J.R. 1964 The Communication of Emotional Meaning. McGraw-Hill: New York

Bills P. 2018 The Jersey: The secrets behind the world’s most successful sports team. Macmillan: London

Bradbury T. and Greaves J. 2009 Emotional Intelligence 2.0 TalentSmart: San Diego

Chowdhury M.R. 2020 How to improve Emotional Intelligence through training 01 September 2020

Online: https://positivepsychology.com/emotional-intelligence-training/

Accessed: 12 November 2020

Francis M.J. 2020 PERFORM High-Performance Coaching Model 21 October 2020

Online: https://forum.icacoach.com/discussion/148184/perform-high-performance-coaching-model#latest

Accessed: 14 November 2020

Galarraga S., Cecchini J., Luis-de-Cos I. Saies E., Luis-de-Cos G. 2019 Influence of emotional intelligence on sport performance in elite canoeist. Journal of Human Sport and Exercise. vol 15, issue 4, page 1-11 Online: doi:https://doi.org/10.14198/jhse.2020.154.05

Accessed: 15 September 2020

Gallwey W.T. 2001 The Inner Game of Work: Focus, Learning, Pleasure, and Mobility in the Workplace. Random House: New York

Hanin Y.L. Emotions in sport: Current issues and perspectives. In: Tenenbaum G., Eklund R.C., (editors) 2012 Handbook of Sport Psychology. John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken

Kerr J. 2013 Legacy: What the All Blacks can teach us about the business of life. Constable: London

Kopp, A. and Jekauc, D. 2018The Influence of Emotional Intelligence on Performance in Competitive Sports: A Meta-Analytical Investigation. Sports 2018, vol 6, issue 4, number 175

Online: https://doi.org/10.3390/sports6040175

Accessed 10 November 2020

Laborde S., Dosseville F., Allen M.S. Emotional intelligence in sport and exercise: A systematic review. Scandinavian journal of medicine & science in sports. 2016 vol 26 pp.862–874.

Online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26104015/

Accessed: 9 November 2020

Laborde S. Bridging the Gap between Emotion and Cognition. In: Raab M., Lobinger B., Hoffmann S., Pizzera A., Laborde S. (editors) 2016 Performance Psychology. Elsevier GmbH: München

Meyer B.B., Fletcher T.B. Emotional intelligence: A theoretical overview and implications for research and professional practice in sport psychology. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology. 2007 vol 19 pp.1–15. Online: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/10413200601102904

Accessed: 10 November 2020

Ramsay D. 2017 Emotional Intelligence: A History and Definition 2 February 2017

Online: https://www.adventureassoc.com/emotional-intelligence-a-history-and-definition/

Accessed 14 November 2020

Semerda E.W. 2013 EI: Emotional Intelligence, 3 Brain Theory & Leadership 19 December 2013

Online:

Accessed: 14 November 2020

Appendix 1

Daniel Goleman’s skills are often associated with emotionally intelligent people. (Chowdhury 2020)

Appendix 2

17 Emotional Intelligence Tests and Assessments

https://positivepsychology.com/emotional-intelligence-tests/

Appendix 3

Tips for Enhancing Your Own Emotional Intelligence:

- Reflect on your own emotions;

- Be observant (of your own emotions);

- Use “the pause” (e.g., taking a moment to think before speaking);

- Explore the “why” (bridge the gap by taking someone else’s perspective);

- When criticized, don’t take offense. Instead, ask: What can I learn?