Our maps of reality

One of the most important aspects of human thought has been the quest to distinguish between external events, such as changes in our environment, and internal events, such as perceptions, and thus to differentiate between objective and subjective. 2 Our mind cannot, however, “cut” a piece of reality and apprehend it, save it in the memory or reproduce it in its entirety. Our senses, perception, frame of reference, selectivity of attention, memory, language, they all have first a big “bite” of that piece of reality before saving it, integrating it, or communicating it. Unless we use special spirituality techniques, immediate access to reality and truth is blocked by the medium of acquiring the information. Virtual reality is the proof of how easily our mind can be fooled, into accepting as real what is only perceived.

Our reality is a perception. We perceive the external environment based on our sensorial experiences, and create a map of reality in our head. The very same mental representations that are used to filter, give meaning and interpret the actual world are used in interpreting virtual realities. VRs are recognizable by users through real-world metaphors, and they appeal to the already existent map of reality in our head. When moving your hand with a wired glove in a VR, you are mapping the dimensions of the virtual world into your internal perception-structuring system.

Our sense of physical reality is a construction derived from the symbolic, geometric, and dynamic information directly presented to our senses. Accurate perception involves considerable a priori knowledge about the possible structure of the world. If we see a number of pictures with parts of some objects present in our world, our previous knowledge will complete the sensory input and we will accurately interpret those objects to continue to exist in their entirety.

A large part of our sense of physical reality is a consequence of internal processing rather than being something that is developed only from the immediate sensory information we receive. Our sensory and cognitive interpretive systems are predisposed to process incoming information in ways that normally result in correct interpretation of the external environment, but sometimes they resonate with specific patterns of input. If the display technology offers high perceptual fidelity, the same constructive processes will be triggered by virtual environments.

If veridical sensory cues can reshape the boundaries of reality, if pre-existent frames of reference filter and interpret sensory information, and if our memory only remembers what it considers as important, we can ask ourselves how “real” is what we perceive as actual reality?

What do VRs have to teach us about how the human brain creates the map of reality?

How could you increase client awareness regarding the role of perception in the creation of “reality” in our head?

Perception is an active and selective process

Interestingly enough, as Jaron Lanier (1992) has stated, VRs suggest that we shouldn’t consider eyes as “cameras“ that passively take in a scene… but as a kind of spy submarines moving around in space, gathering information.

The perspective of ecological psychology, which offers an influential theoretical foundation for virtual reality (J.J. Gibson, 1986) emphasizes this view6. The direct perception of the environment allows individuals to search for “affordances” in the environment. Affordances help us understand how to interact with an object and are the basis of action. For example, a handle helps us understand that a cup affords being picked up. Affordances provide strong clues to the operations of things. Affordance recognition must be understood as a contextually sensitive activity for

determining what will (most likely) be paid attention to and whether an affordance will be perceived. Gibson does not view the different senses only as producers of visual, auditory, tactile, or other sensations, but as active seeking mechanisms for looking, listening, touching, etc. This suggests that we seek in the environment and select clues and information that are considered as meaningful, interesting and valuable for us, from the viewpoint of developed scenarios. The information perceived will than confirm a scenario previously conceived in our head. By observing one’s own capacity for visual, manipulative, and locomotor interaction with environments and objects, one perceives the meanings and the utility of environments and objects, i.e., their affordances.

How can you make the client think outside the box and perceive reality with a different perspective, which does not necessarily confirm his/her scenario?

Immersive VR: CAVE

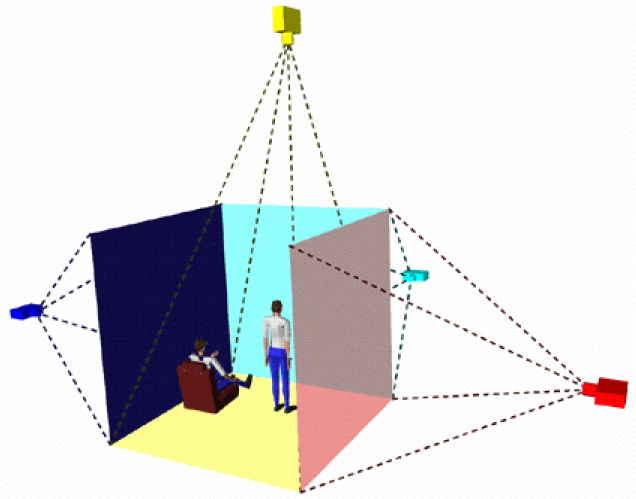

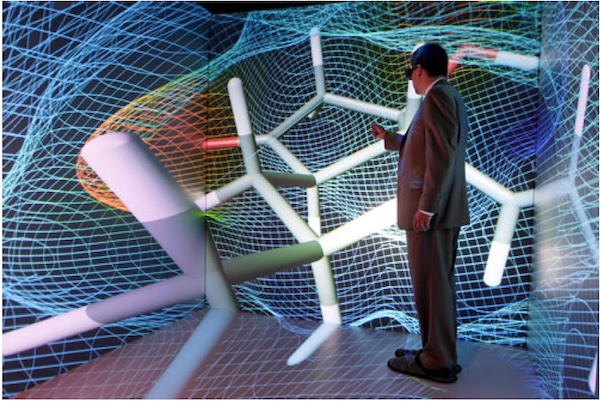

One of the primary characteristic of virtual environments is their capacity to produce immersive experiences for users/players/ viewers through technologies for producing verisimilitude and interactivity. The largest immersion is offered by CAVE, a type of virtual environment where user‘s point of view is adjusted by tracking the head and/or hand, while the user wears a location sensor and 3-D stereo glasses.

The CAVE is a Chamber World, a 3-D real-projection theater made up of three walls and a floor and first developed at the Electronic Visualization Laboratory at the University of Illinois. The CAVE provides a first-person experience. As a CAVE viewer moves within the display boundaries, the correct perspective and stereo projections of the environment are updated and the image moves with and surrounds the viewer.

The active function of perception, the search for “affordances” is very clear in CAVE systems, as the situational awareness is constructed on three levels: