Research Paper By Maria Tsoutsani

Research Paper By Maria Tsoutsani

(Health & Wellness Coach, GREECE)

Health is an intrinsic goal, yet it is often compromised by habits and lifestyles. Behaviors such as using tobacco, eating unhealthy foods, and failing to exercise can greatly enhance morbidity and mortality. Also, poor adherence to health care interventions and prescriptions compromises health outcomes. Motivation thus plays a critical role both in healthy living and in enhancing treatment adherence.

The decision to stop health-compromising behaviors, such as smoking cigarettes, abusing alcohol and overeating unhealthy foods, or starting healthier behaviors, such as exercising regularly or reliably following a medication regimen, requires patients to be motivated, and SDT proposes that the most effective change requires not just any motivation but, specifically, autonomous motivation (not controlling motivation).

Let’s get to the heart of what SDT is all about, which is this question, what is motivation? We can be motivated into action by an extrinsic stimulus like external pressure or forced to do something or be rewarded, we can also be motivated into action by intrinsic forces like internal values or a real curiosity or passion or desire to do something. In the old days, we were really focused on how to control people from the outside using reinforcement and rewards and punishments (extrinsic motivation) but today, the questions in motivation are really more about, why do people make the choices they make and how can we sustain them on the pathways that they choose to act in? And, as we look at those issues, we see just how important Volitional Behavior is, how important it is when people do things willingly (intrinsic motivation). And in SDT, again, we really identify two forms of this volitional behavior, one is Intrinsic motivation, the doing things out of interest and enjoyment, and then secondly, Internalized motivation, doing things out of value and because you understand the worth of that particular action (integration motivation). And we’re really focusing SDT on the factors and environments and what facilitates or undermines this volitional type of motivation. And when we think about those factors, we use a particular word for it, we use the term “Need” or “Basic need.” The term need means something essential to an entity’s growth, integrity, and wellness. For instance, a plant needs hydration, or water otherwise it will wilt. And similarly, as a psychological theory, SDT argues that we have some basic psychological needs which, when we get them we thrive and when we don’t get them, we’ve shown degradation in our functioning, regardless of what our conscious attitude is toward that need. We have only three basic psychological needs: the needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness. And I want to say a little bit about each of these needs and why it’s so important to volitional motivation and wellness.

The first of these needs is the need for competence, and competence is a need that everybody has to feel effective and capable in the activities that they’re engaged in life. I would say in SDT when we think about competence, we think of it as not just being able to attain an outcome but rather to experience growth, to have a sense that you’re developing skills, that you’re extending your abilities and this is what really satisfies the deep need for competence.

The second need in SDT is the need for relatedness, people to be optimally functioning and motivated in any setting, need to feel connected with and belonging in the atmosphere in which they’re in. They have to have the experience that, I matter, that I’m significant in some way in this group or this particular setting. And the sense of relatedness can be derived both from the experience of being cared for but also can be derived from the fact that I can contribute and I matter in this group because there’s something I can give back, so both give and take within social groups creates this idea of relatedness.

The third basic psychological needs are the need for Autonomy, and when we use the term autonomy, we really mean the term volition here or voluntary, because when you’re autonomous, you’re willingly doing what you’re doing and you endorse your own actions. When you’re autonomous, you typically experience a high degree of interest or value in what you’re experiencing and the opposite of autonomy is what we say is, heteronomy or feeling controlled by forces that are alien or outside of yourself. People don’t like to feel coerced, they want to feel like they’re the self-organizers of their actions. Autonomy is so important in SDT.

So from the above, we understand that there are many types of motivations but to facilitate change in people’s behavior towards a healthier lifestyle, we have to enhance intrinsic and integration motivation.

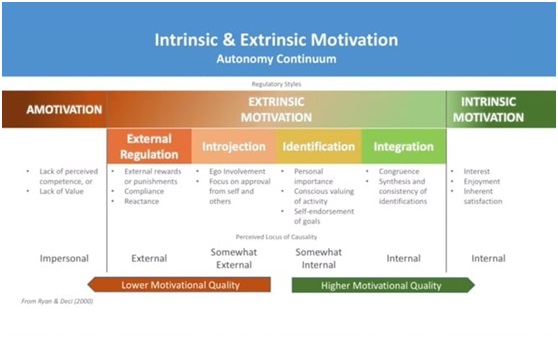

Let’s see the picture below for a better understanding of all different motivations:

I want to give some examples of both types of motivation and some of the reasons why they differ so much in their consequences and attributes. The first kind of extrinsic motivation I want to talk about is external regulation. You see it here at the left-hand side of this continuum of motivation.

External regulation is when you do something because somebody else will award you if you do the activity or will punish you if you don’t. Therefore, when you’re externally regulated the behavior is driven by external forces from without. It can be a very powerful form of motivation, if people have big enough rewards or strong enough punishments, you’ve might act very robustly to accomplish your ends. The problem with extrinsic motivation, therefore, isn’t ineffectiveness. It’s what we call its maintenance and transfer problem. This is that extrinsic motivation doesn’t last unless the rewards and punishments are right there in front of you, as soon as the rewarder or punisher walks away so does the motivation. So, again, it’s not because it’s a weak form of motivation but rather because it’s an unstable form of motivation that doesn’t last without the rewards and punishments being present.

A little bit to the right of external regulation is another form of motivation we call interjection. An interjection is also a very pressured and controlling form of motivation, but here the pressure is coming from within. So, when you’re interjecting you’re doing something because if you don’t accomplish a task or don’t do well at it you’ll feel bad about yourself or if you do well you’ll feel self-aggrandizing and proud. It’s really the pressure of self-esteem and self-approval that drives interjection. We sometimes talk about interjection in terms of ego involvement. It’s when your ego is on the line concerning doing or attaining some kind of standard at behavior. So, interjection again a very powerful form of motivation but it too is unstable. When people are highly interjected and something goes wrong, they opt to withdraw and at the same time also beat themselves up, so there are also mental health costs to interjected motivation especially when it’s pervasive. Still a third kind of extrinsic motivation.

Now, to the right of an interjection is what we call identification. Identification is when you do something because you are really identified with the worth or value of the activity. So, now you’re doing it because you’re willingly engaged in the activity. After all, you see how important the outcome might be. So, when people are identified and they’re motivated through that kind of valuing of an outcome, they tend to be very volitionally motivated and persistent. So, now we’ve gotten to the first type of stable high-quality motivation within this continuum.

Still to the right of identification is what we call integration. Integration is when you’re not only identified with the value of the activity, but that identification fits with all the other values that you have so that you can now whole-heartedly be behind the activity itself. So, as you can see that as we move from left to right we’re looking at a continuum here, that goes from very heteronomous or controlled forms of motivation like external regulation, all the way up through more on more autonomous forms of the motivation of which integration represents the most autonomous form of all extrinsic motivation. So, as you go to the right on this continuum, we’re getting more and more autonomous, and the quality of motivation tends to be higher and higher.

Now, there’s one other kind of motivation I haven’t mentioned that’s also on this diagram and it’s the one that’s way to the far left, we call it amotivation. This is the lowest form of motivation in terms of autonomy. When you’re amotivated you’re just not motivated to act either, one because you feel like you can’t do the action in other words you’re helpless, or two because you just have no value for the action at all. So, amotivation represents the least positive form of motivation on this continuum.

Paradigms of different motivations:

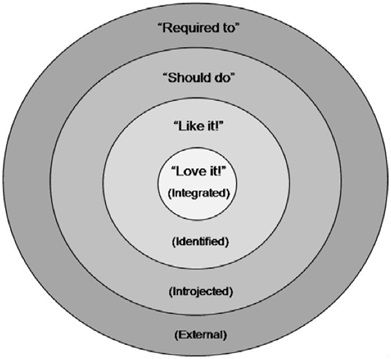

Spatial representation of different forms of extrinsic regulation. From Spence & Oades PDF (2011)

Spatial representation of different forms of extrinsic regulation. From Spence & Oades PDF (2011)

External thinking: My doctor ordered me to give up smoking

Introjected thinking “I should give up smoking,”

Identified thinking: “My doctor says giving up smoking will be good for my health.”

Integrated thinking (intrinsic) “giving up smoking will allow me to have the energy to play with my children and improve my health so that they have me around in the future.”

Every human is different. When coaching comes from an approach that is asset-focused, each individual can find personal motivation toward goal achievement.

When a doctor encourages someone to give up smoking, that person may not feel motivated because this is extrinsic motivation.

When a client thinks intrinsically about the unique benefits of giving up smoking, they are more likely to produce personal ideas for committing to that goal. For instance, the intrinsic example above. Let’s face it; most people won’t do “what’s good for them” unless it is internally motivated.

Here are a few examples of questions a health coach might utilize in a session to help clients give up smoking.

“What about giving up smoking is important to you?”

“How would giving up smoking change your life?”

“What is your ideal future?”

“What does give up smoking mean to you?

“What are your values? How do they relate to smoking?”

Depending on how the client answers, follow-up questions will continue to help that client expand. Each client is different, as is each coaching session. A coach knows that their client is the expert in their life experience.

And an example from a clinical trial for smoking cessation based on SDT

In this trial, adult participants were recruited into a study of smokers’ health. To be eligible, one needed to smoke at least five cigarettes per day and be willing to visit the clinic on four occasions over a 6-month period to discuss their health and tobacco use with health professionals and to complete questionnaires. Wanting to quit smoking was, however, not a requirement. This is noteworthy insofar as many smoking interventions only accept patients deemed ready to change or put up multiple barriers that result in only highly motivated participants actually enrolling. In this clinical trial, the goal was the opposite—to have as few barriers to entry as possible and to accept people whether they were motivated or not. In fact, on their first visit, participants were asked whether they would like to attempt to quit within the next 30 days and were accepted whether they answered the question with “yes” or “no.” More than half of the 1,000 participants said no, they had no intention to quit. The goal was to have as few barriers to entry as possible and to accept people whether they were motivated or not. The subjects were randomly assigned to either the SDT group intervention for tobacco dependence or to a community care condition. Community care patients were encouraged to discuss their tobacco use with their own physicians, were give a list of resources available in the community for dealing with tobacco dependence, and relevant printed materials.

The intervention

In the SDT intervention group, health counselors had been trained to conduct the intervention visits, although patients who at any time said that they were ready to make a quit attempt were also offered a consultation with a prescriber to discuss the use of medications for smoking cessation. During the initial sessions of the intervention, the counselors elicited participants’ histories and perspectives regarding smoking to understand the patients’ internal frames of reference. Further, counselors worked to promote participants’ reflections on what smoking provided to them and what harm it might cause them, in part so they had the relevant information with which to make a choice and in part because, if they decided to stop smoking, they would be ready to address alternative means to get the satisfactions provided by tobacco use. For example, if smoking helped them manage their anxiety, they could consider how to manage that without the use of tobacco. Additionally, counselors invited participants to consider how continuing to smoke versus stopping smoking fits with their personal values, needs, and plans for the future. Throughout treatment, counselors remained neutral concerning the treatment outcome, endorsing neither continued smoking nor stopping, and not pressuring clients toward cessation. Yet for patients ready to try stopping, the discussion then turned to enhance their perceived competence and techniques for coping with the possible barriers they might encounter. When participants made a change attempt, the focus was on their progress and on any difficulties they had had. If they tried and failed, the attempt was acknowledged, and their feelings about it were elicited. Such attempts were framed not as a failure but as learning opportunities—discovering what works and what doesn’t. The importance of personal choice regarding smoking was continuously conveyed by the counselors’ attitude and behaviors: by not pressuring or criticizing and by accepting the patients’ decisions not to try stopping without disapproving either verbally or nonverbally.

Results

As a clinical trial, the first important question concerns whether the intervention significantly impacted the key outcome, namely smoking cessation. The intention-to-treat analysis, with all participants taken into account. Analyses revealed that the quit rate in the intervention group was significantly greater than in the community care group, with an odds ratio of 2.9, indicating that nearly three times as many people quit smoking in theSDT group as in community care.

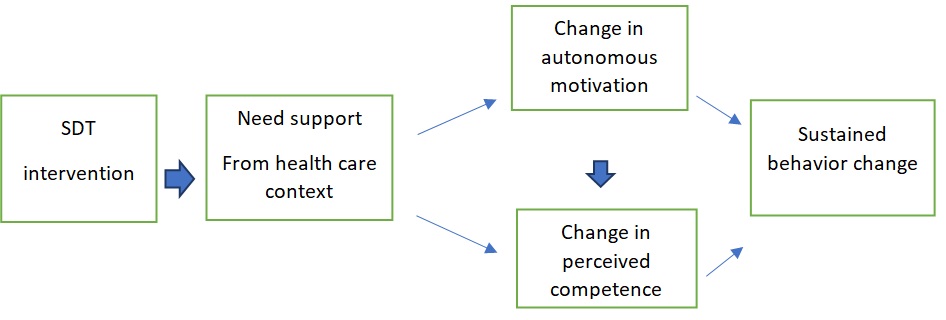

A process model of change

According to SDT, autonomy support from the treatment context should increase both autonomous motivations and perceived competence for change, which are expected in turn to be proximal antecedents of change. Within this general model, there may be specific additional variables that are affected by the intervention and that affect the health outcome. In the smoking cessation trial, we expected that taking cessation-promoting medications such as nicotine replacement would play such a role in the process model of change.

SDT also maintains that this model of change will be operative in any treatment setting, not only for treatments based on SDT principles. Thus, in the current smoking-cessation trial, we expected the model to significantly predict smoking abstinence for patients in community care, as well as for patients in the SDT intervention. Of course, we expected and found a higher level of change in the SDT-intervention group than in community care, because patients in community care on average perceived their treatment climate to be less autonomy-supportive than those in the SDT intervention group.

Accordingly, the community care participants were also lower in autonomy, perceived competence, and medication-taking than the SDT group. Multigroup structural equation modeling (SEM) was used to examine whether the data from both groups fit the SDT process model (Byrne, 2001). Results of these analyses supported the view that the SDT process model applied in both treatment situations, although, as we had previously noted, the intervention group experienced their treatment to be more autonomy-supportive, and that led to more positive treatment outcomes.

There is another finding of interest from this clinical trial. Participants also completed measures of depressive symptoms (Radloff, 1977) and vitality (Ryan & Frederick,1997) at baseline, 6, and 18 months. Analyses of the data by Niemiec, Ryan, Patrick, Deci, and Williams (2010) revealed that participants who were more autonomously motivated to stop smoking experienced greater vitality in their lives and smoked fewer cigarettes. Further, cigarette use at baseline and 6 months related positively to depressive health Care and Patient Need Satisfaction 461symptoms at baseline, 6, and 18 months and related negatively to vitality at those three times. In other words, smoking more cigarettes, which is sometimes thought to relieve depression and leave people feeling better, actually seems to do just the opposite, leaving them less vital and more depressed.

Finally, let’s see how well SDT fits with some of the ICF core competencies and how to Facilitate Autonomous Motivation and Internalization in health coaching

A health coach works with his/her clients to help them live their healthiest lives possible. At the heart of SDT is the underlying assumption that there is an inherent human need for fulfillment and self-actualization through personal growth, development, and mastery (competence), for connectedness (relatedness), and the experience of behavior as self-determined and congruent with one’s sense of self (autonomy). These three needs are considered universal and essential for well-being. Whatever supports the positive experience of competence, relatedness and autonomy promote choice, willingness and volition, interest, full engagement, enjoyment, and perceived value — the inherent qualities of intrinsic motivation. It also leads to higher quality performance, persistence, and creativity.

Coaching in support of autonomy

People need to feel they are operating their lives out of their own choice. Supporting the client’s need for autonomy is considered one of the primary tasks of a coach. The client-centered nature of coaching supports client autonomy throughout the coaching process. Coaching operates on mutual agreements between client and coach. Agendas are co-created with the client always in the lead. Health coaching is especially true as client-generated goals have more inherent “buy-in”, that is, more motivational connection. The coaching cornerstone stance that the client is “naturally creative, resourceful and whole” fosters autonomy as the coach works to evoke the inner wisdom of the client. Rather than operating from an expert point of view, the coach provides support for the client’s own decision-making, even though they assist in the process.

Coaching in support of competence

This “naturally creative, resourceful and whole” stance also supports the other key human need according to SDT, of seeking to achieve competence. Again, clients are treated as though they are indeed capable and possessing great potential. The strengths-based, positive psychology nature of coaching emphasizes acknowledging and building upon the client’s attributes and qualities they already possess. A key here is acknowledgment. Clients often minimize or fail to recognize their strengths and achievements. If their self-efficacy is already low, having been brought down by previous failure experiences, they may tend to overlook what they are accomplishing or to downplay it. The active listening skill of acknowledgment needs to be used by the coach whenever it can be genuinely utilized. As the client and coach work on self-determined goals and break them down into doable action steps, leading the client to enjoy more and more successful experiences. As they do so, they begin to feel more competent in the area of improving their lifestyle, which naturally builds their feelings of self-efficacy.

Coaching in support of relatedness

The heart of coaching is the coaching relationship itself. Creating that alliance supplies the client with a trusted resource for the support that can be relied upon unconditionally. As the coach exhibits the qualities that make up a great coaching presence, the client feels accepted, acknowledged, and cared for. Often our clients are lacking relationships in their lives where they experience adequate empathic understanding and are free from judgment.

“It is important to note that whilst a coachee may have close relationships outside coaching, s/he may not consistently feel heard, understood, valued and/or genuinely supported within those relationships. If not, they are unlikely to feel strongly and positively connected to others and in an attempt to satisfy this basic need, may attempt to connect by acting by the preferences of others, rather than one’s own.”

For the client, it is not only refreshing to relate to someone who provides unconditional positive regard and validates their experience and feelings, it may actually free the client up to explore their lives with new openness and independence. Perhaps they have been holding themselves back from making some of the lifestyle changes they need to make because of the fear of losing connection, to some degree, with others. Perhaps with the support of the coach, the client may be willing to take such risks to live more healthily.

As coaches reflect upon their work, not only with a single client but will all of the people they coach, they can benefit from asking themselves if their coaching process addresses and supports the fulfillment of these three innate psychological needs. The self-vigilant coach may want to listen to session recordings and ask themselves “Am I coaching in a way that really supports my client’s autonomy, or am I being too prescriptive or too directive? Am I using acknowledgment enough to help my client realize how their sense of competency is increasing? Am I remembering to ‘coach for connectedness’ and help my client expand their circles of support?”

If all three needs are satisfied “people will develop and function effectively and experience wellness” and if not, “…people will more likely evidence ill-being and non-optimal functioning.”

Reference

Self-Determination Theory: Basic Psychological Needs in Motivation, Development, and Wellness 1st Edition by Richard M. Ryan (Author), Edward L. Deci (Author)

https://www.coursera.org/learn/self-determination-theory

http://selfdeterminationtheory.org/

https://doi.apa.org/doiLanding?doi=10.1037%2F0278-6133.25.1.91

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9619477/