What are the facts? – Research

Research in the 20-first Gender Balance Scorecard Reports that most of the educated talent in the world and a majority of the consumer market is female. They also report a correlation between gender balance in leadership and improved corporate performance. Not surprisingly then, companies are waking up and trying to improve their gender balance.

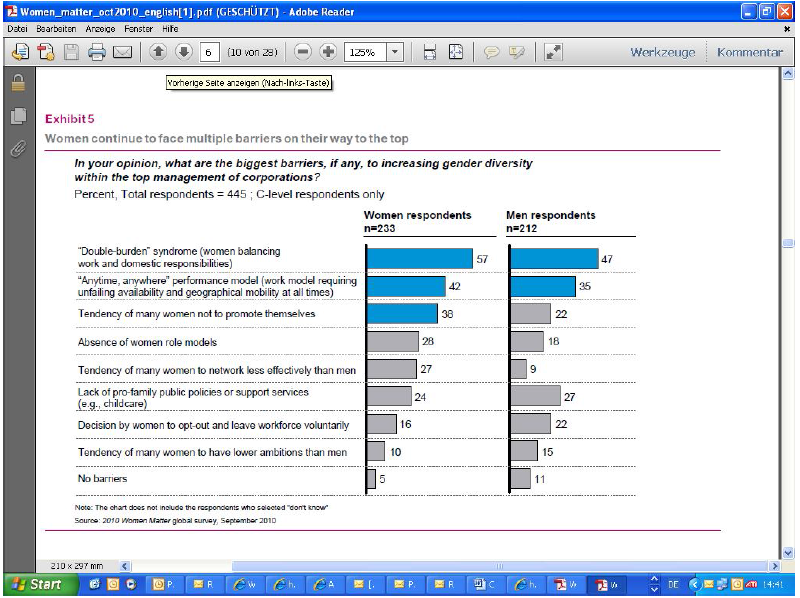

McKinsey’s 2010 Women Matter Report states that one of the reasons that change has been slow in coming are the persisting barriers women face on their way to the top. The survey of 1500 executives, across multiple industries and regions of the world, from middle managers to CEOs, identified two main barriers to gender diversity in top management.

The first one is the “double burden” syndrome – the combination of work and domestic responsibilities – which is difficult to reconcile with the second barrier:

the “anytime, anywhere” performance model.

The following exhibit from the Women Matter 2010 survey shows this impact:

Similarly, a Harvard Business Review study from ten years ago, “Executive Women and the Myth of Having it All” reported an inequity between men and women.

When it comes to career and fatherhood, high achieving men don’t have to deal with difficult trade-offs: 79% of the men I surveyed report wanting children – and 75% have them…. The disparity is particularly striking among corporate ultraachievers.

In fact, 49% of these women are childless. But a mere 19% of their male colleagues are.”

Interview results

With statistics telling us there is a difference, what do the people who are “having it all” tell us? For the purpose of this paper a number of people were interviewed.

The people were men and women with both careers and families, and therefore might be perceived as “having it all”.

Interviewees were informed about the research paper topic and the definition used by the paper of having it all to mean a fulfilling career as well as family.

Interview Questions:

- Do you consider yourself “having it all”.

- What do you believe it means?

- What are you missing out on, ie not doing or not having?

- What are others, without children, not having or doing?

- What are people without careers not having or doing?

- What do you believe are the prerequisites for having career and children, having both “it all”?

Case study 1:

Bob and Suzy – acceptability of working part-time, assumptions made about future ambition, stereotyping flexible working arrangements Bob, a computer programmer, and his wife Suzy decided ten years ago to have a family, and that each of them would ask to change their current employment to a four day week, reducing compensation proportionately. This was accepted by Suzy’s employer, a large bank, as it is common in the community and society in which they live (central Europe) for women to work part-time after having children. It was also accepted that she was now on the “mummy track” and that she had acknowledged a preference for her children over her career, and no further promotions or rewards would be considered. In her words;

they assumed I should be happy to have a part-time job and that I had no ambition to progress my career

Suzy was now performing exactly the same leadership tasks and significant responsibilities on 20% less salary, was still achieving outstanding performance appraisals, and yet promotion opportunities were closed to her.

On the other side, Bob’s application to work part-time in a large multinational insurance company, was however, rejected. In this same community, it was simply not appropriate or traditional to have men working on a part-time basis. “I insisted that I needed to be at home one day a week, and they willingly agreed that I could work from home, while still receiving my full salary. While I take phone calls and read emails, frankly my home office is more about running the kids around. But that’s what was accepted”. There was no discussion of his dedication or lack of ambition. No impact on his compensation. Bob and Suzy both agree that they are having it all per the definition given for the survey purpose, but that they definitely do not have the same lifestyle they had prechildren, and do not miss that or regret that. They believe the desire and willingness to have children changes the ability to have it all, and having both of them work does not change that or interfere further with that.

Case study 2:

Tracy and Hugh – addressing a need for workplace flexibility by ensuring childcare flexibility.

Tracy and Hugh are both Executive Directors in a bank. They have two children and both work full-time. When asked if they are “having it all” they answer yes, they have fulfilling careers but also manage to spend quality time including vacation time with their children, who are otherwise at an all day school followed by after school nanny care. When asked if there was anything they were missing out on, that perhaps others could have, they answered

yes, but it is all a choice. We choose to have the nanny take the kids on a Thursday evening so that we can have date night together, assuming one or other of us is not travelling for work. Every decision to travel has to be taken with full communication with one another and with the nanny, to ensure it is clear who is responsible for the kids at that time. The nanny has an agreed contractual number of working hours over the year. If the normal weekly hours are extended e.g due to extra hours during a day (school holidays are 13 weeks!) or in the evenings (date night) and overnight (when both travel) the extra time is compensated at a time suitable for the nanny. This requires significant planning and coordination. We are having it all, but there are three adults involved in our childcare, and each of us is actively involved and committed.

Needless to say, the nanny is a quality nanny and comes at quite a price, as does the all day international school the kids attend. Tracy and Hugh are addressing a need for workplace flexibility by ensuring childcare flexibility.