We have seen that established cultural frameworks can help understand the Japanese culture systematically. An analysis of sociocultural and managerial elements of the Japanese culture could bring a few more points into light. We could show that many aspects of the Japanese culture make it difficult for coaching as defined by ICF to be practiced without adaptation. Some cultural characteristics may demand great attention, self and cultural awareness from the coach. The work for the coach starts with acknowledging the cultural background of his or her clients to be able to establish and maintain a trust-based relationship and not get hooked by cultural differences. With Japanese clients, effective coaching may not be about self development and individual happiness. The coaching process should emphasize issues of conformity, harmony, consensus, social identity, etc. for fear that coaching results may not be grounded in authenticity.

3. Implications for coaching

Considering what we now know about the Japanese culture and how far it may alter conventional coaching styles, we will present in the following three ideas that may ensure coaching effectiveness with Japanese clients. The first one is focused on the coach himself or herself. The second one focuses the coaching process around the concept of roles. The final one focuses on relationships and systemic constellations.

3.1. Developing “Global Dexterity”

One of the duties of a good professional coach is self-management and self-awareness. A coach in Japan has to be aware of cultural backgrounds and how the coaching process may be impacted. For non-Japanese coaches, their attention may be diverted to the cultural differences and they may lose track of the coaching intent of the client.

This is where Global Dexterity (Molinsky 2013) might be useful for the coach. Molinsky defines dexterity as the “ability to adapt your behavior – smoothly and successfully – to the demands of a foreign culture without losing yourself in the process”. It starts with acknowledging cultural differences, but goes much further: it means adapting one’s behavior to conform to new cultural contexts without losing authenticity.

Using Molinsky’s model, the coach should first get some knowledge and awareness about Japanese culture and what is important for Japanese clients. Then, the coach should know his own comfort zone and use self management to be fully present for the coaching relationship. Third, using cultural and self-awareness, the coach’s behavior can be customized to find the right balance of adaptation. The coach behavior should meet Japanese expectations but in the same time stay grounded in authenticity. It is a fine-tuning process to find the appropriate behavior that feels easy enough to show. It should still feel right for the coach, he or she should feel comfortable dealing with Japanese clients. Eventually, Molinsky suggests that the new behavior has to be repeated and trained, like a muscle is trained when doing sports. Feedback also helps.

Using global dexterity, the coach many develop the ability to adapt and shift his or her behavior in light of the cultural differences identified whenever necessary. Blending awareness, competence and some form of conformity with authenticity is key to successful coaching. The coach should be reminded that a coaching relationship is never culturally neutral.

3.2. Coaching roles and not personality

Building relationships is central to the Japanese culture and requires great attention. It has a lot to do with setting a proper atmosphere, as culturally accepted. The amount of time needed to establish such an atmosphere may be much longer than anticipated. The coach is culturally expected to take great care of the coaching space and to act as a host receiving guests (Dreyer 2012).

State-of-the-art coaching generally addresses goals focused on personality development. The coaching process often concentrates on personal values, passions, skills, and strengths, sometimes personality traits are highlighted. In a Japanese setting however, keeping these proceedings may not be productive. Recalling the many sociocultural aspects mentioned earlier, focusing the coaching process around the client’s awareness of his or her personality might not be productive. Having the coaching goals in mind, coach and clients should find a way that is culture sensitive. Since individuals are generally perceived in the Japanese environment as group members more than as individuals, focusing on what the client brings to his or her group sounds logical. Related to the specific situation and the specific groups at play, the coaching process may focus on the awareness of behaviors, rights, obligations, beliefs, and norms present or needed.

Coaching may thus emphasize roles, not personality. The client’s role includes his or her function within the group, the shared social norms, the group’s influence on the role, and the relationship between expectations and behaviors. It helps to deal with emotions on the one side and imperatives like keeping one’s face, keeping conformity, consensus and harmony on the other side. As Dreyer (2012) puts it, coaching in Japan is not a consideration of self but a quest for coherence of relationships with the situation.

Again, emotions are generally not shown in public. When coaching on roles, the coach may listen to the client’s mood and disposition as well as the atmosphere developing during sessions. The coach should listen to the implicitness included in the client’s answers too. Accordingly, questions related to feelings are mostly not welcome, if taken seriously at all. Questions and action plans should respect the client’s face and be as indirect and polite as possible.

3.3. Systemic Constellations Coaching

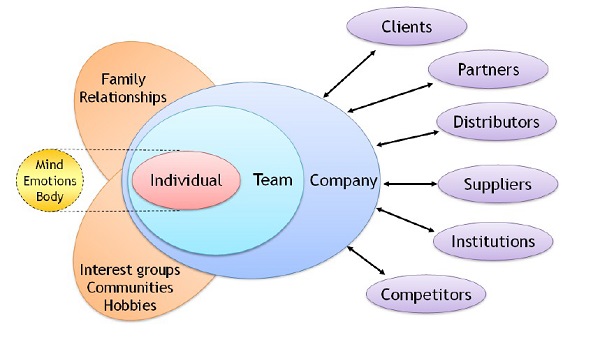

The Japanese culture stresses the importance of groups for the individuals and their identity. Complex relationships and networks of obligations exist at various levels, as seen before. Loyalty to the in-group is a key feature that helps keeping cohesion, consensus and conformity. Coaching focused on individual development may endanger the client as his or her loyalty could be at stake. We have seen that one possibility would be to highlight roles. Another possibility to practice coaching with Japanese sounds even more promising: aiming the attention around the relationships themselves.

Coaching around networks of relationships and systems is a fundamentally different approach. It does not focus on the individual alone, as an isolated person, but as always integrated in systems like family or organizations. Much of the coaching process is set around the awareness of the relationships and the networks around the client. It looks at the context in all its complexity and enables the identification and understanding of the relationships that are functional and the ones that are disruptive for reaching the goals set. Acknowledging this may allow the client to look at some issue with a different perspective, to take action on the relationship level, and bring back order and harmony aligned with coaching and client’s goals.

Picture 2: The Systemic View. Francesco Pimpinelli, SystemAlive®: http://www.systemalive.com

Picture 2: The Systemic View. Francesco Pimpinelli, SystemAlive®: http://www.systemalive.com

This approach is called systemic coaching or systemic constellations coaching (Whittington 2012). Simplifying, according to the systemic approach, any actions the client may take will influence his/her environment, the relationship he/she has with the systems around him/her and eventually the systems themselves. Consequently, the client needs to consider the systemic constellation around when taking action as well as the consequences his/her actions may have on the systemic constellations.

Using a systemic coaching approach with Japanese clients enables to save or restore coherence, integrity and authenticity. It consists of a set of tools which enable clients to visualize, to see the whole and to acknowledge what is. It helps the client to identify the really important elements who need attention during the coaching process. It ensures that they find the right place in their system and reach their goals in harmony with their environment.

It is now clearer how challenging coaching in Japan might be. Sociocultural elements of the Japanese culture require special attention to enable the coach and the process to be effective. We were able to highlight a few avenues that may help to deliver an authentic coaching experience adapted to a Japanese environment. Coaching roles and systems sound very promising ways to deliver great value to clients in Japan or to Japanese clients over the world.

These results are likely to be transferable to other national cultures and other settings. However, we remind here again of one great limitations of this paper: the subjectivity and the unavoidable ethnocentrism of the author. In addition, we are aware that in bringing some traits to more salience, some assertions may be perceived as stereotyped. We recognize that Japanese people are unique individuals with a free will and may not feel well portrayed.

Great value could have been added if some of the statements and findings had been better documented by academic research. Due to lack of time and resources, the author could not ensure that. It would be a great complement to that paper if especially qualitative research projects including interviews of Japanese people about their expectations and experience of coaching could be carried out, to corroborate or invalidate findings presented here with humility.

References

Chhokar, Jagdeep S., Brodbeck, Felix C., House, Robert J. (eds., 2008). Culture and Leadership across the World: The GLOBE Book of In-Depth Studies of 25 Societies. New York: Taylor & Francis.

Dreyer, Peter (2012). Dienstleistung aus der Distanz: E-Coaching in Japan. In: H. Geißler & M. Metz (eds.), E-Coaching und Online-Beratung (pp. 301-318). Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

Galef, David & Hashimoto, Jun (2012). Japanese Proverbs: Wit and Wisdom. Tokyo, Vermont and Singapore: Tuttle Publishing.

Haidt, Jonathan (2012). The Righteous Mind: Why Good People are Divided by Politics and Religion. New York: Pantheon Books.

Hall, Edward T. (1963). “A System for the Notation of Proxemic Behaviour”. American Anthropologist 65 (5): 1003–1026.

Hall, Edward T. (1976). Beyond Culture. New York: Anchor Books

Hall, Edward T. (1983). The Dance of Life: The Other Dimension. New York: Doubleday

Hall, Edward T. & Read Hall, Mildred (1990). Hidden Differences: Doing Business with the Japanese. New York: Doubleday.

Hofstede, Geert (2nd edition, 2001). Culture’s Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions and Organizations Across Nations, Thousand Oaks CA: Sage Publications.

Hofstede, Geert, Hofstede, Gert Jan & Minkov, Michael (3rd edition 2010). Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind. New York: McGraw-Hill.

House, Robert J., Hanges, Paul J., Javidan, Mansour, Dorfman, Peter W., & Gupta, Vipin (eds., 2004). Culture, Leadership, and Organizations: The GLOBE Study of 62 Societies. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

International Coach Federation. www.coachfederation.org

Itoh, Mamoru. http://www.itoh.com/profile/

Kippenberger, Tony (2002). Leadership styles. Oxford, UK: Capstone Publishing.

Kopp, Rochelle (2012). Defining Nemawashi. 2012/12/20, Blog last retrieved on 2015/10/30, http://www.japanintercultural.com/en/news/default.aspx?newsid=234

Molinsky, Andy (2013). Global Dexterity: How to Adapt Your Behavior Across Cultures without Losing Yourself in the Process. Boston: Harvard Business Review Press.

Pimpinelli, Francesco. http://www.systemalive.com

Rosinski, Philippe (2003). Coaching Across Cultures: New tools for leveraging national, corporate & professional differences. London: Nicholas Brealey Publishing.

Schneidewind, Dieter (1991). Das japanische Unternehmen. Uchi no kaisha. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Verlag.

Sterlacci, Peter (2012). Branding ‘me’ in a ‘we’ culture. Japan Today, 2012/07/25, last retrieved on 2015/10/30, http://www.japantoday.com/category/opinions/view/branding-me-in-a-we-culture

Tanaka, Takashi (2013): Coaching in Japan. In: J. Passmore (eds.), Diversity in Coaching: Working with Gender, Culture, Race ans Age (pp. 147-159). London: Kogan Page.

Trompenaars, Fons & Hampden-Turner, Charles (1997). Riding the Waves of Culture: Understanding Cultural Diversity in Business. London: Nicholas Brealey Publishing.

Whittington, John (2012). Systemic Coaching and Constellations: An Introduction to the Principles, Practices and Application. London: Kogan Page.

Yoshino, Kenya (2015). Learn the Invisible Rules of Japanese Companies. Japan Today, 2015/10/21, last retrieved on 2015/10/30, of-japanese-companies