Research Paper By Lionel Bikart

(International Leadership Coach, JAPAN)

Human beings are not what they are once and for all, they are open. They do not know one solution, not one realization as the only right and true. – Karl Jaspers

It is impossible to remain indifferent to Japanese culture. It is a different civilization where all you have learned must be forgotten. It is a great intellectual challenge and a gorgeous sensual experience. – Alain Ducasse

Many modern management concepts were born or theorized in the USA. Some travel good to other nations, some cannot be efficiently applied in other cultures, some need an adaptation to make sense. Professional Coaching as supported by ICF – the International Coach Federation – seems to be universal and practiced successfully around the globe. The ultimate purpose of coaching is the client’s personal development. Japan has a unique culture rooted in values like harmony, conformity and the primacy of groups over individuals. In the worst case, supporting a Japanese client with coaching to develop themselves may endanger societal values, causing among others disharmony and may result in their exclusion of the group. As a Japanese proverb says, a nail sticking out should be hammered down. Still, coaching in Japan has been existing for more than 20 years and is continuously growing. In this paper, we will explore professional coaching in the light of the Japanese culture and its uniqueness. We will suggest implications for the coach and the coaching process of partnering with Japanese clients.

From the very beginning, we are aware that this paper will not suffice criteria of objectivity. Everything written by the author about Japan, its culture and its people, no matter how well supported by research, will remain fundamentally ethnocentric. At all times, knowledge is influenced by language and culture. Writing about other cultures does not erase the cultural background of the author. In addition, parts of this text are fed by the authors subjective observations and considerations born from ongoing three and a half years of life in Japan.

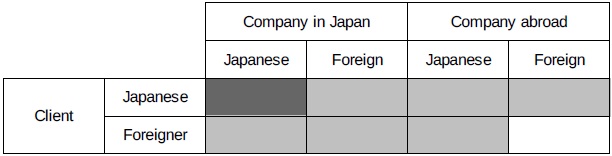

In the following, we will focus on professional coaching in corporate settings. Four types of individual coaching clients in Japan may be considered, as shown in the table below: a Japanese working for a Japanese company; a Japanese working for a foreign company; a foreigner working for a Japanese company; or a foreigner working for a foreign company. Similar situations exist if the clients is outside of Japan. In order to make the particularities of coaching with Japanese as salient as possible, we will concentrate on the first case: a Japanese working for a Japanese company in Japan. Some implications will be valid for the others settings of course. The coach being Japanese or not will add another level, that we discard here.

Table 1: Coaching situations taking the Japanese culture into consideration

Table 1: Coaching situations taking the Japanese culture into consideration

To analyze the implications of the Japanese culture for professional coaching, we will first present a few aspects around coaching that may need consideration in Japan. Second, we will take a closer look at the particularities of Japanese clients and the Japanese culture relevant for the coaching process. Third we will draw a few avenues for coaches to successfully coach Japanese clients.

1. Considering Coaching in Japan

ICF, the major association of coaches worldwide including in Japan, provides a definition of coaching: Coaching is “partnering with clients in a thought-provoking and creative process that inspires them to maximize their personal and professional potential”. Further, ICF supports that “coaches honor the client as the expert in his or her life and work and believe every client is creative, resourceful and whole.” Responsibility of the coach is to monitor the process of (1) discovering, clarifying, and aligning “with what the client wants to achieve”; (2) encouraging “client self-discovery”; (3) eliciting “client-generated solutions and strategies”; and (4) holding “the client responsible and accountable”. The aim of coaching is to improve the client’s “outlook on work and life, while improving their leadership skills and unlocking their potential”.

We will see later in more details that some of these aspects may be problematic in Japan considering the national culture. One of its characteristics is to value conformity and general interest, group or company interests prevail over individual interests. Stating what one’s ambitions are, striving for self-discovery and assuming one’s individual opinion may not be as easy and desirable for Japanese as it is in the Western world They may not even think in these categories. In addition, even though the coach may hold the client as the expert in their lives, societal cues may alter that perspective.

Nonetheless, ICF requires their affiliated coaches to respect that definition. ICF also demands their member to behave according to the ICF Code of Ethics, what should not be problematic, and determines 11 core competencies that all coaches should master. Even though these requirements are oriented to the coach and the coach should “dance in the moment” with the clients in the sessions, the application of some competencies in Japan may be subject to great care. Some competencies will gain great importance with Japanese, like establishing a coaching agreement based on a strong trustful relationship. Intimacy is however not well accepted in a culture where emotions are only shown in the private sphere. Also, when the coach’s position may be culturally similar to a teacher or mentor, Japanese clients may tend to stay silent and rather eager to listen to the coach. Raising questions related to one’s opinion may be perceived as impolite. And direct communication may be perceived as not culturally sensitive, so that great awareness in applying coaching skills is necessary.

Coaching is generally about self-realization, emphasizing strengths, values and purpose, creating awareness, questioning, listening to emotions, shifting disempowering perspectives and beliefs, etc. All aspects that are applicable in a Japanese environment too, but much greater care, cultural sensitivity and empathy is required from the coach.

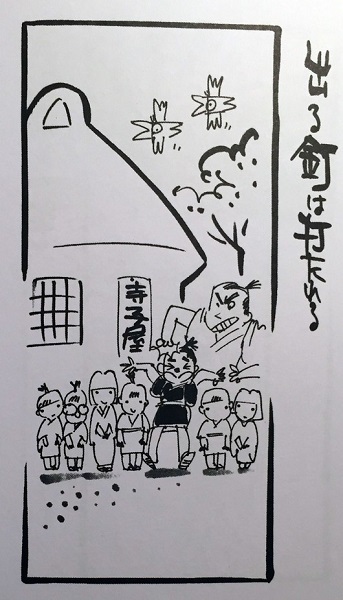

Unless the client formulates it as a coaching goal, coaching should not foster more individuality. Indeed, group conformity is one of the key social norms. A famous Japanese proverb says 出る杭は打たれる (deru kugi wa utareru), meaning that any nail which sticks out will get hammered down – Picture 1. Any deviation from the norm will not be tolerated. Only (apparent) conformity is expected.

So how far can coaching support the “’me’ in a ‘we’ culture” (Sterlacci 2012)? How far can a Japanese client, living in Japan and working in a Japanese company identify and emphasize his or her authentic self, without risking being banned from their group? That might be a westerner’s question in the eyes of Japanese people. But if stressing one’s individuality may endanger in-group identity, how might coaching be effective? Sterlacci in his article suggests considering the following dimension: self-development vs group goal; growth and progress vs tradition and precedent; competition vs collaboration; and individual achievements earned and rewarded vs attribution of success and position.

Even though coaching in Japan seems challenging from a Western point of view, the coaching market is sizable and keeps growing since its official introduction in the late 1990s by Mamoru Itoh. Itoh got to know coaching through ICF and in the USA and offered a coaching training in Japan as early as 1997, setting the foundation for the Japan Coach Association (1999), which is still close to ICF, recognizing its code of ethics and credentials, but not a national chapter. In 2002, The Japan Coach Federation was created. As for the ICF Japan chapter, it was founded later, in 2008. We could not find solid information concerning the number of coaches in Japan and the market size. The 2012 ICF Global Coaching study registered 183 respondents, which will by no means reflect the true number of coaches in Japan. However, a few coaching schools seem to register an increasing number of graduates, many books on coaching can be found in Japanese book stores and the concept seems to be known by more than a few people around the country.

To summarize, the unique Japanese culture seems to challenge a few assumptions fundamental to professional coaching as understood by ICF. How far can coaching in Japan be run effectively in a similar way as in the Western world remains unclear. Nonetheless, profession coaching is present in Japan and developing. Let us now turn to some characteristics of the Japanese culture and how they might influence the coaching process.

2. Japanese culture and its possible impact on professional coaching

As any national culture, the Japanese culture will heavily impact the way Japanese coaching clients will perceive moral, norms, values, creating beliefs, behaviors and attitudes. In corporate settings, the organization culture will additionally impact individuals, but that is not our subject here. In the following, we will introduce frameworks for analyzing national culture, helping us to characterize the Japanese culture. We will then present a few sociocultural elements of the Japanese culture deeply impacting the attitude of Japanese people and draw possible implications for coaching. We will eventually do the same with unique features of the Japanese management culture.

2.1. Cultural frameworks, Japan and coaching

2.1.1 Moral Foundations Theory

The Moral Foundations Theory explains why morality varies across cultures. It identifies six dimensions which are postulated universal, at the foundation of ethics (Haidt 2012). Virtues and Narratives are constructed on them, creating the unique moralities attached to one culture. The dimensions and some associated virtues are:

The idea is that all cultures create virtues and norms based on stories defining morality. Each culture interprets these dimensions differently, defining what is right and what is wrong in a unique way. Recognizing a common foundation of morality may help the coaching relationship, bringing awareness on similarities and differences and passing through the right or wrong proposed by judgment. In Japan for instance, in-group loyalty can be observed as very strong.