Research Paper By Kombe Temba

(Life Coach, ZAMBIA)

Introduction

The complementary relationship between Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) and Emotional Intelligence (EI) model provides a useful framework for coaches to help their clients see the role their thoughts, emotions, and behavior play in their current situation, and how they can change that role to bring about progressive change in their lives.

CBT theory posits that our thoughts, feelings, and behavior are intimately linked and have an impact on one another – our thoughts affect our emotions; our emotions determine how we act; and this in turn influences what we think of ourselves. CBT is typically used as a short term action-oriented form of therapy that involves identifying and challenging negative thoughts, to help clients see how they can interrupt their thought patterns and change their behavior. In a coaching context, helping a client see a connection between their thought triggers, thoughts, emotions, and behavior can open up a new perspective and course of action that can move them forward.

Some useful insights for coaching come from the pioneers of CBT Albert Ellis and Aaron Beck, who pointed to the salient role our interpretation of events (as opposed to the events themselves) play in our chosen responses, and that correcting cognitive distortions (unhelpful, self-defeating thought processes) such as catastrophizing (expecting the worst to happen) or polarization (all or nothing thinking) leads to more accurate experiences of reality.

The term EI was originated by Peter Salovey and John D. Mayer. The concept was later popularised by Daniel Goleman who offered a model with four pillars:

The pillars can be grouped as follows:

- Awareness of and mastering our emotions(self-awareness and self-management)

- How awareness of other people’s emotions can regulate our behavior towards them and affect how we relate with them (social awareness, and relationship management).

The role of CBT and EI in coaching

The Socratic method of questioning is used as a CBT practice. It originated with the Greek philosopher Socrates who used questions to encourage people to enquire about the accuracy of their way of thinking. In a coaching space, Socratic questioning can help the coach uncover what the client already knows by asking open-ended questions, or offering observations that the client can reflect on.

This form of inquiry is essentially about uncovering the client’s truth of not only who they are but also the impact that their thoughts, beliefs, assumptions, and values have on their perspective of the issue that is plaguing them. Ultimately, the aim is to support the client to become aware of underlying thoughts, emotions, beliefs, and opinions then use this awareness to gain a new perspective that can help them move towards their goal.

Uncovering limiting beliefs for example, if done with self-judgment can bring in negative energy and prevent the client from moving forward. This is where self-compassion and self-empathy play a powerful role as they allow the client to sit with their discovery, own it, and decide what to do with it. Byron Katie created a simple and helpful approach to support this form of gentle inquiry, called The Work and she refers to it as “meeting your thoughts with understanding”(Katie and Mitchell, 2002: 4). The simplicity comes from the four questions that the client can apply to a thought (Katie and Mitchell, 2002: 15):

- “Is it true?”

- “Can I know that it’s true?”

- “How do I react when I think that thought?”

- “Who would I be without the thought?”

The first two questions help the client establish the validity of their thought and create an opportunity to get to the underlying belief. The third question speaks to the associated emotions and behavior that come up when that thought comes about, and the fourth question challenges the client to reframe their perspective of the situation around that thought.

CBT provides a framework for uncovering how specific behavior comes about, understanding it, and using that understanding to do things differently, as follows:

Once the client becomes aware and understands how their thoughts, emotions, and actions are working together to produce an undesirable outcome, the coach can then support them to interrupt that behavioral pattern. This is an opportune time to integrate EI into the coach’s approach because as the client develops more awareness of their emotions, they can further be supported in learning how to practice regulating them when triggered. Since emotions are a key driver of our behavior, understanding the triggers and accompanying thoughts can help the client choose a different response from their habitual one.

Let’s take a client who has feelings of guilt and anger. The coach can invite them to recall the last time these feelings showed up this way. In this case, the client explains that whenever they hear critical or negative sentiments about single parents, they recall their challenging and lonely experience as a single parent. This evokes feelings of anger and guilt because they do not get financial support and can’t provide the kind of material support that two parents would have provided their children, so they get offended and become defensive towards the purveyor of such sentiments.

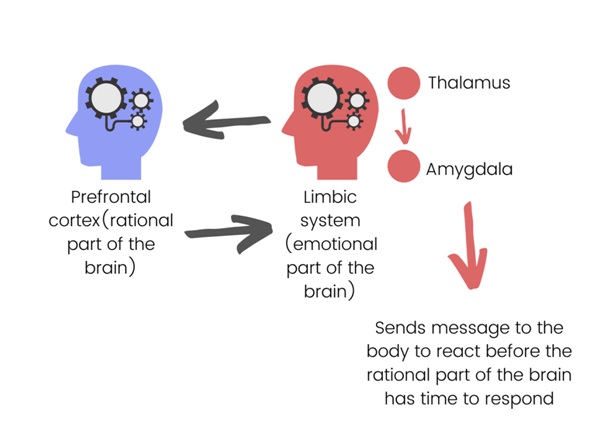

This self-discovery by the client can further be supported by EI which provides a helpful way to understand that there is space between the stimulus and response (the trigger and behavior) and that we can learn how to use that space effectively so that we move from reacting impulsively to responding thoughtfully. This space is derived from how our brains function and the following image is a simplified depiction of it:

The limbic system is the main actor in the fight, flight, or freeze reaction, which is our body’s natural reaction to perceived threats of danger. Ordinarily, the thalamus (found the limbic system) receives sensory information from our eyes for example, and sends it to the prefrontal cortex (the rational and analytical part of the brain) which takes time to process the information and provide an appropriate response to the limbic system, which in turn communicates that response to the body. This process represents the space between stimulus and response.

However, the thalamus also sends a shorter signal to the amygdala (also found in the limbic system) which does not wait for any further information and promptly springs into action by reacting to the perceived threat. This short cut, also known as ‘emotional hijacking’ shortens that space between stimulus and response and replaces it with a fight, flight or freeze reaction.

How can we support the client who is experiencing anger and guilt to identify and make the best use of that space so that they transition from reacting to responding to their triggers? There are two helpful tools that both CBT and EI espouse – practicing mindfulness and journaling.

Mindfulness can be described as the act of purposely becoming aware of what is happening in the present moment and being fully engaged in it. The emphasis is on being fully present and bringing stillness into that space between stimulus and response. A useful and simple acronym that clients can be offered as a mindfulness aide is S.T.O.P. by Elisha Goldstein:

S Stop (literally);

T Take some slow deep breaths;

O Observe your experience as it is. Notice the emotions, physical sensations, energy, and visions that are present;

P Proceed with a helpful action.

Journaling is a practical way of downloading our thoughts directly onto paper in a way that is authentic and safe for us. Writing down our thoughts helps us to clarify them, release emotions that have been bottled up, identify emotional triggers, and highlight behavioral patterns.

Targeted journaling can help clients focus on areas that they want to work on, for example, limiting beliefs or troubling emotions. The CBT framework outlined above provides a format to help clients see the thought and behavior patterns that are not serving them. Capturing what happened, how it happened; what was going through the client’s mind at the time; how the client felt; and how they behaved at that moment provide a reference point from which they can observe these patterns over time.

The EI model by Daniel Goleman is also a source for a targeted journaling format that focuses on understanding emotional triggers and habitual reactions, for example by inviting a client to write down what happened or was said to them; how they felt in the moment; what they did at that moment; and how they felt about the same event a day later. This not only helps the client see how their emotions influence their behavior but also how the passage of time impacts the emotions they experience much later. This period represents the space between stimulus and response and it shows the client that there is an opportunity to change their behavior in that space.

Getting back to our angry and guilt-ridden client, we can see how introducing an intentional pause between the emotion and response can introduce a different way of responding to those negative sentiments about single parenting, while capturing the thoughts, emotions, and behaviors around the trigger can help the client see patterns that they can interrupt to develop behavior that supports forward movement and personal growth.

Conclusion

Coaching is about the coach providing a safe space for the client to present their intentions and goals authentically, and to progressively explore how they are relating with their issues (via their thoughts, beliefs, values, and emotions) in a way that helps them move forward and eventually achieve their stated goal.

CBT theory and EI models demonstrate how the client can identify and understand the relationship between their thoughts, emotions, and behavior, and see that it is possible to intentionally use the space between stimulus and response to get the outcome they aspire for.

While Socratic style questioning, mindfulness practices, and journaling are methods used in CBT and EI practice, the coach can supplement these with gentle self-inquiry by the client and invite them to make effective use of the space between stimulus and response, by stopping and using what they observe about themselves at that moment to inform their response.

Supporting the client to gain an understanding of what triggers unhelpful thoughts, the emotions that come up, and how they behave, as a result, can open up new ways of looking at the same situation. Additionally, helping the client to question the validity, accuracy, and truth of unhelpful thoughts with self-compassion rather than judgment, is more likely to lead them to a place of acceptance, to a willingness to do things differently, and get the result they want. This opportunity to respond differently to their situation subsequently gives the client fresh insights as they plan and a renewed energy with which to intentionally move forward towards their goal.

References

Clark, R.K. (2005). Anatomy and physiology : understanding the human body. Sudbury, Mass.: Jones and Bartlett Publishers.

https://www.klearminds.com/blog/history-cognitive-behavioural-therapy-cbt/

https://www.mindful.org/stressing-out-stop/

https://positivepsychology.com/emotional-intelligence-goleman-research/

https://psychcentral.com/lib/the-health-benefits-of-journaling/

https://www.simplypsychology.org/cognitive-therapy.html

Goleman, D. (2006). Emotional intelligence. New York: Bantam Books.

Katie, B., and Mitchell, S. (2002). Loving what is : how four questions that can change your life. London: Rider.

McLeod, S. A. (2019, January 11). Cognitive-behavioral therapy. Simply Psychology.

Robinson, E. (2019). Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Techniques: How to Manage Anxiety and Depression Using CBT – Control Your Thinking, Emotions, and Behavior. Kindle Edition.