Research Paper By Kate McShane

Research Paper By Kate McShane

(Career Coach, UNITED STATES)

Client: “I want to look for a job, BUT I am too anxious.”

Coach: “You want to look for a job, AND you are anxious about it.”

As a student coach, I am in the exploration process on many levels; niche, model, session design, ideal client, resources, and more, but I do possess clarity in at least one area. I have spent the last 30 years of my career helping the unemployed and underemployed secure jobs that provide training, advancement, and a path out of poverty. As my vision for my practice evolves, I am hoping to build on this experience and envision establishing a blended career coaching practice. My heart remains with those who struggle to find their path.

Having partnered with hundreds of clients through their search for meaningful work, I am awed by the perseverance of the human spirit in the face of adversity, and a fierce believer in the transformative power of securing the “right” job. have witnessed the power of hope and shared in the excitement of the client who realizes their unique gifts and achieves their career goals. However, I have also witnessed the struggle of many as strong feelings of anxiety, unworthiness, and incompetence impede or prevent their progress. To that end, I was exploring resources that may help the client navigate this aspect of the job search process. In my investigations, I happen upon Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) and was interested in learning more. I appreciated its approach to normalizing and navigating difficult emotions and the techniques it offered for forwarding movement in the midst of the struggle. Drawing on ACT’s approach and techniques for navigating through emotions instead of around them and committing to action steps in the presence of them, resonated with me as an effective approach to utilize. I also recognized that much of ACT’s methodology aligned with the ICF competencies, which, to my mind, increased its credibility.

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy operates on the belief that we need to accept our negative thoughts, emotions, and memories as part of the human experience, while simultaneously committing to actions that align with our values and goals (The ABCs of ACT, 2008).

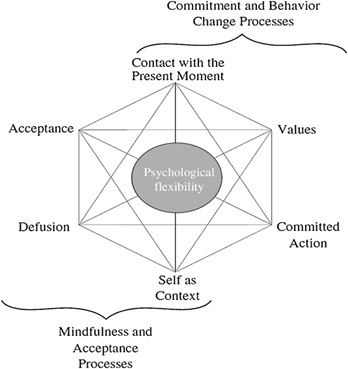

ACT focuses on enhancing an individual’s psychological flexibility by “increasing acceptance of current circumstances as well as internal experiences, confronting experiential avoidance, contextualizing problematic cognitions, exploring personal values and associated goals, and fostering commitment to moving forward in the direction of one’s chosen life values” (Hayes). Many of these same phenomena are encountered in the career counseling arena, suggesting ACT’s usefulness for coaches interested in developing this area of expertise.

Stephen C. Hayes, Professor of Psychology at the University of Nevada, developed the theory in 1986, largely in response to his experience overcoming debilitating panic attacks. His colleagues, Kelly Wilson, and Kirk Stosahl worked to develop the theory further.

This empirically based approach evolved from the field of psychology called behavioral analysis and is based on the behavioral theory of cognition known as Relational Frame Therapy. It belongs to the school of behaviorism known as functional contextualism, which focuses heavily on people’s thoughts and feelings. It is part of the third wave of behaviorism characterized by mindfulness, acceptance, and compassion practices combined with traditional behavioral interventions. ACT focuses on changing the impact of our negative thoughts versus attempting to change the negative thoughts themselves. Clients learn to respond differently to negativity and accept their thoughts, develop greater clarity about personal values, and commit to needed behavior change. (Harris,3)

The overarching goal of ACT is building an individual’s psychological flexibility, defined as, the ability to act mindfully, guided by our values. ACT practitioners utilize six overlapping core practices to build a person’s psychological flexibility; contacting the present moment, cognitive defusion, acceptance, self-as-context, values, and committed action. With a greater degree of psychological flexibility developed as a result of practicing these six core areas, the client better responds to life’s challenges, while at the same time remaining engaged in value-based actions that generate meaning and purpose and increase life’s vitality. It is not necessarily a state of happiness or ease, but more the ability to flexibly navigate through the changing demands of life when difficult thoughts and feelings arise. (Harris,8). Focus on enhancing psychological flexibility may be particularly useful for clients who are navigating the complexities, competitiveness, and insecurities in the current labor market (Yates).

This paper will explore each core practice in more detail below and where appropriate, highlight its relevance in a career coaching environment.

Present Moment Awareness

Present Moment Awareness or Mindfulness is a central component of ACT. For the client, learning about and engaging in mindfulness practices helps to bring about present moment awareness of thoughts, feelings, bodily sensations, and the surrounding environment, in a value-neutral observant manner. The client pays attention to his thoughts and feelings, accepts them as is without labeling them as good or bad, and attempts to let them pass without getting hooked by them. They allow the present without resistance. This response allows the person to focus on and stay connected with the “here and now”. This moment-by-moment awareness frees the person to tune into the present rather than getting lost in regrets about the past or getting anxious about the future (McClure).

Dealing with unemployment, underemployment, life-altering decisions around educational plans, and the likelihood of rejection typical of many job searches can be a source of tremendous anxiety and may trigger concerns around competence and worthiness. Mindfulness practices assist the client in identifying and experiencing these feelings with self-compassion without getting hooked or derailed by them.

Acceptance

ACT practitioners teach the client through mindfulness practices to open up to all feelings and realities, in other words, to accept what is exactly as it is. The client accepts uncomfortable sensations, painful memories, physical pain, negative thoughts, and tough emotions without resistance. Instead of viewing these uncomfortable occurrences as a problem, clients learn to recognize them as a normal part of the human experience. The person then realizes that having the full range of thoughts and emotions is part of life’s journey, not an aberration that needs to be eliminated or repaired or avoided. Regularly utilizing mindfulness exercises, clients develop an acceptance and awareness of the present moment and increase their willingness to experience and embrace unpleasant emotions and sensations as opposed to fighting or numbing them. (McClure)

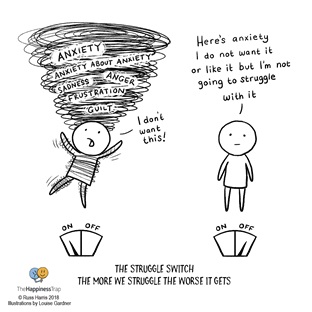

Without acceptance, human beings often default to experiential avoidance, which is our normal desire to avoid or get rid of unwanted thoughts, feelings, memories, and emotions (Harris, 27). The ACT stance is that thoughts and feelings are not problematic in and of themselves; it is only when we try to avoid or control them, that they have problematic effects (Harris, 27).

Examples of experiential avoidance include getting busy organizing one’s closet when the task at hand is to write a resume or canceling an interview because of high anxiety. There is momentary relief perhaps, but in the long-term, our suffering is increased as we fail to move in the direction of an authentic, values-based, and vital life. Ironically, in our attempts to control or avoid unwanted feelings, we intensify our experience of them and deepen our suffering (Hayes).

For example, Kelly is a client who cares deeply about advancing in her career but is experiencing strong feelings of anxiety about accepting a more senior role within her company. Her anxiety is so profound, she fears she will decline the job offer. In an ACT approach, her coach would help her turn toward her anxiety and experience it fully and without resistance. Her feelings of anxiety would then be normalized with the assurance that many people experience anxiety before taking their next career step; that it is perfectly normal and alright. The coach can then help her understand that her anxiety need not be changed, avoided, or removed for her to move in the direction of her values. The goal is not to change the negative feeling, but instead, change the impact of the feeling by accepting it and continuing to move forward despite it (Luken & De Folter).

Cognitive Defusion

People tend to identify with their inner dialogue and memories. The thought or memory then becomes merged or fused with an individual’s sense of who they are. ACT does not attempt to change or get rid of these negative thoughts, but instead with Cognitive Defusion, helps the client identify less with their negative feelings and emotions and take them less literally (Luken & De Folter).

Cognitive Defusion is a term unique to ACT and is the ability to see one’s thoughts from an objective perspective rather than getting caught up in them. The goal of Cognitive Defusion is to detach or step back from one’s thoughts and emotions to lessen their negative impact. With Cognitive Defusion, clients note negative thoughts and observe them unemotionally, allowing them to accept the feeling, but creating space between the thought as self to the more direct reality of the self having a thought (McLure). So, for example, “I am unemployable”, shifts to “I am having thoughts about being unemployable”. This technique helps create space between the thought and the thinker/observer.

With this shift in awareness, clients begin to realize that they are not their thoughts, they are instead the observer of their thoughts. The negative thoughts and emotions do not define the self, but rather are experienced by the self. With this new knowledge, clients are further encouraged to objectify the emotion with any of a variety of techniques such as, assigning the emotion a name or shape, having a conversation with the emotion, or repeating the disturbing thought over and over until it dissolves into sound. All of these methods aid the acceptance of the thought or feeling and also serve to weaken its ability to interfere with positive action steps toward achieving one’s goals (McClure).

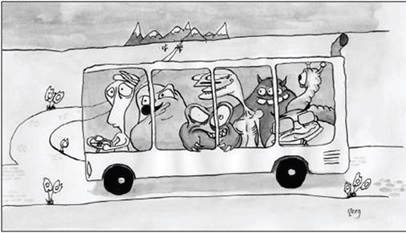

ACT’s objective in using cognitive defusion is to build the client’s understanding that the negative thoughts and emotions are merely that, fleeting thoughts and emotions that are transitory and will pass. They need not be in control of a situation or plan of action. ACT utilizes many fun metaphors, exercises, and stories to help clients understand and benefit from these six core practices. One of the most common ones, Passengers on the Bus, is used to illustrate Cognitive Defusion. It goes as follows:

Life is like a bus, and you are the driver. The passengers represent your memories, thoughts, emotions and physical sensations. On the bus, there are some of these annoying passengers. hey yell at you to turn left or right, warn you of “big dangers ahead’ and sometimes suggest shortcuts…but at what costs? You alone can decide the direction to take, the one that is true to you. By accepting the presence of annoying passengers, by calmly telling them they are welcome but must sit in the back of the bus, by learning to listen to them without necessarily doing what they say, you alone take control of the wheel and channel your actions in the direction that’s fulfilling to you (Harris).

Self-as-Context

ACT defines Self-As-Context (SAC) as the “observing self”: that aspect of a human being that does all the noticing/observing of one’s inner and outer world. The construct of self-as context is the awareness of one’s awareness. Clients learn how to tune into thoughts, feelings, actions, and the world around them, and then to pay attention to the self that is doing the noticing. SAC is that aspect of us that is aware of whatever we’re thinking, feeling, sensing, or doing in the present moment; it is both constant and unchanging (www.theactmatrix.com).

This is in contrast to self-as-content, which is one’s story of who they are including objective facts (e.g. name, age, sex, marital status, occupation), descriptions and evaluations of the roles we play, our strengths, weaknesses, our likes, and dislikes, and our hopes, dreams, and aspirations. When we fuse with our self-concept, we believe that our narrative is the reality of who we are (Harris). ACT’s stance is that believing and merging with our language, cognitions, and memories, is the source of much suffering as we inevitably mistake our thoughts about ourselves as the essence of who we are. Our self-descriptions and internal rules, perceived as self, shape, and cloud our reality. It does not reflect the wholeness, continuity, and calm center of the “observing self, but merely our internal dialogue about who we are (Harris).

Starting with the foundation of career guidance by Parson in 1909, the self-as-content is utilized to lead the person through planning, goal setting, the job search, and guide the development of one’s career. This is still the case in the prevailing narrative approach to career guidance so often used today. Hence our internal narrative and language play a critical role in shaping our career aspirations and development. The ACT approach differs from traditional and current career models in that it considers language, our internal narrative, a source of human suffering because we so often confound the verbal world with reality. In career guidance adhering to the principles of ACT, the thinking part of ourselves (self-as content) is seen in an advisory role only, and self-as-context takes the dominant role that guides the process. Career guidance then becomes less about self-knowledge and more about self-concordance (Luken & De Folter).

By building one’s awareness of SAC, the client can enhance the three prior mindfulness skills of ACT; defusion, acceptance, and present moment awareness. SAC exercises to aid the client in gaining access to a stable sense of self – a “calm unchanging center” – from which she can notice her shifts in thoughts and feelings, changes in body and health, the adjustments that accompany a new role and or changed circumstances. Developing SAC reinforces that there is more to one’s self than one’s body, thoughts, feelings, and memories; more to one than the roles played and actions are taken. All these elements are continually changing throughout life, but the aspect of one that notices them is unchanging and always available. (Dewane)

Values

A central part of ACT is exploring and defining one’s values to achieve and engage in meaningful activities. The client reflects on what is most important to him; what will give his life meaning. Values are not achievable, in and of themselves but instead underpin decisions about the what and why of our actions. They serve as the lens to shape and live a life congruent to one’s principles and beliefs. They both guide and define, and inform one’s goal-making process.

The values of each individual are unique to that person. For one, it may include kindness and order, for another achievement and financial security, for still another joy and health. There are no right or wrong values, only a unique combination that resonates for each individual. Values must arise authentically from the individual, not out of societal influences or to please someone else. Inauthentic choices will constrict, whereas values guide. They must promote a commitment to action that is an outgrowth of one’s principles and beliefs, guide the client in the direction of his life’s purpose and sustain him as he creates a plan of action that is rewarding, sustainable, and creates a vital life.

Identifying values and setting career goals based on them has been shown to increase self-confidence (Yates, 140). Clients are encouraged to reflect on their career-related values and then identify goals that align with those values. Values can point the client’s in the right direction, but additionally, provide flexibility in the manner they are acted upon. So, for example, the desire to help people could point toward pursuing nursing, counseling, or community activist. There is room to explore many options which curtails all or nothing thinking and opens up new possibilities.

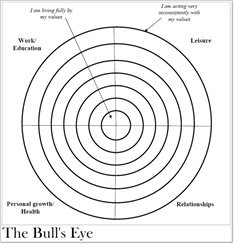

There are numerous methods for defining one’s values. For example, one can consider different areas of their lives such as Family, Health, Community, Social connections, Leisure, Parenting, marriage/partner/intimacy, Work/education, Spirituality, and Professional Development and shape their values by reflecting on each.

The worksheet below is often used in the ACT to assist in the values clarification process.

Or, there are a series of questions that can assist in identifying one’s values. Some possible questions include:

Committed Action

Committed Action involves linking one’s actions to one’s values. It is an important part of ACT and engages the client in undertaking tangible steps towards their goals. Once again, ACT‘s focus on goals and committing to action strongly aligns with the ICF competencies and is an essential part of any career-focused strategy.

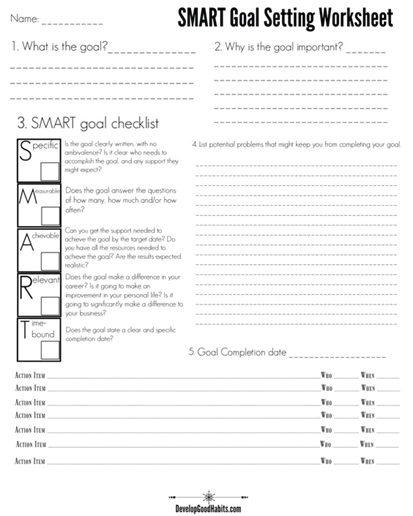

The client is encouraged to generate goals based on their values. In the next stage, the client is encouraged to set a series of measurable and observable goals, (complete BA in Education), followed by immediate short-term goals (study to prepare for upcoming exams) which assist the client in moving immediately in the direction of her goals. Complex goals are broken down into smaller more manageable tasks and concrete action plans. The client then commits to engage in agreed-upon activities in between sessions and the coach functions as a supporter and accountability partner (Luken & De Folter).

And much like the ICF competencies, the client is prompted to consider any potential barriers or obstacles, to build her emotional reserve when the inevitable setbacks occur. Taking steps forward to achieve one’s goals most often requires change and persistence and serves to expand the client’s range of approaches, which is increasingly possible as psychological flexibility builds. The individual is encouraged to move beyond previously unsuccessful attempts to achieve goals, and employ new behaviors and techniques, even if the process is unfamiliar and uncomfortable. As the client realizes her goals and conquers her fears, she gains more self-efficacy and starts on the path to living a more vital life in congruence with her values. As a result, self-esteem grows. (Harris)

its use has yet to be empirically studied. To date, there exist empirical studies of ACT’s effectiveness in providing good outcomes for stress and depression, and anxiety. And while these studies are not directly related to career counseling; stress, depression, and anxiety are frequently suffered by the job-seeker, thereby suggesting that ACT could provide some valuable tools in the career counseling environment.

Given the relatively small amount of research completed on the ACT in a career counseling setting, there are multiple opportunities to collect more data even before empirical research is designed and implemented. A valuable data collection point is the extent to which career counselors have been trained and are utilizing ACT. Coaches, counselors, and therapists could be asked to share their experiences in using ACT’s techniques and approach. While the collection of this data would be opinion-based only, it could be used to shape more empirically designed research.

Detailing the similarities and divergent points between existing career counseling theories and ACT could also yield some interesting insights. A study of ACT against the process variables of career counseling could also uncover ACT’s potential effectiveness in career counseling (Hoare, Hamilton, McIIveen).

Conclusion

ACT’s approach of accepting, without resistance, negative thoughts, feelings, and memories intrigued me and motivated me to learn more. I appreciated its honesty regarding the human condition: we will all have setbacks, suffering, and pain: it comes with the package of life. ACT suggests that the struggle to rise above or eliminate adversity is perhaps misguided, instead one should aim to go through it with kindness and self-compassion toward self. ACT develops the client’s coping mechanisms by teaching acceptance and mindfulness techniques, which serve to reduce the impact of negative thoughts, emotions, and memories, not the negative experience itself. But the reason for hope, in my mind, is while accepting life’s difficulties, the individual, at the same time, learns to move forward toward value-based goals. Life’s setbacks need not be a reason to stall one’s progress in life.

I also appreciated the belief ACT embraces that it is a natural human tendency to avoid negative thoughts and feelings not a mental or behavioral disorder. To my mind, this approach supported the ICF Competencies of a coach/coachee partnership based on the assumption that the client possesses the ability and inner resources to achieve his or her goals. They are viewed as whole and capable, not broken and in need of fixing. ACT offers many tools for working with clients in a career counseling environment.

References

Dewane, C. (2008). The ABCs of ACT – Acceptance and Commitment Therapy. Social Work Today. https://www.socialworktoday.com/archive/090208p36.shtml

Harris, Russ. The act was made simple. New Harbinger Publications, Inc., 2019.

Hayes, S. The Six Core Processes of ACT. Association of Contextual Behavior Science.

https://contextualscience.org/the_six_core_processes_of_act

Hoare, Nancey & McIlveen, Peter & Hamilton, Nadine. (2012). Acceptance and commitment

therapy (ACT) as a career counseling strategy. International Journal for Educational and

Vocational Guidance.

https://www.researchgate.net/

Luken, T., & Se Folter, A. (2019) Acceptance and Commitment Theory fuels innovation of Career Counseling.

https://www.academia.edu/

Richard, N., & Bleau, M., (2016). ACT in Career Counseling. CERIC.

https://ceric.ca/2016/10/act-in-career-counselling/

Yates, Julia. The Career Coaching Toolkit. Routledge, 2019