Research Paper By Jessica Lyons

Research Paper By Jessica Lyons

(Life Coach, UNITED STATES)

The Institute of Play reports 30% of people are engaged in their work in today’s world. In elementary school, 80% of students report being engaged and excited about learning at school (Institute of Play – About, 2014). This gigantic gap in engagement highlights a marked difference in our experience of the world as a child and what happens to that excitement as we grow up. Where does that engagement go? My answer is that we start thinking about “work” and what we “should do” and we stop inviting or learning through “play” which is ultimately essential to be able to live a fulfilled, creative, and happy life.

People find their way to coaching, both as clients and coaches for a multitude of reasons. Executive level clients might be looking to supersede their goals and breakthrough efficiency to enhance their possibility. Other clients come to coaching looking to evaporate the fog of confusion in their lives. They may be looking to make life transitions and need the accountability partners to make it happen.

Coaches often use imagination, guided imagery, and the power of metaphor to help clients climb up over the blocks that they have erected themselves. But what happens when the neurology that has created those blocks is entrenched in such a way that these blocks are difficult or impossible to overcome? Incorporating play as more than just an exercise, as a path to discovery is essential to catapult clients into the life that they have dreamed.

In order to examine play as a critical component of coaching—establish how one can coach playfully to aid clients in discovering the power of their play—we need a common definition.

Stuart Brown, author of Play defines play as

an absorbing, apparently purposeless activity that provides enjoyment and a suspension of self-consciousness and sense of time. (Brown, 2009, p. 17)

I found the “apparently purposeless activity” to be the most critical part of this definition. As coaches, we use exercises and design practices for clients to remove their mental blocks. Some of these mental blocks are so large that they require a lot of disintegration before they can be removed. Grounding clients in play and “apparently purposeless activity” exposes the client to new scenarios and perhaps new patterns that can unearth change. In the noise of our constant moving life, finding these purposeless activities can be a challenge.

It’s also important to distinguish here that “seemingly purposeless activity” does not necessarily refer to a “mindless activity.” A client not be inherently good at something they are playing with. In fact, it may be a skill that is garnered over time and practice.

Why We Play

Bob Fagen, a premier biologist studying animals at play, refers to play in bears

in a world continuously representing unique challenges and ambiguity, play prepares these bears for an evolving planet (Brown, 2009, p. 29).

The same can be said for humans and individuals seeking coaching. Technology has drastically changed the environment our grandparents grew up in and it will continue to evolve the world that we live in at a warp speed. We must use play as a practice that allows us to see solutions to problems we haven’t encountered before.

Where Does Play Come From?

Neuroscientist Jaak Panksepp – play research center at Washington State University – believes that play arises first in the human brain stem, where survival mechanisms such as respiration, consciousness, sleep, and dreams originate. This initial activation then connects to and activates pleasurable emotions that accompany the process of playing. (Brown, 2009, p. 60)

A later author believes that because this originates in this area of the brain, there are levels of play-processes that are at work when we are playing. Thus, not all play is equal.

There three different processes of play that humans and animals might engage in when they decide to play. Our physical movement (running or cardio vascular) is a more simplistic engagement in play and would be a primary-process of play. A tertiary-process of play is a much higher level of functioning aids the brain and the spirit in developing skills that are the most fun, new, and different allowing for expansion of human consciousness and connection with oneself. (Burghardt, 2010, p. 350)

Identify Your Client’s Type of Play Preference

Stuart Brown identified eight different personality types of play. This acknowledgement that we not only play in different ways, but that different types of activities are considered playful is important. Some clients may find great joy in participating in a competitive game with rigid structure and be able to reach their flow. Others, however, will find that do be difficult perhaps because they enjoy playing by collecting.

8 Personality Types of Play

- The Joker – revolves around some kind of nonsense

- The Kinsthete – people who like to move

- The Explorer – can be physical or emotional – seeking new places OR new emotions, experiences through music, movement, flirtation

- The Competitor – enjoys playing to win – enjoying competitive game with rules

- The Director – enjoys planning and executing scenes and events

- The Collector – to have and to hold, the most, the best collection of objects or experiences.

- The Artist/Creator – joy is found in making things

- The Storyteller – imagination is key to the kingdom of play

(Brown, 2009, p. 66)

It is critical to help clients use different types of play to stretch their senses. Engaging in a behavior or style of play that they may not have relied on in the past can create new pathways. It’s also important to acknowledge that if it feels like work, it probably is.

Cycle Of Play

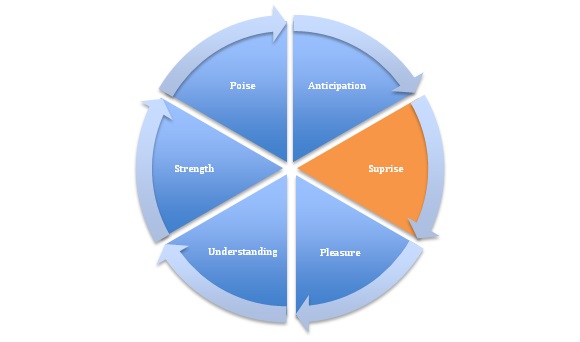

Scott Eberle, the founder of The Strong, National Museum of Play has identified a cycle of play that happens when we engage. A coach that is pushing and supporting their client in play, especially if play is not a natural practice must be aware of the cycle of play. There are clients that can be particularly goal focused in their play (a topic that I will touch upon later in this paper) and there may be parts of the cycle that a client prefers. Reflecting back parts of this cycle to help clients see their own patterns of strength and desire that emerge can be useful to highlight. The strength layer is one that can take longer to develop if the form of play is new or previously unknown (Brown, 2009, p. 19).

Coaching Techniques and Imagination

Coaching Techniques and Imagination

Coaches in particular employ the play strategy of the storyteller. We are often helping our clients uncover their story and then decide how they want to rewrite their story to live their life fully. We are invoking the power of imagination and enabling clients to play with that aspect of themselves.

Martha Beck specifically calls upon the techniques used in imagination and metaphor extension to assist people in expanding the play sides of themselves. She believes that imagination alone empowers clients to do fantastic things in their lives that they may not have otherwise accomplished. The small bit if suspended disbelief can allow room into what clients previously thought possible.

Possible Theories Behind Play

The most resounding theory about the importance of play might be to help us face our existential dread.

The individual most likely to prevail is the one who believes in possibilities – an optimist, a creative thinker, a person who has a sense of power and control.

Therefore, even when he individual is mucking around in the fear, they are still imagining and it’s possible for them to This leads to

the willful belief in acting out one’s own capacity for the future (Sutton-Smith)

Forge New Rivers- Retrain Neural Pathways.

Studies on rats suggest that during certain times in a child’s life more play may be essential to ease the “hyperactivity” that is a frequent diagnosis in children today (Henig, 2008). However, the field is missing critical research to determine if and how much more play during this time would actually be helpful for brain development. If that is the case, what might that insinuate for adults that have attention issues? What kind of play can we incorporate into a coaching model that will thusly meet a clients needs for development and imagination?

Categorizing the benefits of play from a research standpoint would be helpful for the field because there are also gaps in research about the implications of the shadow side of play. What about the violent nature of certain types of play? What do we learn from that?

Risky- Play

Different levels of play process can occur and sometimes co-cur but we don’t yet know the effects that they are having on the outcomes. When it comes to risk, we are going to have to

Children use play to develop and push their own boundaries. What is sometimes known as the dark side to play can also be absolutely essential to develop their own sense of boundary as they build an emotional landscape of themselves and the world. Studies are finding that adults that have not engaged in some form of risky play can be blind to their own possibility, having rarely pushed the limits of their boundaries.

Without risk, we are not growing. These rich experiences are what make up life AND what cause us to be engaged in our lives.

A coach can support a client in risky-play (whatever that might mean to them) which is essential in learning about their own boundaries. Coaches can debrief the experience afterward and explore what helped a client grow or if a new experience cause their client to want to discover a new piece of themselves. It’s important to explore those edges with their client.

Playfulness and Goal Attainment

In a culture ridden with goals and to-do lists itching to be crossed off, what is the role of play in achieving our goals?

A truly playful mind pursues only the goals that facilitate the enjoyment of the process rather than those that define consequences beyond the process (Xiangyou Sharon Shen, 2014).

The distinction between intrinsic and external motivation to finish a goal is critical to understanding how to use play to help a client reach their goals.

Intrinsic goals—“enhance the enjoyments of the process”—while external goals—such as money—can sometimes be a negative driving force. If the external rewards are imposed then the activity no longer feels like play and can cause stress. There is an outside factor that is motivating the client to follow a particular path.

Can incorporating playfulness lead to greater possibility of achieving goals? In a data-driven culture, I had hoped to find evidence that this is true. Unfortunately, I couldn’t find empirical evidence for this to be the case. However, understanding how a playful mindset could make a process more enjoyable.

As coaches assist clients in discovering a new way of doing things, it will be important to focus on the process as much as the final goal. Playing with this process will be where clients achieve their internal alignment.

Experiencing New Scenarios

Even as I write this article on the power of play, I see examples of play all around. Sitting in the Brooklyn Public Library, I’m watching an 18-month-old baby toddling through the vestibule. She gets just far enough to cause her mother panic and her mother breaks into a gallop to stop the little girl before she reaches the door. The little girl is precariously facing her mother with the largest one-tooth grin, arms wide, and giggling. She’s pushing her own limits (that happens when you’re just learning how your own feet work, I guess) and inviting her mother to join her. The simplicity the activity provokes complete and utter joy.

There is space in the coaching conversation to engage in play, or at least to debrief playful experiences throughout the coaching process. While dialogue is essential for a coaching relationship, it is not the only way that people learn about themselves and other modalities must be activated to encourage change that clients want to take.

We are evolutionarily wired to engage in play, to use play to help us adapt to situations that are new or unfamiliar, to create changes in our world that we want.

Bibliography

(n.d.).

Brown, S. (2009). Play. New York, NY, USA: Penguin.

Burghardt, G. M. (2010, Winter). The Comparative Reach of Play and Brain: Perspective, Evidence, and Implications. The Journal of Play , 348-355.

Henig, R. M. (2008, February 17). Taking Play Seriously . The New York Times Magazine .

Institute of Play - About. (2014, August 18). (S. o. Gallup, Producer, & Gallup) Retrieved August 14, 2014, from Institute of Play: http://www.instituteofplay.org/about/

Xiangyou Sharon Shen, G. C. (2014, Spring). Validating the Adult Playfulness Trait Scale (APTS): An Examination of Personality, Behavoir, Attitude, and Perception in the Nomological Network of Playfulness. Journal of Play , 346-369.