Research Paper By Heather Tingle

(Transformation Coach, CANADA)

One in five Canadians live with chronic pain; millions of Canadians deal with moderate to severe chronic pain, with consequences in every aspect of their lives (Canadian Pain Task Force, 2019). Persistent or chronic pain causes significant losses and costs to individuals, families, and communities; the economic costs alone of managing care for chronic pain in the public system in Canada has estimated at $7.2 billion annually (CPTF, 2019). Pain is not just about damage or injury to tissues; it is a complex, multi-faceted problem that is impacted by biological, psychological, and social factors. There is no quick fix for chronic pain. We are beginning to realize that the most successful treatments involve a multidisciplinary approach and respect the mind-body connection. Pain holds people back, and wherever people are feeling held back, there is a key place for coaching on the team. This paper will look at how chronic pain contributes to getting stuck in a pain-centered life, consider the relationship between pain and acceptance, and explore where coaching can interface with chronic pain, inviting a client to redefine normal and move toward a function-centered life.

Chronic Pain and the Pain Spiral

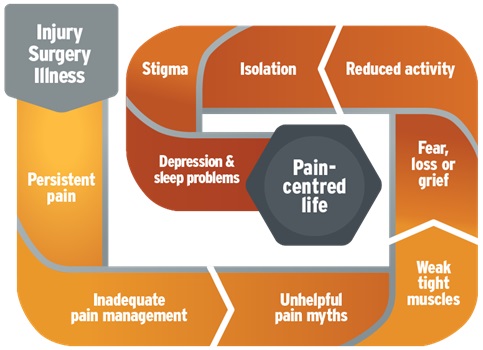

Humans are wired to pay attention to pain, at a “drop everything” level of response. Pain is an alarm bell that we interpret to mean injury, damage, danger, or wrongness. To get that urgent response, pain engages multiple pathways that involve not just the senses but also thinking and emotions (Kabat-Zinn, 2013 & Webmd, 2019). Pain is therefore endowed with multiple superpowers that monopolize focus. In acute pain (lasting less than about 3 months) this is helpful – we limit our activities to promote healing and prevent further injury while using our sensation of pain to gauge restoration. With many kinds of chronic or persistent pain (lasting greater than 3 months), however, there is generally minimal further healing left to occur. Pain messages are no longer serving a biological function, yet the alarm bells continue to ring, so we behave accordingly, limiting our behavior and thoughts. Due to the primal experience of pain, goals, and plans are more likely to be directed at self-preservation than growth, which then further contributes to pain, isolation, and exhaustion. Pain can become the central focus of life; this is the pain spiral (see Figure 1). You could imagine the spiral as a whirlpool, with the power to trap people in the exhausting and anxiety-provoking downward circular motion, hard to escape without outside help.

Figure 1: The Pain Spiral. The pain spiral: Moving from a pain-centered life to a function-centered life by F. Kirson, 2016.

The current thinking is that chronic pain is not caused solely by physical damage or incomplete healing. It is so much more complex, and we have much to learn, but the pain pathways are still being triggered in the nervous system despite the threat being minimized (PainBC & Buch, 2017). When chronic pain exists alongside another condition, it gets even more complicated. It is now understood that pain is not “just in your head”, meaning that we recognize it exists even if it cannot be objectively seen or easily measured. Paradoxically, pain is experienced in and by the brain (Brainman, 2019)where it is influenced by biological, social, and psychological factors. With our growing understanding of neuroplasticity (basically that the brain can change), this is good news, because it gives us a new route to treatment: our associations, thoughts, and emotions.

Pitfalls in a Pain-Centered Life

Chronic pain often has a pinpointed beginning, which divides a person’s life in two (‘before the pain began’ and ‘after the pain began’). It is a challenge moving forward while also dealing with grief over the loss of what life was like, and who one was, before the pain. If the medical experts are unable to determine why pain is occurring, it may lead to a long journey of further testing and experimenting with different medical or alternative treatments before getting what might feel like a vague diagnosis of chronic pain.

Kabat-Zinn (2013) and Buch (2017)note that challenges encountered by people experiencing chronic pain commonly include:

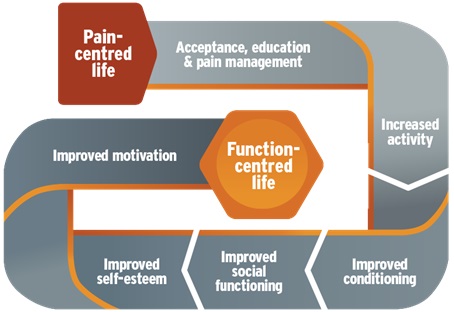

While the pain spiral in Figure 1 above may look like a linear path, it is more liken a spider’s web, with each component intimately connected to the others. Pull-on one string and you affect the others; this is both a pitfall and an opportunity for shifting out of the downward spiral of a pain-centered life, and into an upward spiral of a function-centered life (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Function-centered life. The pain spiral: Moving from a pain-centered to function-centered life by F. Kirson, 2016.

The Role of Acceptance

Our culture is steeped in the idea that physical and emotional pain should be avoided or fought. Fighting is an aggressive word – it means to combat or do battle, to put forth a determined effort to defeat or achieve something, or stop something happening(Merriam-Webster, 2020a). The thought of fighting brings up connotations of unwanted or unjust struggle and suffering. Acceptance seems gentler. It can mean receiving or taking on something willingly or to recognize as true or normal (Merriam-Webster, 2020b). It has a generally positive connotation and one could say there is an element of personal choice and power in acceptance of a concept or thing.

Yet when it comes to health and illness, in Western culture, the values of these concepts somehow become reversed. The idea of acceptance has been linked to giving up or losing (negative), while fighting has become the ideal and the expected, socially accepted course of action (positive). Fighting provides a simple (and therefore seemingly easier to measure) focus: defeat this thing. Acceptance can provide a scarier yet also empowering focus: live my best life alongside or despite the presence of this thing. This is the understanding of the concept of acceptance that we will use here.

The problem develops when the fighting attitude doesn’t help anymore. If chronic pain doesn’t seem to be going away, at what point does battling it becomes wasted energy? When does the search for “why?” become detrimental to progress? What if one gets so stuck in or so fused with the battle that one can’t see beyond the pain? That is the crux of the struggle of a pain-centered life. And that is exactly where coaching enters the game: with its focus on the present/future, observing, questioning, reframing and shifting thoughts and beliefs, and with a goal of empowering a client to live their best life.

Studies have consistently shown that the concept of acceptance of chronic pain is associated with less pain and lowered pain intensity, less disability, less depression, lowered pain-related anxiety, and better work status, among other things. (McCracken & Eccleston, 2003; Kabat-Zinn, 2013).

Interestingly, LaChapelle, Lavoie& Boudreau(2008) note that while their study participants rejected the word ‘acceptance’ itself, they “revealed that acceptance was a process of realizations and acknowledgments, including realizing that the pain was not normal and help was needed, receiving a diagnosis, acknowledging that there was no cure and realizing that they needed to redefine ‘normal’. (p. 201). It sounds like fertile ground for a coaching relationship to develop.

Coaching, the Pain Spiral, and Acceptance

Coaching, as a process, is ideally situated to facilitate a client’s growth out of the pain spiral (which may naturally move them toward acceptance even if acceptance isn’t a stated goal). In Figure 2, the function-centered life spiral shows acceptance as an early step, but moved out of the pain spiral doesn’t have to start with acceptance. To modify a metaphor often linked to coaching, pain can become the driver of the car instead of just being a passenger. It isn’t hard to imagine how much energy it would take just to keep the car on the road while pain is doing the driving. Finding ways to shift that energy and reclaim the active role moves a chronic pain sufferer out of the pain spiral and into the driver’s seat. Acceptance can come later.

Some of the ways a coach can help a client break out of the pain spiral are by:

Specific Applications to Coaching People with Chronic Pain

Buch (2017) states that many patients with chronic pain hide their pain or their thoughts about pain because of fear of judgment, or fear of how it might impact their relationships. Interacting with a nonjudgmental witness (coach) might be something a client has not encountered anywhere else and that alone can be of immense benefit. Few types of practitioners can really sit with a client in their lived experience while being separate from any other role or expectations of treatment.

With so many losses, and when comparing themselves to their pre-pain selves, patients often lose sight of how their strengths can be applied in their new life. The stories of their past have lost relevance to the present; they may never be able to regain functions or skills their pre-pain selves had. Tools like values statements and the Health Wheel can be a safe place to start, as they can provide the client with a big picture view and suggest direction and priorities, e.g.: “What do you notice about your health wheel?”; “Where shall we start?”.

Consider questions like:

“What are you noticing in your body when the pain flares?” and

“What are you noticing about your thoughts during those times?” and

“How do those thoughts impact __ on your health wheel?” or

“How could you reframe those thoughts to be more kind/helpful/__ to yourself at that moment?”

A specific visualization concept is known as the ‘Energy Bank’ resonates with many people who experience chronic pain – we all have energy limits but people in the pain spiral bump up against those limits before most people, and way before they want to. Visualizing energy as a finite yet replenishable resource (much like money in the bank, or water in the well) is a useful exercise. The energy bank concept provides a metaphor that helps focus energy use in ways that will move them forward. And reminds them of the value of considering what replenishes the bank. Just like money, energy won’t magically appear in the account.

There is a special place for a blended coaching/mentoring approach for people experiencing chronic pain. Kabat-Zinn notes that tuning into a pain sensation is more useful in pain relief than distraction (2013); this is counter-intuitive and many clients might not otherwise notice this without the assistance of a knowledgeable mentor/coach who can shine a light into those dark corners. Skills in mindfulness are paramount here. Chronic pain causes a lot of fear – for example, fear of further pain or embarrassment- significantly powerful enough to change behavior despite the uncertainty that they would even happen. Coaches play a role in helping people face fears by co-devising experiments that gently explore their limitations and how best to manage them. Clients may need some guidance from a practitioner with a deep understanding of pain in developing appropriate experiments. Therapy, too, might be useful alongside or prior to coaching if the past or other deep trauma is interfering in moving forward.

Routes to Acceptance: Observations from coaching people with chronic pain

It has been my privilege to accompany several clients on their journeys out of a pain-centered life and into a function-centered life. Along the way, I have noticed that this process is unique to the individual and often acceptance comes in by the back door, without ever being directly sought. Here are a few summaries to illustrate how various the routes can be (real names not used):

Amal sought to coach with the idea of defeating pain so she could resume work. She actively rejected and fought acceptance because to her it was equivalent to laziness and giving in. When she noticed that this fight left her no energy to work towards what she valued, she began to redefine her relationship with pain, what acceptance meant, and what her new normal might look like.

Bob discovered that by acknowledging the physical presence of pain, noticing how he experienced it, and allowing his support network to contribute, he gained greater control over his pain. He took actions to pre-empt the emotional fall-out and found he had energy left to put into what he wanted to accomplish.

Cindy quickly discovered that simple acknowledgment of what she accomplished each day gave her a measure of control over the pain and pushed it to the backseat. This realization reconnected her to a more positive self-image and disconnected her from her pre-pain expectations.

Diego requested coaching because he was having trouble making decisions. He is still in the limbo land of incomplete diagnosis and developing treatment plans. Through coaching, he has started to reframe what ifs’ and reconnect to his own power, which helped him put energy into the process now rather than spraying it into the unknown future.

Euna sought to coach to have someone alongside her that could act as a sounding board and help her structure what she wanted to try into a concrete action plan.

Conclusion

Chronic pain is an immense problem in our society, and it limits the hearts, minds, and bodies of millions of people. As a process that encourages new realizations and acknowledgments, coaching is well-suited to be part of the multidisciplinary tool kit for the treatment of chronic pain. Nonjudgmental witnessing, co-designing experiments to move past fear and gain confidence in a new reality, and acknowledgment are just some of the key functions of coaches that facilitate movement out of a pain-centered life. Coached clients may naturally move toward acceptance of their pain, and the benefits that carry, without ever using that word. Lessons from chronic pain can extend to any coaching client, where the goal is to define a new normal: a new world shifted from what was previously being lived.

References

Canadian Pain Task Force. (2019). Chronic pain in Canada: laying a foundation for action. Retrieved from: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/corporate/about-health-canada/public-engagement/external-advisory-bodies/canadian-pain-task-force/report-2019.html

Kabat-Zinn, J. (2013). Full catastrophe living: Using the wisdom of your body and mind to face stress, pain, and illness. New York: Bantam Books.

Kirson, F. (2016). The pain spiral: moving from a pain-centered to a function-centered life. Retrieved from: https://www.liveplanbe.ca/pain-education/pain-basics/the-pain-spiral-moving-from-a-pain-centred-to-a-function-centred-life

Pain BC (Producer), & Buch, W. (2017). Chronic pain and mental health [Podcast] Retrieved from https://www.liveplanbe.ca/pain-education/anxiety/chronic-pain-mental-health-with-dr-wesley-buch-rpsych

Brainman. (2014, Oct 2). Understanding pain in less than 5 minutes. Retrieved from [Video File] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5KrUL8tOaQs&feature=emb_title

Merriam-Webster. (2020a). Fight: Verb. Retrieved from https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/fight

Merriam-Webster. (2020b). Accept the Verb. Retrieved from https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/accept

McCracken, L. & Eccleston, C. (2003). Coping or acceptance: What to do about chronic pain? Pain, 105(1-2), 197-204.

LaChapelle, D., Lavoie, S. & Boudreau, A. (2008). The meaning and process of pain acceptance. Pain Research and Management, 13(3), 201-210. https://dx.doi.org/10.1155%2F2008%2F258542