Research Paper By Gaya Gamhewage

Research Paper By Gaya Gamhewage

(Executive Coach, SWITZERLAND)

Executive Summary

Coaching is a helping profession that draws and must continue to draw from a wide range of other disciplines. My own coaching journey brought into focus the intersection between coaching, neuroscience, and spirituality – especially Buddhism. Drawing on my medical training and Buddhist backgrounds, I wanted to seek out the scientific evidence for integrating selected Buddhist practices into my coaching practice.

We are experiencing a golden age of neuroscience with unprecedented amounts of research and interest in neuroscience reveal how our behaviors, feelings, and experiences are “wired” in our brains and affect our mind. The structure and physiology of our nervous system clearly affect us in profound ways.

I followed a qualitative research methodology and posed for myself three research questions: what evidence can be found in neuroscience (in 2020) for the use of Buddhist teachings that are relevant for coaching?; what evidence-based Buddhist practices can therefore be confidently recommended for coaching?; and what cautions and recommendations can be made in the integration of Buddhist ideas into modern-coaching?

My own coaching model – the WISDOM Model; and my Coaching Power Tool – From Expectations to Exploration are both strongly integrate modern coaching principles in Buddhist teachings. This research adds a deeper layer to those and explores the neuroscientific basis – brain structure and brain physiology – that is now, 2,600 years after the life of the Buddha, finally providing scientific evidence to Buddhist Concepts and Practices. The research is laid out to introduce the reader to Buddhist teachings and their alignment with modern-day coaching; summarize the latest in a fast-growing body of neuroscientific evidence that relates to coaching and Buddhism; select and analyze Buddhist practices and concepts relevant to coaching that is backed by neuroscience, and make recommendations for the future.

We now have evidence for how our brains have evolved, and can better explain the link between the brain and the mind. Much of the neuroscience available today that is relevant for coaching, emotional intelligence, and personal development have been generated by the curiosity of western psychologists and scientists who have been exposed to or themselves practiced Buddhist techniques like meditation.

Neural activity in two small almond-sized structures in our brains – the Amygdalae, which is thought to be evolved from the mammalian brain, is now clearly linked to the processing of emotions. When they are triggered, by real or perceived threats, the amygdale “hijack” the executive center of our brain that is usually responsible for rational thought. This leads to speech and behaviors that are reactive (often with negative consequences). This automated neural and biochemical reaction can lead to unhappiness, stress, anxiety, anger, suffering, and can be presented as the starter problem that clients bring to coaching.

Coaching is one way of helping clients recognize quickly and disarm the Amygdala Hijack restoring the ability to respond wisely instead of reacting instinctively. Our brains are created for our survival. We have to work hard, including through coaching and spirituality to achieve happiness.

Luckily, neuroscience also provides strong evidence that our brains are neuroplastic – they can change structurally and chemically. Thoughts, speech, or actions must be repeated (between 21 and 45 times according to available research) to create new patterns of thought, speech, or behavior. This provides the potential for us to change, develop, create new habits, and to progress to reaching our full potential.

These two findings which are aligned with coaching practice also provide neuroscience support for Buddhist teachings, here more specifically about the truth of the common human condition of suffering or satisfactoriness; as well as the truth that suffering can be ended by following a certain path (which works on the principle of neuroplasticity).

Two types of ideas come directly from a Buddhist teaching that is used today in coaching and has promise for offering more to the profession and our clients. Buddhist teachings focus on the mind – the person, and not the story of the client – and therefore the link between neuroscience, psychology, and Buddhism offers great insight, resources, and concepts that can be used in coaching.

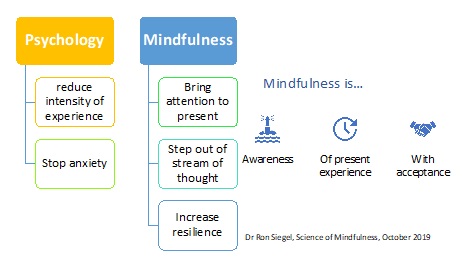

The first is meditation, and there is neuroscientific evidence for how they support self-development and can be applied in the coaching profession. Mindfulness meditation (or more commonly practiced as breath meditation) invokes a feeling of being in more control, strengthens resilience to external and internal crises and stressors, induces mood and emotional stability, increases attention and focus, and allows us to be present at the moment. The effects described here are dose-dependent. That means the more you practice it, the more the effects. The effects also appear to be mutually reinforcing.

The second Buddhist origin practice with sufficient neuroscientific evidence to back its use in life and coaching is Loving-kindness meditation (LKM). The evidence shows that even small doses of LKM (as little as 7 minutes a day) increases empathetic concern, activates the neural circuits for feeling good and for love, and even prepares a person not only to feel compassion for the suffering of others but prepares them for acting to help others based on that compassion. Importantly LKM reduces unconscious bias (as little as a total of 16 hours) and helps to control the ego. LKM leads to empathy, self-compassion, and a more positive connection with others.

The third set of resources to draw on are Buddhist values and core ideas. These include the four immeasurable states for which neuroscience provides a scientific basis in brain structure and brain chemicals. Both these can be changed (neuroplasticity) with persistent repeated Buddhist-inspired practices of four core qualities of the mind from occasional states to boundless and immeasurable states: loving-kindness – caring for the wellbeing of self and others; compassion – being moved by others’ suffering and motivated to help; sympathetic joy – happiness at the success of others; and equanimity – the even keel and emotional and cognitive stability regardless of external events, the 8 vicissitudes of life: gain and loss; fame and anonymity; praise and blame; pleasure and pain.

There is evidence that mindfulness meditation and loving-kindness meditation support the development of these states of mind and also change brain structure and chemistry.

These four mental states that correspond to Buddhist Emotional Intelligence are further supported and reinforced by the 10 Buddhist qualities to cultivate throughout life: generosity (even talking about acts of generosity change brain chemicals and activity); virtuous behavior (universal moral standards); wisdom (insight gained from meditation); patience ( the prefrontal cortex is engaged and amygdala and other stress structures are disabled); energy; determination (both related to volitional activity or intention); truthfulness; renunciation (to reduce too much attachment to external objects and situations)and kindness and equanimity overlapping with the four mind states above. The Noble 8 fold path corresponds to the hard work that is required, in different aspects of one’s life, to achieve one’s fullest potential.

These findings and analysis can be used to further elaborate coaching models, used to delve deeper into and build competencies for emotional intelligence and spiritual intelligence, and has a great deal to offer for transformational coaching. Incorporating these concepts into the mainstream coaching profession will address better the needs of clients, stated and hidden, and make every coaching session transformative (not transactional), and help build the competencies of coaches whose own life journey will be enriched by this added dimension. Using a neuroscientific approach to coaching will increase the credibility and respect for coaches and can only push our profession into the future. Using science-based spiritual techniques (in the correct way by qualified teachers) as those presented from Buddhism here will help weed out non-evidence-based practices that could bring disrepute to the profession.

Recommendations based on this research are

- Incorporate spiritual frameworks that are science-based into coaching training programs

- Insist that spiritual techniques supported by science such as meditation, and techniques for developing qualities such as compassion, are taught according to a standardized curriculum and not left to the whims of unqualified teachers.

- Consider integrating modules on meditation and compassion into the ICA curriculum as online classes, labs, or using other techniques

- Commission high-quality research on spiritual intelligence and its application into different areas of coaching (personal coach, executive coach, team coach, etc) to grow the body of knowledge and create new evidence

Part 1: Introduction

1. Motivation and rationale

I am a medical doctor by training and a public health expert. For the past 20 years, I have focussed on training, learning, and capacity building of individuals and countries. I am also a Buddhist who is experiencing an intensification of my practice of the tradition. As a coach, I have been both fascinated and inspired by how science and spirituality interface with the helping professions. A helping profession is defined as one that nurtures the growth of or addresses the problems of a person’s physical, psychological, intellectual, emotional, or spiritual well-being, including medicine, nursing, psychotherapy, psychological counseling, social work, education, life coaching, and ministry[i]. I have spent my entire life in helping professions as a doctor, teacher, and now as a coach

The learning pathway to becoming a coach has also exposed me to be coached. My biggest learning of the past year has been the need and a deep urge to align my professional self (doctor, health expert, and teacher, coach) with my spiritual self. This alignment is very important to me and I believe will help me evolve into my best self in the many roles I will continue to play in life.

Therefore I was inspired to bring science, spirituality, and coaching into one framework. During my time training to be a coach, I was surprised by how mainstream Buddhist ideas seem to have become. Presence, compassion, mindfulness, meditation are buzzwords commonplace in modern-day coaching, albeit with a wide range of interpretations. Emotional Intelligence and spiritual intelligence which draw in part on Buddhist thinking are increasingly influencing coaching. Some have even infiltrated the training curriculum for coaches. Core ideas of coaching, such as the client have the power and ability to solve their problems; coaching the person and not the story; being present for the client; supporting self-awareness and mindfulness in the client; many aspects of emotional intelligence; and not judging can be directly linked to the core teachings of the Buddha.

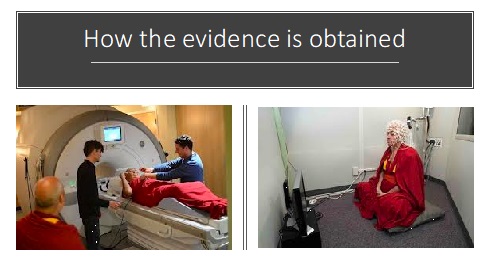

My coaching journey also coincides with great advances in science and medicine. Since 1992 when functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) was first used to map activity in the human brain there has been a great leap forward in the field of neuroscience. Some liken it to the discovery of the microscope in 1725. Others see it as significant as the mapping of the human genome in 2001. The application of new knowledge in neuroscience is now extending well beyond medicine and beginning to influence psychology, education, personal and leadership development, and coaching. The recent explosion in knowledge about the brain – which is estimated to have roughly doubled in just the past twenty years – also offers many practical possibilities, including relieving distress and dysfunction, improving wellbeing, and deepening religious or spiritual practice. Anything that explains or gives insight into the human mind and behavior has great potential for the practice of coaching.

This is also a golden age for research – both neuroscientific and on meditation and other Buddhist practices. The book, Altered States, by Daniel Goleman Ph.D. (Scientific writer, author, psychologist, and world-renowned emotional intelligence with experts) and Richard J Davidson, Ph.D. (Professor of Psychology and Psychiatry at the University of Wisconsin-Madison directing their brain lab, and founder of the Center of Healthy Minds), highlights the notable acceleration in scientific articles on meditation. In the 1970s when the two started publishing research on meditation, there were just a handful of scientific papers on meditation. There were more than 100 randomized trials (the most rigorous way to prove scientific facts) by 2014, more than 6,000 studies on mindfulness by 2018.

My own desk review indicates that this number has grown much further in the past three years. As a researcher part of online research platforms (Academia.edu and ResearchGate.net), I usually receive at least one notification per week on peer-reviewed papers on various aspects of meditation and Buddhism.

But I also see how these core and human values and concepts from Buddhism are also misused, misinterpreted, and commercialized in the wellness and helping professions. Applied without a robust framework and without drawing on the growing body of scientific evidence, the integration of these “New Age” ideas could negatively affect the credibility of the coaching profession. Whenever possible, as a profession, we must favor evidence-based practice in our work.

This research paper is the result of my search for the alignment between science, spirituality, and coaching (and more broadly the helping professions). It clarifies for me my path forward as an authentic person and a coach and I hope it offers insight and inspiration for others, while at the same time providing a scientific base for my assumptions, approach, and recommendations.

2. The Scope

This research focused on the integration of science, spirituality with coaching. In the paper, I look most closely at neuroscience (for the science domain) and Buddhism (for the spirituality domain). These specific fields are chosen because I have a background and a deep personal and professional interest in both. I think that the research could equally inform other helping professions such as medicine, nursing, psychotherapy, teaching, people who help with addictions, stress, anger, workplace or family conflict, and relationship challenges.

Figure 1: Scope of the research paper

Figure 1: Scope of the research paper

Psychologist, meditation practitioner, and author Rick Hanson, Ph.D., in his 2010 Wise Brain Bulletin, referred to the interface between psychotherapy, neurology, and contemplative practice. In his many subsequent publications, he draws from neuroscience and Buddhist practice. I have been inspired by his work and draw on some of his talks and publications in this paper. The reference section has a fuller list of contemporary experts and publications I have drawn from in the past year that bring neuroscience and Buddhism to the vast and unchartered field of wellbeing and happiness. In the coaching domain, I draw from several publications including The Twenty-one skills of Spiritual Intelligence, by Cindy Wigglesworth. In her book, she sees spiritual intelligence as a set of skills that collectively help us transcend our “smaller nature” and growing into our full potential as human beings – very similar to mainstream coaching. In the field of personal fulfillment. Abraham Maslow described this as “a single ultimate goal for mankind, a far goal toward which all persons strive ..which amounts to realizing the potentialities of the person, that is to say, become fully human.”

3. Research questions

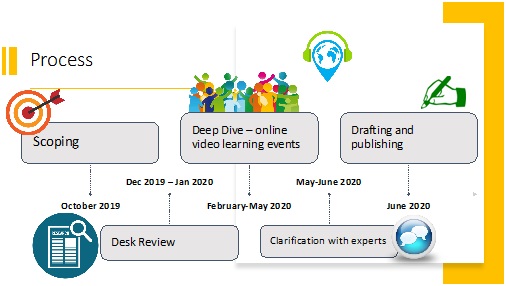

4. Methodology

I used qualitative research methodology for this paper. I started with a desk review methodology over a period of four months. I drew on secondary data that were from peer-reviewed journals, publications, books, grey literature, and websites (both hard copy and online versions) that referenced peer-reviewed publications, talks from renowned experts on the internet, and translations of Buddhist teachings in the Wisdom Publications series edited by the renowned Buddhist scholar-monk Bikkhu Bodhi. I attended several online pieces of training and webinars to better understand the key information and their implications relevant to coaching, neuroscience, and Buddhism. I interviewed the President and Chief Resident Monk of the International Buddhist Foundation in Geneva, Switzerland Venerable Halyale Wimalratne, to clarify key points in Buddhist teachings and reflected with him on how they are used in modern society.

Next, I packaged some of the key ideas that emerged as most relevant to coaching into 3 information sessions and conducted free interactive webinars to gather feedback from a group of 50 people who were drawn from Buddhists and non-Buddhists (Christians, Muslims, atheists, and agnostics). Each package focussed on a single topic which

The webinars, conducted through Zoom technology and were conducted on Friday evenings from 18:00-17:90H CET, during the COVID19 pandemic lockdown. The topics covered, one per week were: Managing anxiety; Kindness and compassion; Is your mind getting in your way?; How resilient are you?

Next, I used my own empirical data – observations and experience as a coach during the past year during my enrolment in coach training and the video learning events, to analyze and make sense of the findings.

Figure 2: Methodology and process

Part II: Buddhism& Coaching

1. The Foundation

Buddhism is a non-theistic world religion based on the teachings of the Gautama Buddha who lived 2,600 years ago in India. It does not focus on a creator God and posits that people are responsible for their own lives, their own happiness, and their liberation. It invites all individuals to come and experience for themselves the result of the application of teaching (called the Dhamma in the ancient Pali language spoken by the Buddha). The teaching focuses on the 4 Noble Truths that form the foundation of his teachings. He laid them out like a doctor or physician would – diagnosis, etiology, prognosis, and treatment.

The Buddha observed through his own life experience and through insight he gained during mediation that everything in the known universe is in a state of constant flux and change. He was not divine and was a human finding a path to happiness that any other human could also adopt. Buddhist teachings describe the qualities of the teaching or Dhamma: as

The teachings of the Buddha are consistently clear about two things: that the motivation, effort, and work of developing yourself must come from you; and at the same time, he describes that all of the spiritual paths is greatly helped by Noble Friends who helps you along the way. These Noble Friends help keep you on track, offer themselves as a mirror so that you can see what you are really thinking, saying, and doing; ask you the right questions to make sure you are aware of your behavior; challenge you when you need it, and celebrate your success with you. All of these are much like a coach in the modern-day world.

Link to coaching: This is a training or development path designed by an accomplished person that any motivated person can follow to attain fulfillment and happiness. The teachings are to be experienced for people by themselves (no one can help you but yourself, but Noble friends ( a coach) can support you. No belief is required.No divine punishment or absolution awaits. It is in your own hands and achieved through your own efforts.

Fundamental to the teachings is the Buddha’s description of what he called the three universal characteristics of the world. The first is the universal concept of impermanence. From atoms to life forms, to stars and galaxies, all matter is constantly changing. This observation is increasingly supported by the massive progress in the world of physics, biology, chemistry, medicine, neuroscience, astronomy, and other hard sciences.

The second characteristic that hypothesizes (as this cannot be proven from the perspective of one life) is no unchanging personal soul as we are constantly in flux and that our mental state or soul changes immeasurable times in our lifetime. The number of brain states possible in a human (see the section on neurology below) exceeds the number of estimated particles in the universe. This means our minds are most likely to be a continuous flux of brain states rather than one fixed never-changing entity.

The third universal characteristic is also derived from the concept of impermanence. Suffering, dissatisfaction, stress, and frustration are apparent and obvious in our lives. This means that it is an illusion (or delusion) to think that things and people will remain unchanged. When things we like change, we are unhappy and dissatisfied. Lovers fall out of love. Friends become enemies. We lose lives to illness and death. Youth changes into old age. We lose wealth, status, property. The “ordinary” person does not “see” these characteristics and therefore is in a perpetual cycle of unhappiness or frustration. They attribute their dissatisfaction to the world (external environment or other people). But the core problem is not understanding the impermanence of all conditioned phenomena (material things as well as objects of the mind such as perceptions, thoughts, emotions, views, opinions, expectations, imagination, etc).

Link to coaching: Clients often seek coaching to address unhappiness, frustration, dissatisfaction with their own lives, their environments, or the people in their life. Much of this unhappiness is attributed by the client to the outside world of the client, but in reality, it should be directed inwards- This is consistent with the coaching concept of “coach the client (internal world); not the story (the external world).

Note: My coaching power tool – from Expectation to Exploration” – further explores this issue.

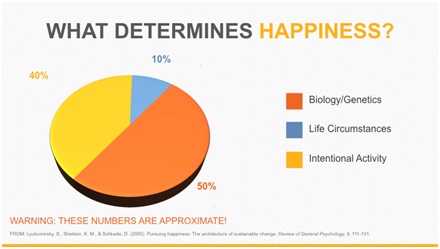

2. Role of intention (volition)

Buddhist teachings are based on the concept of Karma as a universal law. Karma is the cause and effect of volitional (or intentional) acts of mind, body, or speech. Unlike its use in pop culture, Buddhism includes good and bad in the concept of karma. Like Newton’s third law which states that for every action (or force) in nature there is an equal and opposite reaction. Karma is the name given to intentional or volitional actions by sentient beings and these actions include actions of the mind (thoughts, emotional states, views, wishes); actions by the body, and action through speech. Each of these, as long as it is intentional, creates a reaction (now or in the future).

Figure 3:2005 paper by researchers Sonja Lyubomirsky, Kennon M. Sheldon, and David Schkade

Figure 3:2005 paper by researchers Sonja Lyubomirsky, Kennon M. Sheldon, and David Schkade

This again circles back to the idea that our happiness and suffering are our own responsibility, and we ourselves alone are responsible for our lives. Each person is an inheritor of their karma, and their karma will follow them always. We are currently experiencing the fruits of past karma (good and bad). And in each moment, we are creating karma for the future. Our karmic bank balance at any moment influences how our lives are. And like a bank account, we can either make a deposit or make a withdrawal. The effects of karma can be experienced immediately, or delayed later in life, or even in another life. Buddhism recommends that we actively use our effort to multiply actions of mind, body, and speech that increase our karma, do things that bring new good karma; try to eliminate actions that bring bad karma; and resist actions that can generate new bad karma.

Note: But Buddhism does not attribute everything that we experience is Karma. Karma forms part of what we experience. What we and the world experience can also be due to universal physical, biological and other laws. Skillful actions of mind, body, and speech lead to good karma and unskilful actions lead to good karma.

Link to Coaching: empowerment of the individual, personal responsibility for one’s life and happiness, not blaming others or circumstance, freedom from divine or supernatural power that controls one’s life, ability to change the trajectory and the experience of one’s life for the better with the intentional activity of the mind, body, and speech. Recognizing that the mind, as well as body and speech, have to be observed and managed to develop ourselves. Being proactive, living life with intention and awareness of the possible repercussions – good and bad – of all volitional activities of mind, body, and speech. The concept of skillful and unskilful indicate that good or useful actions can be developed by ourselves and further reiterate the nature of teaching as a personal development pathway akin to coaching.

3. A Buddhist approach to Personal development

The Eight-Fold Path is a personal training or development plan for a life of happiness and ultimate fulfillment and liberation (from suffering) from 26 centuries ago but still practiced today. It is called Noble because it leads to real happiness, whereas other (ordinary) paths may lead to suffering.

Right, Understanding refers to understanding the three characteristics, the 4 Noble Truths and the 8 Fold Path described above, as well as a degree of confidence and curiosity in the teachings. Confidence is important as it provides the initial fuel to embark on the Path. Curiosity supports the effort that will be needed. As the Path is practiced and “realized” confidence will be replaced by right understanding through wisdom.

Right Thoughts (also translated as intention) refers to thoughts and intentions to reduce and gradually eliminate: attachment (because attachment leads to suffering); harm to others or self; anger ( replacing it incrementally with kindness and compassion to self, others, and the environment)

Right Actions refer to respecting and protecting others – not killing living beings, not stealing in any manner or form, not indulging in sexual exploitation, abuse, or adultery; and not taking drugs or alcohol that can cloud the mind.

Right speech refers to not harming others with speech – not lying, not using unpleasant speech, on using speech that divides people or creates conflict (including gossip), and not wasting time on useless or meaningless conversations

Right livelihood is described as taking up jobs and careers that do not harm others such as killing or butchering, trade-in weapons, toxic substances, and prostitution, slavery, and human trafficking are all considered the wrong livelihood. In a more subtle sense, cheating, deceiving, and harming others are the opposite of right livelihood.

Right effort means being proactive, determined, and using one’s energy for generating, cultivating, and maintaining volitional acts of mind, body, and speech that lead to good karma; and being alert for, preventing, diminishing and eliminating those leading to bad karma

Right mindfulness refers to being aware of the present moment and paying attention to ourselves, others, and the world around us. It can be practiced through different types of meditation and throughout our normal daily lives.

Right concentration means further developing meditative skills to go beyond paying attention to developing wisdom and insight into the nature of our own minds and the world.

Link to coaching: Personal development with the client in the driving seat is the heart of coaching as it is in Buddhist training. The development process is seen as incremental, life long, long term, and self-paced in both domains. Meditation and mindfulness are core practices. Both embrace mutually reinforcing actions in the areas of wisdom, conduct, and discipline. Secular Buddhism is more directly applicable to coaching as it looks at the teaching in terms of practice without buying into the metaphysical concepts involved in the mechanics of karma or rebirth, and other planes of existence (which will not be elaborated here).

4. Buddhism and Emotional Intelligence

Buddhism advocates a life-long practice to become self-aware, manage oneself, understand, and live happily with others, which are the core elements of Emotional Intelligence as described by science journalist, psychotherapist, and author Daniel Goleman. Early in his career, Goleman[iii] studied in India and Sri Lanka and was influenced by Buddhist thinking. His first book, now called The Meditative Mind, summarizing his research on meditation.

The Buddha describes four immeasurable mind states that should be cultivated for the happiness of self and others, which are well-aligned with concepts of Emotional Intelligence in the modern-day. These are called “immeasurable” because the goal is to have these mindsets that persist over our lifetimes, is extended to everyone without exception, and they become the default position of the mind as one progresses along the Noble Eightfold path. For most of us, we experience them intermittently but we have not trained our minds to expand them as a state we can sustain over time and in any situation. They are described below.

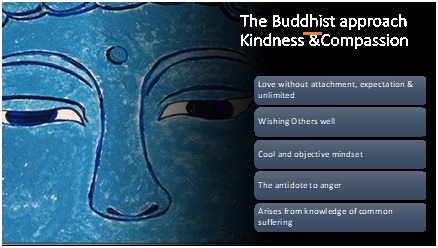

The first is Loving-kindness or Metta is the ability to feel connected enough to another person, or any living being for that matter – with goodwill and thoughts of non-harm. This creates a feeling of deep connectedness that is a basic human need. Humans need it as much as we need food and water. It is just not limited to acts of kindness but is a viewpoint and perspective that must permeate all that we think, say, and do about ourselves and others. It enriches both the person who shows kindness and the person who receives it. It should not be confused with its selfish attachment. It is selfless. It is the timeless, most powerful antidote to anger, hatred, and cruelty.

The second is compassion or Karuna– the quality of the human heart to be moved when witnessing the suffering of others. This is what across belief systems spurs us to lend a helping hand to acknowledge and alleviate the suffering of others. It is not the same as pity which puts you on a higher pedestal than others. It is helped by empathy – the ability to put yourself in the shoes and lives of others and understand their suffering from their point of view without judgment. This is the antidote to cruelty and selfishness.

The third is where Buddhists are advised to dwell is sympathetic Joy or Muditha. This is the ability to be truly happy for the fortune, luck, success, and happiness of others, with no comparison with oneself. It is the only antidote to jealously, resentment and egocentrism, and all the terrible things that lead from them.

The fourth is the quality of equanimity. This means keeping a balanced mind and to be able to face anything life throws at you with equal calm. The Buddha recognized that everyone is subject to four pairs of opposing vicissitudes in life:

Anyone alive faces these in different combinations. As the true nature of life is constant change, everyone will experience these eight conditions repeatedly. Therefore learning to have equanimity is a wise and useful way to face life. It should not be confused with indifference. It is the antidote to clinging and attachment.

These four are timeless, universal human emotional states that can create universal brotherhood towards the positive and wise goals that humanity sets for itself. The core part of Buddhist training is to appreciate and apply these consistently and continuously in our lives.

Link to coaching: The 4 immeasurable states are closely linked to emotional intelligence, and allow for the understanding of self and others for the client and coach. For the coach, these are 4 essential mental states to cultivate to fulfill the role of the coach – attend and be present for the client with kindness and love; have compassion for the client; celebrate the successes of the client and be stable and unshaken when life’s vicissitudes are experienced. Also, linking to the impermeant nature of things and experiences, and the knowledge that all the 8 vicissitudes of life happen to everyone all through their lives, can bring a shift in perspective that allows the client to reframe how their see their problem and create more realistic solutions for themselves.

5. The qualities to perfect throughout life

These qualities are a reformulation of the basic teachings. It is the advice given to any person to have a fulfilled life and at the same time develop spiritually.

Generosity (dana) – is the ability to share owns material wealth and possessions, one’s wisdom and knowledge. It helps develop detachment and grow kindness and compassion.

Moral conduct (sila) – is virtual behavior that does not harm self or others and creates a peaceful and mutually supportive environment within the family, at work, and in society at large. The discipline required for this is based on caring for self, for others, and the environment.

Renunciation (nekkhamma): is becoming free from enslavement to the sense organs and the mind. To be able to respond instead of reacting to triggers and stimuli. It is sometimes understood also as living a simple life without too many attachments to things, people or ideas, while at the same time caring for the well-being of self and the world.

Wisdom (paññā): is the ability to see things as they really are, and differentiate what is real from what is perception. It is both the driver and the result of following the Path.

Energy (viriya): is the internal energy that one must generate to be able to follow the self-development journey, to watch one’s volitional or intentions actions of the mind, body, or speech.

Patience (khanti): is the ability to react with consideration to challenging situations, and not to lash out in unskilful ways. (Skilful actions are those that lead to good karma, and unskilful actions lead to bad karma).

Truthfulness (Sacca): this is the quality of always telling the truth, always acting by the truth, and always supporting the truth.

Determination (adhitthana): is the ability to set intentions and goals for oneself and pursue them regardless of the difficulties one faces.

Loving-kindness (metta): this is the ability to have unconditional platonic love and kindness to others and self. It is the antidote to ill will, anger, aversion, and conflict.

Equanimity (upekkha): The ability to stay unfazed in the face of the eight worldly conditions or winds of life: gain and loss, fame and disrepute; praise and blame; happiness and suffering.

In a similar vein, in Greco-Roman traditions qualities such as integrity, kindness, patience, and humility were considered keys to enduring wellbeing. Both western and Asian traditions seemed to value virtue as part of the positive transformation of the person. In Buddhism, this is known as “inner flourishing” or being the “the very best within oneself”.

Links to coaching: All these 10 qualities are of relevance for the coach, the client, and the coaching relationship and process. All of them relate to self and others. For example, the coach must always be generous, be kind, have patience, have equanimity, and be truthful. With the coach’s support, the client can start developing awareness and building skills to be more compassionate to self and others, learn patience and equanimity to respond with wisdom and not react; develop the determination to set goals for themselves and follow-through, and find the energy that is required for the changes they want to make in their lives. The moral behaviors or virtues mentioned here are mostly common to all belief systems and are manifested in the behavior of the coach and the client. Again, the Buddhist idea of inner flourishing” or being the “the very best within oneself” is consistent with the aim of coaching.

6. Spiritual Intelligence

Cindy Wigglesworth, a renowned personal development expert, author, and public speaker has developed a competency-based spiritual intelligence assessment tool- the SQ20. Beyond religious and cultural differences, Wigglesworth describes a congruity of ideas about what human attainment looks like. The most frequent descriptors of such high human achievement include: has authenticity and integrity; is calm, peaceful and centered; has clear mission or vocation; is compassionate, caring, kind and loving; is courageous, dependable, faithful and faith-filled; is forgiving and generous; is a great teacher, mentor, leader; is humble, inspiring and wise; is non-violence; open-mindedness and open-heartedness; and is persistent, values-driven, and committed to serving others.

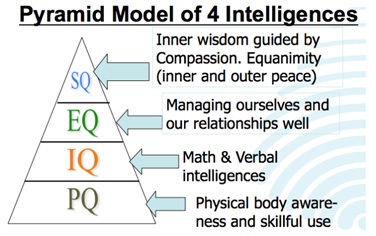

Figure 5: Situating spiritual intelligence with other intelligence – C.Wigglesworth

Figure 5: Situating spiritual intelligence with other intelligence – C.Wigglesworth

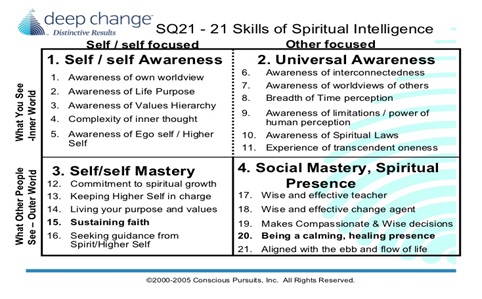

While emotional intelligence is now widely accepted as a set of core skills for coaches and their clients. But spiritual intelligence is less so. The word spiritual often conjures up the idea of religion, while people can be spiritual without being religious. The definition used here is that of Wigglesworth’s: Spiritual intelligence is the ability to behave with wisdom and compassion, while maintaining inner and outer peace (equivalent to resilience in Buddhist teachings), regardless of circumstances. The 21 skills she proposes for SQ are given below

Figure 6: 21 skills of spiritual intelligence; C. Wigglesworth

Figure 6: 21 skills of spiritual intelligence; C. Wigglesworth

Link to coaching: A coach supports the client to reach their highest potential and the concept of spiritual intelligence is very much part of that goal. It has the same 4 components as Emotional Intelligence, which is widely used in coaching today. The following are all domains of EQ (and SQ equivalents are in brackets).

But SQ takes this several steps deeper touching directly on underlying issues that coaching seeks to bring to the surface to support the client gain more awareness and mastery. These fall in the domains of our understanding of how we fit into the world, values, and beliefs that drive us, the meaning we attach to events and situations, and of course answering to your higher self, and/or seeking guidance from spiritual power. The model also places at its heart compassion, kindness, and wisdom. All these are directly related to coaching and align perfectly with Buddhist teachings. They have the ability to believe utility to the client and have the potential to deepen the competencies of the coach.

Part III: Neuroscience& Coaching

Refers[iv] to any or all of the sciences, such as neurochemistry and experimental psychology, which deal with the structure or function of the nervous system and brain. It is the study of how the nervous system develops, its structure, and what it does. Neuroscientists focus on the brain and its impact on behavior and cognitive functions. It is an interdisciplinary science that works closely with other disciplines, such as mathematics, linguistics, engineering, computer science, chemistry, philosophy, psychology, and medicine. It is increasingly a point of reference for coaching.

While there is an ever-increasing number of specialties of Neuroscience, several are relevant to Coaching:

It is important to note Clinical neuroscience which looks at the disorders of the nervous system, while psychiatry, for example, looks at the disorders of the mind. Coaches should know to identify and refer clients to clinical professionals when disorders of the nervous system or disorders of the mind are suspected.

While the study of the brain is dated back to ancient Greek and Egyptian civilizations, modern neuroscience was advanced when French physician, surgeon, and anatomist Pierre Paul Broca (1824-1880) concluded that different regions in the brain were involved in specific functions. In 1906, Golgi and Cajal jointly received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for their work and categorization of neurons in the brain. Since the 1950s, research and practice in modern neurology have made great strides, leading to developments in the treatment of stroke, cardiovascular disease, multiple sclerosis (MS), and other conditions. But it was only in the 1960s that the term neuroscience was coined.

But it was in 1992 that functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) was first used to map activity in the human brain leading to a great leap forward in the field of neuroscience. Some liken it to the discovery of the microscope in 1725. Others see it as significant as the mapping of the human genome in 2001. The application of new knowledge in neuroscience is now extending well beyond medicine and beginning to influence psychology, education, personal and leadership development, and coaching. The recent explosion in knowledge about the brain – which is estimated to have roughly doubled in just the past twenty years – also offers many practical possibilities, including relieving distress and dysfunction, improving wellbeing, and deepening religious or spiritual practice. Anything that explains or gives insight into the human mind and behavior has great potential for the practice of coaching.

1. The Brain

Even in modern times, scientists call the brain the most complex object in the known universe. We know more about the external world than we do about our internal world of the brain and the mind. Both the brain and the mind are considered to be central not just to our biological functions but to our sense of self, and our aspirations to reach our highest potential to achieve happiness and well-being. It is also associated with the suffering we experience in our lives. Evolved over millions of years, humans have the largest brain in proportion to any living creature on the planet. The main genetic differences between humans and chimpanzees focus on the brain, particularly its social, emotional, linguistic, and conceptual abilities. As an organ in the human body, the average human brain weighs between 1.2 and 1.35Kg, housed in a protective bony skull, similar to tofu inconsistency, and is made up of 1.1 trillion cells including between 90 and 100 billion neurons. It makes up only 2% of body weight but consumes a massive 25% of our energy consumption. Brain scans have shown that we use pretty much all of our brains all of the time, even when we’re asleep — though patterns of activity, and the intensity of that activity, might differ depending on what we’re doing and what state of wakefulness or sleep we’re in.

“Even when you’re engaged in a task and some neurons are engaged in that task, the rest of your brain is occupied doing other things, which is why, for example, the solution to a problem can emerge after you haven’t been thinking about it for a while, or after a night’s sleep, and that’s because your brain’s constantly active,” says neurologist KrishSathian, who works at Emory University in Atlanta, GA.

An average neuron in our brains has about 1000 connections (synapses), 100 trillion in total. Neurons fire 1 – 50 times a second, and sometimes faster; millions of neurons routinely form networks and fire rhythmically with each other dozens of times a second. During a single breath, a quadrillion or more neural signals traveled inside your head. The brain is hyper-connected into a gigantic complex network of circular loops. The number of possible brain states is estimated to be 1 followed by a million zeros[v]. To put this in perspective, the number of particles in the universe is estimated to be “merely” 1 followed by eighty zeros.

Across nearly seven million years, the human brain has tripled in size, with most of this growth occurring in the past two million years[vi]. Ever since our emergence as a distinct species about 200,000[vii] years ago, Homo sapiens, which means wise man in Latin, have had distinct features and functions from other animals. Central to that distinctiveness is the human brain and the mind which is considered by most to be its “physical seat”.

2. The Mind

The most correct thing to say about the mind is that there is a wide-ranging and long-standing dispute between scientists, philosophers, and spiritual traditions regarding its nature. The Mind, in the Western tradition[viii], the complex of faculties involved in perceiving, remembering, considering, evaluating, and deciding. The mind is in some sense reflected in such occurrences as sensations, perceptions, emotions, memory, desires, various types of reasoning, motives, choices, traits of personality, and the unconscious. The Theory of Mind is called a theory insofar as the output (thoughts, feelings, etc.) of the mind is the only thing being directly observed so the existence of a mind is inferred[ix]. Although we have no way of knowing if others also have a mind, it is typically assumed that others have minds analogous to one’s own, and this assumption is based on the reciprocal, social interaction, as observed in joint attention[x], the functional use of language, and the understanding of others’ emotions and actions.

Anil Seth, a professor of cognitive and computational neuroscience from the University of Sussex in the U.K., who specializes in the study of consciousness, has suggested that how we perceive the world is an intriguing process is based on a sort of “controlled hallucination,” which our brains generate to make sense of the world[xi].“In perceiving something, the brain combines these sensory signals with its prior expectations of beliefs about the way the world is to form the best guess of what caused those signals.”This explains the uncanny effect of many optical illusions.

Anil Seth, a professor of cognitive and computational neuroscience from the University of Sussex in the U.K., who specializes in the study of consciousness, has suggested that how we perceive the world is an intriguing process is based on a sort of “controlled hallucination,” which our brains generate to make sense of the world[xi].“In perceiving something, the brain combines these sensory signals with its prior expectations of beliefs about the way the world is to form the best guess of what caused those signals.”This explains the uncanny effect of many optical illusions.

While none knows for certain the full distinction of the nature of the mind and brain, it is increasingly accepted that the brain and the mind are not the same. The brain is a physical organ that is housed within the body. It is the part of the body most associated with the brain. The mind, on the other hand, is not confined to the brain, seems to be “the invisible, transcendent world of thought, feeling, attitude, belief, and imagination.”To summarize:

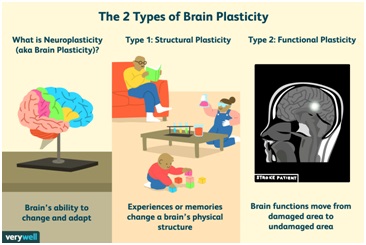

3. Neuroplasticity

One of the great (and most optimistic) qualities of the brain is that it can change. This is called neuroplasticity.

This is the brain’s ability to reorganize itself by forming new neural connections throughout life. Neuroplasticity allows the neurons (nerve cells) in the brain to compensate for injury and disease and to adjust their activities in response to new situations or changes in their environment[xii].

Figure 7: Neuroplasticity explained

Neuroplasticity has significance for any change that we want to experience. By thinking, imagining, doing, or feeling something, we can actually change the form and nature of our grain and therefore influence our habits and our minds.

Link to Coaching: We see clients present with seemingly intractable challenges that they attribute to themselves or others. But the understanding of how the brain and mind works helps to shift perspective. We all see problems as coming from the world outside ourselves. Essentially we interpret sensory inputs from our sense organs and generate perceptions, thoughts, emotions, interpretations, views, and opinions. It’s these that then cause us to perceive and react to what we subjectively think are challenges. The way our mind generates these “mental factors” are related to our childhood experiences when the mass of neurons in our brains became networked in a particular way. Our habitual actions are related to these experiences from childhood and youth and become easily entrenched. Both coach and client are affected by these. The job of the coach is to help create awareness to reveal the underlying issues so that the client can have a shift in perspective that is more useful for him or her. The concept of neuroplasticity supported by our own agency allows new actions to lead to new neural connections, and for establishing new sustainable habits.

4. The Triune Brain

The triune brain is a model of the evolution of the vertebrate forebrain and behavior, proposed by the American physician and neuroscientist Paul D. MacLean. MacLean originally formulated his model in the 1960s and propounded it at length in his 1990 book The Triune Brain in Evolution. It has application not just in clinical sciences but it is increasingly applied in behavioral sciences, education, marketing, as well as in personal development professions such as teaching and coaching.

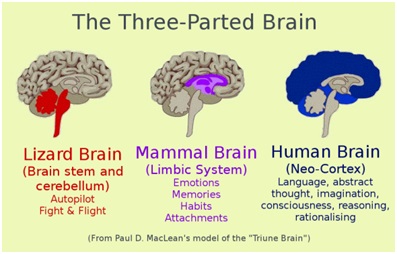

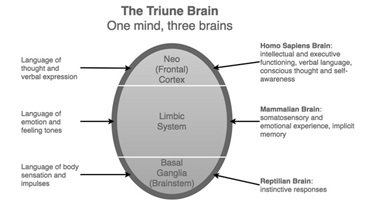

Figure 8: The Triune Brain

Figure 8: The Triune Brain

The model sees three evolutionary stages of the brain, which corresponds to brain structure and function similar to other groups of vertebrates we can track along our evolutionary pathway.

- The Lizard Brain – the oldest part that comprises the Brain Stem and the cerebellum. The lizard brain keeps us alive. It regulates on autopilot our basic bodily functions.

- The Mammal Brain – This part of the brain is made up of The limbic system. It is made up of structures such as the hypothalamus, hippocampus, and amygdala. The limbic system is the major primordial brain network underpinning mood and emotions. It’s a network of regions that work together to process and make sense of the world. Neurotransmitters, such as serotonin and dopamine, are used as chemical messengers to send signals across the network. Brain regions receive these signals, which results in us recognizing objects and situations, assigning them an emotional value to guide behavior, and making split-risk/reward assessments. This part of the brain controls the states we have in common with mammals. As mammals evolved, they gave birth to live young. The development of emotions bonded the young with the mother, and emotions were also needed to collaborate to protect and rear their young.

- The Human Brian – This is the newest part of our brain in terms of evolution. It is our executive center which is responsible for language, logic, and reasoning, abstract thought, imagining, consciousness, and thought. Our self-awareness also lies in this part of the brain and it is made up of the neo-cortex.

Figure 10: The Three Brains, One Mind visualization

MacLean’s model claims that activity in the three brain regions (basal ganglia, limbic system, and neocortex) is largely distinct when we are engaged in each of the mental activities outlined above. For example, when we are in danger and must respond quickly, as an act of self-preservation, the reptilian structure is aroused, preparing us for action by initiating the release of chemicals throughout the body. When we are watching a shocking news story or receive an upsetting message, the limbic system is stimulated and, again, chemicals are released, which create our experience of emotions. Finally, when we are making decisions, solving problems, or reasoning, the neocortex is engaged, without the involvement of the other brain structures[xiii]. Further simplified, the Triune brain – One mind, three brains model – is a useful way to simplify and look at the workings of the brain and mind. In reality, there is no such neat division. Primal, emotional, and rational mental activities are the product of neural activity in more than one of the three regions addressed in MacLean’s model, and their collective energy creates a human experience.

Nevertheless, MacLean’s model provides a clear view of mental activity, which can be beneficial when understanding behavior and supporting people to bring about behavior change.

5. Amygdala Hijack

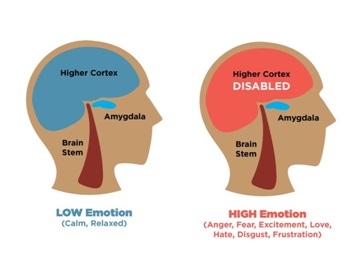

Daniel Goleman, the author of the book Emotional Intelligence and expert on EI, was the first to coin the term Amygdala Hijack. This essentially describes what happens to the brain during these times of crisis.

Figure 11: The Amygdala Hijack, simplified

The amygdalae are two small almond-sized structures in the limbic system that is the mammal brain or the emotional brain described above. During the emotional hijacking, the stressors that we react to (called triggers) can be a real threat or one that is perceived or imagined based on experience. The amygdala disables the higher cortex of the (human) brain to make quick decisions based on the best guess it can make to survive. The hijack prevents us from making sound, rational decisions. The evolutionary point of this was to make sure that we reacted quickly. We evolved to be careful, sense danger, and err on the side of caution to ensure our survival. While this was useful when we were at risk of being eaten by a Saber-tooth tiger, it can be less useful in the urban jungle we live in today. We can also be hijacked by emotional threats. All of these can lead to loss of control, fear, aggression, violence, conflict, breakdown of relationships, and much more.

When we are not triggered, our human brains (neo-cortex) are in control using reasoning and logic to respond to the world. When we are in high emotional states, the amygdala hijack is present and we tend to react without thinking.

There are two critical things you can do to avoid emotional hijack. The first is to increase your emotional intelligence. The second is to identify and proactively address your triggers.

Link to coaching: Understanding the link between the brain, its evolutionary history, and function, help us better understand human behavior. For coaches and clients, it helps us be less judgemental about ourselves and others. The Amygdala hijack explains why people are easily stressed, anxious, angry, and experience internal and interpersonal conflict. It equally helps us find techniques to recognize our triggers and to respond appropriately instead of reacting automatically. We can create kindness and compassion for ourselves and others and truly support the development path.

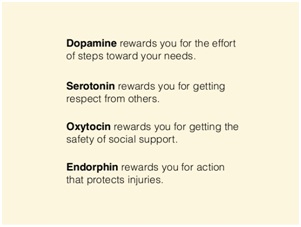

6. Brain Chemicals

Our brains are not just structures. It produces neurotransmitters – brain chemicals used in the transmission of signals between nerve cells – that affect us in profound ways. Our brain has chemicals managed by the parts of the brain that all mammals have in common. When you see something good for you or that you perceive as desirable, the brain releases happy chemicals (dopamine, serotonin, oxytocin, and endorphin). It is meant to entice you to go towards rewards that are good for your survival. Unhappy chemicals (like cortisol) are meant to motivate a mammal to go away from something harmful.

But the mechanism is strongly biased towards survival (not happiness) and most of these chemicals are set during childhood and youth, even though our early experiences may not be those we need to live a happy life as adults. The flow of the chemicals is limited and short. So you have to do more of the same to get the chemicals. This is why old habits are hard to break and new ones take time to establish neural pathways (neuroplasticity).

Figure 12: Summary of “Happy” brain chemicals

Dopamine – is released when a reward is at hand for your effort. Working out at the gym and completing your planned routine will get you a hit of dopamine and keep you going to the gym once the habit is formed. The same goes for working late to finish an important report. It releases extra energy for you to finish the task.

Serotonin – is released when you feel socially superior when you are acknowledged by others. You like this in yourself but hate it in others.

Oxytocin – is released during childbirth and bonding – mother with her new baby and during breastfeeding; but also during sex. It is released when there are touch and trust. Oxytocin drops when you are isolated or separated from your herd or tribe.

Endorphin- is endogenous morphine and masks your pain so that you can do what it takes to survive. It is triggered by vigorous exercise or activity and is meant to be used only in emergencies.

Figure 13: Selected mental states and their corresponding brain chemicals.

We are born with billions of neurons but no connections. Connections build every time the chemicals flow as we experience things. Past rewards and past pains determine how these chemicals flow and the structure of neural networks in the present. Many adults struggle with neural pathways that were built in the past. But, the brain can be re-engineered – neuroplasticity. Experts estimate that a new habit must be repeated 45 times before a new pathway is created. This has significance for coaching as well as other helping professions.

Neuroscience has revealed that certain conditions we experience are the result of the chemicals released in our brains. This has implications for everyone. there are chemicals at play that

While we attribute our emotions to “our self”, the truth is that brain structures and chemicals explain or feelings and the behaviors they elicit. On the other hand, we have the agency to recognize this and intentionally create new patterns of behaviors. We can manipulate these in certain ways. An example would be when you feel threatened or attacked (physically or psychologically) and you have (an automatic) amygdala hijack. This quickly releases fight or flight hormones (noradrenaline and adrenaline) are released getting us in defensive or attack modes. Their effects are first felt in the body – heartbeat increases, increased flow of blood to the large muscle create a sense of heat in the body. We might feel tightness in the pit of our stomachs. When we learn to recognize (including through mindful awareness) the changes quickly, we can recognize the brain and mind reacting in a primal way to ensure our survival. If at this moment, we have the awareness that we are not in any real physical danger, we can use meditation techniques (like mindful breathing) to disarm the amygdala hijack and allow our executive neocortex to take control again, allowing us to respond more appropriately.

Part IV: Aligning Buddhism, Neuroscience, and Coaching

1. The case for meditation

As presented above, the practice of coaching uses several concepts that have their origin in Buddhism and some of these are supported by neuroscience. The most frequently used concepts from Buddhism that have made their way into coaching include:

Mindfulness can be used as a tool for both coaches and clients. The approach was taken by Buddhist meditation (on which non-secular versions like Mindfulness-based stress reduction techniques as popularized by Jon Kabat Zinn) is more akin to coaching that psychological therapy. It is essential for coaches along the coaching process which supports several of the competencies that coaches need to gain and is a skill that can and should, based on scientific evidence, be recommended to clients.

Figure 14: The Buddhist and psychology approach differentiated

2. Types of meditation relevant to the coaching profession

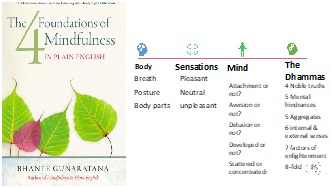

There is a great deal of misunderstanding about meditation in the modern world. Scholar Monk Bhikkhu Bodhi describes that the Satipatthana Sutta[xiv], the Discourse on the Foundations of Mindfulness by the Buddha, is generally regarded as the canonical Buddhist text with the fullest instructions on the system of meditation unique to the Buddha’s own dispensation.

Figure 15: The Four foundations of mindfulness and overview of their sub-types

Figure 15: The Four foundations of mindfulness and overview of their sub-types

Modern-day meditation draws from this broad discourse and instructions by the Buddha 2,600 years ago. The Four Foundations of Mindfulness written by BhanteHeenapola Gunaratne makes this teaching more accessible to us. When we refer to meditation, we are often referring to one of four foundations of mindfulness – mindfulness of the body, and in that only one of three types of meditations. Other names for this include breath meditation, vipassana meditation, Anapanasati meditation, sati meditation. The full framework is given below.

The second type of Buddhist meditation that is used today is Loving Kindness Meditation (LKM). It is also known as loving-kindness meditation (LKM), compassion meditation, or Metta meditation. This type of meditation[xv]is a practice of developing positive feelings, first toward yourself and then toward others, including people you don’t know, your enemies, and all sentient beings. Metta increases positivity, empathy, and compassionate behavior toward others.

LKM is drawn from core Buddhist teachings on kindness, compassion meditation. passion, generosity, patience, sympathetic joy, and the understanding that we are all connected and interdependent and our environments. Loving-kindness meditation results in a positive effect on the mediator’s mood and demeanor.

Figure 16: Key Buddhist concepts of loving-kindness

Figure 16: Key Buddhist concepts of loving-kindness

The third type of meditation in use today is “watching your thoughts or emotions” meditation. This consists of taking note of all sensations, thoughts, and emotions that arise in the mind and letting them arise and pass without judgment and attachment. This is derived from the meditation on sensations and meditation on the mind in the Four Foundations of Mindfulness summarized in Figure 13.

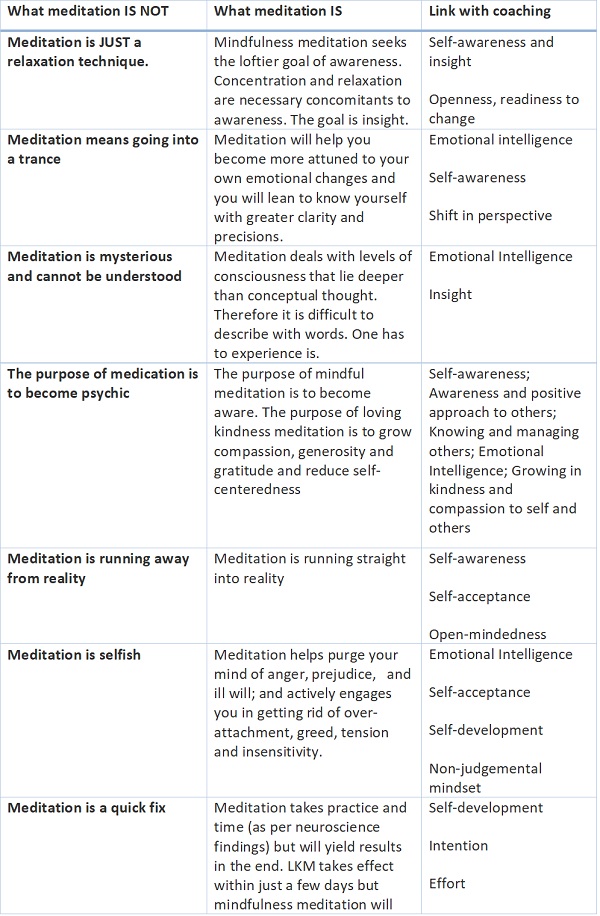

3. Meditation myth busters & coaching

The following corrects common misconceptions about meditation are adapted from Mediazation teacher and Buddhist Monk BhanteHeenapola Gunaratne of the Bhavana Society, In Virginia, USA.

The Buddhist term, “sati” is most commonly translated as mindfulness. Over the years other translators have used other words: awareness, attention, retention, and discernment. Some refer to mindfulness as concentration on an object of meditation. Others rOthers refer to the floating awareness that observes whatever happens in our experience without judging or reacting. Mediation is a broad term that is action or process that aims to lead to mindfulness.

Figure 17: Mind-wandering vs mindful

4. The evidence-based impact of Buddhist practices

The following evidence-based findings are primarily drawn from the book Altered Minds by Daniel Goleman and Richard J Davidson, and other scientific literature that show the benefits of meditation positively impacting brain and mind function[xvi].

Resilience: A mere 30 hours of Mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) practice, which is based on breath meditation, shows dampening (deactivation) of the amygdala – the key node in the brain’s stress circuitry. This reduction is up to 50% when compared with non-meditators. In other words, mediation (breath meditation), increases resilience. Richard J Davidson Ph.D., in his book The Emotional Life Of Your Brain; reports that people who are resilient against the ups and downs of life (the Buddhist concept of equanimity) tend to have up to 30 times the activation of the left prefrontal region of the brain than those who are not resilient. The transmission of signals between tis Left prefrontal region and the amygdalae determine how quickly the executive brain (the human brain) can take over control of the fear/emotional response by the Amygdala in response to triggers.

Emotional stability: Meditation also impacts our mental health by regulating the functioning of the ventromedial cortex, dorsomedial cortex, amygdala, and insula, all of which are specialized brain centers that regulate our emotions, reactions to anxiety, fear, and bodily sensations of pain, hunger, and thirst. Mindfulness meditation can actually change the structure of the brain and affect the mind. In 2011, Sara Lazar and her team at Harvard found that eight weeks of Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) was found to increase cortical thickness in the hippocampus, which governs learning and memory, and in certain areas of the brain that play roles in emotion regulation and self-referential processing. As important, there were also decreases in brain cell volume in the amygdala, which is responsible for fear, anxiety, and stress – and these changes matched the participants’ self-reports of their stress levels, indicating that meditation not only changes the brain, but it changes our subjective perception and feelings as well. A follow-up study by Lazar’s team found that after meditation training, changes in brain areas linked to mood and arousal were also linked to improvements in how participants said they felt — i.e., their psychological well-being.

Compassion: Thinking about or speaking about compassion does not increase compassionate behavior. Humans can display three types of empathy: emotional (I feel what you feel), cognitive (I know what you know), and empathic ( I experience what you experience) empathy. Loving-kindness meditation (LKM) increases empathic concern, activates circuits for good feeling and love, and registers the suffering of others, and prepares a person to act when suffering is encountered. LKM acts quickly showing an effect in as little as 8 hours of practice. 16 hours of practice lead to reductions in usually intractable unconscious bias. The more you practice LKM, the stronger the results. The famous Tibetan monk Mattieu Ricard is a seasoned meditator, with an estimated 62,000 hours of practice. The surge of electrical activity in his brain jumped by 700-800% of the activity of his resting brain when he practiced loving-kindness meditation.

Meditating on a compassionate approach to others shifts resting brain activation to the left hemisphere, a region associated with happiness, and boosts immune functions.

Attention: Breath meditation strengthens selective attention, and longer-term Buddhist Vipassana meditation enhances attention even more. Five months after a meditation retreat, meditators had enhanced vigilance, and the ability to sustain their attention. Just 10 minutes of this type of meditation overcame damage to concentration from multi-tasking. Only 8 minutes of meditation lessened my mind wandering for a while. However, lasting results require sustained practice.

Being present: Meditation promotes mental balance by controlling the “monkey mind” (Luders, Cherbuin, Kurth, 2015). Monkey Mind is a colloquial term for the brain activity known as the “Default Mode Network” (DMN) or being in the state of “Mind wandering”. The DMN is responsible for what we think when we do not attend to anything specific. It causes the mind to wander and engage in non-targeted pieces of information that distracts us. Reduced DMN activity in the brain is the reason why meditators can remain more present-oriented and focused all the time.

Controlling the ego: Both breath meditation and loving-kindness meditation reduce self-centered thoughts and feelings that can allow us to see the world more calmly and objectively, creating a lightness of being where we are not constantly pulling towards or pushing away from things, people, situations, and ideas. This ties back to the Buddhist concept of “no (unchanging) self”, suffering or dissatisfaction and impermanence. Meditation also leaves its mark on the medial prefrontal cortex, commonly known as the “Me Center,” which is the brain site responsible for our perceptions, understanding, and knowledge. When we dedicate ourselves to daily meditation, we can feel more insightful of the self and surroundings, be more empathetic and self-compassionate, and develop more positive connections with each other.

Feeling in control: Neuropsychological studies suggest that regular meditation regulates the functioning of the lateral prefrontal cortex – the area responsible for logical reasoning and rational thinking – making us feel in ‘control’ of our thoughts at all times (Goyal, Singh, Erica, et al., 2014).

Connection to others: Talking about areas of gratitude, in classrooms, at the dinner table, or in the diary, boosts happiness and social well-being, and health. Experiences of reverence in nature or around morally inspiring others improves people’s sense of connection to others and sense of purpose. Research shows just as little as 7 minutes a day of Loving Kindness Meditation affects. Devoting resources to others, rather than indulging a materialist desire, brings about lasting well-being. Watching or hearing about acts of kindness has the same benefits as being kind yourself

A healthier body, healthier mind: Inexperienced meditators, just one day of intensive mindfulness mediation (breathing) down-regulates genes involved in inflammation. The enzyme telomerase, which slows down cellular aging, increases after three months of intensive practice of breath meditation and loving-kindness meditation. A study from UCLA found that long-term meditators had better-preserved brains than non-meditators as they aged. Participants who’d been meditating for an average of 20 years had more grey matter volume throughout the brain — although older meditators still had some volume loss compared to younger meditators, it wasn’t as pronounced as the non-meditators.

Well-being: There is strong scientific proof that meditation improves core physical and psychological assets, including energy, motivation, and strength. Studies on the neurophysiological concomitants of meditation have proved that commitment to daily practice can bring promising changes for the mind and the body (Renjen, Chaudhari, 2017). These include boosting immune functions, greater fertility, better control of our responses during sudden stress encounters and prevents us from a nervous breakdown and panic attacks, stabilizes blood circulation in the body, and regulates blood pressure, heartbeat, metabolism, and other essential biological functioning. It induces a positive shift in lifestyle, meditation improves sleep quality, fosters weight loss, and reduces fatigue.

Mental health: There is strong evidence that mindfulness meditation is as good as medication at treating depression, anxiety, and pain. Loving Kindness meditation has been shown to help people suffering from trauma including those with PTSD. Mindfulness is often coupled with cognitive behavioral therapy as a now common psychological treatment.

Figure 18: Tibetan Buddhist monks taking part in research on mindfulness and its effects on the brain

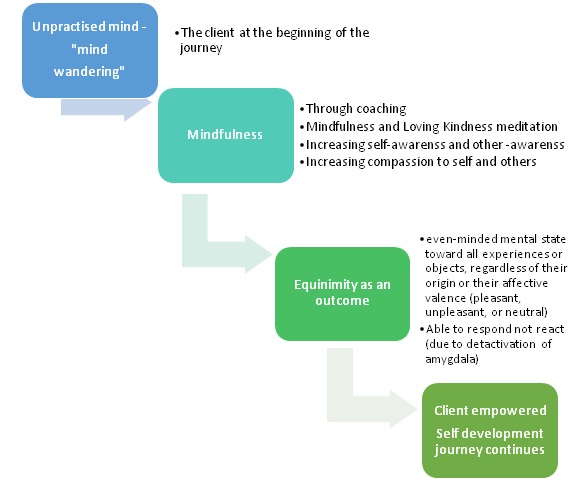

A 2014 article Moving Beyond Mindfulness: Defining Equanimity as an Outcome Measure in Meditation and Contemplative Research by Desbordes et al, states: While “mindfulness” itself has been proposed as a measurable outcome of contemplative practices, this concept encompasses multiple components, some of which, as we review here, maybe better characterized as equanimity[xvii]. Equanimity can be defined as an even-minded mental state or dispositional tendency toward all experiences or objects, regardless of their origin or their affective valence (pleasant, unpleasant, or neutral). In this article, we propose that equanimity be used as an outcome measure in contemplative research. The research team first defines and discusses the inter-relationship between mindfulness and equanimity from the perspectives of both classical Buddhism and modern psychology and presents existing meditation techniques for cultivating equanimity. Then they interface it with psychological, physiological, and neuroimaging methods that have been used to assess equanimity either directly or indirectly. They conclude that equanimity captures potentially the most important psychological element in the improvement of well-being and therefore should be a focus in future research studies. The progression of ideas can be depicted as follows:

5. Conclusion

Coaching is a helping profession that draws and must continue to draw from a wide range of other disciplines. In the current time, unprecedented amounts of research and interest in neuroscience reveal how our behaviors, feelings, and experiences are “wired” in our brains and affect our minds.

Neutral activity in the Amygdalae, which is thought to be evolved from the mammalian brain, is now clearly linked to the processing of emotions. When they are triggered, by real or perceived threats, the amygdale “hijack” the executive center of our brain that is usually responsible for rational thought. This leads to speech and behaviors that are reactive (often with negative consequences). This automatic neural and biochemical reaction when repeated can lead to unhappiness, stress, anxiety, anger, suffering, and can be presented as the starter problem that clients bring to coaching. Coaching is one way of helping clients recognize quickly and disarm the Amygdala Hijack restoring the ability to respond wisely instead of reacting instinctively. Our brains are created for our survival, not our happiness.

However, neuroscience also provides strong evidence that our brains are neuroplastic – they can change structurally and chemically. Thoughts, speech, or actions must be repeated (between 21 and 45 times according to available research) to create new patterns of thought, speech, or behavior.

These two findings which are aligned with coaching practice also provide neuroscience support for Buddhist teachings, here more specifically about the truth of the common human condition of suffering or satisfactoriness; as well as the truth that suffering can be ended by following a certain path (which works on the principle of neuroplasticity).

Two types of ideas come directly from a Buddhist teaching that is used today in coaching and has promise for offering more to the profession and our clients. Buddhist teachings focus on the mind – the person, and not the story of the client – and therefore the link between neuroscience, psychology, and Buddhism offers great insight, resources, and concepts that can be used in coaching. The first is meditation, and there is neuroscientific evidence for how they support self-development and can be applied in the coaching profession.

1. Mindfulness meditation (breath meditation, Anapana sati)

- More feeling of being control: A mere 30 hours of Mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) practice, which is based on breath meditation, shows dampening (deactivation) of the amygdala – the key node in the brain’s stress circuitry. This reduction is up to 50% in already practicing meditators when compared with non-meditators. Meditation regulates the functioning of the lateral prefrontal cortex that contributes to the state of being in control of oneself.

- Resilience (or equanimity in Buddhism) – even-handed reaction to external events – is increased. Meditators using mindfulness techniques tend to have up to 30 times the activation of the left prefrontal region of the brain which controls rational thought processing than those who are not resilient. Resilient brains (and minds) mean can responding mindfully rather than reacting instinctively.

- Mood and emotional stability: Mindfulness meditation increases cortical thickness in the hippocampus, which governs learning and memory, and in certain areas of the brain that play roles in emotion regulation and self-referential processing. As important, there were also decreases in brain cell volume in the stress center, the amygdala. All these results in increased mood and well-being, as well as emotional stability, not only immediately after the meditation but also for weeks afterward.

- Increases attention & focus and decreases mind wandering: Breath meditation strengthens selective attention, and longer-term Buddhist Vipassana meditation enhances attention even more. Five months after a meditation retreat, meditators had enhanced vigilance, and the ability to sustain their attention. Just 10 minutes of this type of meditation overcame damage to concentration from multi-tasking. Only 8 minutes of meditation lessened my mind wandering for a while. However, lasting results require sustained practice.

- Being present: Meditation quietens the “Default Mode Network” (DMN) which is responsible for mind-wandering or the “monkey mind”.

2. Loving-Kindness Meditation

- Empathy, self-compassion, and more positive connections with others: LKM leaves its mark on the medial prefrontal cortex, commonly known as the “Me Center,” which is the brain site responsible for our perceptions, understanding, and knowledge.

The second set of resources to draw on are Buddhist values and core ideas. These include

- The four immeasurable states for which neuroscience provides a scientific basis in brain structure, and brain chemicals. Both these can be changed (neuroplasticity) with persistent repeated Buddhist-inspired practices of four core qualities of the mind from occasional states to boundless and immeasurable states:

- Loving-kindness – caring for the wellbeing of self and others

- Compassion – being moved by others’ suffering and motivated to help

- Sympathetic joy – happiness at the success of others

- Equanimity – the even keel and emotional and cognitive stability regardless of external events, the 8 vicissitudes of life: gain and loss; fame and anonymity; praise and blame; pleasure and pain.

There is evidence that mindfulness meditation and loving-kindness meditation support the development of these states of mind and also change brain structure and chemistry.

These four mental states that correspond to Buddhist Emotional Intelligence are further supported and reinforced by the 10 Buddhist qualities to cultivate throughout life: generosity (even talking about acts of generosity change brain chemicals and activity); virtuous behavior (universal moral standards); wisdom (insight gained from meditation); patience ( the prefrontal cortex is engaged and amygdala and other stress structures are disabled); energy; determination (both related to volitional activity or intention); truthfulness; renunciation (to reduce too much attachment to external objects and situations)) and kindness and equanimity overlapping with the four mind states above. The Noble 8 fold path corresponds to the hard work that is required, in different aspects of one’s life, to achieve one’s fullest potential.