Research Paper By Fatima Edwards

(Life Purpose & Career Coach, UNITED STATES)

Introduction

Self-awareness is defined as

the capacity for introspection and the ability to recognize oneself as an individual separate from the environment and other individuals. [1]

The ability to distinguish our self as separate from our outer world begins early in our childhood development. “As the well-known infant researcher Daniel Stern notes, at about 18 months children begin to show evidence of self-awareness.” [2] However, the self-discovery process does not end in childhood, but continues to evolve throughout adulthood. In fact, “getting to know yourself inside and out is a continuous journey of peeling back the layers of the onion and becoming more and more comfortable with what is in the middle—the true essence of you.” [3]

Over the years, many have explored the relationship between self-awareness and personal effectiveness, and have discovered that self-awareness itself is the foundation for growth, development, leadership and success. The more self-aware a person becomes, the greater the potential for his/her overall effectiveness. Having greater self-awareness can also aid a person in selecting a career or profession that is a good fit for their personality, talents and interests. The more the person knows about their strengths, natural abilities and preferences, the more likely they will make wise career choices.

Within the coaching profession, helping clients to become more self-aware is a critical skill, which can contribute greatly to the success and well-being of the client. While there are various methods for raising self-awareness, the purpose of this case study is to share my personal experiences and insights gained from using assessments as a way to raise the client’s awareness within the confines of a career coaching relationship. While the use of assessments in career coaching is quite useful overall,coaches should be aware of the potential challenges. In this case study I will share both the “good” and the “bad” so that others may benefit.

This document is organized by providing a high-level overview of the assessments, followed by “real life” examples of their application. If desired, the reader may read the entire document or jump to specific sections by clicking on the relevant page numbers in the Table of Contents.

Assessments

This case study examines two assessments that are commonly used to assist individuals professionally, whether it is helping them select the right career or profession, or whether it is helping them to be more effective in positions in which they are already working. These assessments are:

- Myers-Briggs Type Indicator®

- Strong Interest Inventory®

These assessments may be used as stand-alone tools, administered independently of one another, or they may be combined. In fact, there is a Combined Career Report, which provides a list of possible careers based on the combined results of both assessments. The following paragraphs explore each of these assessments in greater detail.

Myers-Briggs Type Indicator®

The Myers-Briggs Type Indicator®, also known as the MBTI®, is a widely used personality assessment that is based on theory developed by Swiss psychiatrist Carl Jung during the 1920s. In 1923 Jung presented his picture of personality in his book entitled, Psychological Types. During the 1920s and 1930s, a mother and daughter team, Isabel B. Myers and Katharine C. Briggs, developed their understanding of psychological type by applying Jung’s ideas to family and friends. Finally, in the early 1940’s, Isabel Briggs Myers began constructing the instrument that would become known as the MBTI® assessment.

Today, the MBTI® tool is used for a variety of purposes including:

“After more than 60 years of research and development, the current MBTI® assessment is the most widely used instrument for understanding normal personality differences. More than two million MBTI® assessments are administered annually in the United States. The MBTI® tool is also used internationally and has been translated into more than 30 languages.”[1]

MBTI® Personality Type Preferences

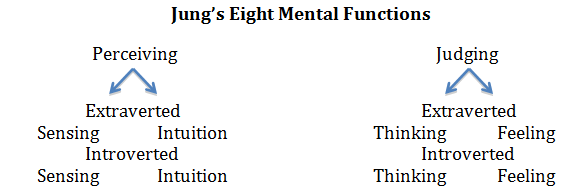

Initially Jung observed that when people’s minds are active, they are involved in one of two mental activities: Perceiving, which involves taking in information, and judging, which involves organizing information and drawing conclusions. He also observed that people are energized either by the external world of people, experience, and activity (Extroversion) or by the internal world of ideas, memories, and emotions (Introversion). From these observations he identified eight mental processes that are generally used by everyone. These mental functions are illustrated in the following diagram:

Jung’s Eight Mental Functions

While these eight mental processes are commonly available for everyone to use, Jung believed that people have a natural preference for one function over another, which leads them to direct energy towards it and to develop behavior and personality patterns that are characteristic of that function. Jung termed one’s preferred mental process as their dominant function.

While these eight mental processes are commonly available for everyone to use, Jung believed that people have a natural preference for one function over another, which leads them to direct energy towards it and to develop behavior and personality patterns that are characteristic of that function. Jung termed one’s preferred mental process as their dominant function.

Jung also observed that people use the eight dominant functions in a hierarchy of preference. The dominant function is the first, and most commonly used. He called the second preference the auxiliary function; the third he called the tertiary function; and the fourth and least preferred he called the inferior function. Briggs and Myers developed Jung’s idea of the auxiliary function, which resulted in the MBTI® 16 personality types shown in the table below:

| Dominant Function | Auxiliary Function | MBTI® Type |

| Introverted Sensing | With Extroverted Thinking | ISTJ |

| Introverted Sensing | With Extroverted Feeling | ISFJ |

| Extroverted Sensing | With Introverted Thinking | ESTP |

| Extroverted Sensing | With Introverted Feeling | ESFP |

| Introverted Intuition | With Extroverted Thinking | INTJ |

| Introverted Intuition | With Extroverted Feeling | INFJ |

| Extroverted Intuition | With Introverted Thinking | ENTP |

| Extroverted Intuition | With Introverted Feeling | ENFP |

| Introverted Thinking | With Extroverted Sensing | ISTP |

| Introverted Thinking | With Extroverted Intuition | INTP |

| Extroverted Thinking | With Introverted Sensing | ESTJ |

| Extroverted Thinking | With Introverted Intuition | ENTJ |

| Introverted Feeling | With Extroverted Sensing | ISFP |

| Introverted Feeling | With Extroverted Intuition | INFP |

| Extroverted Feeling | With Introverted Sensing | ESFJ |

| Extroverted Feeling | With Introverted Intuition | ENFJ |

Each of these 16 MBTI® preferences has specific characteristics that describe a different pattern of behavior and personality. For example, ESFJ types are described as “warmhearted, conscientious, and cooperative;” whereas INTP types are described as “theoretical and abstract, and interested more in ideas than in social interaction.”[2] A great deal of information has been compiled which describes how a person with a particular personality type usually behaves when they are at their best, how others may see them, how they typically behave under great stress and potential areas for growth. Also, the large variety of MBTI® reports provides the individual with a treasure chest of insights, allowing for greater self-awareness and personal growth.

MBTI® Forms

There are multiple MBTI® assessments (also known as ‘Forms’) available. For this reason it is important to select the best assessment based on the objectives of the client. These forms include:

Form M (Step I) Online – Participants answer 93 questions ahead of time and a certified MBTI® practitioner provides the results during an interactive session. While there is no time limit to taking any of the MBTI® assessments, completion of the Form M Online typically takes 20 to 30 minutes. The Form M assessment allows the practitioner to produce various Step I reports.

MBTI® Complete Online – Participants respond to the same 93 questions contained on the Form M assessment, and also participate in an interactive learning session where they can learn about and self-assess their type preferences. They also receive a report on the type preference they chose based on their self-assessment. Completion of the MBTI® Complete Online typically takes 45 minutes to 1 hour.

Form M Self-scorable – This assessment is administered in paper form, typically during an interactive session. After participants complete the questions, they are guided in scoring their responses in order to determine their personality type preference. 30 to 45 minutes should be allotted for assessment completion and self-scoring.

Form Q (Step II) Online – This assessment is the most comprehensive, as it includes the 93 questions contained on the Form M, plus an additional 51 items that allow for more in depth reporting (Step II Reports). Participants complete the 144 questions, and a certified MBTI® practitioner provides the results during an interactive session.

MBTI® Reports

Just as there are multiple assessment forms, there are a variety of reporting options to choose from, depending on the goals of the client. The following is a list of the reports available:

MBTI®Complete (Form M)

Profile + Best Fit Type Description Step I Reports (Form M)

Profile

Profile, College Edition

Personal Impact Report (based on reported type)

Personal Impact Report (based on verified type)

Career Report

Interpretive Report

Interpretive Report, College Edition

Interpretive Report for Organizations

Team Report (Sample of an Individual Client Report)

Team Facilitator Report (This report and Type Table included with Team Report purchase)

Communication Style Report

Report for Healthcare Professionals

Decision-Making Style Report

Stress Management Report

Comparison: Work Styles Report

Conflict Style Report

Step II Reports (Form Q)

Profile

Interpretive Report (based on reported type)

Interpretive Report (based on verified type)[3]

Strong Interest Inventory®

The Strong Interest Inventory® assessment provides a powerful method for matching an individual’s interests with job opportunities, education and leisure activities. “For nearly 80 years, the Strong Interest Inventory® assessment has helped organizations attract and retain the brightest talent and has guided thousands of individuals in their search for a rich and fulfilling life of work and leisure.”[4] Over the years it has become the most respected and widely used career planning instrument in the world

The Strong instrument is based on theory developed by John L. Holland. Holland’s theory suggests that people can be described as falling into one or more of six different occupational types and that the world of work can also be divided into these categories. Using the first letter of the name given to describe each category, these six occupational types are also referred to as RIASEC themes. The following diagram is an illustration of the Holland model containing the six RIASEC themes.

These categories provide a framework for matching people’s interests with the features or characteristics of professional jobs, making them effective in a variety of career coaching scenarios including:

These categories provide a framework for matching people’s interests with the features or characteristics of professional jobs, making them effective in a variety of career coaching scenarios including:

The Strong instrument also refers to the six themes as General Occupational Themes (GOTs). The following describes the characteristics associated with each theme. For example, individuals who score high in the Realistic category will likely prefer work that is physical, produces tangible results, and contains hands-on activities.

Realistic: The Doers – Physical, Tangible Results, Hands-On

Investigative: The Thinkers – Analytical, Theoretical, Inquiring

Artistic: The Creators – Self-Expression, Imaginative, Original

Social: The Helpers – Helpful, Empowering Others, Humanist

Enterprising: The Persuaders – Influencing, Leading, Taking Risk

Conventional: The Organizers – Practical, Orderly, Efficient

Strong Interest Inventory® Results

“Holland’s RIASEC theory provides an organizing simplicity to results on the Strong instrument while at the same time adding a richness and depth to its interpretation.”[5] The easy-to-read report format includes the following:

The following paragraphs describe each of these scales in greater detail:

General Occupational Themes (GOTs) – GOTs reflect the client’s overall orientation to work. They provide broad interest patterns that correspond to the RIASEC theory. These themes generally identify the client’s personality characteristics and their preferred work environments.

Basic Interest Scales (BISs) – BISs report the consistency of interests or disinterests in 30 specific areas such as art or science. They are useful for helping clients identify potential career choices, major fields of study, and leisure activities they may be interested in pursuing.

Occupational Scales (OSs) – OSs represent various occupations that identify the degree of similarity between the client’s interests and the interests of people who are satisfied working in those occupations. These scales help to identify the likelihood that the client will be satisfied working in each occupation.

Personal Style Scales (PSSs) – PSSs measure the client’s personal style preferences identifying how he/she likes to learn, work, assume leadership, take risks and work within teams. By knowing their preferred styles, clients can refine their career choice to fit their preferences.

In addition to these scales, the Strong instrument also provides very useful administrative indexes that help the practitioner identify inconsistent or unusual profiles that may need special attention. A few examples of these special cases are discussed in the “real life” case studies presented in subsequent sections.

Assessments

There are variations of the Strong assessment from which the practitioner may choose, depending on the needs of the client:

Strong Interest Inventory® Assessment – Participants respond to 291 items made up of words or short phrases that enable them to indicate their preferences from among five response options. The answers are then scored to derive individual results. Practitioners may opt to have their clients provide answers on an answer sheet or Internet website.

iStartStrong™ – This assessment is designed to be used by individuals without an interpretation session. The powerful iStartStrong™ Report puts self-discovery into the hands of anyone seeking career direction.

Reports

There are also multiple Strong reports from which to choose, depending on the goals and needs of the client. For example, there are some reports that were designed for high school or college level students, while other reports are more appropriate for working adults seeking a career transition. The following provides a list of the Strong reports available:

Strong Reports

iStartStrong™

Strong Profile, Standard

Strong Profile, College

Strong Profile, College + Strong Interpretive

Strong Profile, High School

Strong Profile, High School + Strong Interpretive

Strong Interpretive Report

Strong and Skills Confidence Inventory Reports

Strong and Skills Confidence Profile

Strong and Skills Confidence + Interpretive

Strong and Skills Confidence + College Profile

Strong and Skills Confidence + College Profile + Interpretive[6]

Additionally, there are a variety of booklets and manuals available for both individuals and practitioners to gain further insights that aid the career exploration process.

Strong & MBTI® Combined Reports

As mentioned previously, there is a Combined Career Report, which provides a list of possible careers based on the combined results of both the MBTI® and Strong assessments. Because both aspects of the client’s personal makeup is considered, the report of potential careers generated from the combined results provides a more powerful and targeted list of occupations that more accurately identifies areas where the client is likely to find job satisfaction.

The following is a list of the Strong and MBTI® Combined Reports that may be run for clients who have taken both the MBTI® and Strong assessments.

Strong and MBTI® Combined Reports

Strong and MBTI® Career Report

Strong Profile plus Strong and MBTI® Career Report

Strong College Profile plus Strong and MBTI® Career Report[7]

Case Studies

Coaching Approach

Prior to administering any of the assessments to clients, I obtained professional certification in all three assessment tools, including the MBTI®, Strong Interest Inventory® and MBTI® & Strong Combined Career Report. These certifications were obtained through the official certification program providers, including CPP, Inc. and GS Consultants.

The steps followed for each client presented in the case studies are as follows:

- Have client complete the Form Q (Step II) Online

- Conduct MBTI® Interpretive session with client:

- Go over each dichotomy in the MBTI® and have client indicate his/her preferences.

- Review MBTI® results with client.

- Verify client’s MBTI® type.

- Have client complete the Strong Interest Inventory® assessment online.

- Conduct Strong interpretive session:

- Go over each General Occupational Theme (GOT) and have client indicate his/her preferences.

- Review Strong assessment results with client.

- Verify client’s highest GOT(s).

- Generate MBTI® & Strong Combined Report using verified MBTI® personality type and verified Strong GOT(s).

- Review Combined Career Report results with client.

- Hold follow-on career coaching sessions with client.

The following sections present three “real life” examples that illustrate the benefits and challenges that may be experienced when using this approach for career exploration.

Case Study #1: The Confirmation

Darlene is a sixty-year old female who was contemplating a career change. Her husband who was a pastor for many years passed away several years ago, which left Darlene struggling to take care of her children by herself for many years. She is currently an instructor at a Christian school that pays very little and she has been struggling financially. As her financial situation continued to cause stress, she wondered whether she should do something different. She came to me for help.

Darlene already possessed a great deal of self-awareness before taking the assessments. During both of her interpretive sessions, she easily identified her preferences, which perfectly matched the assessment results. Her verified MBTI® personality preference is ISFJ, and her verified General Occupational Themes (GOTs) are Investigative, Social and Artistic. Her top themes (Investigative and Social) were tied with a score of 58, and her third highest theme is Artistic with a score of 56. Although the first two themes were tied, Darlene felt that the Social theme described her more accurately than the Investigative theme. Upon further exploration, we verified that her top GOT is Social. Additionally, the Strong revealed that her top 5 Basic Interest Scales (BISs) are as follows:

TOP FIVE INTEREST AREAS

- Religion & Spirituality (S)

- Performing Arts (A)

- Teaching & Education (S)

- Writing & Mass Communication (A)

- Culinary Arts (A)

Since both her Investigative and Social themes were tied, I decided to run two separate combined career reports – one for Social + ISFJ and one for Investigative + ISFJ. Her combined results are illustrated below:

CAREER FIELDS FOR INVESTIGATIVE + ISFJ TYPES

Family Medicine

Speech Pathology and Audiology

Rehabilitation Counseling

Pharmacy

School Psychology

CAREER FIELDS FOR SOCIAL + ISFJ TYPES

Nursing

Religious Education

Child Care

Counseling and Social Welfare

Just as Darlene resonated more with the Social theme during the interpretive session, she also resonated more with the Social + ISFJ career fields. Of all the career fields listed, she most resonated with the Religious Education career field. Additionally, two of her top five interest areas, which are associated with the Social theme as indicated by (S) in the list above, are Religion & Spirituality and Teaching & Education. As Darlene is currently an instructor at a Christian school, both her top interests areas and the top career fields for Social + ISFJ provided confirmation for Darlene, revealing that she was already working in the right occupation.

Further coaching revealed that the real issue was not that a career change was needed, as Darlene thoroughly enjoyed what she was doing. The issue was that she was not making enough money to pay her bills. Darlene’s actions going forward focused on either finding a new job in the same occupation that paid a higher salary, or finding additional work such as outside tutoring or counseling to supplement her income.

Case Study #2: The “Flat” Profile

Lewis is a male college graduate in his late twenties. His father, who is a former co-worker of mine, introduced him to me. Lewis has a strong interest in the Multimedia Production field and has been working on small video shoots sporadically. He also worked as a substitute teacher on occasion. Lewis’ father was concerned that Lewis was having great difficulty finding consistent work and getting a good start in a career/profession after graduating from college. Lewis’ father paid me to help his son find work that would be interesting and fulfilling.

Like Darlene (introduced in Case Study #1), Lewis had a great deal of self-awareness. He knew his personality preferences and basic interests, so verifying his MBTI® personality type and Strong General Occupational Themes was easy. Lewis’ MBTI® personality preference is INTJ, whereas his highest Strong General Occupational Theme (GOT) is Artistic. The MBTI® & Strong Combined Career Report highlights the following career fields for Artistic + INTJ types:

CAREER FIELDS FOR ARTISTIC + INTJ TYPES

Architectural Design

Multimedia Art and Illustration

Technical Writing

Scientific Photography

Lewis strongly resonated with the Multimedia Art and Illustration career field. On the surface this occupation appears to be an easy resolution that could bring closure to Lewis’ career exploration; however, my training as a certified Strong practitioner enabled me to identify an underlying problem. As mentioned previously, the Strong provides administrative indexes that help the practitioner identify inconsistent or unusual profiles that may need special attention. Upon analyzing Lewis’ Strong results more carefully, I realized that his profile was almost completely ‘flat.’ In Strong terms, Flat Profiles are “defined as those with scores in the ‘Little’ to ‘Very Little’ interest range on the General Occupational Themes (GOTs) and Basic Interest Scales (BISs) and that show little differentiation from one Occupational Scale (OS) to the next.”[8] There are various reasons why a client may have a Flat Profile, including:

Each of these reasons should be explored as possible realities during the interpretation session(s).

In most cases, an individual will have multiple (typically 3) General Occupational Themes (GOTs); however, Lewis only had one – the Artistic Theme. Furthermore, the Artistic theme indicated only a “Moderate” level of interest. Of the remaining five GOTs, the Realistic theme indicated “Little” level of interest, and the Social, Investigative, Enterprising and Conventional themes all indicated “Very Little” level of interest.

It was clear that Lewis had very narrow, and well-defined interests. Follow on coaching revealed that not only did he limit his interests to one occupation, but he also limited the environments and conditions under which he was willing to work. He didn’t want to work for a company because he felt that would be too inflexible for him. When we explored entrepreneurship as a possibility, he revealed that he only wanted to accept video assignments that he personally found interesting. If a business owner wanted him to shoot video for a TV commercial, he was not interested. If a couple wanted him to shoot video for a wedding, he was not interested in that either. The only video work that would interest him was in the area of Sports. The narrow limitations that Lewis placed on possible work assignments severely limited his possibilities, which explained why he was not working consistently. The coaching also revealed that low self-esteem and depression could also be issues affecting his job search.

After a few weeks of coaching, Lewis accepted a short-term video assignment located in a different state. We concluded our coaching sessions, with plans to resume the sessions when he returned. After Lewis had departed for work, his father invited me to lunch. During the lunchtime conversation his father happened to mention that depression issues ran in their family. Keeping this in mind if the coaching sessions with Lewis resume, I will further explore the possibility of clinical depression. I will handle this delicate subject very gently, but will recommend actions that are in the best interests of the client. If necessary, I will suggest that Lewis see a therapist since dealing with issues that require therapy falls outside the coaching domain.

Case Study #3: The Multiple Midrange Challenge

Candace is a female in her early fifties who stepped away from her career to have children. Now that her children are almost grown and will be out of the house soon, Candace now wants to start the career she “missed out on” for most of her adult life. Candace was already familiar with the MBTI® and Strong assessments, and knowing that I was certified to administer the assessments, she asked me to generate the reports to help her determine the best career choice.

Unlike Darlene and Lewis, whose interpretations went fairly smoothly as noted in the first two case studies, verification of Candace’s assessment results was not easy at all. The initial MBTI® results indicated that her preferred personality type was INTJ; however, while the ‘T’ and ‘J’ components indicated a clear and strong preference, the ‘I’ and ‘N’ components contained facets that were mostly in the midzone. Midzone results occur when the client ‘splits the vote’ which produces a result in the middle.[9] In Candace’s case, it was not very clear whether she preferred Introversion (I) or whether she preferred Extroversion (E). Additionally, it was not clear whether she preferred Sensing (S) or whether she preferred Intuition (N). Candace’s MBTI® type could be INTJ, ENTJ, ISTJ or ESTJ.

During the interpretive session, clients are asked to select their preferences in order to verify their type. If that approach does not work, they are asked to read the relevant MBTI® type descriptions to determine which type fits them the best. Candace was unable to identify clear preferences in the first exercise, so she read the descriptions for INTJ, ENTJ, ISTJ and ESTJ. Again, she could not distinguish which one fit her better. She believed that she could be any one of them. Neither of the two approaches surfaced clear preferences so the MBTI® verification was not successful.

Candace’s Strong results were not clear either. According to the Strong interpretation guidelines, whenever two General Occupational Theme (GOT) scores are within five points of each other, and their interest levels are the same (e.g. High, Moderate, etc.), they are considered a tie. Candace’s GOT results were as follows:

Enterprising (E) Very High 72

Conventional (C) Very High 68

Social (S) Moderate 54

Artistic (A) Moderate 53

Investigative (I) Moderate 47

Realistic (R) Moderate 44

Technically, the results show a tie between Enterprising and Conventional, a tie between Social and Artistic, and a tie between Investigative and Realistic.

Based on the highest scores, the report indicated that Candace’s highest themes were ECS; however based on the tie, they could just as easily be ECA. I ran several MBTI® & Strong Combined Career Reports, which yielded the following results:

CAREER FIELDS FOR ENTERPRISING + INTJ TYPES

Corporate Executive Management

Marketing Research

Management Consulting

Law and Politics

CAREER FIELDS FOR ENTERPRISING + ENTJ TYPES

Sales Management

Corporate Executive Management

Management Consulting

Law and Politics

CAREER FIELDS FOR ENTERPRISING + ESTJ TYPES

Retailing

Small Business Management

Corporate Management

Sales Management

Career fields involving Management were common in all three reports, whether it is Corporate Management, Small Business Management, Sales Management or Management Consulting; however landing these positions would be difficult for Candace, given the amount of time she has not been working. The assessment results that we generated did not clearly identify work that would be feasible for Candace at this particular point in her life.

Since the Enterprising and Conventional themes also tied, it would have been just as appropriate to run combined reports for Conventional + INTJ, Conventional + ENTJ or Conventional + ESTJ but the client did not opt to run these reports.

After considerable soul searching on her own, Candace settled on Forensic Accounting, which is aligned with the Conventional theme. She has passed her Certified Public Accounting (CPA) exam and is currently pursuing the credentials needed to work in Forensic Accounting.

Summary

In the majority of cases, the MBTI® and Strong assessments are very effective in raising awareness and assisting in the career exploration process. Both the coach and the client may benefit from the awareness that is surfaced when analyzing the assessment results. In all three of the previous case studies, the clients felt that there was great value in taking the assessments. Both Darlene and Lewis were able to validate what they already knew about their personality and preferences, and both received confirmation that they had selected suitable career fields. In addition to the lists of possible careers, the assessments also provided insights, such as communication styles, risk-taking preferences and conflict resolution tendencies, which were beneficial for each client, even for Candace whose career results were more difficult to interpret. As a coach, I also gained greater insights about each client, which helped me to coach each one more effectively, based upon their individual preferences and styles. I learned that Lewis was very artistic, so I was able to effectively use visualization and other creative techniques, which he found to be very motivating. I learned that Darlene had a heart to help people and cared very deeply for others. At times our coaching sessions shifted toward what she could do to improve troubled relationships, once focusing on a communication issue that surfaced with one of her students, and another time discussing an argument she had with her daughter-in-law.

While in most instances the use of these assessments has proven to be very useful, it is important to acknowledge that the results produced by these instruments may not be easy to interpret, and may even cause confusion for the client. As examples, challenging interpretation issues, such as “Flat Profiles” and “Midzone Results,” must be addressed by those who have the knowledge to analyze the results correctly. As a result, these assessments should only be administered and interpreted by certified practitioners who have been properly trained. Utilizing certified practitioners to analyze assessment results has become especially important, as the ability to complete assessments via the Internet has greatly expanded over the years. There are several “knock off” assessments that disguise themselves as the real thing, when in fact they are unproven replicas, which will likely provide inaccurate results. Fortunately, there are official training organizations that equip individuals with the knowledge and tools to ensure that the MBTI® and Strong assessments are used appropriately. Administration and/or interpretation by someone who is not certified will likely yield inaccurate results. When administered appropriately, the MBTI® and Strong assessments can produce a wealth of information that is highly beneficial for the Career Coach, who seeks to understand their clients better, as well as the client who will likely gain valuable insights that can help them to be more effective in their careers.

Bibliography

Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. Wikipedia.

<https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Self-awareness>. Accessed 14 September 2015

Holiger, Paul C. “Great Kids, Great Parents.” Psychology Today, 19 November 2012, <https://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/great-kids-great-parents/201211/self-awareness>. Accessed 14 September 2015.

Bradberry, Travis and Jean Greaves. Emotional Intelligence 2.0. San Diego: TalentSmart®, 2009.

Myers, Isabel Briggs. Introduction to Type®, Sixth Edition, ed. Kirby, Linda K. and Katharine D. Myers. Mountain View: CPP, Inc., 1998.

CPP, Inc. CPP Sample Reports. <https://www.cpp.com/samplereports/reports.aspx>. Accessed 14 September 2015.

CPP, Inc. SkillsOne® – CPP’s Online Assessment System webpage. <https://www.skillsone.com/contents/strong/strong.aspx>. Accessed 15 September 2015.

Gutter, Judith and Allen L. Hammer. Strong Interest Inventory® User’s Guide – Practitioner’s Tool for Understanding, Interpretation, and Use of the Strong Profile and Interpretive Report. Mountain View: CPP, Inc., 2012.

Donnay, David A. C., Michael L. Morris, Nancy A. Schaubhut, Richard C. Thompson, Lenore W. Harmon, Jo-Ida C. Hansen, Fred H. Borgen, and Allen L. Hammer. Strong Interest Inventory Manual, Revised Edition – Research Development, and Strategies for Interpretation. Mountain View: CPP, Inc., 2005.

CPP Professional Services. MBTI® Certification Program Participant’s Resource Guide. Mountain View: CPP, Inc., 2011.

[1] Isabel Briggs Myers, Introduction to Type®, Sixth Edition, ed. Linda K. Kirby and Katharine D. Myers (Mountain View: CPP, Inc., 1998), 5.

[2] Isabel Briggs Myers, Introduction to Type®, Sixth Edition, ed. Linda K. Kirby and Katharine D. Myers (Mountain View: CPP, Inc., 1998), 13.

[3] CPP, Inc., CPP Sample Reports, <https://www.cpp.com/samplereports/reports.aspx> (14 September 2015).

[4] CPP, Inc., SkillsOne® – CPP’s Online Assessment System webpage, <https://www.skillsone.com/contents/strong/strong.aspx> (14 September 2015).

[5] Judith Gutter and Allen L. Hammer, Strong Interest Inventory® User’s Guide – Practitioner’s Tool for Understanding, Interpretation, and Use of the Strong Profile and Interpretive Report (Mountain View: CPP, Inc., 2012), 1.

[6] CPP, Inc., CPP Sample Reports, <https://www.cpp.com/samplereports/reports.aspx> (14 September 2015).

[7] CPP, Inc., CPP Sample Reports, <https://www.cpp.com/samplereports/reports.aspx> (14 September 2015).

[8] David A. C. Donnay et al., Strong Interest Inventory Manual, Revised Edition – Research Development, and Strategies for Interpretation (Mountain View: CPP, Inc., 2005), 173.

[9] CPP Professional Services, MBTI® Certification Program Participant’s Resource Guide (Mountain View: CPP, Inc., 2011), 111.