Research Paper By Elizabeth Tuleja

(Global Leadership Coach & Cross-Cultural Management Coach, CHINA)

Abstract: CQ – or Cultural Intelligence – is an important theoretical model used in the field of intercultural communication and cross-cultural management. It is related to but not identical to the well-known literature behind Social Intelligence (SI) and Emotional Intelligence (EQ). This research project explains the early foundations of SI and EQ and then introduces the concept of CQ along with the process of Mindfulness which can be used in the coaching profession.

Background

The Beginnings of Multiple Intelligences

Intelligence quotient, IQ, comes from the word, Intelligenz quotient, which was established in the early 20th-century work done by German psychologist, William Stern.[1] The IQ test today is a measure of reasoning ability that gauges how a person uses information and logic to answer a series of questions. The IQ score involves answering puzzle-type questions requiring information recall and speed.[2] For many decades, IQ was the primary means by which a person’s intelligence was measured.

However, Harvard psychology professor, Howard Gardner, turned the table on this singular approach to assessing a person’s intelligence. In his 1983 trailblazing book, Frames of Mind: The Theory of Multiple Intelligences,[3] he argued that there are many forms of human intelligence because of the complex nature of the individual, such as learning styles, personality, and behaviour. He introduced the idea of “multiple intelligences” that include both intrapersonal (understanding your own feelings and motivations) and interpersonal (understanding intentions and motivations of others) skills and posited that IQ (Intellectual Quotient) is not sufficient to explain a person’s entire cognitive ability; something more was needed. His theory quickly became a classical model by which to recognize the complexity of human intelligence. While IQ was initially thought to be stable over a person’s life (e.g., if you were tested as a child and receive a certain score, then that is your score for life), Gardner’s theory of multidimensional aspects of intelligence grew over the next decade[4] and showed that many aspects of intelligence exist (abstract, social, emotional, practical, aesthetic, and kinesthetic)and are capable of improving over a lifetime depending on experiences and growth opportunities. Two important theories are social intelligence and emotional intelligence.

Social Intelligence

Social intelligence is the ability to understand and manage situations when interacting with people – to be able to work and play well with others. It’s the awareness of situations and social dynamics and then the ability to use strategies for cooperation and understanding for positive outcomes. There are five aspects of Social Intelligence:

Application for Coaching

In coaching situations, you may find yourself with a client who struggles with the ability to interact with others in a meaningful way. Understanding the basics of Social Intelligence will provide a strong foundation for helping walk your client through a greater understanding of what it takes to interact with people. Questions to ask them could be:

Presence: Think about yourself at work and how you present yourself to different people (peers, superiors, direct reports). For each of these three groups, what is the image (your presence) that you strive to present – describe it. How is that working/not working for you? What would a trusted friend say about your presence?

Clarity: When communicating, how do you express yourself (e.g., do people understand you and then follow instructions with productive results?). Possibly spend some time monitoring yourself and see what is revealed.

Awareness – How attuned to social contexts and cues are you? When was the last time you had to quickly assess a social situation and act? What happened?

Authenticity – How do you demonstrate to others that you are approachable and someone who can be trusted (e.g., you “walk the talk”). If your close friend (or colleague) were to give you feedback, what might they say?

Empathy – How are you at connecting with people and showing that you hear them and are concerned for their well-being?

Emotional Intelligence

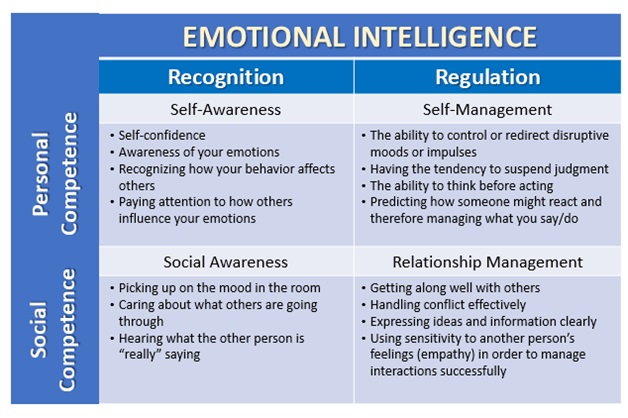

Emotional intelligence goes a step further beyond Social Intelligence because it is about personal competence as much as social competence. EQ is about self-awareness and self-regulation. See Figure 1.

Daniel Goleman, also a Harvard professor and psychologist, popularized the concept of emotional intelligence, which is the ability to recognize, understand, and manage emotions both in ourselves and in others. After the immediate success of his book, Emotional Intelligence (1995), the public resonated with what he had to say about “Emotional Intelligence and the Workplace.”[6] His idea of emotional intelligence laid the foundation for the intangible yet indispensable aspects of being a competent member of society, whether it is in the workplace or elsewhere. This competence, he argues, is founded in our ability to connect on an emotional and subliminal level with those around us.

His research showed that in the workplace, EQ contributes 80 to 90% of the competencies that distinguish outstanding leaders from average leaders.[7] A person with a high EQ possesses the following attributes.

Here is an example: If you’re managing a team of several individuals all with different backgrounds and personalities, you need to be aware of what makes them“tick” both on an individual level and as a group. An effective leader will listen in order to earn the individual’s confidence and respond with equanimity during a crisis. To understand others, the EQ leader must be aware of her own feelings, what motivates her, and what makes her “tick.” If you’re a team leader, you would be wise to listen to your team and find out what is important to them. If the others are facing challenging circumstances, you address them while keeping your own emotions in check. You would remain calm and cool under pressure, recognizing how others around you could trigger your pressure points. You would look several steps ahead in order to foresee potential conflicts and spend the necessary time managing relationships with your team.

Figure 1: Emotional Intelligence is about Personal Awareness as well as Social Awareness (Credit: E.A.Tuleja)

Application for Coaching

In coaching situations, you may find yourself with a client who needs to develop better self-awareness. While Social Intelligence is outward-looking, Emotional Intelligence is inward-looking. Some questions to ask:

Self-Other-Awareness: When _____ happens, what are you feeling? Thinking? What types of non-verbal responses (sounds, looks, gestures) might you display? Think of a recent event and how you responded. When you think about how you reacted, responded, approached the person, what do you think s/he might have been feeling?

Self-Regulation: How can you become more aware of your emotions and attitudes? What are some things you could do to control your emotions and actions under pressure? Who is someone you admire and what do they do when under pressure or during times of stress?

Motivation: How might you motivate yourself to think first of the possible needs of others? What might be stopping you from learning about the needs of others? What is one thing you could do today to become more aware of other people’s emotions?

Empathy: How might you put yourself in the other person’s shoes and treat them accordingly. When was a time when you were given slack or the benefit of the doubt? What happened? How did you feel?

Social Skills: For this attribute, an exercise might be helpful – you could ask your client about someone they admire (e.g., someone who feels comfortable in a crowd and “works the room”). Think about what makes them at ease in meeting people and building relationships.

Cultural Intelligence

Cultural Intelligence (also known as Cultural Competence) has its roots in social and emotional intelligence (as previously mentioned)but takes this self-and other-awareness even further. CQ is a person’s ability to function skillfully in a cultural context different than one’s own.[8][9][10] This means that a culturally intelligent person is someone who is not only able to empathize and work well with others, but can acknowledge differing values, beliefs, attitudes, and behaviours in order to anticipate, act, and react in appropriate ways to produce the most effective results, and then to reevaluate and try acting or reacting in a different way.[11] Earley and Mosakowski propose that:

[While] a person with high emotional intelligence grasps what makes us human and at the same time what makes each of us different from one another...a a person with high cultural intelligence can somehow tease out of a person’s or group’s behaviour those features that would be true of all people and all groups, those peculiar to this person or this group, and those that are neither universal nor idiosyncratic. The vast realm that lies between those two poles is culture.[12]

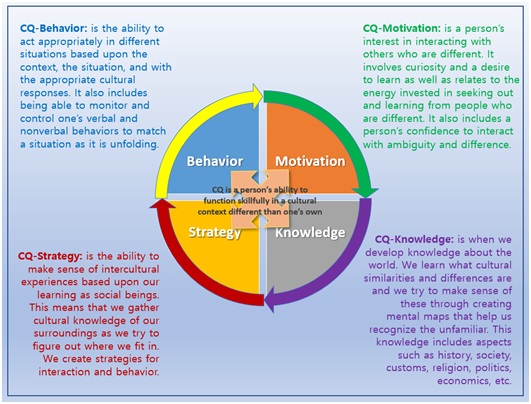

Earley and Ang’s pioneering theory of CQ comprises three critical elements necessary for effective intercultural interaction: cognitive, motivational, and behavioural.[13] The cognitive aspect is needed to conceptualize and process new information. This is more than simply having knowledge about a culture, but the ability to transfer learning to different cultural contexts. The motivational aspect is needed for adapting to different cultural norms and values. However, it is more than just adapting to a nun familiar environment; rather, it means that a person possesses the interest and curiosity—the drive—to respond to ambiguity. The behavioural aspect is needed in order to engage effectively and appropriately in intercultural interactions. [14]

The work of Van Dyne and colleagues[15] extends the original CQ theory and focuses on the process of cultural intelligence, which takes into consideration the experiential aspect of what one learns and re-learns after reflecting on the experience. Van Dyne has identified four factors of CQ which include CQ strategy, knowledge, motivation, and behaviour.

Figure 2: Four Factors of Cultural Intelligence(Credit: E.A.Tuleja)

Application for Coaching

In coaching situations when you have an ex-pat living in a different country than her/his own; a manager who is dealing with a multicultural workforce at home; or a leader from a company that will be – or is – doing business across borders, these questions can prove helpful in helping your client become more culturally intelligent. Some questions to ask:

CQ Strategy: What are the things you can do (in your control) in order to anticipate how you will interact and behave in _____? How might you find assistance before you leave? Once you are there? When do you return? What will that look like?

CQ Knowledge: What do you know about the values, beliefs, attitudes, behaviours, and norms of country ____/place _____? How might this knowledge help you in your daily activities (job and personal)?

CQ Motivation: What can you do to become more curious about WHY people do/say the things they do (and not just WHAT)? How can you find out more information? What are some ways to step out of your comfort zone and explore ways of thinking, doing, interacting with the unfamiliar? What can you do to help develop emotional hardiness during times of stress?

CQ Behavior: What behaviours (different than in your country) are you aware of in [country ____] and what do they mean? How do you react when behaviours don’t make sense, are contrary to what you are used to, and seem unusual or strange?

Differences between SI, EQ, and CQ

While many theorists suggest that social intelligence (SI), emotional intelligence (EQ) and cultural intelligence (CQ) are linked, there only have been a few studies that examined them together in order to explicate their nuances. One recent study examined whether SI was superordinate to EQ and CQ. The findings – cultural intelligence is distinct but related to emotional intelligence, and not a subset of SI.[17]

Some examples can assist in highlighting the differences:

In order to be effective in a social situation, one needs EQ (ability to manage self and others) yet someone with high SI may not have high EQ – for example, maybe that person can communicate well in a social setting but is not capable of handling someone crying. However, someone who can manage an emotional situation (crying) is usually able to handle a social situation – so, individuals with high EQ will likely have high SI bc their emotional interactions with others will be more effective and aid in social interactions. [18]

Social intelligence skills may not carry over to other cultures.[19]For example, you may be socially and emotionally intelligent in your environment but not in another. However, people high in CQ are usually high in SI because someone able to interact successfully with other cultures will likely be able to successfully interact within their own culture. [20]

CQ does not always require a high level of EQ. For example, understanding appropriate cultural behaviours, such as shaking hands, doesn’t require EQ. Some aspects of EQ are not related to CQ because many aspects of EQ involve internal processes. For example, perceiving and understanding one’s own emotions is not influenced by being culturally intelligent. So, one could have high EQ but not CQ. So, CQ has some components that are distinct from EQ.[21]

In sum, CQ is expanding on SI and EQ because it addresses an extra layer of complexity in determining what things mean with differences – as a result, this requires a person to gain deep self-awareness and strive for other-awareness in situations that are not familiar.

Now that we have discussed the various components of Cultural Intelligence, it’s important to demonstrate how one can develop this important set of CQ skills.

The PROCESS of Mindfulness and CQ

Mindfulness

Mindfulness is a metacognitive strategy that the culturally intelligent person must practice if she or he is to be successful in cross-cultural interactions. Mindfulness requires reflectively paying attention through monitoring personal feelings, thoughts, and actions. It allows people to make sense of cultural situations, events and actions within one’s frame of reference by removing a rigid or fixed mindset, also known as “cultural sense-making,” which is the terminology used in certain global leadership literature. [22] They define cultural sense-making (which will be discussed later in this article) as a cognitive approach that helps us to organize and interpret information—away from that we can make sense of our perceived social reality—it is a form of mindfulness.

Mindfulness originally stemmed from Eastern spiritual traditions of meditation, which prompts a person to consciously observe and change one’s mental habits. This form of mindfulness considers mental, emotional, and physical states, which helps an individual being touch with internal thoughts and feelings in relation to external conditions. The goal is to focus on the present moment and be aware of those intuitive notions or ideas that come to mind and open up new insights. [23]For example, if you are having negative thoughts and you want to rid yourself of the manifestations of those negative thoughts, you identify what might be causing the negativity and then focus on having positive thoughts about that subject. Even breathing can be developed as a tool to help control negative distractions and build positive concentration. [24]This enables you to become aware of such negativity in order to mindfully transform your thinking. In brief, you monitor what you are thinking and how this is affecting emotional, attitudinal, or physical well-being in order to respond and act in an appropriate manner.

The construct of mindfulness has attracted significant attention in a variety of academic and professional fields. Mindfulness was introduced to the field of psychology by Langer[25] then carried over to the field of interpersonal communication[26] and eventually found its way into the intercultural literature[27] as well as in the area of global leadership.[28] In the field of education, the construct of mindfulness is often referred to as the reflective practice[29][30] and in business education (the reflective leader–manager).[31][32][33][34][35][36]

Mindlessness

To this end, the opposite of being mindful is mindlessness, like being on auto-pilot. With mindlessness, there is no need to think about what you are doing because it comes naturally and is accepted and expected—you certainly don’t need to question your assumptions because you expect everything to happen the way it always has. This is ethnocentrism, which blinds us to the multiple reasons and possibilities behind any situation or interaction.[37] When someone only perceives the world from one framework, that person is exhibiting mindlessness.

When working with clients while developing global leadership skills it is imperative to remember that business acumen does not necessarily equate cultural competency. For example, knowing how to navigate through the process of creating a joint venture is not the same as being able to successfully interact with counterparts on an interpersonal or intercultural level. Past and current research into cross-cultural communication in management suggests that we first must know our- selves before we can know others, and then attempt to create bridges between what is known and what is not known—cultural intelligence. [38] This concept of mindfulness, or reflection, is critical to the development of a leader who wants to be culturally intelligent and successful in any multicultural setting.

Some Examples of Mindfulness that Demonstrate CQ

Metaphors can be a powerful device when encouraging clients to envision themselves in a situation. The theatrical metaphor of “front-stage–back-stage” culture[39] is helpful in explaining mindfulness. When we view a theatrical production, we are merely passive spectators observing the illusion of real events as portrayed by the actors on stage. While this can be enjoyable and entertaining, we miss out on all the action going on behind the curtain. Perhaps we have read up on the playwright beforehand or know something of the play’s theme and meaning. This understanding will surely help with the overall enjoyment of what is happening. But this is not the full view. If we have any curiosity about theatrical workings, we might choose to go backstage after the curtain call and steal a glimpse of all the props and mechanical devices that go unnoticed throughout the production (CQ Motivation). Or, we might have the opportunity to become stagehands ourselves and learn all of the inner workings of how the production is fabricated—in essence, we are able to understand not only what is happening, but why it is happening because of our insider’s view of what is going on behind the scene (CQ Knowledge). By going backstage, we have become active participants rather than passive spectators.

Another example could be attending a Chinese banquet where you know that there are certain foods that you do not care to eat. In contemplating the situation, you think about how you have handled situations like this before (CQ Strategy) —you don’t want to insult your host, but you also don’t want to eat something that is distasteful to you. You imagine the scene in your mind—your host offers you a delicious morsel—you refuse; the host offers it again—you refuse When you observe the cues of your host—he will probably smile and continue to offer you the food—at the same time, you will be trying to maintain a pleasant look on your face as well a stone while you continue to decline the food. You know that this culinary delight upsets your stomach, so you naturally think about how with as affected you in the past. But you also know how important formality and graciousness is within the Chinese culture—you certainly do not want to offend your host. Finally, you monitor your actions which might be a to tell the host how delicious such a delicacy is and how you are honoured by your host’s selection of such a treat; but you also politely state that you are watching your cholesterol, so for health reasons, you must, unfortunately, decline (CQ Behavior).

Conclusion

These situations serve as examples of how one can develop her or his CQ through the process of mindfulness. By being aware that cultural differences exist, a person can master the four aspects of Cultural Intelligence.

First, they can use the CQ Strategy to predict, decipher, and adjust perspectives and behaviour to a given situation. Second, they can use CQ Knowledge, which is what they know about the aspects of the culture or language, or region in order to interpret the different values, norms, and behaviours. Third, they can tap into CQ Motivation, which is a person’s interest in people and the culture itself. The CQ motivated person enjoys learning and applying what she has learned with interest and confidence—she is comfortable with herself and with the ambiguity that comes when crossing cultures. And fourth, they can apply their CQ Behavior by style-shifting their actions, attitudes, and perceptions based upon what they know – and what they don’t know, they will see out by asking someone.

This research has paper provided the historical background of Social, Emotional, and Cultural Intelligence in order to focus on CQ and the process of Mindfulness. By understanding the four aspects of Cultural Intelligence (Strategy, Knowledge, Motivation, and Behavior) as well as the process of Mindfulness, it is possible to help our clients(and ourselves) understand who they are– and who others are – in this diverse, complex, and challenging world.

Sources

[1]Stern, W. (1912).Die psychologischen Methoden der Intelligenzprüfung und Deren Anwendung a Schulkindern(Vol. 5). JA Barth. [English translation: The Psychological Methods of Testing Intelligence]. Educational psychology monographs, no. 13. By Guy Montrose Whipple Baltimore: Warwick & York.]

[2]What is IQ — and how much does it matter? Allison Pearce Stevens, October 13, 2016. Retrieved June 1, 2019, from:https://www.sciencenewsforstudents.org/article/what-iq-and-how-much-does-it-matter

[3]Gardner, H. (1983). Frames of mind: The theory of multiple intelligences. New York, NY: Basic Books.

[4] Gardner, H. (1993).Multiple intelligences: The theory in practice.New York: Basic Books.

[5]What is social intelligence? By Hsin-Yi Cohen. August 1, 2014. Retrieved June 1, 2019, from http://www.aboutintelligence.co.uk/social-intelligence.html

[6]Goleman, D. (1995). Emotional intelligence. New York, NY: Bantam Books.

[7]Goleman, D. (1998). Working with emotional intelligence. New York, NY: Bantam Books.

[8]Earley, C. P. & Ang, S. (2003). Cultural Intelligence: Individual interactions across cultures. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

[9] Ng, Kok-Yee, Linn Van Dyne, and Soon Ang, (2009a), “From experience to experiential learning: Cultural intelligence as a learning capability for global leader development”, Academy of Management Learning and Education 8, 511–526.

[10] Ng, Kok-Yee, Linn Van Dyne, and Soon Ang, (2009b), “Developing global leaders: The role of international experience and cultural intelligence”, Develop Advances in Global Leadership 5, 225–250.

[11] Rockstuhl, Thomas, Stefan Seiler, Soon Ang, Linn Van Dyne, and Hubert Annen, (2011), “Beyond general intelligence (IQ) and emotional intelligence (EQ): The role of cultural intelligence (CQ) on cross-border leadership effectiveness in a globalized world”, Journal of Social Issues 67, 825–840.

[12] Earley, P. Christopher, and Elaine Mosakowski, (2004), “Cultural Intelligence”, Harvard Business Review, 139–146.

[13]Earley, C. P. & Ang, S. (2003). Cultural Intelligence: Individual interactions across cultures. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

[14] Earley, P. Christopher, and Randall S. Peterson, (2004), “The elusive cultural chameleon: Cultural intelligence as a new approach to intercultural training for the global manager”, Academy of Management Learning & Education 3 (1), 100–115.

[15] Ang, Soon, Linn Van Dyne, Christine Koh, K. Yee Ng, Klaus J. Templer, Cheryl Tay, & N. Anand Chandrasekar, (2007), “Cultural intelligence: Its measurement and effects on cultural judgment and decision making, cultural adaptation, and task performance”, Management and Organization Review 3 (8), 335–371.

[16] Van Dyne, Linn. (2012). The four factors affecting cultural intelligence (CQ). Retrieved from

[17]Crowne, K. A. (2013). An empirical analysis of three bits of intelligence. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science, 45(2), 105-114.

[18] Ibid., p. 108.

[19]Brislin, R., Worthley, R. & Macnab, B. (2006). Cultural intelligence: Understanding behaviours that serve people’s goals. Group & Organization Management, 31, 40-55.

[20]Crowne, K. A. (2013). An empirical analysis of three bits of intelligence. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science, 45(2), p. 109.

[21]Moon, T. (2010). Emotional intelligence correlates of the four-factor model of cultural intelligence. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 25(8), 876-898.

[22] Bird, Alan, and Joyce S. Osland, (2006), “Making sense of intercultural collaboration”, International Studies of Management and Organization 35 (4), 115–132.

[23] Baer, Ruth A., Gregory T. Smith, Jaclyn Hopkins, Jennifer Krietemeyer, and Leslie Toney, (2006), “Using self-report assessment methods to explore facets of mindfulness”, Assessment 13 (1), 27–45.

[24] Hanh, Thich Nhat, (1975), “The Miracle of Mindfulness”, (Beacon Press; Boston, MA).

[25] Langer, Ellen, (1989), “Mindfulness”, (Addison-Wesley; Reading, MA). Looman, Mary D., (2003), “Reflective leadership: Strategic planning from the heart and soul”, Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research 55 (4), 215–221.

[26]Burgoon, Judee K., and Ellen J. Langer, (1995), “Language, fallacies, and mindlessness- mindfulness”, Communication Yearbook 18, 105–132.

[27] Ting-Toomey, Stella, (1999), “Communicating Across Culture”, (Guilford; New York: NY).

[28] Mendenhall, Mark E., Joyce S. Osland, Alan Bird, Gary R. Oddou, and Martha L. Maznevski, (2008), “Global Leadership Research, Practice and Development”, (Routledge; New York, NY). Mezirow, John, (1981), “A critical theory of adult learning and education”, Adult Education 32 (1), 3–24

[29] Kember, David, Jan McKay, Kit Sinclair, and Francis K. Y. Wong, (2008), “A four-category scheme for coding and assessing the level of reflection in written work”, Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 33 (4), 369–379.

[30] Schön, Donald A., (1983), “The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action”, (Basic Books; New York, NY)

[31] Gosling, Jonathan, and Henry Mintzberg, (2003), “The five minds of a manager”, Harvard Business Review, 1–10.

[32] Schmidt-Wilk, Jane, (2009), “Reflection: A prerequisite for developing the ‘CEO’ of the brain”, Journal of Management Education 33 (1), 3–7.

[33] Roglio, Karina D., and Gregory Light, (2009), “Executive MBA programs: The development of the reflective executive”, Academy of Management Learning & Education 8 (2), 156–173.

[34]Mintzberg, Henry, (2004), “Managers Not MBAs: A Hard Look at the Soft Practice of Managing and the Development of Managers”, (Berrett Koehler; San Francisco, CA).

[34] Pavlovich, Kathryn, Eva Collins, and Glyndwr Jones, (2009), “Developing students’ skills in reflective practice”, Journal of Management Education 33 (1), 37–58.

[35]Looman, Mary D., (2003), “Reflective leadership: Strategic planning from the heart and soul”, Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research 55 (4), 215–221.

[36] Hedberg, Patricia R., (2009), “Learning through reflective classroom practice: Applications to educate the reflective manager”, Journal of Management Education 33, 10–36.

[37] Triandis, Harry C., (1990),“Theoretical concepts that are applicable to the analysis of ethnocentrism”, in Brislin, Richard W. (ed.), Applied Cross-Cultural Psychology: Cross-Cultural Search and Methodology Series (Vol. 14, pp. 34–55; Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA.).

[38] Applebaum, Steven H., Jesse Roberts, and Barbara T. Shapiro, (2009), “Cultural strategies in M&As: Investigating ten case studies”, Journal of Executive Education 8 (1), 33–58.

[39] Varner, Iris, (2001), “Teaching intercultural management communication: Where are we? Where do we go?”, Business Communication Quarterly 64, 99–111.