Research Paper By Deborah Roos

Research Paper By Deborah Roos

(Business Coach, UNITED STATES)

The human body. It’s designed to run like clockwork, each person uniquely cadenced, but all with a similar template. Our temperatures burn around 98.6 degrees F. Our hearts generally beat at a steady rate. Our weight (perhaps with some discipline) finds a natural set point. Even our sleep-wake cycles follow the familiar circadian rhythm. Our bodies prefer homeostasis– a steady, predictable way of being.

Beyond our biology, we even move in steady, predictable ways. People often have a distinctive walk or an expression that etches itself into the owner’s face. This predictability and muscle memory show up in the discipline of practice: throwing, jumping, kicking, swinging. It’s how our greatest athletes, musicians, and even video gamers are made.

But the reality of life is that it changes. A lot. Sometimes those changes are so gradual that we barely notice them such as when a child grows or when a coat of paint becomes no longer fresh. But sometimes change is obvious and large scale such as a company reorg or the ending of a decades-long marriage. And sometimes, as with the COVID-19 pandemic, change overwhelms us: work from home, school from home, wear masks, social distance, don’t shake hands, don’t hug, etc.

Change – the shift from homeostasis – is difficult, challenging, uncomfortable, time-consuming, awkward– a litany of words that generally have a negative connotation. This negativity isn’t an accident or without merit. We are actually hardwired to remain in a status quo state regardless of how favorable a future state may be.

This hardwiring occurs in our brains, the most energy-expensive organ of the human body. But the brain is also programmed to conserve as much of that energy as possible. When able, the brain finds shortcuts or alternatives that often come at an intellectual or behavioral cost to the person employing them.

To illustrate, the prefrontal cortex (PFC), the main processing center of rational thinking, requires significant fuel to regulate itself. When depleted, the PFC gives way to the energy-efficient basal ganglia (a function of the limbic system) whose job is to manage habits. When the PFC checks out and the basal gangliadominates, a desire to eat better is quashed by a habit of snacking in front of the TV (Elation, 2016). With the PFC vacated, the non-rational limbic system – the system responsible for emotional processing and survival instincts – kicks in. Snacking resumes as do our feelings about snacking vs. the goal of eating healthy. And those feelings – frustration, disappointment, guilt – are powerful drivers of behavior, thus illustrating why change is hard.

Further, our energy conservative brains find ways to rationalize away change, even that which we intellectualize as desirable, simply because it requires less work. Psychologist Daniel Kahneman’s Loss Aversion theory describes our tendency to keep what we have (i.e., avoid loss)versus getting something different even if it’s of equal value. For example, emotionally speaking, the pain of losing $10 is greater than the satisfaction of gaining $10. The brain braces against the potential loss, shuttering any gain opportunity – game over; decision made; no more energy required. Loss avoided; change avoided. Further, Failure Bias, or our brain’s assumption that failure is more likely than success, augments the negativity associated with change (Tasler, 2017). Before we even get started, our brain says, “Stay put; it’s easier and safer.” And the brain’s core job is to keep us safe, to protect us from harm, and to ensure our survival. So, change, in whatever form it’s packaged, naturally triggers our fight, flight, or flee responses. By definition, humans seemingly do not want to change.

Yet the conundrum is that we do change, and we want to change. Looking at our evolution and our innovations over the millennia is evidence of that assertion. Imagine how much brain energy has been expended to get us to where we are. The work required for change is the development of new connections between neurons. Creating these connections is called neuroplasticity–a brain with the capacity to be molded or altered. Neuroplasticity is how we learn, how we adapt, how we grow. Creating these new pathways just requires some work.

Coaching, in many cases, is just the kind of work the brain needs to grapple with some of our hardwiring and to build the neuropathways responsible for our development – both personal and professional.

What is it about coaching that helps us to regulate our brains and move us toward our desired goals? By definition, coaching is a solution-focused process that inspires clients “to maximize their personal and professional potential” (ICF). It’s about intentionally moving people forward.“Change” is on the coaching menu from the get-go.

More importantly, the coaching process zeroes in on the exact “weaknesses” of the brain that inhibit forward progress. The limbic system (aka the lizard brain) is all about keeping us safe. When our lizard brain is active – that is, when we are emotional – anxious, confused, frustrated, stressed, angry, nervous — the Prefrontal Cortex isn’t. As such, we quit thinking because we essentially are incapable of doing so. Our energy and our brain’s focus are instinctively determining if or when we should run, engage, or hide. Coaching, by way of the powerful questions that sit as one of its core competencies, gives the PFC something to do: solve a problem, determine an answer. Questions engage the PFC, giving it a job to do; giving the PFC a job tames the lizard brain, restoring dominance of the rational, level-headed PFC. With the PFC properly reinstated, problems shift from a whirlpool of emotions to a more reasoned set of “to-dos.” (Kent and Lee, 2020).

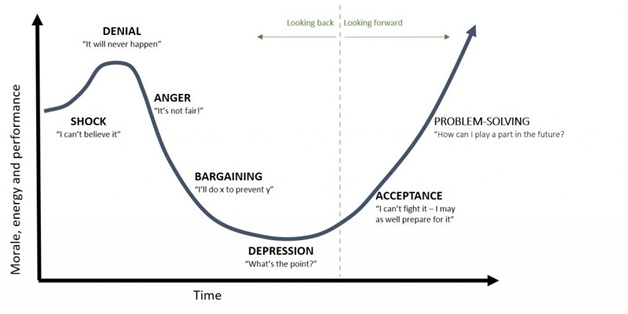

In the business world, giving the brain something to do at the core of change management. According to Prosci – a leader in change tools, training, and experience – change management “help(s) individuals make successful personal transitions resulting in the adoption and realization of change”(Prosci). But to manage something requires that we understand what it is, exactly, that we’re trying to manage. As is human tendency to describe abstract ideas, we build models. One of the most well-known models in this space is the Change Curve.

Google returned 468M hits of the Change Curve, each describing a similar emotional journey: people moving from something to something else, a battle between emotion and logic, and the creation of new neuropathways. The Change Curve is pervasive in the literature of business, and countless variations of the model have been designed to refine and expand its usage and application. Clearly, there’s something to it.

Lesser known (or perhaps acknowledged), as indicated by the mere 162K Google hits, however, is the model’s origin. Introduced in 1969 in her book Death and Dying, Elisabeth Kübler-Ross introduced the five stages of grief experienced by a person approaching death or who has survived an intimate death: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, acceptance. (In 2019 Kubler-Ross’ colleague and coauthor, David Kessler, added a sixth stage to the body of work: meaning.)

Grief. Death. That’s essentially the core of the model the business community has adopted. Yet how many leaders or organizations are actually equipped to deal with their employees navigating the depths of these emotional waters? How many managers understand the root issue of why a new accounting system, or policy change, or team realignment — or the sudden work from home arrangement, or school closure, or lack of social interaction– affects morale, productivity, and teamwork? Grief. Death. This gut-wrenching emotion and sense of finality are apparently at the heart of change.

Author and consultant William Bridges expands upon this idea when he writes:

Change is situational… Transition, on the other hand, is a three-phase psychological reorientation process that people go through when they are coming to terms with change. It begins with an ending—with people letting go of their old reality and their old identity. Unless people can make a real ending, they will be unable to make a successful beginning. (Bridges, 2006)

Change (or to use Bridge’s word, transition), even when it’s good, means leaving something known, something certain for something unknown, something uncertain. Consider a promotion. By most accounts, that’s a win: a higher place on the ladder, recognition for a job well done, the ability for greater influence, more money, and prestige. But it also can stir up feelings of uncertainty, inadequacy, worry: Do I have the skills? What if I can’t do that job? Maybe I was just lucky before and now they’ll find out I’m not that good? What happens if I fail? Perhaps I should decline the promotion….

Renowned social worker, professor, speaker, and author Brené Brown describes what happens in the brain as we consider the gap between our current state and the “to be” state. She says:

In the absence of data, we will always make up stories…Meaning-making is in our biology and when we’re in the struggle, our default is often to come up with a story that makes sense of what’s happening and gives our brain information on how best to self-protect…regardless of the accuracy of the story. (Brown, 258-259)

Because we don’t know for sure what a future state looks like and because our prehistoric limbic brain’s job is to protect us (think T-rex or sabretooth tiger), the stories we make up are emotional and generally worse-case scenarios. Our change “stories,” even in positive situations, are filled with layers of complex emotions that impact our ability to safely make it to the other side.

So how do we change our stories to deal with our emotions of grief, fear, anxiety, and the like to move us toward the right side of the curve? Coaching, in many cases, is the work the brain needs to challenge our thinking and check the validity of how our brains fill in the information gaps.

Coaching is the intentional process of helping clients shift perspectives, see new options, create opportunities, and determine what else is possible. It’s about writing a better draft of the story with a more refined, cogent plot and an understandable set of characters. It’s an experience where the client remains the hero and the primary author of the re-scripting. Author Marion Franklin states, “Change happens only when we receive evidence that proves there are other ways of seeing things;” coaching is the process of providing that evidence. (Franklin, 155)

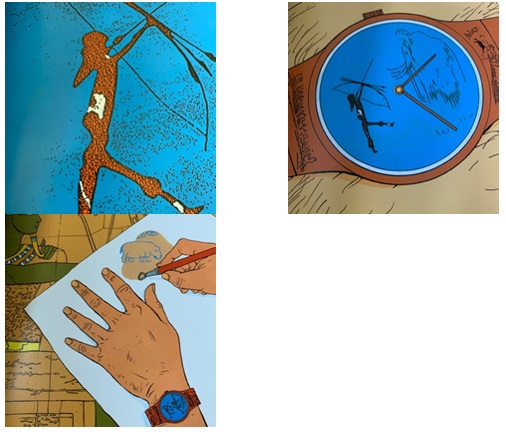

The coaching process – and the unique partnership with an experienced coach –helps people dig into the faulty stories the brain throws together. Shifting perspectives helps us see things from a different angle. The book Re-Zoom by Istvan Banyai provides a great visual example:

By seeing the archer on its own (picture 1), the story we invent might be that it is part of some prehistoric cave drawing. Backing up a bit (picture 2), we have some context – some perspective, and we now understand it’s simply part of a modern-day watch face, which is perhaps (new story) part of a watch ad. With more context (picture 3), the archer is insignificant to the broader story of an archeologist (plot twist –it’s really just a teenager doing a rubbing.). At some point, however, we were vested in “the story of the archer.” Such is the case with our personal challenges: they seem central, detailed, and true. Coaching puts them in perspective and helps modify the storyline, maintaining the logic, but editing in revised pieces of the “truth.”

By seeing the archer on its own (picture 1), the story we invent might be that it is part of some prehistoric cave drawing. Backing up a bit (picture 2), we have some context – some perspective, and we now understand it’s simply part of a modern-day watch face, which is perhaps (new story) part of a watch ad. With more context (picture 3), the archer is insignificant to the broader story of an archeologist (plot twist –it’s really just a teenager doing a rubbing.). At some point, however, we were vested in “the story of the archer.” Such is the case with our personal challenges: they seem central, detailed, and true. Coaching puts them in perspective and helps modify the storyline, maintaining the logic, but editing in revised pieces of the “truth.”

Awareness is another gift available through the coaching process. “I hadn’t considered that” is a frequently expressed phrase by people who’ve been coached. Our brains like certainty, so stories are considered fact. Until they’re not. Coaching challenges our assumptions, opening up the “blind spot” and the “unknown” spaces (Johari Window) about ourselves, others, and the situations we find ourselves in. Awareness helps “unstick” people, providing the fuel to drive us forward. Awareness about self (“I am historically a good learner, so maybe this new system won’t be so hard after all), awareness about others (“Now that I think of it, his attitude has changed since his wife left him.”) and awareness about situations (“I had every intention of leaving the company; now I understand I was just in the wrong job.”)prove to be highly motivating and provide huge forward momentum.

Whereas the Change Curve is the path for people to move from point to point, coaching is the intimate process for their transition. Training, hands-on experiences, and painting the picture of a better future state are effective techniques for making the change journey less jarring. These traditional change efforts effectively put bumpers along the side of the road; coaching, however, helps the client drive through the terrain itself.

Coaching is an essential component of the change and transition management process as it zeroes in on the uniquely human aspect of people grappling with the emotional journey that underpins the situational one. More importantly, coaching is evergreen. It illustrates the proverb: “If you give a man a fish, he will eat for a day. If you teach him how to fish, he will eat for a lifetime.” Change techniques are situation-dependent: training, communication, information, and education are tailored to the unique change event and have to be designed anew each time. An experienced coachee, however, may learn their reluctance is grounded in a set of beliefs or they learn how to shift their own perspective, or they come to realize their initial stories may be faulty; they can apply these lessons to current and future scenarios. By equipping people to manage themselves through myriad changes via the gift of coaching, we empower them to master change – a critical skill set in today’s frenetic business environment.

Mastering change. It sounds magical, and perhaps uber-consultant-y. The reality, however, is that we’re simply tapping into the power of the brain. Coaching gives the brain a chance to do what it does best: learn – “a process that leads to change, which occurs as a result of experience…(that) increases the potential for improved performance and future learning.” (DiPietro). Coaching creates new neuropathways and new neuropathways increase the brain’s neuroplasticity, thus making it ready to take on tomorrow’s challenges.

Bibliography

Banyai, Istvan. (1995). Re-Zoom.

Brown, Brené. (2018). Dare to Lead: Brave Work, Tough Conversations, Whole Hearts.

Bridges, William. (2006). Getting Them Through the Wilderness.

DiPietro, Michelle. How Learning Works: 7 Research-Based Principles for Smart Teaching

DiSalvo, David. (2017). Why is Change Hard

Elation. (2016). Elation Presents: Why Change is Hard

Franklin, Marion. (2019). The HeART of Laser-Focused Coaching.

Gregory, Christina. The Five Stages of Grief: An Examination of the Kubler-Ross Model.

Heshmat, Shahram. (2018). What Is Loss Aversion? Losses attract more attention than comparable gains.

Kübler-Ross, Eabeth. (1969). On Death and Dying.

Lee, Hayden; Kent, Kelly. (2020). “Neuroscience of Resilience” (webinar presentation).

International Coach Federation (ICF).

MacKay, Jory. (2018). Why is Change So Hard? 3Oorganizational Designers Explain How to Beat the Failure Bias

Tasler, Nick. (2017). Stop Using the Excuse “Organizational Change is Hard”