Research Paper By David Kincaid

(Leadership Coach, UNITED STATES)

The lifecycle of many butterflies begins with the deposit of a single egg on the underneath side of a leaf. Soon after, the egg hatches to reveal the larvae; a caterpillar. Because caterpillars are unable to grow with their skin, they may undergo up to five different molting phases, each time revealing a larger and more developed caterpillar. Then, the caterpillar forms a rigid structure around itself, a chrysalis, in which it develops before emerging into the final stage of its life as a butterfly. Humans have marveled for centuries at this incredible process. Children, in particular, are allured by the dramatic changes that occur at each stage of a butterfly’s life. Why is it that we find ourselves drawn to this amazing process? Is it because we find some allure there for ourselves? Perhaps we, too, desire such profound transformation. (“Butterfly school: Metamorphosis, “May 19, 2020.)

In the following, I examine a transformational approach to coaching with a view towards its application in organizations, beginning with an exploration of its definition, followed by a discussion of influential theories borrowed from the discipline of Psychology.

All coaching is and should be, results-oriented. Yet, there is a continuum of coaching models that differ in the approach to those results and the type, or depth, of the results being sought. At one end of this continuum lies Transactional Coaching and on the other, Transformational Coaching. VanderPol’s view, described in his work “A Shift in Being” indicates that there is also an overlapping domain, known as Developmental Coaching, which will not be addressed in this paper, but represents a kind of hybrid model along the continuum. VanderPol addresses these terms as references or approaches to coaching “not styles, methodologies, or niches.” (Vanderpol, 2019, p. 21).

According to VanderPol, Transactional Coaching is “an exchange (or transaction) between a coach and a coachee to achieve clearly defined goals.” (Vanderpol, 2019, p. 23) Change is brought about by “thinking and doing differently.” (Vanderpol, 2019, p. 23) Goals are clearly defined and the coach works with clients to develop techniques, strategies, and solutions to move from point A to point B. Leon uses the idea of an internal operating system to illustrate these distinctions. He compares Transactional Coaching to an upgrade in our operating system to optimize performance or to achieve more. It is surface level and does not dive into the bigger questions of why we do what we do and who we are.

It is important to note that Transactional Coaching, like all coaching, is focused on bringing about an awareness in the client that leads to change. However, though ‘change’ and ‘transformation’ are often used interchangeably, it must be recognized that all transformation is changing but not all change is transformation. A result of a Transactional approach to the coaching relationship may be a change in the client’s strategy, but this is not necessarily sufficient to deem the approach or the outcome as transformational.

Potential coaching clients may see deep dives as risky, that is, threatening to a strongly held way of being, and therefore may shy away from such approaches. In Transactional Coaching, the coach may uncover underlying or limiting beliefs but rarely works with the client to resolve those beliefs, opting instead, to design strategies to achieve the desired goal in the face of self-constructed limitations.

In a survey of the literature around Transformational Leadership and Coaching, VanderPol’s definition represents the gold standard.

Transformational Coaching is focused on enabling self-actualization. Far more than ‘options-strategy-action’ to attain goals or clarity or to get better at something, transformational coaching dives deep into an individual’s psyche, focusing on who the person is and desires to become.… The great transformational question is, therefore, ‘Who do you choose to be?’ (Vanderpol, 2019, p. 28)

What VanderPol’s definition reveals is that Transformational Coaching is ontological, that is, it is about ‘being’ rather than just ‘doing.’ Underlying the approach is the recognition that a shift in being, profoundly influences the choices that are made. As an individual’s way of being shifts, that is to say, transforms into a chosen way of being, so too, do the thoughts, choices, actions, and experiences. Therefore, the intention of the coach-client relationship within the Transformational Coaching approach is to learn about and take action towards those things necessary to grow into the embodiment of that choice in being. A driving question of the Transformational Approach is then, ‘Who do I need to be for my goals or dreams to become a reality?’

With this understanding in mind, it is, therefore clear why the Transformational Coaching approach may not be for every coach or client. There is an inherent deep risk involved in such an engagement. Clients must be willing to risk exposing and subsequently facing “shadowy fears and beliefs” to alter the thought and emotional patterns that have held the client in an old way of being. Consequently, coaches interested in taking on a transformational approach should be well informed and equipped to address this kind of deep emotional risk-taking. Holding space and accountability, in particular, will require more rigorous attention than for transactional engagements.

A more pragmatic illustration of the distinction between Transactional and Transformational Coaching comes from the case study of clients in Allison-Napolitano’s “Flywheel.” In her case study, Allison-Napolitano describes to School District Superintendents, Carrie and Sarah, who seek coaching to a crisis created by divisive teacher teams. Throughout the process, both identified internalized assumptions, which they discovered were at the root of driving the identified problem. Initially, the Superintendents worked with their respective staff to develop leadership growth plans which were rooted in an assumption that the current state of performance was poor and that the targeted outcome should be some future performance improvement. Throughout their coaching work, Carrie and Sarah came to see that by developing leadership success plans and implementing plans early in the teacher engagement, they could honor the teachers’ current performances and convey that the plan was being implemented to ensure continued success. By doing so, teachers’ behaviors and attitudes shifted from animosity and irritability to cooperation and self-confidence. This paradigm shift represents a transformational shift within Carrie and Sarah that was facilitated by identifying and subsequently being freed from deeply held underlying beliefs about the nature of teacher performance. Although there was not a direct resolution of those underlying beliefs, as Vanderpol has suggested, Allison-Napolitano sees this as transformational in that a paradigm shift yielded a successful outcome. (Allison-Napolitano, 2013, Chapter 1)

Origins of Transformational Coaching

Transformational Coaching borrows its term of reference, as well as its theoretical underpinnings, from the field of Psychology. In particular, two behavioral theories serve to inform the transformational approach—Transformational (Adult) Learning Theory and Transformational Leadership Theory.

Transformative Learning Theory:

Jack Mezirow is widely considered the father of Transformative Learning Theory, which seeks to understand how adult learners undergo a significant change in perspective. Mezirow believes that learners utilize meaning schemes—specific beliefs, attitudes, and emotional reactions— as a way of categorizing new information. A change in meaning schemes occurs as learners integrate information into these structures throughout their lives. This incremental process is considered transactional and does not represent a transformative change. Among learners who experience a transformational change of perspective, Mezirow observes, that transformation begins with a disorienting dilemma—a life crisis or some other major life change, whether voluntary or involuntary. Divorce, bankruptcy, severe illness, accidents, death of a loved one, or external occurrences such as recessions, natural disasters, pandemics, or other large scale events are obvious examples. However, less obvious, more existential occurrences can also be considered disorienting dilemmas. Turning 50, or 60, an acute dream, or arriving at a breaking point in one’s stress level at a job may be less overt, but no less powerful, forms of a disorienting dilemma. Following the disorienting dilemma and common process emerges, among those transformed learners that Mezirow studies. This becomes the core framework of Mezirow’s Transformational Learning Theory.

Mezirow’s Transformational Learning Theory Framework

- Disorienting dilemma

- Self-examination

- Sense of alienation

- Relating discontent to others

- Explaining the options of new behavior

- Building confidence in new ways

- Planning a course of action

- Knowledge to implement plans

- Experimenting with new roles

- Reintegration.

Mezirow’s process, therefore, is indicative of a model or approach to adult learning that facilitates the transformation from one set of beliefs, thoughts, and emotions to a wholly new domain; beginning with a disorienting dilemma and ending with reintegration into a renewed sense of normalcy, having transformed. (“Transformative learning,” 2004)

Transformational Leadership Theory:

Whereas Mezirow’s theory focuses on the process by which adult learners experience a transformation in their learning, Transformational Leadership Theory focuses on the attributes that organizational leaders exhibit to inspire those they lead and, ultimately to transform the organization itself. Development of the theory has been predominantly attributed to the researcher Bernard Bass, though Bass expanded on the work of leadership guru James MacGregor Burns. Bass’ work sought to explore the psychological bases for traits that had been documented throughout Burns’ work and career. It is through this exploration that Bass developed the now widely referenced 4 Components of Transformational Leadership (or 4 I’s): Idealized Influence (sometimes referred to as charisma); Inspirational Motivation; Individualized Consideration; and, Intellectual Stimulation. Bass notes that Transformational Leaders exhibit an element of selflessness, choosing to seek the elevation of their followers rather than transforming their leadership styles for self-gain. Such leaders come to embody the expression, “all boats rise.” (“Transformational leadership,” 2005)

Transformational Coaching in Organization Environments

If we coalesce these two dominant psychological theories together with VanderPol’s (and others’) definition of Transformational Coaching it becomes clear that a deeper exploration into the big questions of meaning surrounding the Being of an organization’s leadership can result in the transformation of organizations themselves. This is an exciting domain for a coach interested in Deep Dive engagements. Such coaching interactions hold the possibility of a multiplier effect in that a Transformational Leadership approach, utilizing both Transformative Learning and Transformational Leadership theories, will serve to bring about transformation in their followers. A Transformational Coaching program, therefore, will focus on empowering leaders to empower transformation among followers. In essence, such an approach catalyzing an overall organizational transformation.

An astute coach will develop programs that address not only the intensely personal individual self-inquiry into the deeper essence of Being involved with leadership for a singular leader, but will also develop group coaching activities that will lubricate the way for employees of organizations to achieve self-actualization and create a culture of collective transformation that will undoubtedly lead to a heightened performance in an abundance of measurable domains.

Of particular import is that the coach integrates some variation of Mezirow’s six core elements of transformation into their work with leaders and within organizations. They are individual experience; critical reflection; dialogue; holistic orientation; awareness of context; and authentic relationships. In one particular study, Sammut worked with eight coaches to learn more about how they apply elements of the above to their coaching work. It was found that coaches drew significantly upon all six of Mezirow’s core elements, often without former knowledge of the theory. By bringing more consciousness, that is to say, more intentionality, to the development of organizational interventions that draw upon these theories, Transformational Coaches can drive more successful outcomes incorporate and non-corporate organizations. (Sammut, Kristina, 2014, p. 51-52)

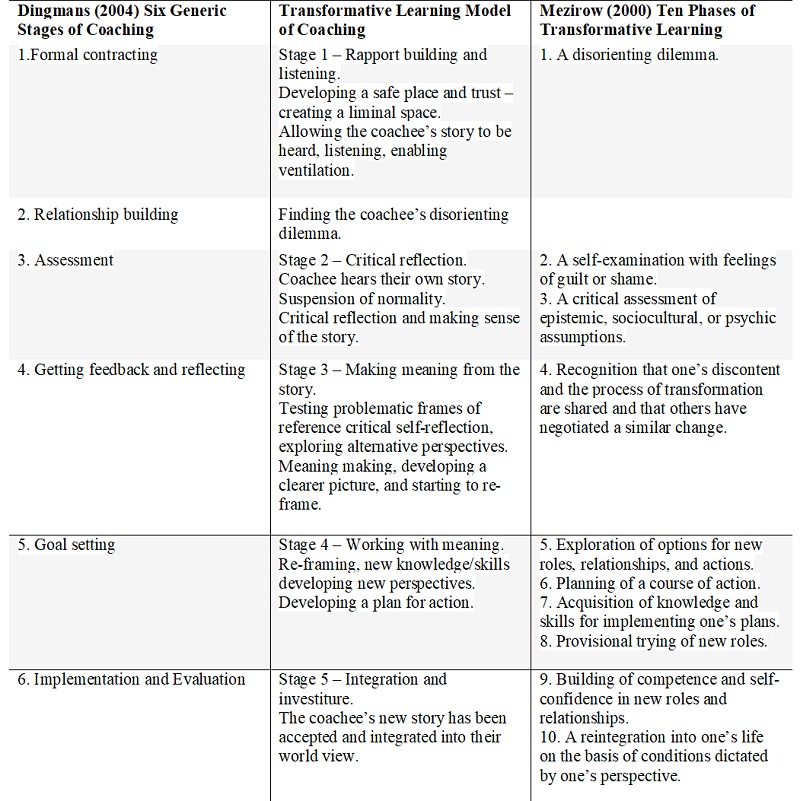

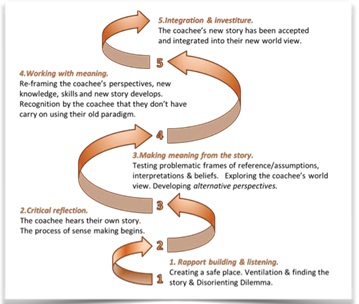

In another study, Corrie and Lawson examined the intersection between Transformative Learning Theory and Transformational Leadership, and propose a general Transformational Leadership Model that honors emergent themes. The study draws upon Dingman’s Six Generic Stages of Coaching, which many may see as reflective of the International Coaching Federation’s (ICF) own list of competencies, to map alongside Mezirow’s Ten Phases of Transformative Learning. The resultant coaching model is indicated by the table and graphic below. (Corrie and Lawson, 2017.)

Table 1 Mapping Dingman, Mezirow, and Transformative Learning Coaching

Table 1 Mapping Dingman, Mezirow, and Transformative Learning Coaching

Figure 1. Proposed Transformative Learning Coaching Model

Figure 1. Proposed Transformative Learning Coaching Model

A critical component of the above model, and one that is intuitively derived by anyone who has worked in the corporate domain, is that the results of such transformation must be measurable for the client to feel as though there has been a success. For this author, in particular, clarifying a transformational model and tapping into some Return on Investment (ROI) potential has been the driver behind this perfunctory investigation of the literature on the subject. Without an ability to measure ROI, any inquiry, no matter how noble the intent, into the deeper questions of personal or corporeal meaning is for naught. This is a necessary and difficult aspect of the Transformational Coaching relationship with both for-profit and not-for-profit institutions. It seems reasonably clear that for-profit, that is to say, private sector, organizations (colloquially known as companies) should wish to validate the effectiveness of an investment into coaching with some verifiable and measurable ROI. What may not be as clear is that not-for-profit or non-profit, Non-governmental organizations (NGOs), donor or foundational organizations, or community groups would also desire such an ROI. When one considers the vast assortment of organizations that exist upon the planet today and simultaneously considers the funding sources for their activities, it would be foolish not to consider how the investment into a Transformational Coach would result in some form of measurable output. After all, organizations, too, must answer to Boards of Directors, donor groups, and constituents regarding the benefits of such “deep dives” into the meaner philosophical questions of Being.

Bruce Avolio, together with Bass, developed an assessment tool know as the Multi-factor Leadership Questionnaire (MLQ) to get at this very question. The MLQ assesses a leader’s style and outcomes and has morphed into what has popularly been dubbed as a 360 review. Appropriate utilization of this tool provides a baseline assessment of leadership and subsequently may use to measure post-coaching improvements in a leader’s style and outcomes. While not comprehensive—a 360 does not necessarily measure organizational improvements—such tools provide coaches assistance with the evaluative process.

The ICF competencies should also be used to support a focus on the development of clear coaching outcomes. Without a clear intended outcome, assessment of actual impacts is fraught with challenges. Especially in the Transformational Coaching domain, coaches should pay special attention to clarifying specific, measurable outcomes for the coach-client engagement so that organizations feel empowered by the resulting outcomes of the professional relationship. In particular, such outcomes should emphasize profit increases, enhancements to organizational morale, improvements in communication, adherence to vision, and advancement in the capacity of employees to engage in organizational efforts. Statistical data and anecdotal interviews can both contribute to the body of evidence demonstrating results.

Today’s world seeks a different effect on its investments. The market is saturated with the Positive Psychology lingo of 30 years ago—it has become farcical—yet, there is a growing minority that holds deeply passionate views about how organizations, corporations, religious institutions, governments and the like should and can participate in the evolution of our human Being. Only Transformational Coaching holds the capacity to inspire such changes in our world today. Yet, the overused rhetoric of transformation threatens the very promise of a brighter future we each hope to achieve. I hope that a more rigorous approach to Transformation will be adopted by the coaching community and that this paper has provided at least some basis upon which this discourse can be founded.

Resources

Allison-Napolitano, E. (2013). Flywheel: Transformational leadership coaching for sustainable change. Corwin Press.

Butterfly School: Metamorphosis. (n.d.). Butterfly School.

Corrie, Ian, and Lawson, Ron(2017). Transformative Executive Coaching: Considerations for an Expanding Field of Research. Journal of Transformative Learning, Vol. 4, No 1.

Sammut, Kristina (2014). Transformative learning theory and coaching: Application in practice. Psychology.

Transformational leadership. (2005, October 26). Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. Retrieved May 23, 2020

Transformative learning. (2004, January 28). Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. Retrieved May 23, 2020

Vanderpol, L. (2019). A shift in being: The art and practices of deep transformational coaching. Imaginal Light Publishing.