A Research Paper By Isabelle Finger, Executive Coach, UNITED STATES

Coach Curiosity in a Coaching Session

In her book “Coach the Person, Not the Problem”, Marcia Reynolds suggests a short meditation for coaches to do before each session. The flow of the exercise is to engage the brain, the heart, and the gut[1]. I’ve adapted her exercise to ignite my “3 C’s”: Curiosity (the Mind), Care (the Heart), and Courage (the Gut). I’ve seen the difference it makes in my coaching sessions when I do practice that exercise – and when I don’t.

In this research paper, I’m going to focus on a very specific aspect of the first of the “C’s”: the curiosity of the coach in a coaching session. To do so, I will look at two main questions: What is curiosity and how can coaches best leverage it in coaching sessions?

What Is Curiosity?

If we were to write a list of key characteristics of human behaviors, curiosity would be ranked among the highest items. While some proverbs and idioms try to warn us about the dangers that curiosity can trigger if used unwisely (“Curiosity kills the cat”), philosophers and psychologists recognize it as a key driver of human development and a basic element of human’s cognitive mechanisms. Lately, the business world has put curiosity on the list of most valuable soft skills because of the development of the service industry in an environment that has become more volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous[2].

Given the ubiquity of curiosity in our lives and the (mostly) positive resonance of it[3], we could believe that plenty of researchers has “cracked” it and that the phenomenon is well defined and well understood. Despite a strong interest in curiosity from leading psychologists in the late 19th and early 20th century (e.g., Ivan Pavlov), it is only recently that psychologists and neuroscientists started to develop an integrative theory of what curiosity is, which forms it takes, why it exists, and how it works. As of today, many aspects of curiosity remain unclear – curiosity about curiosity has a long and promising future!

George Loewenstein offers in 1994 a definition of curiosity that has been very influential since then:

A cognitive induced deprivation that arises from the perception of a gap in knowledge and understanding[4]

This definition differentiates curiosity from information-seeking, described as the search for more or better information to optimize a decision. It also describes curiosity as an intrinsic drive while information-seeking is seen as extrinsic motivation.

However, it is not always possible to know if people acted out of intrinsic or extrinsic motives and a solid and largely adopted taxonomy of curiosity remains to be elaborated.

This doesn’t however prevent us from looking at curiosity through different lenses. In their article, Celest Kidd and Benjamin Y. Hayden suggest using Tinbergen’s Four questions[5]. For the scope of this research paper, we will focus on two of them[6]: What is the function of curiosity and how does it work?

What Is the Function of Curiosity?

A certain consensus dominates in the scientific world regarding the benefit of curiosity for human beings. In a context where information provides value to those who can use it, human beings have developed the capacity to learn. Curiosity is nothing else than the motivation to learn (as thirst is the motivation to drink). This theory assumes that once the individual has gotten enough information, their curiosity level will decrease[7].

Supporting learning through curiosity is a fundamental pedagogical concept and finds more and more adepts within professionals who develop educational content. By asking learners to find some information by themselves (aka using their curiosity), the learning effect (including memory) is stronger than if they were presented with all the information from the beginning.

How Does Curiosity Work?

Curiosity seems to be triggered by two main situations[8]:

- Deprivation of information and research of stimulation (for instance when we are experiencing boredom)

- When something conflicts with our worldview or when something denotes novelty, complexity, uncertainty[9]

The mechanisms linked to curiosity at play in the human brain are still largely mysterious and seem to be more complex than some other pleasurable activities. Recent research shows that[10]:

- While some of the reward mechanisms are activated when people are in a state of curiosity (brain activity in the caudate nucleus and the inferior frontal gyrus, dopamine), other reward mechanisms remain surprisingly inactive (nucleus accumbent).

- The reward signal (dopamine) not only translates satisfied curiosity but varies according to both the value of the information and the cost or risk linked to the activity of getting the information.

- Learning and memory mechanisms are triggered by a state of curiosity (parahippocampal gyrus and hippocampus)

We mentioned already that research about curiosity still has a long path to better clarify, describe, and understand this phenomenon. One aspect that is striking regarding the scope of this research paper is that the existing research assumes that curiosity is driven by some sort of self-interest. In the diverse experiments, the subjects are trying to get information and learn to be better off for themselves. In coaching, however, curiosity is a tool used by the coach at the service of the client rather than a mechanism to benefit the coach directly. We will see in the next chapter how this caveat is crucial to keep in mind while deploying curiosity in a coaching session.

How Can Coaches Best Leverage Curiosity in Their Sessions?

At the core of the coaching philosophy is the belief that the clients can find the best solutions and next steps for themselves. The coach’s role is to ask questions to foster awareness, perspective shifts, broaden horizons, and foster learning.

To be impactful, the questions can’t be standard. They need to adapt to the situation, to the client’s personality, to the flow of the session. If the coach can’t rely on a predetermined list of questions, the only resource they possess to ask powerful questions is their curiosity.

As we have seen before, curiosity remains a complex phenomenon to define. This is also true in the coaching context, and this opens the door for many pitfalls.

The Pitfalls of the Coach’s Curiosity

First, and as highlighted by Marion Franklin in her book “The Heart of Laser-Focused Coaching”[11], the intent behind curiosity is not for the coach to learn more about the story of the client. It is important to be aware and on the lookout for such a pitfall, because:

- It is sometimes tempting to learn more about a “juicy” situation

- By asking questions about the story, the coach takes the risk of spending the precious time of the session going through the meanders of complicated descriptions instead of focusing on what the client thinks and feels and how change can happen.

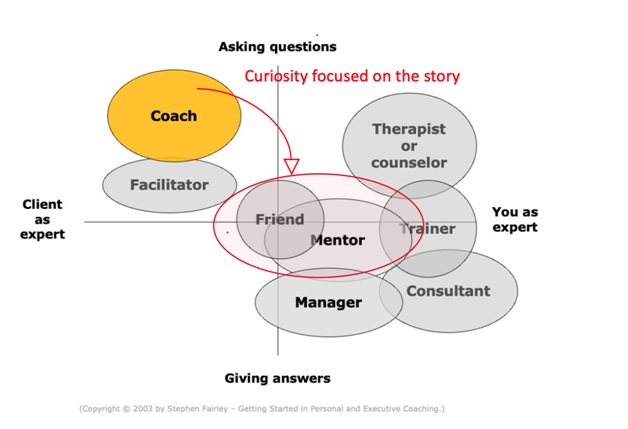

Both can negatively impact the coaching session. On one hand, the client can feel overwhelmed (again) by the complexity of the situation and lose the confidence that progress can be achieved. On the other hand, they can lose trust in the coach as they might see the questions as intrusive or be annoyed to have to dive into extensive details that seem obvious to them. The coach can also be overwhelmed by the details and the intensity of the story. They can lose the distance that differentiates empathy from sympathy and feel pressure to find solutions for the client. In doing so, the coach refuses to believe that the client is the expert in the relationship and takes on that role. In the best case, the coach is behaving more like a friend or a mentor who is emotionally involved in the situation and tries to give well-intentioned advice. In the worst case, the coach is behaving like an intruder indulging “nosey” curiosity.

This move can be depicted using the framework of Stephen Fairly in his book “Getting Started in Personal and Executive Coaching”[12]. In the graph below, the author provides a visualization of the differences between a coach and many other roles, according to two dimensions: the methods of communication (asking questions vs. giving answers) and the positioning (expert vs. client as an expert). The red circle and arrow show how curiosity focused on the story can let the coach “slip” to another type of role.

Second, the coach’s curiosity should not focus on finding the best way to make a point, prove the client to be wrong, or lead the client to a specific endpoint. The coach needs to be on the lookout to avoid applying curiosity to the aspects that could validate their assumptions about the “best solution” for the client.

Life Example 1:

My client Beatrice was speaking about her anxiety regarding her job search and the answers she will be getting soon from companies where she had applied. At some point, she mentioned that she was not in control of the responses she would get from those companies. A feeling of anxiety and of lack of control – that sounded like a promising and logical avenue to explore! At that moment, my thoughts as a coach were: “Ah! That’s it! Let’s go down that road, she will have an “ah-a” moment and I will feel good about a strong coaching session”.

As I caught myself having such a thought, I brought myself back to the principle that the only thing that I know is that I don’t know anything. Hence, instead of asking questions about how this lack of control was affecting her reality, or how she could fight against this lack of control, I took a step back and asked about how she was differently experiencing situations where she did her best but was not in charge of the final decision. This question gave her the space to realize that it was not so much about being in control, but rather about giving too much significance to the outcome. She was then able to envision how to change this mindset.

Thirdly, we saw that satisfying curiosity is rewarding (dopamine increase in the brain, activation of some parts of the brain – see part I). It is important for the coach to not engage in a reward-looking curiosity. Discovering a piece of new information, being intrigued by a body language or a change in energy should not be considered as a “kick” by the coach. If this is the case, the main focus of the session is not the client anymore. The client is then relegated as an excuse for the coach to focus on self-interest. Such behavior is more likely to bubble up when the topic of the session is very close to the coach’s own experience.

Life Example 2:

In one of my sessions, my client spoke about the soon-to-come publication of his book. He mentioned to me that the book was about leadership and that his concepts were anchored in his childhood on a farm. Immediately, I pictured my childhood in Switzerland when I was guiding the cows to the mountains in the Summer. I was dying to know more about the book and his experience and to share with him that we had this in common. It required my full willpower to put that thought aside and refocus on the agreement and the flow of the session.

How to Use Curiosity in Alignment With the Principles of Coaching?

With so many pitfalls, what can the coach do to ensure that their curiosity is aligned with the principles of coaching?

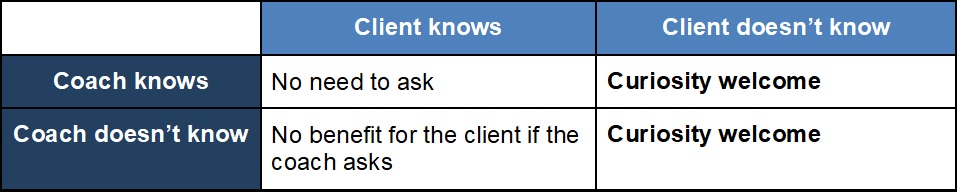

First and foremost, the coach needs to always keep in mind that their role is to act for and only for the interest of the client. The coach should not try to enjoy a juicy story, be the hero, or find insights for their own life. A useful tool to do so in the following 2 by 2 matrix:

If the coach can embrace this kind of altruistic curiosity, they have at their disposition a magnificent tool to enhance sessions. As Lindsay Dotzlaf says in her podcast “Mastering coaching skills”[13];

If the coach can embrace this kind of altruistic curiosity, they have at their disposition a magnificent tool to enhance sessions. As Lindsay Dotzlaf says in her podcast “Mastering coaching skills”[13];

Curiosity is a remedy against assumptions and judgment.

This implies that the coach is not answering their questions in advance and is not attached to the answers given by the client.

It also implies that the coach should choose altruistic curiosity whenever possible even if it means entering the unknown and, as a consequence, represents some risks.

Life Example 3:

One of my clients tends to become emotional and cry in most of our sessions. Once, as we were discussing one of her key topics, I remember thinking: “I should ask this – but if I do, she is going to cry…. maybe I can find another question”. It was very tempting for me to try to avoid the uncomfortable situation, but then I asked myself what my client needed. And having worked with her a few times, I knew that tears were part of the process and that she would come out stronger and with a broader awareness about herself. So, I asked. I was right about the tears; I was also right about the impact of the question on her new awareness.

To implement such principles in sessions, Csikszentmihalyi gives us a methodology. He stated in his book “Flow”

We can develop our curiosity (and fight boredom) by making a conscious effort to direct our attention to something in particular in our environment.” So, if we direct our attention fully to our clients and become explorers, curious as to what we will discover together, this will enhance our ability to even BE curious! [14]

I tend to apply curiosity when I perceive a dissonance in body language, tone of voice, energy, types of words, or logic. I also try to ask what is missing.

Life Example 4:

One of my clients wanted to make journaling a habit. She was procrastinating even if she perfectly knew and recognized the positive impact that journaling would have on her life. In our session, she made some progress in terms of awareness of her challenges and in shifting her mindset. She was telling me that she was going to journal more. However, her voice was slow and not energized. I reflected her that she seemed more convinced but that she didn’t seem to be looking forward to her journaling and asked what she thought about my comment. She laughed and admitted that while she was rationally convinced about the necessity to journal, her motivation, and envy to do so we’re still at a very low level. We took it from there and added another 30 min to the session before she felt motivated. Without my question, we might have ended the session too early and not gotten a real change in her mindset.

The Coach Curiosity Is One of the Key Engines of Any Impactful Session

Human beings were blessed with the gift of curiosity (which doesn’t mean that other animals are not curious!) and this phenomenon plays a crucial role in the individual’s development and life in general. For the coach, curiosity is one of the key engines of any impactful session. To use it wisely and in alignment with the principles of coaching, the coach needs to be aware of some pitfalls that might happen and can easily derail the session, as well as the whole relationship with the client. By keeping the client at the center of the session and their interest in check, the coach can leverage the power of curiosity. For me, this is where I see the wisdom of the short meditation suggested by Marcia X and that I adapted to my “3C’s: Curiosity, Care and Courage”. Caring for the client ensures that my curiosity serves them and not myself. Courage ensures that I don’t shrink back from a risky or uncertain situation if I think that the client can benefit from the question.

References

Marcia Reynolds, “Coach the Person, Not the Problem”, Berrett-Koehler Publishers

Francesca Gino, “The Business Case for Curiosity”, HBR September-October

Celest Kidd and Benjamin Y. Hayden, “The Psychology and Neuroscience of Curiosity”

Josh Clark, “How Curiosity Works”, HowStuffWorks

Marion Franklin, MS, MCC, “The Heart of Laser-Focused Coaching”, Thomas Noble

Stephen Fairley, “Getting Started in Personal and Executive Coaching: How to Create a Thriving Coaching Practice”

Lindsay Dotzlef, “Mastering Coaching Skills”, Podcast - episode 53

Pamela Richard in “Curiosity, a Key Element of the Coaching Approach”