Coaching for Flow: facilitating flow in the client’s everyday experience

The second type of interventions mentioned above, i.e. those attempting to assist individuals in finding flow (Nakamura & Csikszentmihalyi, 2002), can be applied to the coaching process. This could be called coaching for flow, aiming at transforming the everyday experience of the client by increasing the frequency of flow experiences. This is another objective at which the “flow enhancing model of coaching” of Wesson & Boniwell (2007) aims.

In the previous sections the elements boosting and characterizing flow have been described in detail. In this section the same elements will be presented from a coaching process perspective, providing examples on how coaches can use these elements to foster flow in the client’s everyday experience.

With reference to the conditions of flow (Csikszentmihalyi, 1975; Nakamura & Csikszentmihalyi, 2002; Csikszentmihalyi, Abuhamdeh, Nakamura, 2005), below are provided some examples on how the coach can support clients to find their own-way to access flow.

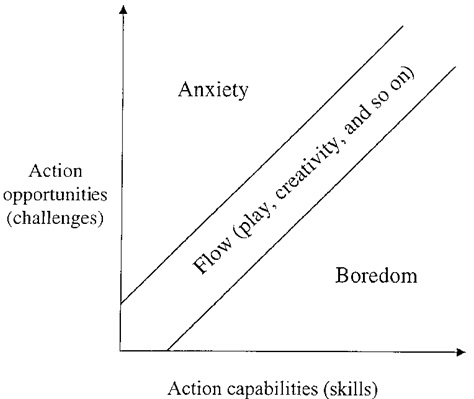

Figure 1: The original model of Flow State

Source: Nakamura & Csikszentmihalyi (2002).

Source: Nakamura & Csikszentmihalyi (2002).

The coach can help the client to understand these mechanisms and find his/her way to reach conditions of flow, limiting anxiety and boredom.

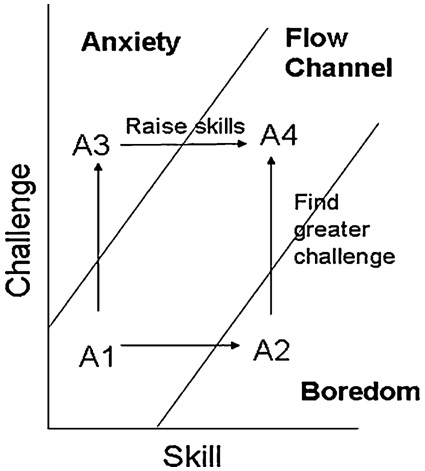

To coach for flow, the coach can support the client in either increasing skill level, if the client is, for instance, in a condition of anxiety, or to increase the level of challenge, if the client is in a condition of boredom (Kauffman, 2006). The coaching process supporting the client to move from anxiety to flow can consist in helping clients reduce challenge by breaking the task into smaller pieces, and building up skills until the client feels ready to manage the task or situation (Kaufman 2004 b). On the contrary, if the client is experiencing boredom, the coach can help the client in identifying ways to increase the level of complexity and to enlarge the vision of the client on the project or task at hand (Kaufmann 2004 b). In both situations, the coaching process assists the client in increasing his or her skills and in further growing and developing, in addition to enhancing the quality of the client’s experience.

Britton (2008) explains how she uses the flow diagram reported below (Figure 2) as “a visual aid in job coaching discussions between employees and supervisors”. When people are in boredom and anxiety states in working environments, they start to be disengaged and search for satisfaction elsewhere. A supervisor can work with the employee to understand where he/she is in the visual proposed, and work with the employee to understand how to change things to reach a condition of flow (Britton, 2008).

Figure 2: Flow channel

Source: Britton (2008), reprinted with permission from Csikszentmihalyi (1993, p. 70).

Source: Britton (2008), reprinted with permission from Csikszentmihalyi (1993, p. 70).

The coach can help the client to understand the intrinsic motivation which makes the activity at hand enjoyable. In case the client can not find easily an intrinsic motivation, the coach can help the client identify aspects of the challenge that are intrinsically rewarding. According to Davies (2009) people are more likely to be intrinsically motivated and to maintain intrinsic motivation when the task fulfils three of the basic psychological needs, thought to be essential to human motivation and growth, i.e. autonomy, relatedness, and competence.

Conclusions

The research conducted suggests that there are many potential applications of the flow theory to coaching, both in coaching conversations and in the coaching process, to increase the frequency of positive flow experiences in clients’ lives. Further research on flow application to coaching is needed. One possible area of further development could be analyzing the phenomenon of “social flow” and its potential application to group and team coaching.

Bibliography

Britton K., 2008, “Increasing job satisfaction: coaching with evidence-based interventions”, Coaching: An International Journal of Theory, Research and Practice,1:2, (pp.176-185).

Buzan T., Buzan B., 2003, “The mind map”. London: BBC Worldwide Limited.

Cameron S., 2001, “The MBA handbook – Study skills for postgraduate management study”. Harlow, England: Financial Times: Prentice Hall.

Csikszentmihalyi M., 1975, “Beyond boredom and anxiety”, San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Csikszentmihalyi M., 1993, “Flow. The psychology of optimal experience”, New York: Harper Perennial.

Csikszentmihalyi M., 2004, “Good business: Leadership, flow, and the making of meaning”, New York: Penguin Book.

Csikszentmihalyi M., 2008, “Flow. The psychology of optimal experience”, Harper Perennial Modern Classics.

Csikszentmihalyi M., Abuhamdeh S., Nakamura J., 2005, “Flow”, Chapter 32, in Handbook of Competence and Motivation, edited by Elliot A. J. & Dweck C.S., The Guildford Press.

Davies W., 2009, “Self Determination Theory – Finding the right kind of motivation”, http://generallythinking.com/self-determination-theory-finding-the-right-kind-of-motivation-2/

Friedman W. J., 1990, “About time: Inventing the fourth dimension”, Cambridge, MA, MIT Press.

Greenwald A., 1982, “Ego task analysis: An integration of research on ego-involvement and self-awareness”, in A. H. Hastorf & A. M. Isen (Eds.), Cognitive social psychology (pp. 109-147). New York: Elsevier/North Holland.

Harackiewicz J. M., Manderlink G., 1984, “A process analysis of the effects of performance-contingent rewards on intrinsic motivation”, Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 20, (pp. 531-551).

Harackiewicz J. M., Elliot A. J., 1998, “The joint effects of target and purpose goals on intrinsic motivation: A mediational analysis”. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 24(7), (pp. 675-689).

International Coaching Federation, “Code of Ethics”, http://www.coachfederation.org/ethics/.

Kauffman C., 2004a, “Multi modal coaching”, Third Annual International Summit of Positive Psychology, Washington, DC.

Kauffman C., 2004b, “Pivot point coaching”, Annual Meeting of the International Coaching Federation, Quebec, Canada.

Kauffman C., Scouler A, 2004, “Towards a Positive Psychology of Executive Coaching”, Chapter 18, in Linley & Joseph (Eds), Positive Psychology in Practice. New York: Wiley Press.

Kauffman C., 2005a, “Pulling it all together: Developing and organizing positive psychology interventions”. Fourth Annual International Summit of Positive Psychology, Washington, DC.

Kauffman C., 2005b, “The dialectics of peak performance”. Psychology Lecture Series at McLean Hospital, Belmont, MA.

Kauffmann C., 2006, “Positive Psychology: The Science of the Heart of Coaching”, Chapter 8, in D. R. Stober & A. M. Grant (Hrsg.), Evidence Based Coaching Handbook: Putting Best Practices to Work for Your Clients (pp. 219-254). New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Nakamura J., Csikszentmihalyi M., 2002, “The concept of flow”, in C.R. Snyder & S.J. Lopez (Eds.), Handbook of positive psychology (pp. 89–105), New York: Oxford University Press.

Polit D. F., Hungler B. P., 1991, “Nursing Research: Principles and methods”, Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott Company.

Rathunde K., 1989, “The context of optimal experience: An exploratory model of the family”, New Ideas in Psychology, 7(1), (pp. 91-97).

Sansone C., Sachau D. A., Weir C., 1989, “Effects of instruction on intrinsic interest: The importance of context”, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57(5), (pp. 819-829).

Wesson K., Boniwell I., 2007, March, “Flow theory – its application to coaching psychology”, International Coaching Psychology Review, Vol. 2 No. 1, (pp. 33-43), The British Psychology Society.

Wesson K., 2010, “Flow in coaching conversation”, in International Journal of Evidence Based Coaching and Mentoring, Special Issue N. 4, October, (pp. 53-64).

[1] This is defined as “an approach to collecting and analyzing qualitative data with the aim of developing theories and theoretical prepositions “grounded” in the real-world observations” (Polit & Hungler, 1991).