Research Paper By Cheryl Ewing

Research Paper By Cheryl Ewing

(Health and Wellness Coach, NETHERLANDS)

Overuse injuries are elusive and often develop well before physical complaints (1). Generally, there is a gradual increase or stacking of symptoms and the athlete is unaware that they are injured until much further down the line when the physical injury is quite substantial. This creates a difficult setting in which physical and psychological challenges may affect future performance and recovery (2). Commonly, athletes retrospectively try to understand the cause of the injury and form their own values and belief system around the etiology of the injury and the prevention or management of further injury (1). This retrospective learning coupled with the insecurity regarding their identity and future return to sport causes a turbulent period in which the athlete loses their identity, their social connections, and their daily routine.

An overuse injury is defined as the absence of a single, identifiable cause to muscle, ligament, or bone (1). When the musculoskeletal system is exposed to repetitive load over and above its ability to cope, microtrauma ensues which eventually leads to a state of disrepair and dysfunction. A low level of inflammation, repair processing, and adaptive responses in the bone or soft tissue architecture is the bodyś best attempt at healing. Although effective, it is still not enough to overcome the repetitive load placed on it and the musculoskeletal tissue fails. This results in pain, dysfunction, and an inability to continue participating in oneś chosen sport. Over a quarter of all injuries in sport are overuse injuries (2). Also, women are at greater risk for overuse injuries than men with the lower limb more commonly affected (2). Typical overuse injuries include tendinopathy, bursitis, and bone stress syndromes and are treated both conservatively and/or surgically (2). The Conservative approach is most often utilized as the primary management technique as it is non-invasive and safer for the individual however, conservative management fails in about ¼-⅓ of cases and this results in a surgical intervention (1). With this in mind, both conservative and surgical management can result in long rehabilitative periods spanning several weeks to months.

Participation in Sport often goes far beyond the physical benefits that one would assume to be the primary reason for participation. Many athletes have not developed an identity outside their chosen sport and rely on the sport as a sense of identity and community (4). In essence, sport becomes a major component of their self-identity and an outlet for dealing with stress and other underlying psychological issues (3).

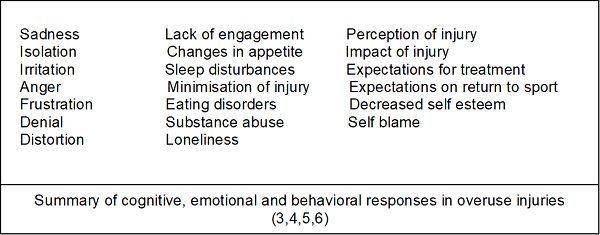

For many athletes, an injury is perceived as a major life event; and therefore has the ability to affect the cognition, behavior, and emotion of the individual (3). The athlete fears injury and therefore tends to ignore the earlier signs of dysfunction opting to push past the pain and continue. Once the athlete has realized that the injury is beyond their coping mechanisms and their performance starts to suffer, athletes still avoid seeking treatment. There is a tendency towards the mindset of denial, distortion, and minimization of the injury when confronting themselves, their coaches, and their team members and family members (2). Athletes remain in a frozen state of avoidance, whereby they do not have the appropriate tools to support the process of acknowledgment and the mental and emotional maturity to accept the injury and move to a place of action and accountability. As injuries cause a sudden imbalance or interference with the lives of athletes; most particularly their health, the achievement of athletic potential and perception of their community and peers; a loss of identity, isolation from one’s team and community, fear around the injury and return to sport, loneliness and lack of optimism and self-efficiency are common themes in an injured athlete’s mindset (3,5,6).

The psychological perspective of the athlete can be divided into 3 key stages; The initial, the rehabilitative, and the reintegration stage.

The initial stage:

In the initial phase injury, the athlete displays behaviors of avoidance and denial. They do not want to confront the reality that their body has been compromised and that they are unable to train and perform at the level that is required by themselves, their peers, and their coaches. Athletes are often irritable, angry, and suffer feelings of isolation as they begin to distance themselves from the reality of the situation and their society in more general terms. During the initial phase, there is a gradual loss of identity as the athlete struggles to come to terms with the injury.

The rehabilitative stage:

The rehabilitative stage occurs when the athlete acknowledges the injury and begins to seek medical treatment for the injury. This may include the coach, doctors, specialists, and physiotherapists. During this phase, the athlete may struggle with emotions such as fear of the unknown, guilt, and self-blame for what has happened and decreased self-esteem. The athlete may have unrealistic expectations of the injury and/or treatment and may struggle with the motivation for the rehabilitative process and general wellness. All this is confounded by the loneliness and isolation the athlete feels being distanced from their team, sport, and community.

The reintegration stage

The reintegration phase which includes returning to sport is a complicated time for the athlete. It is a time marred with self-doubt, pressure, and fear. The athlete wants to return to sports injury-free but may be concerned about reintegrating back into team dynamics, reinjury, returning too early or the pressure to resume a full workload. Self-doubt and lack of confidence are strong emotional triggers during this phase. The rehabilitation of an athlete following injury is largely dependent on the physical recovery and rehabilitation of the athlete as well as the cognitive and emotional readiness of the athlete to return to sport. Advancement in medical science and technology has reduced physical healing times considerably and has allowed athletes to reintegrate back into sport far quicker than previously (5). However, the psychological well-being of the athlete has not received as much attention and although many institutions have begun to integrate psychological support into their rehabilitation programs, the focus of rehabilitation is still very much centered around the physical wellbeing of the athlete rather than the psychological (5). This imbalance of physical and psychological support of the athlete following injury may negatively impact the athletes’ ability to recover from injury and return to sport efficiently and effectively without consequences. Coaching may provide the psychological interventions and support that is lacking and reduce the potential discrepancy between physiological and physical recovery allowing the athlete to return to support the psychological and physical readiness required for successful reintegration.

The implication of Coaching in the management of injuries

What is coaching?

Coaching is a form of growth and development of an individual or client (7). It is a partnership that supports the client at multiple levels in realizing and unlocking their true potential in becoming who they are meant to be (8). Often the client experiences feelings of being stuck, frustration, and a seesaw of emotions about a topic or situation that they have no resolution for (9). Coaching allows the clients to shift their perspective and develop a path to discovering different ways of achieving their goals. Growth and awareness are achieved using a large array of coaching techniques and communication skills by the coach that assists the client in raising awareness, empowering choice, and unlocking potential to achieve personal or professional goals specific to them (8). Common forms of communication techniques include targeted restatements, active listening, questioning, and clarifying (7).

There are several benefits of coaching in the context of athletes experiencing chronic injury and withdrawal from the sport during healing and rehabilitation. Most notably, the coach forms a vital link between the athlete, the coach, and the medical team. Coaches, supportive parents, medical teams, or teammates; may often have another agenda that may influence the decision-making process, management, and support of the athlete. The athlete may not feel confident in talking about their fears, frustrations, or concerns in a space that is not purely focused on themself and their condition. A coach is impartial and without agenda or judgment. A safe and supportive environment for the athlete to express themself freely to an unbiased sounding board, free from prejudice and opinion. Space where the athlete can make empowering choices and develop goals that service their true values and beliefs.

Secondly, the coach creates an environment of trust and intimacy, one of the core competencies as defined by the International Federation of Coaching (ICF). Trust allows the athlete to be their genuine self without fear of judgment or mistreatment. Once trust is established, coaching becomes a highly effective and efficient tool in allowing the athlete to reach their objectives and goals.

Finally, coaching allows the athlete autonomous motivation. Autonomous motivation is defined as engaging in a behavior because it is perceived to be consistent with the intrinsic goals or outcomes and emanates from the self (9). By supporting an athlete in making decisions and goals from a place of personal choice and endorsement, the athlete will feel empowered and committed to their goals. Individuals acting in this autonomous capacity are more likely to initiate, commit to, and persist with their behaviors (9).

Several coaching tools have proven to have a good effect on supporting athletes with injuries. The following tools resulted in improved psychological coping skills and flexibility decreased re-injury anxiety and decreased emotional and psychological disturbances(6).

Visualisation/imagery:

Visualization is defined by the Oxford dictionary as the act of forming a picture of something in your mind. This practice of imagery allows the athlete to connect the mind with several phases within the healing process incorporating emotional, mental, and physical awareness, to direct focus to the healing of the body through the mind’s eye and to envision the successful return to sport and competition.

ACT intervention:

ACT is a cognitive behavioral therapy that places focus on mindfulness and psychological flexibility and has received considerable interest in literature in supporting injured athletes. ACT allows the athlete to connect with themself in the present moment and in doing so, allows the athlete to make positive behavioral changes to support their rehabilitation

Microcounseling/Written expression:

Microcounseling utilizes tools such as active listening, empathy, and reflection to support the athlete’s wellbeing.

Written expression enables the athlete to understand and gain control of their emotional state through descriptive writing.

Goal setting:

Goal setting is the development of an action plan that motivates the athlete to move effectively towards the desired goal with focus and persistence. The athlete is actively involved in the process of recovery and the direction of their future which empowers the athlete through self-confidence and self-efficacy.

Relaxation/deep breathing:

Both relaxation and breathing techniques lower the heart rate and blood pressure, therefore, enabling the athlete to move into a state of conscious decision and focus on what is real and important as opposed to decision making from a place of anxiety, uncertainty, and fear.

In summary, overuse injuries may have profound negative consequences on the mental and emotional state of athletes. Feelings such as anger, fear, avoidance, and decreased self-confidence are just a few of the psychological implications of overuse injuries (5). The inclusion of psychological support during the initial, rehabilitation, and reintegration phases may positively affect the athlete and reduce the time required to return to sport. This positive psychological influence may further support the athlete as physical healing times decrease due to the advancement of medicine and more and more pressure is being placed on the athlete to return to sport. Although there has been increasing attention drawn to the role of psychological support in athletes following a sports injury, research remains largely limited and there is a significant lack of well-designed intervention studies targeting this area (5). Further investigations into the psychological support and intervention of post overuse injury outcomes may significantly impact athletes in returning to sport.

References:

The article, R., Tarantino, D. & Maffulli, N. Overuse injuries in sport: a comprehensive overview. J Orthop Surg Res 13, 309 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13018-018-1017-5

Yang J, Tibbetts AS, Covassin T, Cheng G, Nayar S, Heiden E. Epidemiology of overuse and acute injuries among competitive collegiate athletes. J Athl Train. 2012 Mar-Apr;47(2):198-204. DOI: 10.4085/1062-6050-47.2.198. PMID: 22488286; PMCID: PMC3418132.

Psychological Issues Related to Illness and Injury in Athletes and the Team Physician: a Consensus Statement—2016 Update, Current Sports Medicine Reports: 5/6 2017 – Volume 16 – Issue 3 – p 189-201 DOI: 10.1249/JSR.0000000000000359

Reese, Laura M. Schwab, Ryan Pittsinger, and Jingzhen Yang. “Effectiveness of psychological intervention following a sports injury.” Journal of Sport and Health Science2 (2012): 71-79.

Von Rosen P, Kottorp A, Fridén C, Frohm A, Heijne A. Young, talented and injured: Injury perceptions, experiences, and consequences in adolescent elite athletes. Eur J Sports Sci. 2018;18(5):731-740. DOI:10.1080/17461391.2018.1440009

https://internationalcoachingcommunity.com/

Shuer ML, Dietrich MS. Psychological effects of chronic injury in elite athletes [published correction appears in West J Med 1997 Apr;166(4):291]. West J Med. 1997;166(2):104-109.

Dijkstra HP, Pollock N, Chakraverty R, et al managing the health of the elite athlete: a new integrated performance health management and coaching model British Journal of Sports Medicine 2014;48:523-531.

van Wilgen CP, Verhagen EA. A qualitative study on overuse injuries: the beliefs of athletes and coaches. J Sci Med Sport. 2012;15(2):116-121. DOI:10.1016/j.jsams.2011.11.253