A Research Paper By Karin-Ann Holley, Life Coaching for Educators, NETHERLANDS

Addressing Burned Out Educators

A Study of Burnout in Education: The Causes, Symptoms, Trends, Effects, and Some Solutions

The educational sector, in many countries around the world, is in crisis. The COVID pandemic has exacerbated a trend that was already present among educators[1]: increased levels of stress and burnout. A few of the challenges educators have had to face these last two years are teaching in blended learning environments, having to deal with constant changes to policies and procedures, health and safety fears, supporting students with increased mental health issues, and communicating with worried parents.

In many countries, the low status and salaries of teachers don’t help the situation. Because they are being overworked and underpaid, teachers are retiring early and others are leaving the profession, increasing teacher shortages in many countries around the world. This fact puts more pressure on the remaining teachers, and so the cycle of stress and burnout continues.

Solutions for decreasing educator stress levels can be found on many levels. For example, improving national and state policies and funding, decreasing class sizes, and the number of classes taught would make the teaching profession more alluring. At a school level, carefully looking at ways to decrease the workload, creating a supportive and positive school culture and community, incorporating mental health days, and offering counseling and coaching as professional development options, to name a few.

The Research Question for This Paper Is: To What Extent Is Burnout a Problem in (International) Education, and What Are Some Solutions?

My motivation for choosing this topic is because of my own background in international education. I wanted to research the levels of well-being of international school teachers, burnout being one of the worst-case scenarios. Besides conducting extensive secondary research, I interviewed a number of international school experts, including a school principal, heads of schools, the director of an international school organization, a psychologist, and an educational coach.

This research paper is interesting for anyone who would like to understand more about burnout in education, the causes, symptoms, trends, effects, and some solutions. This essay may be of particular interest to school boards and leadership teams looking for ways to retain and support educators, increase their levels of engagement, and foster positive school cultures.

The following sub-questions will be covered:

- What is burnout, and what are its causes and symptoms?

- To what extent is burnout an issue in education?

- What are some effects of educator burnout?

- What areas may be addressed to prevent educator burnout and improve their engagement and well-being?

- What do several international school leaders have to say on the topic of well-being and burnout in international schools?

Last, the paper will end with a summary and a discussion of the limitations of the research.

Burned Out Educators: What Is Burnout, What Are Its Causes and Symptoms?

Burnout is defined by WHO as a “syndrome conceptualized as resulting from chronic workplace stress that has not been successfully managed”. Another definition of burnout from experts Maslach and Leiter is “Burnout is a mismatch between the nature of the job and the nature of the person who does the job”. The result is an “erosion of the human soul”. The word erosion refers to the gradual wearing down of a person’s spirit, which is why burnout is so difficult to catch.

WHO’s “chronic stress” and Maslach and Leiter’s job-person “mismatch” can be found in 6 different areas:

- Workload – there is too much work, not enough time, and a lack of resources.

- Control – people are unable to make choices and decisions to solve problems and improve situations.

- Reward – the external reward (pay, benefits, bonuses) may be low, but more importantly, the intrinsic reward of finding value, joy, and meaning in work is no longer present. There also might not be any recognition for the work being done from a management level.

- Community – there is a lack of support and there may be unresolved conflicts causing anxiety, stress, frustration, and bitterness.

- Fairness – where rules apply to some and not others when people are treated differently, where conflict resolution doesn’t allow for feelings of safety and transparency.

- Values – when there is a difference between what an organization says it wants and values, and what it actually promotes and does; when there is a conflict between what is required on the job and a person’s own principles.

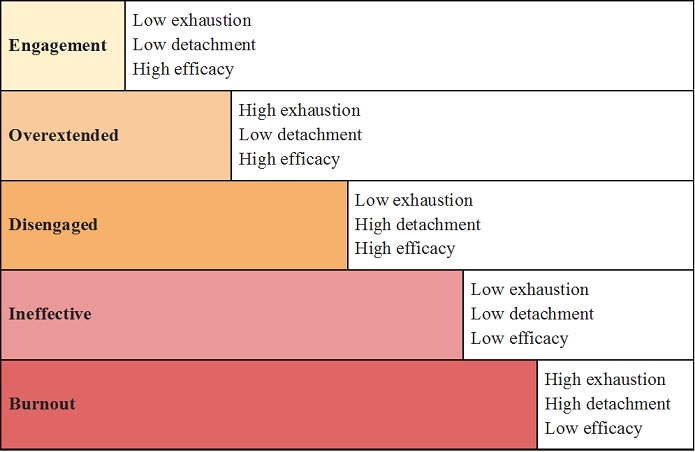

A person suffering from burnout may have one or more of the following symptoms, and therefore burnout can be referred to as a continuum (see Figure 1):

- Feeling exhausted physically and mentally – causing a myriad of stress-related physical and mental problems such as headaches, high blood pressure, a chronic lack of energy, gastrointestinal problems, anxiety, insomnia, low immune system, and depression. People in this state find it very difficult to recover from a day’s work, wake up tired, and never feel rested. Self-care may be lacking, and concentration and focus are difficult. People find themselves feeling hopeless, irritable, worthless, and tense. Coping mechanisms may include behaviors such as overeating or drug and alcohol abuse, causing a cascade of other issues.

- Feeling cynical, negative, and detached towards their job and/or career. A job that used to be meaningful, interesting, and fun now unfulfilling, and causes misery and unhappiness. People start distancing themselves from the job in order to protect themselves emotionally, and they stop involving themselves in order not to feel disappointed.

- Personal inefficacy – being less productive, and efficient and feeling that they are not making a difference. This also may mean that people develop a lack of confidence in themselves and their abilities.

(Burn-out an ‘Occupational Phenomenon’: International Classification of Diseases; Kelly; Maslach and Leiter)

Figure 1 – The Burnout Continuum (Kelly)

Based on several metanalyses, the biggest causes of burnout in education are (Maij):

- Workload

- Classroom size

- Work ambiguity

- Conflicting tasks

- Lack of autonomy and control

- Lack of support

- Emotionally taxing

- Lack of growth opportunities

- Personal factors – not work-related

Another research undertaken by Kelly in international schools identified too heavy a workload, lack of control, and lack of a supportive community as the biggest factors contributing to educator burnout.

To What Extent Is Burnout an Issue in Education?

The educational sector has been hard-hit by COVID. Burnout rates among educators were already high pre-COVID compared to other market sectors; now they are even higher. To illustrate the gravity of the situation I have collected a variety of statistics from the USA and the UK, as these were readily available; statistics from the Netherlands, where I am currently residing; and for international schools, a sector that I have worked in for about twenty years. However, I ran into articles about teacher burnout and high-stress levels in Japan, Hong Kong, China, Spain, Sweden, and Australia, but for simplicity’s sake, I have not included them in this essay.

Statistics for the US in 2019 – still relevant in 2022:

- 44% of K-12 workers say they “always” or “very often” feel burned out at work, compared with 30% of all other workers.

- 52% report burnout.

- 35% of college and university workers report burnout, making educators among the most burned-out groups in the U.S. workforce.

(The Current State of Teacher Burnout in America; Berger; Marken).

2021 statistics for the UK:

- 43% of teachers say they have experienced all components associated with burnout.

- 89% responded that they felt a lack of energy or exhaustion in relation to their job ‘some or all of the time (29% ‘all of the time.’)

- 80% felt negativity or cynicism related to the teaching profession ‘some or all of the time (31% all the time.)

- 73% said that they felt reduced professional efficacy (or ability to perform their job as expected) ‘some or all of the time (14% all the time)

- 59% said that they felt mentally distanced from their job ‘some or all of the time (10% ‘all of the time.)

(Significant Signs of Burnout amongst Teachers)

- 70% reported an increased workload over the last 12 months

- 95% said they were worried about the impact on their wellbeing

(One in three teachers plan to quit, says National Education Union survey).

For The Netherlands, pre-pandemic, the rates of burnout were already at 27.4 % compared to the average 17% in other sectors, with one in six teachers experiencing symptoms of burnout (Sikkers).

It’s difficult to find statistics for international schools, but Dr. Helen Kelly did her own research in 2021 with 275 teachers filling in her 66 question-survey. The results are similar to trends in the national education sectors. Below you can find some examples:

- 80% reported increased work-related stress levels

- 77% said their workload had increased

- 61% reported moments of being close to breaking point

- 70-75% felt exhausted, overwhelmed, and anxious

Even though the exact statistics differ per country, region, type of school, etc. the trends show that, in general, educators are suffering from high rates of burnout and stress, and they are in great need of more support. A meta-analysis from the Universities of York and St John looking at burnout across primary, secondary, and tertiary sectors over the last 35 years, concluded that “This is a global issue, and it is likely that it has only been exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic. Protecting educators from burnout should be central to international policy aimed at reducing teacher turnover” (Teacher Burnout Causing Exodus from the Profession, Study Finds).

What Are Some Effects of Educator Burnout?

Effect on Educators

Burnout often occurs in careers that are focused on servicing people and have high levels of interpersonal interactions. Educators have lots of face-to-face contact – all day – with students, colleagues, administrators, and parents. Even when the interactions are positive, educators can feel emotionally and physically drained at the end of the day. Many interpersonal exchanges also mean that there is a lot of room for potential conflict (Kelly; Maslach and Leiter).

Educators work long hours and are often dedicated professionals who entered education with the desire to make a difference. It is very painful for educators to start experiencing symptoms of burnout, feeling that they no longer invest their heart and soul into the job they once loved. Instead, they grow irritable and cynical and the quality of their teaching deteriorates (Kelly; Maslach and Leiter).

Burnout not only affects an educator’s career (being out on sick leave for longer periods of time, feeling the need to quit the profession and change careers) but also is harmful to their self-esteem, self-confidence, ability to cope, lifestyle, hobbies, relationships and home situation (Kelly; Leiter and Maslach).

Educators Leaving the Profession and Increases in Educator Shortages

Besides the detrimental effects on the individual, another effect of burnout is that teachers who experience burnout are more likely to leave the profession, contributing to the increasing shortage of educators worldwide (Teacher Burnout Causing Exodus from the Profession, Study Finds).

To illustrate the increasing teacher shortages, in the US, as of March 2022, 44% of public schools currently have teaching vacancies and this number may increase as over half of U.S. teachers are reported contemplating quitting (Berger).

For the UK, the National Education Survey reported that “one in three teachers plan to quit the classroom within five years … causing a shortfall of 30,000 classroom teachers, particularly at the secondary level, where 20 % of teacher training vacancies are unfilled” (One in three teachers plan to quit, says National Education Union survey). Another UK study mentioned that vacancies for secondary school educators increased by 47 % last year and 14 % in 2019, before COVID (Yeomans).

In The Netherlands, 64% of 2018/2019 primary teacher vacancies were difficult to fill, and 10% to this day remain unfulfilled amounting to a total of 9100 full-time jobs (Feiten en cijfers over het lerarentekort; Poortvliet).

At international schools, in Dr. Kelly’s survey, 31% have considered leaving the teaching profession because of the pandemic.

Decreases in Student Performance and Wellbeing

Ultimately, the lack of educators and their increased stress levels have a negative effect on the core business of schools: offering quality education to students. Teachers who experience symptoms of burnout are less effective in their job. Given the fact that mental health issues are on the rise for students all around the globe (University of Calgary), students need good teachers now more than ever.

A large body of research supports the importance of teacher-student relationships in increasing levels of student motivation and improving student behavior, attendance, performance, and social skills. Good relationships also benefit educators as they experience more joy in the classroom instead of anxiety and stress (Sparks).

For example, a UK study found:

- “During one year with a very effective Maths teacher pupils gain 40% more in their learning than they would with a poorly performing maths teacher.

- The effects of high-quality teaching are especially significant for pupils from disadvantaged backgrounds. Over a school year, these pupils gain 1.5 years’ worth of learning with highly effective teachers compared with 0.5 years with poorly performing teachers.” (O’Leary, Parliament, and Policy: April and June 2015).

Supporting educators and ensuring their well-being needs are met will increase the chances of them staying in the profession and being more effective in their job. The knock-on effect is that students will be happier and more engaged and more successful in their learning (Morrison).

Financial Costs

Last, there are financial costs associated with burnout – exact figures are difficult to come by, however, for the US, estimates of burnout in education run into $2.2 billion a year. An article from UK-based TES Magazine from April 2022 describes how schools not only have seen increases in budgets for supply teachers of 400%, but now also the higher costs of living, energy, and inflation will bring some schools into the financial crisis with their only option to cut more staff and/or not replace the ones who are leaving (Mason). In the Netherlands, sick leave is costing the education sector as a whole €275 million (Het Onderwijs Brandt Mensen Op). There are no figures available for international schools regarding costs.

Given that burnout comes with high costs for the individual, the students, and schools, that it occurs relatively frequently, and that recovering from burnout is a difficult, arduous, and time-consuming process, it makes sense to focus on the prevention of burnout instead of crisis management.

What Areas May Be Addressed to Prevent Educator Burnout and Improve Their Engagement and Wellbeing?

Burnout isn’t always taken seriously and is seen primarily as a problem of the individual and not a school’s responsibility. Even though schools might offer workshops, coaching, or counseling around stress management (which is helpful for the individual) the greater organizational issues causing the burnout, aren’t addressed. Kelly, Maslach, and Leiter identify organizations – schools in this case – as key to both causing and preventing burnout. Therefore, prevention has to happen on two levels: the organizational and the individual.

For schools this would mean creating a positive school culture and promoting teacher engagement by offering things like realistic workloads, smaller class sizes, opportunities for professional development and growth, transparent conflict resolution procedures, a supportive and caring administration, and community, matching the school’s values with daily practice and procedures, recognizing teachers and celebrating success, offering fair pay, and allowing teachers to have a say.

For educators, preventing burnout means maintaining high levels of energy, motivation, and self-efficacy throughout their teaching careers. This means finding ways to unwind, recover and disengage psychologically from work, engaging in hobbies and fun activities during weekends, holidays, and time off, learning how to manage anxiety and stress levels, taking short breaks during the day, and analyzing the work environment to see where they can exert control and make changes that improve their work. For the latter, herein lies an opportunity to make larger improvements, benefiting the school as a whole.

However, if burnout has already occurred, the goal for the individual could be either of the following:

- Immediate solutions and a gradual return to work with ways to unwind and recover, manage stress levels, and find solutions regarding the six causes of burnout.

- If finding solutions in the work environment is proving to be challenging and/or the mismatch remains too great, the coaching goal might be quitting education and finding another career.

Prevention requires long-term strategies, investments, commitment, and patience. It is an ongoing process that needs attention at the individual and organizational levels.

What Do Several International School Leaders and Experts Have to Say on the Topic of well-being and Burnout in International Schools?

Because I initially wanted to know more about burnout and well-being in international education, and statistics were hard to come by, I decided to interview several experts in the field. I conducted the qualitative interviews online or face-to-face. I interviewed one principal, two heads of schools, one director of an international educational organization, a freelance educational coach, a psychologist, and an expert in burnout in international education (Dr. Helen Kelly).

For most of the experts interviewed – except for the coach – educator wellbeing and burnout was not a topic that appeared urgent or in much need of attention. It was difficult for interviewees to comment on this objectively, as none had hard facts, and could only speak from their experience.

To phrase one of the heads of the school: “The burn-out pandemic in schools is very much a Dutch/European thing. In all my years in international schools, I have not come across burn-out to the level it is at in the Netherlands”. What she meant with this statement is that labor laws in non-European countries do not account for long periods of sick leave, leaving teachers no option, they have to continue working. I thought this was a very interesting observation, which probably holds some truth to it. Another interpretation is that burnout does exist, but that international educators with burnout symptoms quit their job and move on, so burnout remains undiagnosed, unrecorded, and hidden. However, she may be right that the rates of burnout in international education are smaller and not only because of the lack of protective labor laws.

Other reasons for lower burnout rates are that the rewards (a lack of rewards is one of the causes for burnout) in international education might be higher than in public schools in the USA, UK, and The Netherlands. Salaries, benefits, and in some cases low costs of living make international school teaching financially attractive. Other rewards, such as travel, adventure, and living and working in international communities, attract educators as well. Several of the people I interviewed mentioned that COVID influenced this latter reward negatively for international school educators, and may have influenced a number of educators to repatriate after two years of COVID.

A protective factor against burnout is supportive leadership and community. Discussion of the leadership factor first, the heads of school and principal invested in building positive relationships with their staff, which highlights how important supportive leadership is in preventing burnout. Especially during COVID, they went out of their way to personally check with staff to see how they were doing. I also asked them questions about their own self-care. In these cases, the heads of schools and principals I interviewed had personalities that allowed them to deal well with stress. They were good at disengaging from work even though they worked very hard, and approached their daily tasks with confidence and light-heartedness. Regarding supportive communities, generally speaking, international school communities, though transient, are tight-night, highly social, and accessible. In addition, many schools have elaborate transition and welcoming programs for their new staff and social committees that organize fun social events throughout the year. These types of community-building programs may be less present at public schools in the UK, the US, and The Netherlands.

Last, one of the primary factors for burnout is heavy workloads. However, even though workloads at international schools can be high, in many non-Western countries, a lot of household duties are taken care of by help, giving teachers time to work hard and play hard, allowing them to relax, unwind and recover from their job.

Burned Out Educators: Effect on Students and Schools

Summary

Burnout and increased stressed levels in education are trends that are here to stay. Governments and schools are currently not addressing the matter effectively and as a result, there are teacher shortages around the world. Symptoms of burnout are physical and mental exhaustion, cynicism towards work, and feelings of personal inefficacy. For individual educators who get burned out, the effects can be severe both professionally and personally, and recovery can be long and challenging. The effect on students and schools is that the quality of education decreases.

It does appear that burnout levels at international schools may be less than at public schools in the US, UK, and The Netherlands for a number of reasons, including lack of supportive labor laws in non-Western countries, but also protective factors such as well as financial and intrinsic rewards and welcoming and supportive communities. Even though my interviews seemed to indicate this, the data is insufficient to come to any hard conclusions – more on this in the next section. However, even if one can suppose that burnout is less prevalent among international educators, it is still an issue that COVID has exacerbated and some educators are definitely showing symptoms of burnout according to Dr. Kelly’s research.

Prevention of burnout is essential. One of the solutions is doing work environment audits in the areas of workload, rewards, community, fairness, and values. Schools should focus on increasing teacher engagement and creating a positive school culture. To prevent burnout at the individual level, educators need to create moments to unwind and distance themselves from their work on a daily basis and manage their stress levels. If there are mismatches between the work and the person, coaching and counseling can help with finding ways to bridge these areas, or in the worst case scenario, help an individual change career.

Limitations and Further Research

One of my main sources regarding burnout theory was Maslach and Leiter’s 1997 book The Truth about Burnout: How Organizations Cause Personal Stress and What to Do about It. A limitation is that it is a relatively old source, however, Maslach and Letier’s description of burnout is still being used by many people today. Maslach persists as one of the main experts in the field and she has continued building on her original research from 1997.

Initially, I had wanted to focus on burnout in international schools only, but it was very difficult to find information on this topic – and therefore I extended my secondary statistical research to include public schools in a few Western countries. This in itself is a limitation, and it would be interesting to conduct a much larger scale research to find out about burnout in education in a wide variety of countries and cultures.

The main resource I used for international schools was Dr. Helen Kelly’s research that she conducted in 2021 with 275 teachers filling in her 66 question-survey. The limitation of her findings is that COVID was prevalent and influencing all facets of life, causing burnout and increased stress levels for many educators. The question remains, what were the levels of burnout prior to COVID at international schools? I was unable to find an answer to this question. The fact that educator burnout and well-being didn’t appear to be a critical topic for international school experts can mean two things. Firstly, burnout is present but isn’t recognized due to the transient nature of international schools, the lack of protective labor laws in many countries around the world, and/or the experts I interviewed are simply unaware. Another possibility is that burnout is not as prevalent in international schools as it is in public schools in the USA, UK, and The Netherlands because the sector has more protective factors against burnout. My primary qualitative research was also limited in number and its value is more of a reconnaissance than that any of the data can be used to identify significant trends. In any case, the inconclusiveness of the question regarding burnout in international schools requires much further quantitative and qualitative research.

References

Arvidsson, I., Leo, U., Larsson, A. et al. Burnout Among School Teachers: Quantitative and Qualitative Results From a Follow-up Study in Southern Sweden. BMC Public Health 19, 655 (2019).

Bauerlein, Valerie, and Yoree Koh. “Teacher Shortage Compounds COVID-19 Crisis in Schools.” the Wall Street Journal, Dow Jones & Company, 26 Dec. 2020.

Berger, Chloe. “Teachers Are the Most Burned Out Workers in America.” Fortune, Fortune, 15 June 2022.

“Burned Out: Why Are So Many Teachers Quitting or off Sick With Stress?” the Guardian, Guardian News, and Media, 13 May 2018.

“Burn-Out an ‘Occupational Phenomenon’: International Classification of Diseases.” World Health Organization, World Health Organization, 28 May 2019.

Callum, Mason. “Schools Are on the Financial Brink - And It’s Going to Get Worse.” Tes Magazine, 1 Apr. 2022.

“Feiten en Cijfers Over Het Lerarentekort.” Arbeidsmarktplatform Po, 24 Feb. 2022.

“Het Onderwijs Brandt Mensen Op.” Intermediar, 30 Sept. 2015.

Holley, Karin. “Interview With Deidre Fischer, Consultant, Coach, Trainer at DF Education”. 22 July 2022.

Holley, Karin. “Interview With Douglas Ota, Child Psychologist and Founder of Safe Passage.” 29 August 2022.

Holley, Karin. “Interview With Helen Stanton, Head of School at Florence Bilingual School”. 11 June 2022.

Holley, Karin. “Interview With Jane Larsson, Executive Director at Council of International Schools (Cis).” 30 June 2022.

Holley, Karin. “Interview With Juliëtte Van Eerden, Head of School at Rak Academy”. 17 June 2022

Holley, Karin. “Interview With Justin Walsh, Principal at American International School Riyadh.” 30 June 2022.

Johnson, S., Cooper, C., Cartwright, S., Donald, I., Taylor, P. And Millet, C. (2005), “The Experience of Work‐Related Stress Across Occupations”, Journal of Managerial Psychology, Vol. 20 No. 2, Pp. 178-187.

Kelly, Helen. “The Myth of the Resiliant Educator.” Wellbeing in International Schools Magazine, Mar. 2022, Pp. 10–11.

Maij, David L.R. Stress en Burn-Outklachten in Het Onderwijs – De Cijfers, Oorzaken en Een Stappenplan Voor Verbeterde Vitaliteit. LINKEDIN, 24 Sept. 2021.

Maslach, Christina, and Michael P. Leiter. The Truth About Burnout: How Organizations Cause Personal Stress and What to Do About It. Jossey-Bass, a Wiley Imprint, 1997.

Maslach Christina and Michael P. Leiter. Understanding the Burnout Experience: Recent Research and Its Implications for Psychiatry. World Psychiatry. 2016 Jun;15(2):103-11. Doi: 10.1002/Wps.20311. Pmid: 27265691; Pmcid: PMC4911781.

Marken, Stephanie, and Sangeeta Agrawal. “K-12 Workers Have Highest Burnout Rate in U.S.” Gallup.com, Gallup, 8 June 2022.

Morrison, Nick. “Stopping the Great Teacher Resignation Will Be Education’s Big Challenge for 2022.” Forbes, Forbes Magazine, 21 Apr. 2022.

“One in Three Teachers Plan to Quit, Says National Education Union Survey.” the Guardian, Guardian News, and Media, 8 Apr. 2021.

O’Leary, Tim. “Classroom Vibe: Making Culture Your Superpower With Dr. Tim O’Leary, PH.D.” Education Perfect. Epic 2022, 15 June 2022, Online Webinar.

Park, Eun-Young, and Mikyung Shin. “A Meta-Analysis of Special Education Teachers’ Burnout.” Sage Open, Apr. 2020, Doi:10.1177/2158244020918297.

“Parliament and Policy: April and June 2015.” Sutton Trust, 12 June 2015.

Poortvliet, Joelle. “Geen Regio Meer Zonder Lerarentekort.” de Algemene Onderwijsbond, 11 Feb. 2022.

Scott, C., Stone, B., & Dinham, S. (2001). I Love Teaching But.. International Patterns of Teacher Discontent. Education Policy Analysis Archives.

“Significant Signs of Burnout Amongst Teachers.” Education Support, Supporting Teachers and Education Staff, 29 Apr. 2021.

Sikkers, Robert. “Weer Meer Burn-Outklachten in Het Onderwijs.” Algemene Onderwijsbond, 3 Sept. 2020.

Sparks, Sarah D. “Why Teacher-Student Relationships Matter.” Education Week, Education Week, 17 Sept. 2021.

“Teacher Burnout Causing Exodus From the Profession, Study Finds.” The University of York, 21 July 2021.

“The Current State of Teacher Burnout in America.” American University - School of Education, 10 Mar. 2019

The University of Calgary. “Youth, the Pandemic and a Global Mental Health Crisis: Depression and Anxiety Symptoms Have Doubled, Help Needed, Warn Clinical Psychologists.” Sciencedaily. ScienceDaily, 9 August 2021.

Yeomans, Emma. “Fears Grow Over Supply of Qualified Teachers.” News | the Times, the Times, 19 June 2022

Interviews

[1] I Used Educators and Teachers Interchangeably, Referring to Anyone Working In Primary and Secondary Schools.