A Research Paper By Julia Paulsson Jandl, Relationship Coach, AUSTRIA

What Motivates People to Implement Behaviour Change?

Clients seeking out coaching typically aspire to achieve personal or professional goals, overcome challenges or seek support to get ‘unstuck’. They desire some form of change, movement or growth. It is the role of the coach to partner with the client in a thought-provoking and creative process that inspires clients to maximize their personal and/ or professional potential (ICF, 2021) to support the client in achieving this change or in getting them closer to achieving the desired goals than they have ever been before. However, we all know that behavioural change is hard. How many of us have made and broken New Year’s resolutions or let that gym membership lie idle? So, how do clients move towards and maintain change? And how can coaches utilize insights into behaviour and behavioural change processes in their practice?

Behaviour Change

What Influences Behaviour?

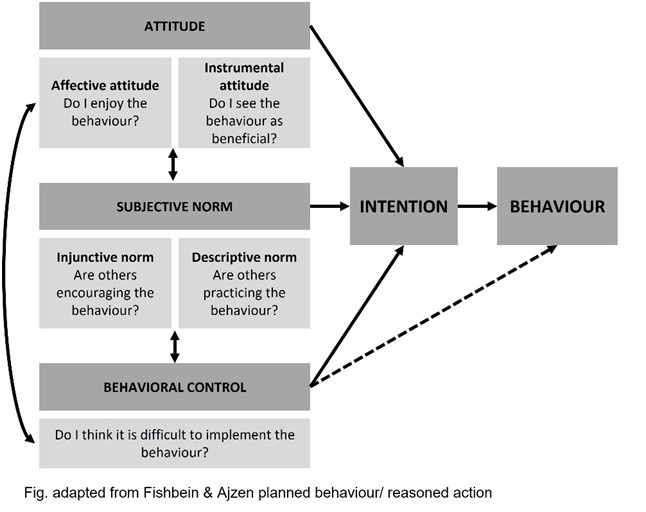

One theory looking at behaviour and behaviour change is the theory of planned behaviour/reasoned action developed by Fishbein and Ajzen in the 1970s. The theory posits that intention to execute an action is influenced by a person’s attitude towards the behaviour, perceived subjective norms associated with the behaviour and behavioural control (Madden, Ellen & Ajzen, 1992). The intention functions as a mediator between these variables and behaviour and are of critical importance in predicting behaviour (Ajzen, 1991). A person is more likely to execute an action if they feel positive about the behaviour and believe in its benefit; if they believe the behaviour is socially encouraged and if they see others around them engage in the behaviour; and if they have strong confidence in their ability to engage in the behaviour. These factors combined, influence the degree of the person’s intention and help predict behaviour. Behavioural control is shown in the graph as influencing intention, but also as having the ability to directly impact behaviour. This is because even if the intention is strong, barriers may be too significant to translate intention into action. For instance, a person might be ready to go out on a date after a breakup, approach meeting new people with curiosity and sees it as beneficial for their overall well-being. They may have a supportive family and peer environment encouraging them to go out and the date and may even have friends who are also active in the dating pool and may also be active on apps and get positive responses there. All factors may positively impact their intention of actively going out on a date. However, due to a sudden illness, they need to go to a hospital and despite strong intentions are ultimately not able to go on a date at that moment. So irrespective of the degree of intention, the barrier controlled the behaviour. Also, it is important to note, that intention does not necessarily directly translate into behaviour. Webb and Sheeran (2006) conducted a meta-analysis of 47 experimental tests of intention-behaviour relations and found that a medium-to-large change in intention, leads to a small-to-medium change in behaviour, known as the intention-behaviour gap. Insights into behavioural theories can be practically applied to develop interventions.

Stages of Change

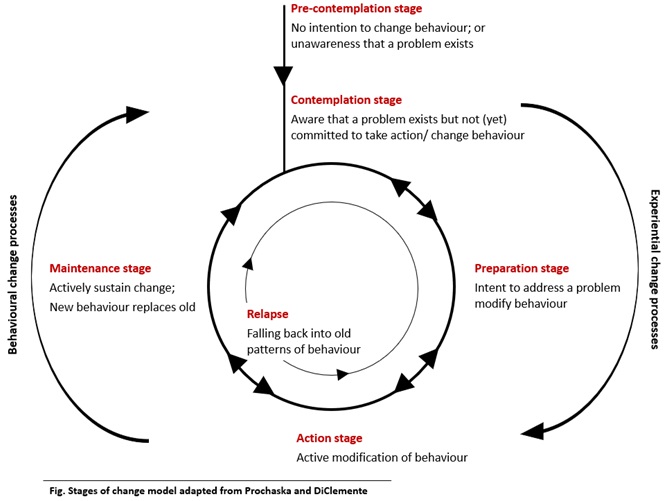

One such practical application is the Transtheoretical Model (TTM) or Stages of Change Model, developed by Prochaska and DiClemente in the 1970s. The model posits that individuals go through six stages of behavioural change i) pre-contemplation, ii) contemplation, iii) preparation, iv) action, v) maintenance and vi) relapse (Prochaska & DiClemente, 1982).

At the pre-contemplation stage, clients have no intention of changing their behaviour or may be unaware that an issue exists. At the contemplation stage, the client is aware of the issue, however, has not (yet) committed to implementing changes. At the preparation stage, the client has decided to take action to address the issue at hand, which typically requires that the client is convinced that change is positive and believes in their ability to change. At the action stage, the client is taking action to modify the behaviour. At the maintenance stage, new behaviour replaces old behaviour. Relapse may occur particularly at the action and maintenance stage and involves a failing back to old patterns of behaviour. Change is complex and these stages are hence not to be seen as strictly linear. They can be rather cyclical with progression and regression between stages and different amounts of time spent at the different stages. The TTM seeks to meet clients where they are in their change processes. Coaches can utilize this insight by assessing which phase clients are in with regard to the change they desire and emphasising different processes of change depending on the stage.

Processes of Change Supporting Movement Through Stages of Change

Prochaska and DiClemente identified ten processes of change (Prochaska & DiClemente, 1982), which are covert and overt activities that individuals use to modify behaviour and which can be grouped into experiential processes of change and behavioural processes of change.

| Ten Processes of Change | Experiential Processes of Change |

|

Consciousness-raising |

Efforts to seek new information and gain a deeper understanding of oneself (the who) and the issue (the what) |

|

Dramatic relief |

Experiencing and expressing feelings about the issue and potential solutions |

|

Environmental re-evaluation |

Evaluating how the problem affects the physical and social environment |

|

Self re-evaluation |

Affective and cognitive re-assessment of how one feels and thinks with regard to the issue |

|

Social liberation |

Increasing awareness about acceptable, problem-free behaviours/lifestyles available in the society |

|

Counterconditioning |

Substituting alternatives for the problem behaviour |

|

Helping relationships |

Trusting and utilizing the support of someone who cares |

|

Reinforcement management |

Rewarding oneself or being rewarded by others for making changes |

|

Self-liberation |

Choosing and committing to act/ belief in own capacity to change |

|

Stimulus control |

Avoiding or countering stimuli that elicit problem behaviour |

Prochaska and DiClemente (1983)went on to analyse the relative importance of these ten change processes at the different stages of change. Overall, experiential processes, seem particularly relevant in the early stages of change. i.e contemplation and preparation stage. Behavioural processes are used more in later stages of change i.e action and maintenance stages.

Individuals at the precontemplation stage use the change process less frequently than individuals at any other stage of change. They may become defensive when faced with pressure to change. At the contemplation stage, individuals are becoming more aware of how they think and feel about the problem behaviour and the consequences of the problem behaviour. They are more open to new information and insights and weigh the pros and cons of changing. At the preparation stage, clients have committed to change and perceive the positives in favour of the change to outweigh the negatives. They start planning for change and identify alternative behaviours as well as resources that can help them and strengthen their self-efficacy. At the action stage, clients take proactive steps in changing their behaviour. They may be more open to receiving the support of caring for others, introducing new behaviours to substitute the problem behaviour, and avoiding stimuli that may increase the risk for the problem behaviour to re-emerge. At the action stage, clients benefit in particular from self-reinforcements and reinforcements by others to remain motivated. The maintenance stage sees similar change processes to the action stage, with counter-conditioning and stimuli control continuing to remain particularly relevant. This seems to reinforce that the maintenance stage is an active phase, not a passive state. Relapse, or the return to problem behaviour, can occur at any stage. Relapsers increasingly utilized both experiential as well as behavioural processes (Prohaska& DiClemente, 1983). This may indicate that relapsers learn from going through the stages of change and can draw on their learning.

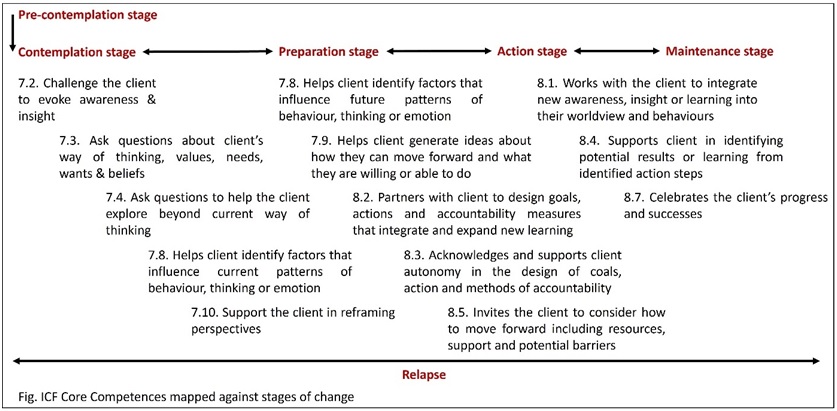

How May Insight Into Processes of Change Link to the International Coaching Federation’s Core Competencies?

The ICF, published updated ICF Core Competences, following 24 months of extensive research (ICF, 2019). The ICF Core Competencies support a greater understanding of the skills and approaches used within today’s coaching profession and include eight core competencies organized in four domains based on commonalities and interdependencies between competencies within each domain (ICF, 2019b). The framework outlines critical skills for coaches when it comes to the foundation of coaching; co-creating a coaching relationship; effective communication; and cultivating learning and growth. While all core competencies are critical throughout the coaching process and the coaching relationship and need to be present in all coaching sessions, some competencies may be particularly effective depending on the stage of change the client is in.

Evoking awareness is the 7th core competence and is defined as facilitating client insight and learning by using tools and techniques such as powerful questioning, silence, metaphor or analogy. Skills under this competence are more experiential in nature and may be particularly impactful in supporting clients in the earlier stages of the change process.

Facilitating client growth is the 8th core competence and is defined as partnering with the client to transform learning and insight into action while promoting client autonomy in the coaching process. Many of the skills under this competency focus on facilitating behavioural change processes and may be particularly effective in facilitating movement through later stages of change. The explicit reference to fostering client autonomy may support the self-efficacy of clients.

The Impact Of Behaviour Change

Behavioural change is impacted by myriad factors, including attitudes and beliefs, social norms and clients’ perceptions of resources available to them and barriers to overcome. Different clients may be influenced by these factors in very different ways and interventions will need to be tailored to the individual client and their context to be most effective. Understanding theories and models of change can be a valuable step to enable coaches to identify which stage their clients are at with regards to the desired change and in tailoring the interventions and emphasizing corresponding core competencies accordingly.

References

International Coaching Federation (ICF) (2021) ‘ICF Code of Ethics’. (Accessed: 21 October 2022)

Madden, T.J., Ellen, P.S., & Ajzen, I. (1992). A comparison of the theory of planned behaviour and the theory of reasoned action. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 18(1), 3-9. (Accessed: 28 October 2022)

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behaviour. Organizational Behaviour and Human Decision Processes 50(2), 179-211. (Accessed: 28 October 2022)

Webb, T. L., & Sheeran, P. (2006). Does changing behavioural intentions engender behaviour change? A meta-analysis of the experimental evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 132(2), 249–268. (Accessed: 28 October 2022)

Prochaska, J.O. &DiClemente (1982). Transtheoretical therapy: toward a more integrative model of change. Psychotherapy: Theory Research and Practice, 19, 276-288. (Accessed: 21 October 2022)

Prochaska, J. O., & DiClemente, C. C. (1983). Stages and processes of self-change of smoking: Toward an integrative model of change. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 51(3), 390–395. (Accessed: 21 October 2022)

International Coaching Federation (ICF) (2019a) ‘Updated ICF Core Competencies. (Accessed: 28 October 2022)

International Coaching Federation (ICF) (2019b). ICF Core Competencies. (Accessed: 21 October 2022)

Lipschitz J., Yusufov M, Paiva A and others, Transtheoretical Principles and Processes for Adapting Physical Activity: A longitudinal 24-month Comparison of Maintainers, Relapsers and Nonchangers, Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology2015, 37, 592-606