Research Paper By Ashley Gork

(Career Coach, UNITED STATES)

There are many differences between Steve Jobs and Steve Smith. For example, you’ve most likely heard of Steve Jobs, known for being the cofounder and former CEO of Apple Inc. And you might be asking yourself, who is this Steve Smith? While both men studied technology innovation and both dropped out of college after six months, one huge difference marks the difference between them: Ambition.

Psychologist Dean Simonton, who studies genius, creativity and eccentricity at the University of California, Davis, has defined ambition as a combination of energy, determination and goals. “People with goals but no energy are the ones who wind up sitting on the couch saying ‘One day I’m going to build a better mousetrap.’ People with energy but no goals just dissipate themselves in one desultory project after the next,” he said to TIME Magazine. This means that while the concept of ambition can be viewed as an evolutionary product, changing with the definitions of social status, it can also be seen as a fixed combination of two innate qualities: determination and energy.

Humans, like other species, have varying levels of ambition. Studies on brain functionality have shown that people with more activity in their limbic systems tend to score higher in scales measuring persistence. Likewise, research has suggested that energy levels might be correlated with genetics, indicating that a significant aspect of ambition is hereditary. However, determination and energy can be also developed via coaching. Those who utilize the skills of a coach to deepen their motivations can harness a stronger attachment to their ambitions and become more likely to achieve their goals. “A lot of times it’s just finding the right thing to be ambitious about,” Simonton affirmed.

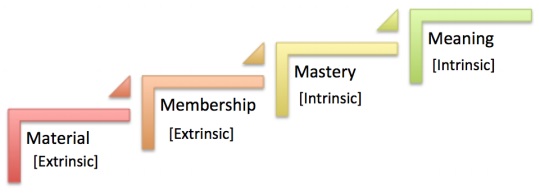

The purpose of this paper is to explore The Hierarchy of Autonomous 1 Motivations2 and to learn how each level represents a different probability and satisfaction rate derived from achieving one’s goals. It exists in parallel with Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, but focuses specifically on what motivates humans to reach new levels of self-defined achievement within their professional and personal lives. The theory works within a broad paradigm shift from extrinsic to intrinsic motivators and moves within the following four levels of increasing complexity and significance: material, membership, mastery and meaning. As goal-setters move through these levels, adopting deeper attachments to their motivations, they are more likely to remain committed to their goals and to experience satisfaction from achieving them.

“Autonomous” is defined as self-determining and represents goals that are conceptualized and developed by the person wishing to achieve them. Goals that come from achievements one ought to have or should have will not be explored within the context of this paper. 2 “Motivation” is defined as a psychological desire or willingness to reach one’s goals. Biological motivations, such as the need to eat, sleep or perpetuate the human species, will be ignored for the purpose of this paper.

Material Motivations

At the most basic psychological level, humans can be motivated by material gains. Money used to upgrade laptops, purchase vacation homes or buy expensive steak dinners fit into this low-level category. These funds and other material gains can be viewed as extrinsic motivators, bringing about validation from outside sources. In other words, they encourage goal-setters to reach outside of themselves to find satisfaction.

Human motivation psychologist Edward Deci researched the effectiveness of using money as a motivator by incentivizing students to solve puzzles. Deci found that those who were offered money to find the correct solution were less interested in working on the task than students who were not materially motivated. Moreover, those who were not incentivized by money worked longer and with more interest on the task. Deci’s work showed the weaknesses associated with extrinsic motivation, finding that those who were intrinsically motivated had higher levels of persistence and interest in the project. “We need to compensate people fairly, but when we try to use money to motivate them to do tasks, it can very likely backfire on us,” he said.

Similarly, Rosabeth Moss Kanter, a professor at Harvard Business School and author of Evolve, studied the use of money as an incentive for high-innovation companies. Her research found that money did not encourage people to get excited about their daily tasks nor did it help them to feel fulfilled. “Money can even be an irritant if compensation is not adequate or fair, and compensation runs out of steam quickly as a source of sustained performance,” she wrote for Harvard Business Review. Kanter added that people who are happy at work are often those who find that they can make positive impacts on social needs. This does not directly involve material gains, she noted.

Membership Motivations

The next level of motivation involves the ability for one to become a member within a group. Also an extrinsic motivation, this desire for connectedness stems from biological roots, but has also shown to have psychological benefits. For example, research has found that those who feel connected to others tend to adopt the goals of those around them. Psychologists Gregory Walton, Geoffrey Cohen, David Cwir and Steven Spencer released a research paper in the March 2012 issue of the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology that found college students who shared a birthday with an author of an article worked longer on an impossible geometry problem than participants who did not share the same birthday. Additionally, those who shared the birthday had a more positive outlook about math in general. This indicates that even a small arbitrary relationship between people can increase motivation.

A collection of five experiments created by psychologists Priyanka B. Carr and Gregory Walton of Stanford University also emphasized the importance of membership as a motivator. The results from one of the studies found that those who felt they were tackling a puzzle as a team ended up working on the challenge for 48 percent longer of a time than those working in the control group. This was even true when the team members were physically apart. Moreover, those who felt that they were part of a team rated the challenge as more interesting and were found to be less tired from working on it than the other group.

“Working with others affords enormous social and personal benefits,” Walton said, adding that this sense of teamwork “can have striking effects on motivation.” He also noted that the results did not indicate a sense of obligation, competition or pressure to work with others. Thus, motivations driven by membership have proven to be stronger than those that are attached to material gains because they emphasize the additional benefits of social bonds and a sense of belonging.

Mastery Motivations

Those who are motivated by the idea of mastering a task or skill have a stronger connection to the project than those who are motivated by money or membership. One possible reason for this is because mastery often comes in the form of an internal motivation and is driven by one’s own desire and willingness to do something. As people grow and develop, they are constantly learning new information, skills and abilities. This, in larger part, is due to an innate desire to succeed and excel.

Daniel Pink, author of Drive: The Surprising Truth of What Motivates Us, drew upon four decades of scientific research about human motivation to conclude that the carrot-and-stick approach of external rewards is not the best way to motivate people to complete tasks. Instead, Pink argued that humans are motivated by a desire to learn and create new things, among other intrinsic stimuli. “This is why people play musical instruments on the weekend,” he explained, noting that there are often no concrete gains to learning a new skill. In other words, even though mastering a skill has the possibility of bringing about more money or new social circles, the concept in itself can be a true, long-lasting motivator.

Similarly, researchers from San Francisco State University found that people who work hard at improving a skill or an ability experience greater happiness on a daily basis and in the longer term. While mastery has been found to be linked with stress and decreased happiness in the moment, participants of the study reported feeling happier and more satisfied after improving a skill when they looked back on the day as a whole. This indicates that becoming proficient at something is ultimately correlated with emotional benefits.

“No pain, no gain is the rule when it comes to gaining happiness from increasing our competence at something,” explained researcher Ryan Howell. “People often give up their goals because they are stressful, but we found that there is benefit at the end of the day from learning to do something well. And what’s striking is that you don’t have to reach your goal to see the benefits to your happiness and well-being.”

Meaning Motivations

The highest level within The Hierarchy of Autonomous Motivations is the construct of meaning. In other words, those who can derive a sense of purpose from their tasks are most likely to stay motivated and obtain satisfaction from achieving their goals. According to a survey from Deloitte, 73 percent of employees who say they want to work for a “purpose-driven” company have proven that they are engaged in their work. This figure is compared to the 23 percent of employees who say they don’t care about obtaining purpose from their careers despite still being engaged at work.

“People can be inspired to meet stretch goals and tackle impossible challenges if they care about the outcome,” Kanter wrote, citing several social entrepreneurs as examples. Those who work on seemingly impossible tasks, such as solving homelessness or world hunger, are often driven by having a sense of purpose and are thus more dedicated to their goals, she said.

Pink agreed that seeking meaning from a task is the most powerful motivator for achieving one’s goals. He noted that when the profit motive becomes unmoored from the purpose motive, negative effects often occur, including unethical decisions, poor services and subpar products. Conversely, those who find purpose in their jobs tend to be more motived to excel at work, he explained. As an example, Pink cited a quote from Steve Jobs that read: “I want to put a ding in the universe.” He then asserted that the meaning behind the statement is the exact “kind of thing that might get you up in the morning, racing to go to work.”

Coaching application

By understanding and utilizing the Hierarchy of Autonomous Motivations, a skilled coach can help his clients gain awareness about the motivations behind their goals. If a coach recognizes that a client is motived by a low-level commitment to a goal, he has the opportunity to reframe her perspective and encourage her commitment to a stronger motivator. This theory can also be used to explore possible reasons why a client avoids or is unable to commit to a goal. If the coach discovers that his client is attached to a low-level motivator, he can allow her to have the opportunity to reconsider the importance that has been placed on the goal.

To illustrate the varying degrees of autonomous motivations, the paper will now examine the case studies of a client striving to achieve a new goal. Alison, an account executive at an advertising firm, is looking to get promoted to a senior position by the year’s end. At the time of her first coaching session, Alison said her motivation is to make more money and have more authority at the company. The case study will work to display how the various levels within the Hierarchy of Autonomous Motivations can offer a range of probabilities for committing to and achieving goals as well as varying levels of satisfaction attained from the achievements.

Case study

After working hard to get a raise for the past six months, Alison came to her coach distraught and upset. She heard that another employee, one whom she believed was less competent than herself, got a raise at his annual review while she just got a pat on the back at hers. From pervious coaching conversations, her coach knew that Alison enjoyed her job, but that she never stayed late with some of her colleagues as she was often anxious to get home to her family. Alison, aware of this, said she didn’t know why she didn’t put in the extra effort when she knew she wanted the extra money.

Alison’s coach thought it would be a good idea to explore what the raise represented to her client. Initially, Alison said she would just like to have the extra cash flow, but after more exploration, she realized that what she really wanted was to be able to take her twins to Disney World for their birthdays. More questioning revealed that Alison would also like to eventually have enough money to take some time off from work and to contribute her creative talents to her friend’s home décor business.

By asking powerful questions about her client’s motivations, Alison’s coach recognized that the material benefits gained from a potential raise represented much more to her than money. Her coach realized that a trip to Disney World was an opportunity for Alison to bond with her busy kids. By focusing on this potential for a membership opportunity, Alison might develop in a deeper level of motivation for achieving her goal, the coach reasoned.

Alison focused on her goal of going to Disney World with her kids to power through the next several months. Her direct supervisor took notice of her hard work and asked her to head an important project. Alison was ecstatic! She worked hard day and night to excel at this project. Her coach also noticed that Alison’s conversations switched from wanting to make enough money to take her kids on a trip to learning and utilizing new skills. Knowingly, her coach encouraged Alison to revel in this new excitement and to master the new skills. Several months later, Alison got the raise she wanted. She took her kids to Disney World and was even excited to get back to work.

However after several months, Alison began to slip back into her old patterns of wanting to leave early to spend time with her kids. Despite knowing and enjoying the new skills she had learned, she once again began to feel unsatisfied at work. Her coach recalled Alison’s previous mentioning of her friend’s home décor business and asked about that. Alison said she always had a passion for design and felt that if she had the chance to study it in school, she would have been an interior designer. Alison’s coach could hear her voice change when she spoke about design and instinctually knew that this was a real passion for her.

After a few more sessions together, Alison decided that while she enjoyed her work, she could not derive meaning from it. Moreover, she knew that this sense of purpose belonged with her true passion for interior design. She began to work with her coach on a way to transition from the advertising agency to a supporting role in her friend’s business. By harnessing Alison’s connection to meaningfulness, her coach knew that he could help Alison commit to her goal and derive plenty of satisfaction from it.

Conclusion

This paper explained how humans have varying levels of ambition depending largely on the energy and determination they put towards a goal. The Hierarchy of Autonomous Motivations furthered this concept by displaying varying levels of attachment to goals, with each motivator increasing a person’s likelihood of achieving, sustaining and obtaining pleasure from meeting those goals.

Coaches who use The Hierarchy of Autonomous Motivations power tool are encouraged to create awareness about what strata is currently motivating their clients and to support them if they choose to connect at a deeper level. In the words of Steve Jobs, “Your work is going to fill a large part of your life, and the only way to be truly satisfied is to do what you believe is great work. And the only way to do great work is to love what you do. If you haven’t found it yet, keep looking. Don’t settle. As with all matters of the heart, you’ll know when you find it. Don’t settle.”