A Coaching Power Tool By Austin Tay, Executive Coach, SINGAPORE

Difference Between Rigidity vs. Flexibility

What Is Rigidity?

The human species is unique as we can communicate with one another using language. We can convey our ideas, thoughts, and emotions using words that we learned throughout our lives. As we learn more words and expand our lexicon, we become prisoners to our language ability. We began to label everything we experience from bodily sensations, emotions, and even our thoughts. On the one hand, connecting all these internal experiences with an external word seems to be the default; however, our human mind takes it further. The mind will make us think that the attribution of words to our internal experience is a way to make sense of what we are going through. A form of rationality. A model that we subscribe to and follow because human beings relate best when we can explain everything with meaning. This very same demand of explaining everything creates the need to justify our thoughts and emotions, especially when negative. While the justification allows us to feel somewhat ‘normal’, the actual impact is the reverse. We get too caught up with justifying everything that we lose the ability to be open to new possibilities and move forward. Instead, we become engulfed in our rumination and vicious cycles. We become rigid in our thoughts, and that will dictate how we feel and act. The reason why we will gravitate to such rigidity in our approaches is due to associative learning. Having a curious mind, we, humans, seek to associate what we learned and link them to provide us with something that we can make sense of. So in the instance of our negative thoughts and emotions, we will look for the reasons for them and, at the same time, will associate them with a future event or consequence based on our belief derived from the association.

To facilitate this association, we must attribute it to our ability to describe the association through language. As children, we learn to acquire language through environmental influence. (Skinner, 1957). According to Skinner, children learn language through the association of words with meanings. They will continue to utter the words or phrases when their utterances get positively reinforced. For example, when a child says “milk”, and the mother gives the child milk. As a result, the child will understand that this is a rewarding outcome that will help develop the child’s language ability (Ambridge & Lieven, 2011). As we progress to adulthood, we begin to have the capacity to store more words and learn to reason and decipher situations and things around us. The ability to perform these various actions is due to what is called the working memory. The working memory helps the brain store and manipulate information required to understand language, learn, and reason (Baddeley, 1992). So when we are in a state of negative thinking or experiencing negative emotions, we are likely to search within our brain for the words to describe our state. While the labeling can be helpful if we just recognize them, the overemphasis of the meaning of words can create catastrophic outcomes. We will actively try to justify bad situations, our negative thoughts, and our emotions with words that might further exacerbate the state that we are in. We will start to dig into a bottomless pit that allows us to perpetuate the vicious cycle that prevents us from looking at possibilities of change resulting in rigidity.

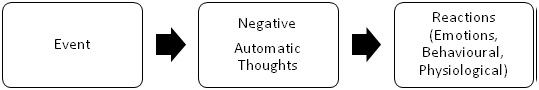

According to the cognitive model, peoples’ emotions, behaviors and physiology are caused by construing an event. (Beck, 1964; Ellis, 1962). That is to say, different people will have different reactions and feelings and will behave differently in similar situations. Therefore, these reactions and feelings are a product of our automatic thoughts.

When a person faces a situation, the mind will assimilate all the information available to make sense of it. The assimilation is done so with deliberation, or in other words, reasoning, which Fernyhough (1996) categorized as ‘dialogic thinking’ – that is, thinking done as an internalized, mediated activity. On a different level, the mind can also come up with spontaneous thoughts (automatic thoughts). When this happens, the next thing that follows will be a reaction to that thought. For example, when a person thinks that they have achieved something great, they will be happy (an emotion) and may begin to dance (a behavior). It is all well and good when an automatic thought elicits positive emotions and behavior. The problem arises when such automatic thoughts become negative. When people have negative automatic thoughts (NATS), they will feel sad (emotion) and avoid talking to anyone. (behavior).

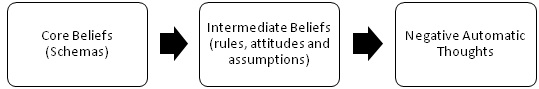

How a person generates automatic thoughts is connected with the fundamental beliefs he holds. All fundamental beliefs are molded throughout our childhood to adulthood through the things we learn and the people we observe. As time passes, all these beliefs become part of who we are, what we stand for, and how we behave. They become more pronounced when a person is psychologically distressed because their thoughts will be ‘more rigid and distorted, the judgments made will become overgeneralized and absolute which will, in turn, make the person’s beliefs of themselves and the world very fixed’ (Weisharr, 1996).

As a person’s core beliefs become stronger, he will create ‘an intermediate class of beliefs: attitude, rule and assumptions’ (Beck, 2011). These beliefs will help the individual to navigate their thought processes, emotional expression, and behavior. An example of the application of intermediate beliefs is as follows:

Attitude: ‘I panic if I do not submit my project on time.’

Rule: ‘Give up if the workload proves to be unattainable’

Assumptions: ‘If I do not have time, I will not be able to complete the task.’

According to Rosen (1988), people function adaptively and make sense of their environment by logically organizing their experiences. However, primed by their genetic dispositions, the beliefs they form through their interactions with the world and other people might not necessarily be functional and realistic.

According to Rosen (1988), people function adaptively and make sense of their environment by logically organizing their experiences. However, primed by their genetic dispositions, the beliefs they form through their interactions with the world and other people might not necessarily be functional and realistic.

When an individual faces a situation, negative automatic thoughts surface because of the individual’s existing beliefs. When negative automatic thoughts occur, an individual will respond either emotionally or physiologically, which produces a behavior. According to Greenberger and Padesky (1995), these five aspects (events, negative automatic thoughts, emotional, behavioral, and physiological reactions) of a person’s life experience can interact with one another. Therefore, the understanding of how they interact can be helpful for a person to have insight into their problem. However, when a person does not draw any insights into their issues, then this is where they will remain stuck and find it difficult to see any solutions.

When an individual faces a situation, negative automatic thoughts surface because of the individual’s existing beliefs. When negative automatic thoughts occur, an individual will respond either emotionally or physiologically, which produces a behavior. According to Greenberger and Padesky (1995), these five aspects (events, negative automatic thoughts, emotional, behavioral, and physiological reactions) of a person’s life experience can interact with one another. Therefore, the understanding of how they interact can be helpful for a person to have insight into their problem. However, when a person does not draw any insights into their issues, then this is where they will remain stuck and find it difficult to see any solutions.

What Is Flexibility?

Being flexible can be a feat for human beings because we, humans, as the status quo.

We feel more at ease when we are in a set pattern, even when the pattern makes us feel stuck. Therefore, we can start by recognizing the benefits of being flexible in perceiving things, situations, thoughts, and emotions.

One of the benefits of being flexible is to step out of the vicious cycle of rumination and catastrophizing that humans are prone to have. The act of stepping out of the cycle can help to provide a new perspective allowing us to review the very thing that got us to get stuck in the first place. With new perspectives, new opportunities ensue. We now have new options or new solutions to deal with our issues.

When we are flexible, we become adaptable to a situation with openness, awareness, and focus. We will then start to take effective action, guided by our values, to tackle any issues that come our way. So how do we go about being flexible?

A few ways we can incorporate in our lives to become flexible include: knowing ourselves better (our physical self and our thinking self), not being avoidant, self-acceptance, and committed action.

Knowing Ourselves

Knowing ourselves better requires us to notice. We need to notice what is around us, what we hear, see and think, and how our body responds to all these. All these help us to pay attention to how we observe ourselves. When we can do this without being caught up with other distractions, we will understand how to navigate and not get too caught up with what goes on around us but focus more on what makes us move forward.

Not Being Avoidant

It is natural for us to react when we find ourselves in unpleasant situations. When we start to take control, our primary aim is to curb those unwanted thoughts and emotions. Therefore we will implement control strategies. They can include flight (hide, ignore or escape) and fight (suppress, argue, take charge, or self-bully) strategies. While these strategies can serve us momentarily, they are problematic. Humans, as such, are not good at gauging excessiveness. As a result, we tend to overuse coping strategies, use them in situations that might not necessarily work, and are overly dependent on the strategy that can stop us from doing the things we value. When we are avoidant, we create vicious cycles, which can lead us to depression, anxiety, alcohol addiction (Freels, Richman &Rospenda, 2005; Rospenda, Fujishiro, Shannon, & Richman 2008), eating disorders (Townend, 2008), and other types of psychological problems. For us not to be avoidant when we encounter negativity, we can embrace such negativity as part of who we are and how we navigate as human beings.

Self-Acceptance

Self-acceptance is to be okay with who we are—showing kindness and compassion to ourselves—recognizing that we are just humans, and embracing our imperfections. We will mess up and make mistakes at some point in our lives, but most importantly, we can learn from those situations. Accepting ourselves means focusing on recognizing our strengths and weaknesses instead of judging ourselves and becoming who we want to be. Our minds will concoct and weave stories about who we are, and we have the choice not to believe them. Instead, we can choose to work on actions that can help us create meaningfulness in our lives devoid of self-sabotage, self-judgment, and self-deprecation.

Committed Actions

To be able to live a life that is rich and meaningful, it is important to take committed action. We are not talking about just taking any action. The committed actions we carry out are guided and motivated by our values – that is what matters to us. Committed actions are not one-time actions. We will repeatedly take action, regardless of how many times we have failed or when we have failed to stay on track. Along the road to taking those committed actions, our doubts, low self-esteem and fears will challenge us. When we succumb to them, we give up.

Rigidity vs. Flexibility – You Have a Choice

Human beings are intelligent and we sometimes make the choices that serve us best at a particular time. However, not all choices that we make will provide the same outcome. What matters is that when we are making those choices, we need to ask ourselves one fundamental question – When we are in an unpleasant situation, what choice can carry us through the situation?

References

Baddeley, A. Working Memory. Science

Beck, A. T. Thinking and depression: II. Theory and therapy. Archives of General Psychiatry

Beck, J. S. Cognitive behavior therapy: Basics and beyond. Guilford Press.

Ellis, A. Reason, and Emotion in Psychotherapy. Secaucus, NJ: Citadel Press.

Evans, J.M.G., Hollon, S.D., DeRubeis, R.J., Piasecki, J.M., Grove, W.M., Garvey, M.J., et al. Different relapses following cognitive therapy and pharmacology for depression. Archives of General Psychiatry

Fernyhough, C. The dialogic mind: A dialogic approach to the higher mental functions. New Ideas in Psychology

Freels, S. A., Richman, J.A., &Rospenda, K. M. Gender differences in the causal direction between workplace harassment and drinking. Addictive Behaviors

Greenberger, D. &Padesky, C.A. Mind over Mood. New York: Guilford.

Hollon, S. D., DeRubeis, R. J., & Seligman, M. E. P. Cognitive therapy and the prevention of depression. Applied And Preventive Psychiatry

Rospenda, K. M., Fujishiro, K., Shannon, C. A., & Richman, J. A. Workplace harassment, stress, and drinking behavior over time: Gender differences in a national sample. Addictive Behaviors

Rosen, H. The constructivist-development paradigm. In R.A. Dorfman (Ed), Paradigms of clinical social work. New York: Brunner/Mazel.

Skinner, B.F. Verbal behavior. Acton, MA: Copley Publishing Group.

Townend, A. Understanding and addressing bullying in the workplace. Industrial and Commercial Training

Weisharr, M. E. "Developments in Cognitive Therapy' in W.Dryden (ed.), Developments in Psychotherapy: Historical Perspectives. London: Sage Publication.