A Coaching Power Tool Created by Oleksandr Zeleniuk

(Executive and Leadership Coach, UKRAINE)

What we do every day matters more than what we do once in a while. Gretchen Rubin

Too often clients think that one decisive action can substitute a chain of consecutive efforts or discipline. It may presume that those clients believe unconsciously in the possibility that one-time great and proper effort, a “giant stride”, will solve a problem they face right from the jump and therefore, behave accordingly. As a rule, the “giant stride” is associated with either an action remote in time or any important activity for the client. However, most of the time those“giant strides” actions either fail to deliver the desired outcome or are rather mental or imaginative than real, bringing no changes in their behavior and not leading to any tangible results.

Clients’ beliefs in “giant stride” could as well masque/cover some fears as if this determined effort can eliminate the client’s issue out of his agenda. Under this masque of certitude, some underlying beliefs (UBs) are hidden. Those beliefs are used often as an excuse for different forms of inaction or an ineffective behavior like, for example, procrastination. Over 80 percent of college students are plagued by procrastination, requiring epic all-nighters to finish papers and prepare for tests. Roughly 20 percent of adults report being a chronic procrastinator.[1]

Clients with a “giant stride” way of thinking and/or behavior may obtain even benefits from it. From a neuroscience point of view, if a person plans something it causes dopamine release, letting him or her being satisfied just with some feelings of progress nesting in his/her head.

“Dopamine is released not only when you experience pleasure, but also when you anticipate it. … Interestingly, the reward system that is activated in the brain when you receive a reward is the same system that is activated when you anticipate a reward. This is one reason the anticipation of an experience can often feel better than the attainment of it. As a child, thinking about Christmas morning can be better than opening the gifts. As an adult, daydreaming about an upcoming vacation can be more enjoyable than actually being on vacation. Scientists refer to this as the difference between “wanting” and “liking”.[2]

A“giant stride” thinking may be identified when a client declares of having a “silver bullet” solution, a “magic” short-cut, an effective diet to name a few. In the long run, this type of behavior resembles shifting from one “giant stride” to another without having any tangible results for him or her. Eventually “giant strider” becomes a hostage of his/her way of thinking, trapping into a never-ending vicious circle of delaying and postponing. Meanwhile, this type of thinking deprives the client of enjoying the current moment and being in the present. It is the way to maintain a life without seemingly big losses although without long-term and sustainable progress.

I fall sometimes into this pattern too. Writing about it is a good way to raise awareness, find and apply technics that help change perspective. Working on this power tool is like having self-coaching by providing myself with a space to think, face it bravely, and letting myself being mindful.

Despite being destructive by its nature, “giant stride” thinking and behavior bring its bearer some sort of fancied relief, feeling of avoidance and substitution of necessary steps to take. This way of thinking contains an erroneous idea of a seemingly easy way to achieve results by applying one-time effort. Our brain often plays tricks with us misrelating an ambitious goal with a proper scale of effort or activity.

After a while, however, a reality check reveals that expectations do not match with the actual situation, returning the person to the initial point and causing even more stress and anxiety. Having a temporary relief from the pressure of the goal, thanks to a dopamine dose injection after imagining its accomplishing, the reality check with no obvious or satisfactory progress towards the goal brings with it a portion of cortisol (stress hormone) making feel disappointed and even frustrated.

In other words, a system of self-discipline implemented by regular small efforts wins over a mastery “giant stride”. The outstanding results are demonstrated by those who put their efforts regularly and relentlessly, no matter how small were the initial ones. Only smart persistence could benefit its bearer in the long run.

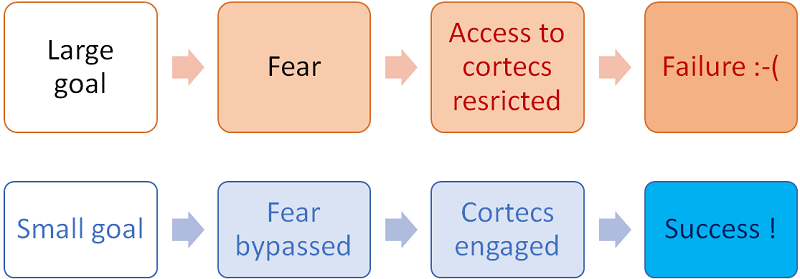

The effectiveness of small steps has an explanation with neuroscience help. Robert Maurer shares the following scheme (please, See Fig.1) and comments: [3]

“The little steps … are a kind of stealth solution to this quality of the brain. Small, easily achievable goals-such as picking up and storing just one paper clip on a chronically messy desk-let you tiptoe right past the amygdala, keeping it asleep and unable to set off alarm bells. As your small steps continue and your cortex starts working, the brain begins to create “software” for your desired change, actually laying down new nerve pathways and building new habits. Soon, your resistance to change begins to weaken.”

Figure 1. Brain comparative processing of different goals

Our brain is featured to resist change. However, by taking small steps, it is possible to rewire effectively our nervous system. Small steps enable us to “unstick” from a creative block, bypass the fight-or-flight response. These actions “below the radar” create new connections between neurons enabling the brain to take control of the process of change and letting us progress rapidly toward our goal.

Coaching application

The key elements of the Power Tool application process, helping the coach navigate through, are:

- Identifying(with appropriate exploration)unproductive pattern of inaction or delaying action.

Trust and intimacy, coaching presence and active listening are among the first competencies the coach employs to do it. The coach pays attention to the client’s words, discrepancies between the client’s current and desired results.

- Creating awareness.

When the coach recognizes an unproductive pattern of “giant stride” thinking, he or she turns to direct communication, sharing observations, perceptions, comments, thoughts, and feelings that serve the client’s learning.

To explore further the observed signs of client’s thinking and/or behavior, the coach may ask the following questions relevant to the client’s situation:

By inviting the client to share his/her learning about his/her way of thinking, behavior, and current, presumably unsatisfactory, outcome, the coach reinforces the client’s awareness, letting the client find the ground to change his views, assumptions, and behavioral patterns.

- Changing perspective.

At the point when the client looks (sounds or feels) as if he/she is getting aware of his/her patterns of thinking and acting, he/she can tap into his/her untouched potential and source of empowering energy.

At this stage coach’s task is to partner with the client in finding a trigger (or switch) that converts the client’s learning about him/herself and his/her situation into small but regular steps. The “action” here means different(other than before) client’s mental and behavioral models leading him/her to the desired outcome.

- Designing actions

This is a turning point when the client can focus his/her attention on designing a set of actions as well as a support system that lead to the desired objective. As soon as the client starts outlining his/her action, the coach applies competencies (9, 10, and 11) related to envisaging possible obstacles and elaborating the contingency plan to overcome them.

The coach may ask the client while keeping in mind his/her goal, the following questions:

When the action plan becomes tangible, the coach assists the client to elaborate on the best methods of accountability for her/himself.

Conclusion

A person can stimulate the joy (thanks to dopamine) and sustain moving forward toward a goal by taking even baby steps. Results may be unpredictable at the beginning of taking action, but it is always possible to adjust expectations and take another step forward. This power tool is not a discovered lifehack but an approach based on and supported by neuroscience. Thinking on this approach and coming across different reading materials bring more and more evidence of its effectiveness. My personal experience proved this in learning foreign languages, sustaining personal physical training program,s and adopting new healthy eating habits.

References:

[1]“Why I Taught Myself to Procrastinate” by Adam Grant

https://www.nytimes.com/2016/01/17/opinion/sunday/why-i-taught-myself-to-procrastinate.html

[2]James Clear. (2018). Tiny Changes, Remarkable Results. Atomic Habits: An Easy & Proven Way to Build Good Habits & Break Bad Ones. Penguin Random House.

[3]Robert Maurer. (2004) One Small Step Can Change Your Life: The Kaizen Way. Workman Publishing Company