A Coaching Power Tool Created by Mark Johnson

(Spiritual Coach, USA)

Engaging Our Non-Dualistic Level Of Awareness

The basic premise of this Power Tool is that one of the principal ways we can help our coaching clients is through helping them remove apparent obstacles to their goals. While it is obvious that we all have practical, real world obstacles to achieving a dream, say, enough money to pay for college tuition, or sufficient health to run two miles every day, it is equally obvious that we ourselves hamper and hinder our own progress through creating psychological obstacles, or by being unable to remove dysfunctional mindsets.

There are many ways of thinking about resolving psychological or mental blocks, and the literature of psychology and coaching is rife with them. Here we will draw upon Eastern wisdom traditions as our source for the Power Tool. In so doing I hope to call attention to a higher level of awareness and meta-cognition, the spiritual faculty of non-dualistic thinking.

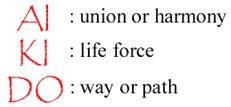

Mental Aikido

To introduce this concept of non-dualistic problem solving and goal setting I want to begin with an analogy to a martial arts discipline. I call this ‘Mental Aikido,’ because in the non-aggressive, internal martial arts like Aikido, students are taught to relax completely and to learn how to control their own aggressive tendencies. Aikido is as much a mind training as it is a martial art. Aggression, tension, anger, and competitiveness are all understood in Aikido, as in its Chinese cousin, T’ai Chi Chuan, as mental elements which make us only physically weaker and less coordinated. Moreover, by taking the opponents’ own aggression and turning it away from a strike, by uprooting and disabling the opponent, the Aikido practioner consistently tries to keep in mind that their task is not only to defend themselves, but also to not seriously damage the aggressor. So, too, must we handle our own conflicted way of thinking.

Aikido carries this non-dual way of thinking into its whole philosophy, thereby cultivating a view of the world and the human psyche as inherently in harmony with nature, and not opposed to it. This is a view radically different from prevailing concepts in the Western world that we must “conquer” nature, that we must combat ‘the enemy,’ whoever we imagine them to be: our fears and weaknesses, our business competitors, our internal or external obstacles or whoever or whatever it is that we believe we have to “overcome.”

In the same way that Aikido approaches aggression from the outside, this Power Tool asks the client to become less annoyed by, or antagonistic to, the obstacles that inevitably come up in our own internal process, whether they be emotional, intellectual, moral, professional, or spiritual. By this approach we learn how to first view the obstacle not as an enemy, but rather as a puzzle needing to be solved, or a mystery to be deciphered, and eventually as a friend who taught us something irreplaceable about ourselves.

In the same way that Aikido approaches aggression from the outside, this Power Tool asks the client to become less annoyed by, or antagonistic to, the obstacles that inevitably come up in our own internal process, whether they be emotional, intellectual, moral, professional, or spiritual. By this approach we learn how to first view the obstacle not as an enemy, but rather as a puzzle needing to be solved, or a mystery to be deciphered, and eventually as a friend who taught us something irreplaceable about ourselves.

By learning how to analyze these problems non-dualistically, we can help our clients move through them more gracefully and efficiently. This is the opposite of a conventional battle analogy, as we said above, where we have to “defeat” our obstacles, or “power through” the resistances, or whatever else the mental mindset creates.

What we are offering here is more a thinking-about-thinking approach, one that hopes to shift the perspective of the client from seeing obstacles or mental dilemmas as antagonistic opponents, to an understanding that these are only apparent contradictions, these seemingly opposing forces are in reality just two sides of the same coin, each having equal and lasting validity, and one way to free ourselves from mental conflict is to deepen our understanding of non-dualism.

In addition, this is essentially a spiritual approach to dealing with obstacles because it integrates multiple levels of awareness, including a higher order of consciousness. As I hope to offer my coaching practice to people in the spiritual community, and especially the Buddhist community, I would present this method to those clients who have already identified themselves as being open to working from the integral point-of-view — one that sees awareness as co-existing spiritually, mentally, emotionally and physically.

I believe that by helping a client adopt a non-dualistic approach to problem solving and goal setting we help them activate their own spiritual resources — precisely because the only way to really think about problem solving non-dualistically is from a spiritual point of view. This, in turn, helps the client align with their core spiritual values, for example, non-harm, or non-violence, or right action and right speech. By creating a coaching atmosphere that encourages this non-competitive, non-violent approach to thinking-about-thinking, we help the client become less aggressive to themselves, and that posture should emanate outwardly into all their interactions in the world.

The Japanese founder of Aikido, Morihei Ueshiba, manifested this way of life by being extraordinarily gentle, and overt in his teaching that Aikido was founded on spiritual principles. He was beloved by thousands of students, and often converted opponents who he defeated in competition to becoming his pupils.

The Spiritual Philosophy of Aikido

That Ueshiba believed Aikido was a spiritual path is evidenced by the great emphasis he made on the role of the spirit in the martial arts. As Wikipedia says,

Ueshiba developed aikido after experiencing three instances of spiritual awakening. The first happened in 1925, after Ueshiba had defeated a naval officer’s bokken (wooden katana) attacks unarmed and without hurting the officer. Ueshiba then walked to his garden and had a spiritual awakening.

I felt the universe suddenly quake, and that a golden spirit sprang up from the ground, veiled my body, and changed my body into a golden one. At the same time my body became light. I was able to understand the whispering of the birds, and was clearly aware of the mind of God, the creator of the universe.

At that moment I was enlightened: the source of budō [the martial way] is God’s love – the spirit of loving protection for all beings …

Budō is not the felling of an opponent by force; nor is it a tool to lead the world to destruction with arms. True Budō is to accept the spirit of the universe, keep the peace of the world, correctly produce, protect and cultivate all beings in nature.

His second experience occurred in 1940 when engaged in the ritual purification process of misogi.

Around 2 am as I was performing misogi, I suddenly forgot all the martial techniques I had ever learned. The techniques of my teachers appeared completely new. Now they were vehicles for the cultivation of life, knowledge, and virtue, not devices to throw people with.

His third experience was in 1942 during the worst fighting of World War II, Ueshiba had a vision of the “Great Spirit of Peace”.

The Way of the Warrior has been misunderstood. It is not a means to kill and destroy others. Those who seek to compete and better one another are making a terrible mistake. To smash, injure, or destroy is the worst thing a human being can do. The real Way of a Warrior is to prevent such slaughter – it is the Art of Peace, the power of love.

Self-Application

We can experience this mental Aikido by taking an example from our own lives where we feel trapped by a “damned if I do, and damned if I don’t. . .” belief system. One of the ways we can visualize this Aikido-like approach to problem solving is through using the symbol of the Yin and Yang.

All of us are familiar, at least visually, with the symbol of the Yin and Yang, what is called the Taijitu in Daoist philosophy. Commonly, we look at it as symbolizing day and night, hot and cold, as a visual prompt for understanding the balance between opposing forces. But let’s look a little bit deeper. As the article in Wikipedia says:

Yin and yang can be thought of as complementary (rather than opposing) forces that interact to form a dynamic system in which the whole is greater than the assembled parts. . . Either of the two major aspects may manifest more strongly in a particular object, depending on the criterion of the observation. The yin yang shows a balance between two opposites . . .

In Daoist metaphysics, distinctions between good and bad, along with other dichotomous moral judgments, are perceptual, not real; so, the duality of yin and yang is an indivisible whole.

In the second paragraph we note the comment that in the Daoist metaphysical tradition, moralistic analysis between what is

In the second paragraph we note the comment that in the Daoist metaphysical tradition, moralistic analysis between what is

good and bad, along with other dichotomous moral judgments, are perceptual, not real. . .