A Coaching Power Tool Created by Joanne Lee

(Health and Leadership Coach, AUSTRALIA)

Between stimulus and response, there is a space. In that space lies our freedom and power to choose our response. In our response lies our growth and freedom. Viktor Frankl

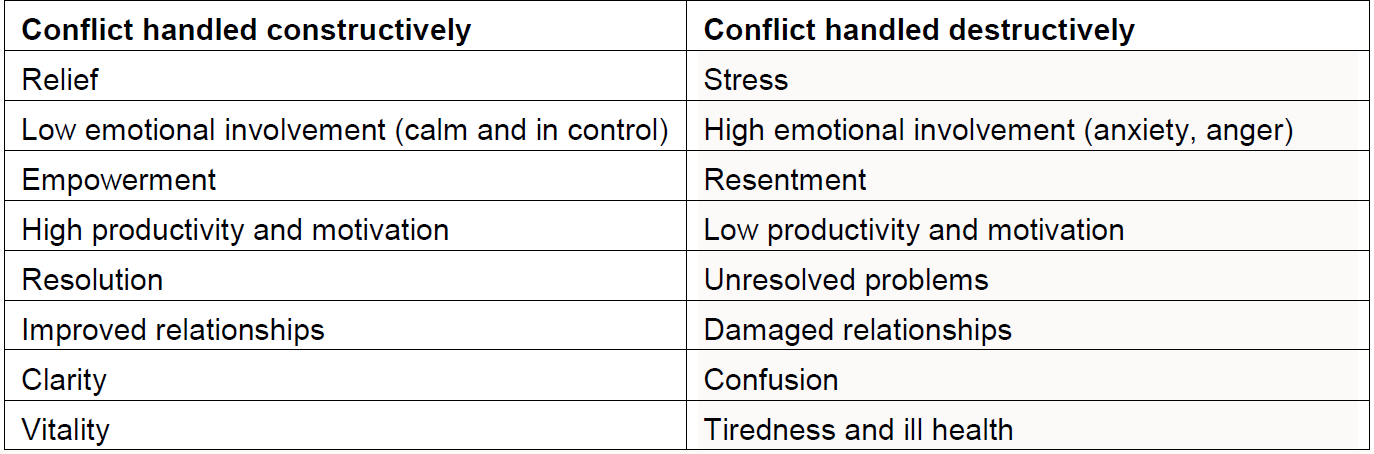

Conflict occurs when two or more people see their needs, ideas or values as competing or incompatible. It can cause a variety of strong, and often negative emotions – such as abusive arguments, anger, distrust, disappointment, frustration, confusion, worry, or fear. Conflict is an inevitable part of life. It happens to us all. As individuals with different needs, values, ideas, views, tastes and personalities, sooner or later we’re bound to clash. It’s not the presence of conflict that is the problem; it is how we deal with it which determines whether it is problematic or not (Table 1). In fact, conflict can be a catalyst for real and lasting change: it has often helped people to make better decisions because it helps them to identify situations that no longer serve them. Thus, conflict can be positive or negative, constructive or destructive depending on how we handle it.

Table 1: What happens when conflict is handled constructively versus destructively.

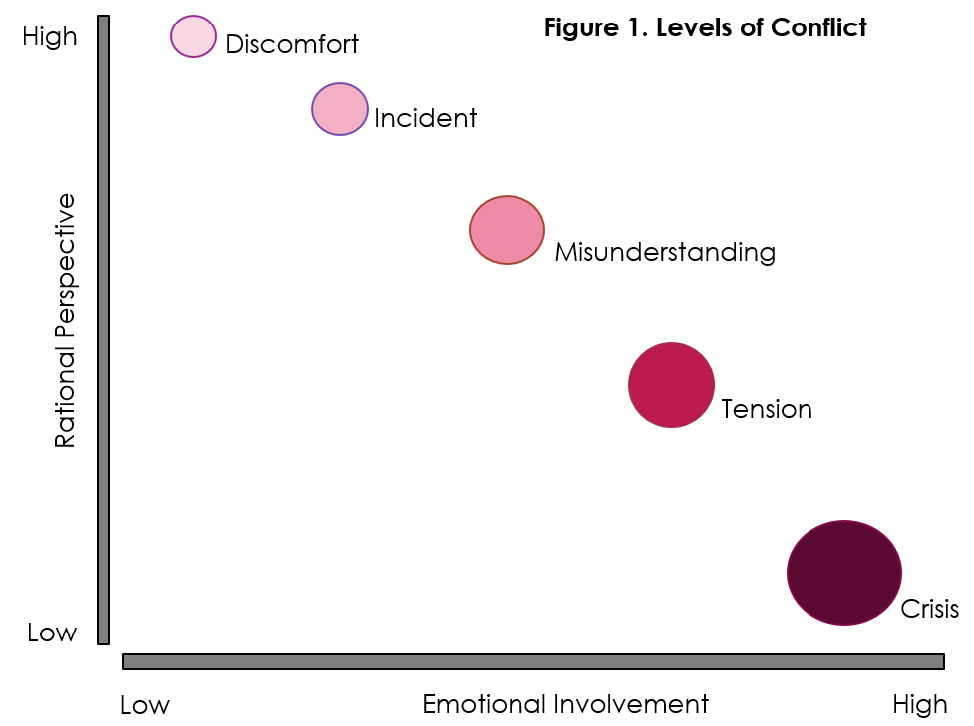

Vitality Tiredness and ill health Typically, conflict occurs in escalating levels of seriousness. Five progressive stages are observed; these are: discomfort, incident, misunderstanding, tension and crisis (Figure 1). Many destructive behaviours (as a result of unresolved conflict) can be prevented by early attention to conflict clues. Discomfort – slightly negative emotions – alert us to the reality that a situation of conflict is occurring. It is easier to deal with the issues at this stage because people tend to look for objective solutions in a cooperative manner. At the other end of the spectrum – crisis – emotions are at boiling point. Heated or abusive arguments are a sure sign of crisis. During this stage, objectivity goes out the window so people are unable to see things clearly. Mediation is often necessary to address issues.

One may ask ‘why can’t we see the woods for the trees’ when we are furious? As conflict escalates through various stages, people’s behaviours gradually regress from mature to an immature level of emotional development. When our emotional involvement is low (e.g., calm), our rational perspective is high because it is easier to engage our rational brain (prefrontal cortex). But, when the emotional involvement is high (e.g., anger), our rational perspective is low because it is harder to engage the rational brain. In fact, when we perceive threat (psychological or physical), our primitive brain (amygdala) assumes control and kicks off a ‘fight or flight’ response. The amygdala is our survival watchdog and decides if we should get angry or fearful, and the prefrontal cortex is the part that makes you stop, think and find solutions. So, the key here is learning to engage our rational brain in the moment of conflict so the amygdala doesn’t get overstimulated or assume control.

Each of us view the world through our own perception of reality – through our own lens. This is based on our learned/taught standards and values, personal experience, and the meaning (views and beliefs) we give events as a result of these. Once we own our own experience of reality, we realise that we have a choice in any given situation. We choose either to be constructive or not, in our approach. If we react to others defensively by attacking or withdrawing, conflict can rapidly escalate from one of discomfort to crisis e.g., angry outburst, heated arguments or violence. If, instead, we respond appropriately, we can help to bring the emotions to a level at which the issue can be dealt with more constructively.

How might you go about owning your experiences and perceptions?

Reflection exercise:

Take some time out to consider a conflict situation you recently faced.

- How did the situation affect you personally?

- What was the outcome of the situation?

- On a scale of 1-10 (1=low and 10 = high) how emotionally involved were you?

- Using the same scale, where would you rate your rational perspective of the situation?

- How would someone who was less emotionally involved have seen the situation?

- How would responding differently have affected the outcome and consequences?

- Think of three other responses you could have made in that situation?

- What are your reflections on doing this exercise?

Moving out of Reaction Constructively:

Techniques such as centering, visualisation exercises, mindfulness, meditation, reflection and reframing perspectives appear to calm our inner tensions associated with conflict threats and provide us with a way to regain emotional balance. These techniques focus on activating or strengthening the prefrontal cortex which in turn counteracts our ‘fight or flight’ response by toning down the amygdala. Put simply, it slows or shuts down unnecessary instincts and emotions, while activating rational thinking.

Retrain your Brain

Building Self-Awareness

Know your Triggers and Early Conflict Clues You can’t stop someone from pushing your buttons if you don’t recognize when it’s happening, or the thoughts, feelings and physical responses that comes with it. So managing your emotions and remaining calm under stress requires awareness.

1. Learn your “conflict triggers” What situations push your buttons? What situations make you prone to losing your temper? When and where does it happen?

2. Identify your “early warning signals” You can spot warning signs in your body, emotions and thoughts. Examples are below.

Body

Emotions

Thoughts

Reflect and Reframe your Perspective

Resources:

McGee, Paul. S.U.M.O (Shut Up, Move On): The Straight-Talking Guide to Succeeding in Life.

Helena Cornelius and Shoshana Faire. Everyone Can Win: Responding to Conflict Constructively.

http://www.talentsmart.com/articles/How-to-Stay-Focused,-Calm,-and-Productive-299644652-p-1.html

https://www.rewireme.com/insight/train-your-brain-how-to-reduce-anxiety-through-mindfulness-and-meditation/