A Coaching Power Tool Created by Helen van Ameyde

(Business Coach, BELGIUM)

A coaching power tool: What is real versus imagined?

Our imagination is extraordinary: it can help us innovate, learn, love, create, and conversely worry, fear, panic, and criticize. Anything is possible, and the story we tell ourselves can build from a word, a look, a feeling, a memory, any interaction (or lack of one). The positive and negative impacts of imagination are endlessly damaging and infinitely positive and fulfilling, in sometimes equal measure.

How many times have we made a decision, acted in a certain way, assumed something about a situation that turned out to be wrong, and based on a faulty set of data? I know I have.

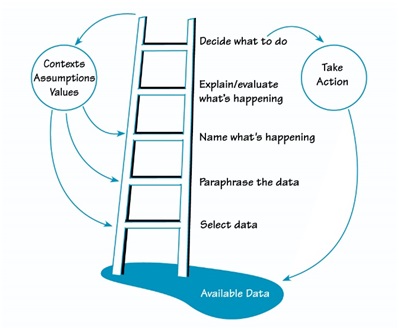

The Ladder of Inference(first developed by the American Chris Argyris, a former professor at Harvard Business School in 1970, and made famous in Peter Senge’sand Argyris’ book The fifth discipline) explains why we do the things we do and why we behave in certain ways. It provides insight into the mental processes that occur within the human brain: describing the perception starting from information that is taken in by our senses, to the series of mental steps taken towards an action. This human thought process only takes a fraction of a second, happens subconsciously and often people do not realize how they developed a particular action or response. The Ladder of Inference determines what you see and how you take in facts, how your thought processes work, and therefore how behavior (action) happens. People, all humans give meaning to observations and then base their actions on their perception and understanding of them.

The Ladder of Inference consists of seven steps and the reasoning process starts at the bottom of the ladder, on the first rung. People ‘sensemaking’ of what they see and hear, they select facts from events and use their experience and knowledge to understand and contextualize. The problem is that the sense-making is based on heuristics (our ability to short cut decision making), and our unconscious bias. Interpreted facts form the basis for our assumptions and this, in turn, leads to certain conclusions that can then form the basis for decision-making and action.

The Ladder of Inference explained:

Level 1. Reality and facts

This level identifies what is directly perceptible; all data is readily available, one can see, hear, feel, smell, and touch information from the real world.

Level 2. Selecting facts

At this level, facts are selected based on personal convictions and prior experience. We choose to abstract data from situations based on our frame of reference i.e. what we understand and what we know.

Level 3. Interpreting facts

Facts are interpreted and given a personal meaning. Individuals form conscious awareness of certain groups of people and situations based on their unconscious bias (Daniel Kahneman). Everyone holds unconscious beliefs about people and situations, and these biases stem from one’s tendency to organize social worlds through categorization. This categorization influences how we interpret facts, and therefore our understanding of the context, the people, and the situation.

Level 4. Assumptions

At this level, assumptions are made based on the meaning one gives to individual observations. These assumptions are personal, based on our worldview and are different for every individual.

Level 5. Conclusions

At this level, conclusions are drawn based on prior beliefs and experiences.

Level 6. Beliefs

Facts are interpreted and assumptions made to confirm what we believe to be true.

Level 7. Actions

Actions are now taken based on prior beliefs and conclusions. The actions that are taken are considered to be the best for that situation at that particular time because an individual will have decided (almost subconsciously) based on Level 1 – the available data. Unconscious bias then plays another role in confirming the decision by seeking out information that confirms the ‘truth’ and this is called confirmation bias.

The Ladder of Inference, Chris Argyris and Peter Senge

The Ladder of Inference, Chris Argyris and Peter Senge

The mind is a wonderful instrument: it helps us make decisions so that we can move through the world and cope with the mass of stimuli coming at us every day. However, the tendency to rely on what we choose (imagined) over what is (real) is stronger than we know. There is a negative impact of speedy decision-making that influences the stories we tell ourselves, and therefore the decisions we make.

The contradictory nature of our imagination: flights of fancy and gloomy despair come from the real and the imagined, and starts at the bottom of the ladder – ‘available data’ i.e. that which one observes and experiences. We take in data (we see, hear, feel, read), we select and interpret the data ‘confirming’ what we know (my colleague said this, and therefore thinks that) to be ‘true’. We make assumptions, form conclusions, and take action. Most of the time this is done subconsciously and our negative and positive stories continue to build, take shape, and form part of our bank of experience and data to be drawn on and used in a different time and place. Thus, we create a cycle – sometimes healthy, sometimes not.

Coaching can help us take time out to reflect on why our internal story is telling us the tale it is, and help you challenge your thinking before you do, say, or think anything that isn’t helpful.

So the next time your thoughts, beliefs, and actions are based on what you ‘know to be true’, take a moment to challenge where the data is coming from and how it helps your narrative develop into negative or positive actions.

So the next time your thoughts, beliefs, and actions are based on what you ‘know to be true’, take a moment to challenge where the data is coming from and how it helps your narrative develop into negative or positive actions.

Application

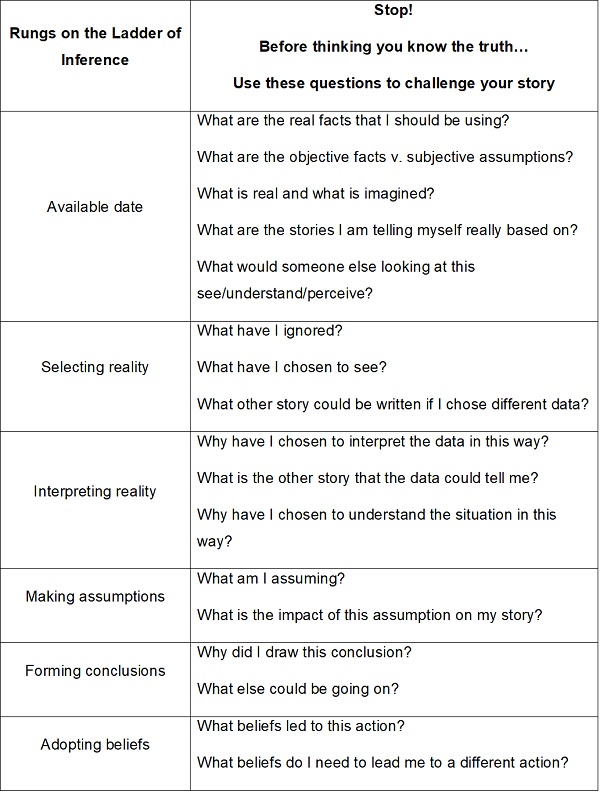

These questions can be useful to challenge the story, the self-talk, and any limiting beliefs that come to mind because of our stories. In a recent coaching conversation, the conversation turned to, ‘how one should act in a more senior role’. The view was that a new role required a more serious, more grown-up, less open person. A person is less able to reveal their true selves, as their true self was often ‘juvenile, jokey and fun’ and ‘wouldn’t be tolerated in the C suite’. My client had convinced himself that in order to be successful in the new role, he would have to change and move away from what he believed was his authentic self.

The application of the power tool, ‘real vs imagined’, through the use of powerful questions helped the individual sort the data, analyze what is and is not, challenge assumptions, decisions, and therefore the resultant action. The tool helped the individual reflect, learn from experience, and build a different, more helpful narrative.

In the example above, the following questions explored the client’s feelings on their readiness for the promotion:

It was a powerful conversation and one that helped the person see and understand that their reality and the subsequent story was not based on objective data and clear evidence. On the contrary, it was based on subjective data, observation (through a particular lens), their own perceived failure and successes, and what they thought people would say and think. Their imagination had been working overtime to describe an imagined reality based on self-talk, beliefs, and perceptions of their own ability. The imagined story was different from reality and using the ladder of inference helped the individual understand the negative impact of the cycle they had created.

Reflection

I know that I have my own narrative about certain things: whether I am good enough to do X, whether I should have the job I do, whether I can really write this essay about Power Tools. I know it is there, and I also know about objective facts and subjective narratives. What is interesting is to think about why the negative self-talk often takes precedence over the positive thinking processes.

Challenging my own narrative is my work in process, what works for me is to regularly take time out to reflect on decision-making and my thought processes. Time permitting, if I can choose to think more and act less quickly, then I can be more certain that my decision-making is based on the real and not the imagined.

References

Argyris, C., ‘Overcoming Organizational Defenses: Facilitating Organizational Learning,’ 1st Edition, © 1990. Printed electronically and reproduced by permission of Pearson Education, Inc., Upper Saddle River, New Jersey. and Sons, Inc

Kahneman, D., ‘Thinking Fast and Slow’, 2011, Farrar, Straus and Giroux