A Coaching Model Created by Elizabeth Tuleja

(Global Leadership Coach & Cross-Cultural Management Coach, CHINA)

Coaching Niche

This coaching model is for professionals engaging in a global world – whether in business or education. )

Communication is the real work of leadership. Nitin Nohria, Dean of Harvard University

It is now a cliché to say that the world is shrinking and that we live in a global village – the world has already shrunk, and the current reality is that we live in a side-by-side global marketplace where difference and variety abound.

If you would you like to have less frustration and more satisfaction with colleagues, be more effective at work, and unlock the mystery of why interactions and relationships fall flat at work, engaging in this coaching model will help you achieve greater cultural competence – your own CQ!

Coaching Model

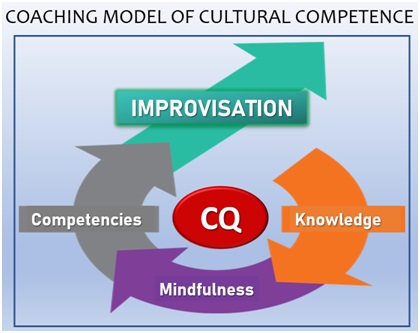

Developing cultural competence (or CQ = cultural intelligence) is like improvisation. You try one thing based upon your experience, then reflect and regroup, and try another approach.

Coaching is like improvisation – it is a fluid process that bends and twists and flows in different directions based upon the context and situation.

The model, “Components for Cultural Intelligence” is useful because of its simple yet powerful approach to developing cultural competency (CQ = Cultural Intelligence). This model posits that intercultural competence can be nurtured by gaining the necessary knowledge for cultivating successful intercultural competencies, but it is the concept of mindfulness— focused observation and critical reflection (mindfulness) —that provides the vital link between one’s knowledge and behaviour when leading across cultures.

The cultural intelligence model as construed by Thomas[1] demonstrates that developing knowledge, mindfulness, and skills (also known as competencies) working together in concert helps a person to achieve CQ. Culturally intelligent people are able to use their knowledge to understand multiple aspects of cultural phenomena that come their way; they use mindful cognitive strategies that both observe and interpret any given situation, and they develop a repertoire of skills which they can adapt and then demonstrate appropriate behaviours across a wide range of situations – it is like performing improvisation.

Knowledge

Knowledge means recognizing some fundamental principles of behaviour (customs, practices, rituals, greetings, language, etc.) and/or understanding something about a culture’s history, politics, economy, or society. One may understand how a given culture varies from one’s own, how that culture affects behaviours, what are some of the basic tenets of this culture’s belief system, or even some of the fundamental principles for how to interact with people in that culture. This is favourable to lacking knowledge about a culture; however, simply knowing about the practices of people, society or government is not enough. Human interaction is complex and countless cultural intricacies and sensitivities abound, so simply having cultural knowledge—however notable this is—is not a predictor of competence. For example, even being fluent in another language is no replacement for being sensitive to people’s beliefs and behaviours, although it is a step in the right direction.

Mindfulness

Mindfulness indicates that the transformational difference in crossing cultures is to actively pay attention to the subtle cues in cross-cultural circumstances—then to tune in to one’s prior knowledge, thoughts, feelings, actions, and reactions to what is going on. The person practising mindfulness is aware of one’s own assumptions and perceptions and the emotions and attitudes attached to them. This person will also pay attention to the other person’s actions – both implicit and explicit.

Skills/Competency

Being skilful means that a person can choose appropriate behaviours suitable for a given situation. If one has developed knowledge about the culture and how it affects behaviors, then one should be able to carefully reflect on it in order to figure out its meaning. At that point, the culturally competent person’s aim is to figure out how to apply that knowledge by putting it into appropriate actions. The knowledge that is reflected upon deeply can result in effective behaviour.

For example, the culturally intelligent person appreciates that it’s not enough to simply know that formality is important in Japan and that bowing is a key cultural practice. One must discern the different situations and degrees of bowing as well as aspects of the bow, such as its depth and length, the person’s rank, and so forth. Also, should one bow to greet, to thank, to apologize, or even to congratulate someone? As a foreigner, you may not be expected to bow, but if initiated, then you need to understand the intricate nuances of this form of communication—it is symbolic; it is ritual.

Knowing who should bow first, how low, and how long and why this should be done this way in the first place involves having prior knowledge. In addition, one must assess whether they performed the greeting correctly. Was there subtle body language that might have signalled dissatisfaction? Could positive body language—e.g., facial expressions such as a smile—mean success or could this possibly mask disapproval?). Skillfulness requires constant attention and redressing the “what” and “why” of every situation. Therefore, mindfulness is the critical link between one’s knowledge and one’s behavioural skills when leading across cultures. One must build upon knowledge and go beyond merely learning facts, then analyze one’s behaviour and reflect on it in order to build that repertoire of skilful behaviour. Without this mindful, reflective practice, knowledge is empty and results in difficulty developing the competencies needed for intercultural interactions.

Conclusion

Because this is an iterative model – one is constantly working on her or his competencies – it is a work in progress. The more we gain knowledge, practise mindfulness, and develop the skills, or competencies, to engage with difference, the more we realize that sometimes we get it right and sometimes we don’t. That is why this iterative process is all about improvisation – flexing and pivoting and changing direction and strategies for engaging with cultural differences.

[1]Thomas, David C., and Kerr Inkson,(2009). Cultural Intelligence: Living and Working Globally, (Barrett-Koehler; San Francisco, CA).