Coaching Case Study: Stewart Edmed

Coaching Case Study: Stewart Edmed

(Executive Coach, CHINA)

Impostor Syndrome

Note: The literature contains both spellings ‘impostor and imposter’. I have erred on the side of ‘or’ spelling, though where I cite a reference I leave the word in the original spelling

Introducing Jimmy

Introducing Jimmy

Jimmy today is 49, happily married for 17 years with 2 adorable children. Jimmy has four University Degrees including an MBA (came 12th of 40 in his class) and a Ph.D. (he is a scientist). He has never been out of a job and has worked at a large American Multinational Company (MNC) for 2 decades in 5 countries across Europe and the US, never had less than ‘meets expectations’ and today manages over 40 people in the R&D team across 3 laboratories. His current measure of success is just 5 years or so from financial independence, allowing him to devote time and energy to ‘whatever the hell my family and I need or want to do’. By almost any measure of society, no one would label him as professionally unsuccessful or not deserving of his respected position.

But for many years, Jimmy felt like an impostor and was waiting to be found out as such. This case study takes us through our coaching journey of 2017 from the Eureka! moment of discovery to the successful self-management of the syndrome by him today.

Definitions of the Impostor Syndrome

The original work that first reported Impostor Syndrome (originally ‘Impostor Phenomenon’) was a study on High Achieving Women in 19781. Their definition reads:

‘an internal experience of intellectual phonies…that…despite outstanding academic and professional accomplishments…persist in believing that they are not bright and have fooled anyone who thinks otherwise. Numerous achievements, which one might expect to provide ample object evidence of superior intellectual functioning, do not appear to affect the impostor belief.’.

More concise and relatable definitions include:

- ‘Impostor Syndrome is a pervasive feeling of self-doubt, insecurity, or fraudulence despite often overwhelming evidence to the contrary. It strikes smart, successful individuals’2

- ‘a false and sometimes crippling belief that one’s successes are the product of luck or fraud rather than skill’3.

In the original 1978 paper, the only cohort examined was 150 high-achieving women, but as listed in Sakulku & Alexander (2011)5 it has been demonstrated to hit all walks of life and not only working or academic environments. Instead, it is widespread and more likely to be seen in minorities within groups, typically women and/or ethnic minorities in largely male, white organizations.

How This Affected Jimmy

1998-2015: The Prologue

Up until early late 2014, Jimmy was fine and doing well. His career had blossomed, his family grew, and all was well. There were no signs of him feeling unworthy of his professional success and the roles he had were impactful and central to the success of the business around him. Only under the later coaching sessions in 2017 did Jimmy recall how during his middle Ph.D. year (in 1998) he had a sense of depression stemming from a) a split with a serious girlfriend and b) that when his studies soon ended he has no clear path forward, nor felt worthy of having any skills or experience which would make him employable. By his description, he had been studying and investing in himself for over a decade of adulthood and was not moving forward. However, barely 18 months later by the end of his final year of 1999, he had met and fallen in love with his future wife and had been sought out by contacts from the aforementioned MNC for an interview, excellent job offer, and in fact for everything Jimmy had wanted from his career choices since he was 16. These next years from 1999 to 2014 were very successful both from a personal and professional perspective, but a move to a larger job in Asia in late 2014 took Jimmy out of his comfort zone.

Spring 2015 – The Syndrome Manifests

The working atmosphere in the new job/country/environment was extremely challenging right from the start in October 2014. His line manager was old-school tough: held high standards, had higher knowledge and experience levels than Jimmy in this new arena, plus was extremely direct, critical, and negative in many decisions and actions Jimmy took. His work partners were aggressive, but his support team passive and not willing to either tell the whole truth of what was going on or help Jimmy challenge things that needed to be fixed. Jimmy reflected that he felt he could do no right. He wasn’t equipped and he had no one to understand and share this with, He had finally been promoted beyond his ability. Jimmy spent the next 2 years under extreme pressure, though as he reflects upon it today, made some significant progress as measured by the success of the business he was responsible for.

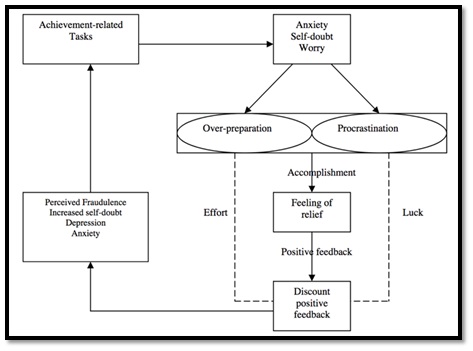

This feeling of inadequacy affected Jimmy in not speaking out at important meetings, not challenging what should have been challenged, not raising ideas, and taking the initiative. At the time Jimmy was the Company Technical Director and was responsible to lead a franchise team of over 1000 people. His apparent ‘absence’ of leadership (at least as he saw it) was failing. He would be found incompetent. At this time Jimmy was unaware, as the syndrome works cruelly in an environment of pluralistic ignorance: everyone thinks it is only felt by them. Two other key features of the syndrome hit hardest: 1) it is a reinforcing cycle of a negative feedback loop, and 2) it is purely internal: it ignores any positive external inputs that may create a break in the cycle (See Figure 1). Therefore, Impostor Syndrome is extremely hard to reverse once it becomes established.

March 2017 – Eureka

On an ordinary workday in March 2017, while checking news headlines on the BBC website, Jimmy came across a radio program titled ‘Imposter Syndrome. Have you ever felt like a fraud? Think that one day your mask will be uncovered, and everyone will know your secret? 6’. Jimmy clicked on the link and for the next 23 minutes had (as he recalls) an amazing feeling that finally, he knew what he had been experiencing. That there was a diagnosis. That he was not alone. That he could fix this. It is at this point that Jimmy reached out to get coaching help.

The Coaching Journey

Discovery & Session 1: Setting the Coaching Agreement and Initial Goal Setting

In our first coaching sessions, Jimmy was extremely happy to be talking to someone that he felt could help fix his situation, but frankly just talking to anyone who would listen and be empathic was a wonderful feeling. After establishing good chemistry, we set up a coaching agreement including session logistics, payment, frequency, and an outline of the process ahead, his role and my role, of what coaching is and what it is not. I also did my homework before the first session on Impostor Syndrome, established it was not seen as a condition requiring psychological therapy, and understood more about the symptoms to ensure we were on a reasonable track for Jimmy’s development. I felt I could help him.

At our first session, Jimmy talked non-stop for half an hour describing how the ‘symptoms fit the disease’ and concluded with ‘so what do I do now?’ I coach using the GROW model (I informed Jimmy of this and he was happy to follow this as a simple logical process), and so it was important to establish the Goal that Jimmy wanted to achieve in our time together, and that it was him that would be accountable for success: that the best and most successful solutions would come from within and I would help him discover what that will be. It has to be client-driven: to be working in the direction that he expressed he needed to discover and grow. This was done by asking questions such as ‘What does success look like for you?’, and ‘how will you measure you have made progress?’ ‘what milestones can you set?’, What image of yourself would you like to see? I also encouraged him to not only think of the outcome but also ‘what if this doesn’t work out as simple as it sounds?’ How will he deal with not consistently meeting this goal every day?’. This was important as I wanted to be sure Jimmy had the awareness and tools to deal with Impostor Syndrome if/when it came to him again.

At the end of the first session, we had established what he wanted to achieve: his goals, and I set him ‘homework’ for the next session. I asked him to go and research it as much as possible, and identify the areas and situations that resonate. I sent him some links for reading, YouTube videos (such as reference 7), and articles. As Jimmy is a scientist, logical in approach and thought, I asked him also to do 2 things: mark his situation on a scale of 1 to 10, with 1 being immobilized by this syndrome and 10 being completely free. Second, I asked him to note down incidents where he could identify when the syndrome was having its negative effect and how he would normally respond in those situations.

Session 2 – Jimmy’s Reality

In the second session, we went back over the last session’s discovery, his homework to check if Jimmy had discovered other aspects of the condition and that his goal was the same. Jimmy was able to confirm it was and related how his research had consistently supported his self-diagnosis. At the beginning of this second session I also acknowledged we had re-established the goals and that if we continued to follow the GROW process, it was next important to get a foundation for his current reality, to be clear of his starting point on this journey.

He also related that he felt a 3 out of 10 in terms of the effect of the syndrome, though it fluctuated from 1-to 6 depending on his situation. As I listened actively and asked Jimmy powerful questions to lead him further and deeper in awareness, Jimmy also talked through incidences where afterward he knew what the right thing was to say, but he was reticent to say anything and seem foolish. He also related how compared to his peers many of them came up with excellent ideas and observations that he should have brought up. He felt he never came up with smart observations or ideas. I challenged that. ‘Really’? After a long pause, he did start to recall some incidences when he had noted and remarked on something that was well received. His body language changed, he sat up and became animated, excited. He smiled inwardly. ‘How does THAT feel?’ I asked, and he admitted it felt wonderful and how he would like more of that feeling. I asked ‘What did you do differently on that day?’ and we then explored the different circumstances between why some days, some meetings some conversations he felt ‘in the zone and others he felt wrong as soon as he walked into the room.

Jimmy was discovering a pattern that when he was rested (often he had exercised), had prepared for the meeting/conversation thoroughly, and in short was ‘in a happy, positive, bold mindset’. I acknowledged how he was discovering some realities that he was not aware of previously. I asked, ‘What else?’ and he continued to correlate emotions, preparation, boldness, and his general mindset with his success or not on the day. Jimmy was getting a handle on his reality and learning that for a large part he was in control of his reality and success. We closed the session at this point and I encouraged Jimmy to continue to reflect on his current reality, as next if he was ready, we could move to the next phase which was to look at his options of changing how he avoids his Impostor Syndrome and also be aware of it at moments when he is not fully prepared to deal with a tough conversation or situation.

Sessions 3&4 – Exploring Options and a Working Plan

Sessions 3&4 were similar in content, and both opened again with a recap, reestablishing what Jimmy was looking to achieve against his current reality. We worked in the same manner of 80/20 speaking, my active listening and asking open-ended questions, coaching Jimmy and not the story. We arrived at a set of guidance that Jimmy wrote up for himself and added to his notebook on the first page to describe how we would engage in the future and what the new outcomes would be They included words such as ‘Bold’, ‘Prepared’, ‘Physically and Mentally Relaxed, Optimistic’. This contrasted with how Jimmy had been to meetings before: ‘nervous, unprepared, avoiding conflict, wanting to escape’. We talked about what supporting resources and structures he would have to help him, as well as removing unhelpful ones. And we talked about how Jimmy would hold himself accountable. I also suggested a Victory Journal, where every time he had a positive experience, he would capture it, no matter how large or small and he could refer to it when he was feeling low or needed some reassurance.

As the session ended Jimmy said he felt equipped to take on the challenges ahead. That he understood how he must avoid or at least interrupt the old destructive cycle of seeking perfection, of not going credit to himself, of punishing himself if he was not always the smartest guy in the room with the smartest comments. We stood up, shook hands and I wished him well.

2020 – Follow Up

I kept in touch with Jimmy sporadically over these 2 years. He said his awareness of the syndrome and that he was empowered to do something about it would be with him in every meeting and conversation for some time after that. He had moved the dial to 6 with fluctuations between 3 and 9. He said he is never fully able to ignore the impostor syndrome, that it is always there and so he has to constantly work and stay strong to keep it at bay. He continues to rise in the organization, meets larger challenges, and interacts with ever more senior, qualified, successful, intelligent people. He discusses it more openly with others, and in late 2019 he gave a lecture to his functional team (90 people) on what it is, how common it is and how it can be overcome. He wanted to help others by showing his vulnerability, and he also felt teaching and socializing were helpful to himself too.

Jimmy’s journey continues.

Reflections on This Case from My Impostor Syndrome

- Who Are the Main Players in This Case Study

The main player, in this case, was Jimmy (see Introducing Jimmy)

- What Is the Core Problem or Challenge to Which You Applied Your Coaching Skills To?

As the case study has captured, although Jimmy diagnosed the syndrome by himself, the core problem was how to manage/reduce it. Jimmy needed more than just a diagnosis, but a structured way of self-awareness, discovery, solution-oriented actions, and emotional shifts to take confident steps and ownership of a plan of action that would bring him to his goal.

- What Specific Coaching Skills or Approach Did You Use in This Case?

I used the GROW model as it is simple, robust, and effective. As we found in Discovery, Jimmy wanted to follow a set path with clear steps as this suited very much his way of working. In addition to that, the requisite skills of setting the coaching agreement, active listening, powerful questioning to create self-awareness of the goals, reality, and options/actions Jimmy can own and take were all required to bring Jimmy forward in his journey of overcoming the syndrome

- Explain Your Process in Detail

- What Were the Results of Your Process? Was Your Coaching/Program Effective?

Yes, it was effective, but within the coaching relationship up to the point of awareness, the discovery of reality, looking at the options Jimmy had at his disposal, and helping Jimmy crate a plan of action. The upper limit of effectiveness was always going to be equipping Jimmy with the capability of developing his tools and techniques to deal with good days and bad days that came after our formal relationship ended.

- If You Could Approach This Problem Again, What Would You Do Differently?

I would have liked to agree on a 3 month or 6 months check to help Jimmy with his newfound knowledge. At least for Jimmy to write a diary of what came next, what he learned from each event, and what he would then do differently. My learning from this is that the syndrome may never be fully conquered all the time but can be managed and controlled most of the time.

7. What Are the Top 3 Things You Learned From This Experience?

- That while we become emotionally involved in the client and their story, we must let it go and move on

- That every client is different and should be treated as an individual. There is not a manual for imposter syndrome that cures it for everyone, though some generalities do apply to most sufferers (research it, discover when it manifests and when it does not, talk about it, learn from each event, remind yourself to benchmark the external reality of your success

- That the client must discover and solve their way forward. The coach is merely the catalyst.

References

Clance PR, Imes, S. The Imposter Phenomenon in High Achieving Women: Dynamics and Therapeutic Intervention (1978). Psychotherapy Theory, Research and Practice Volume 15, #3

Scientific American

Merriam-Webster, (Merriam-webster.com)

Clance, P.R. The impostor phenomenon: Overcoming the fear that haunts your success Atlanta: Peachtree Publishers.

Sakulku, J. & Alexander, J. The imposter phenomenon. International Journal of Behavioral Science

Imposter Syndrome. BBC Radio.

The Imposter Syndrome. The School of Life.