Research Paper By Stacey Wallaberger

(Retail Coach, SWITZERLAND)

We have all made journeys in our lives. Sometimes we feel we are developing and moving forwards, and at other times it feels like we are retreating. This article looks at the effect of allowing fear and shame to rule us, such that instead of transforming from a caterpillar into a butterfly we move in the opposite direction and end up armoring ourselves like a pupa. This is what can happen when we feel the need to disguise our shame and vulnerability and shield ourselves from the world. We cover ourselves with impenetrable armor lest anyone discover how we really feel inside. But what was it that made us so vulnerable, insecure and fearful? And why such fear and shame?

Occasionally having doubts about who we really are must surely be a universal experience. We often see it as people acting in a manner that belies a lack of self-confidence and worthiness. At its worst it can lead to a feeling of paralysis where we know there is something more in us but are prevented by fear from taking the required steps to finding it. Ironically, the fact that so many of us have experienced this is actually good news. We are not alone. As humans, we are not isolated islands and nearly all of us will have felt these feelings at least once during our lives – many of us, much more frequently – I for one.

Let me to introduce you to myself. If, indeed as I have done, you asked my fellow peers, friends and family how they would describe me, the answer would be, ‘outgoing, super confidant, well balanced, articulate – a practiced orator’. But then if you asked me how honoured I felt to be described in this manner and I was feeling bold and honest enough to answer you truthfully, a very different picture would emerge. I would be forced to reveal that deep down inside I often feel like an impostor. That I fight demons who whisper in my ear how unworthy I am. That no matter how perfect I appear to be, no matter what admiring comments I receive, they know the true cost to me of maintaining my public facade.

There is of course a me that is a practiced orator who appears in public full of confidence and can speak to a crowd of any size. Meanwhile, there is another me that, for the sake of illustration, struggles to meet my graduation requirements and keeps putting the chore of writing my thesis off until it has become a sword of Damocles hanging over my head! The strange thing is that having studied my subject and read and re-read all the right books, I have it all planned out and know what my theme will be. But meanwhile those chattering inner voices continue to judge me, causing me to leave my writing chair and distract myself. How dare I believe I have the ability to write on such a subject, especially one that exposes my torments, indeed, my tormentors! And this goes on day after day as each new deadline slips past.

As a coach it has been very helpful to explore deep inside myself with the help of my own coach. This journey of discovery has enabled me to identify my most inner beliefs. But before examining these it will be helpful to explain a little about my background…

My mother tongue is English. But having lived in Switzerland for many years, I have learnt to speak German fluently. The result of my becoming bi-lingual has had some extraordinary and unexpected side effects. For example as my fluency in German has increased, there has been a corresponding decline in the use of my English, that seems to have occurred on an entirely sub-conscious level. Surely the words that were once so familiar and in daily use cannot have simply deleted themselves from my brain? Or is it that they have just been parked and temporarily forgotten in some other part of the brain, ready to be rolled out for use at some future time? All I know is that it has taken a supreme effort on my part to construct what you now so kindly read…

I wonder if my perfectionism has not been a useful tool for disguising what I really believe deep down. I present to you my random anxieties.

a) My fear of submitting an article of little or no value

b) My fear of being unable to use the right vocabulary to express myself

c) My shame that I may not succeed

d) My shame as my inadequacies are exposed to the outside world

e) Even more shame at my supposed lack of writing skills

f) My vulnerability in admitting that it was a real challenge

g) My vulnerability, in exposing my lack of inner self-worth

h) My vulnerability, offering my fragile underbelly to the outside world

j) More vulnerability since others may see me as a weak person

k) And worst of all my judgement of myself by myself

So it would seem that I have three deep emotions or beliefs that are stopping ‘me’ from moving on: Fear, Shame and Vulnerability. All three resonate with so much negativity…or do they?

In her book, Feel the Fear and Do it Anyway, author Susan Jeffers argues that fear can actually be a driving factor towards change. She postulates that without fear we cannot develop and grow. Indeed she urges us to look at fear and see what it can do to drive change in our inner selves, and to become more positive.

The author talks about fear emerging on three levels: Level 1 fears are more situation orientated, things that happen in our lives, for example, aging, loss of financial security and natural disasters. Then there are those Level 2 fears that require action on our part like making decisions, going back to school and making mistakes. Levels don’t really matter though because to quote her,

If you knew you could handle anything that came your way, what would you possibly have to fear?” And the answer of course is, “Nothing”. (Page 13)

But still the question remains, why does fear paralyse some of us into inaction?

Regardless of how we live our lives there will always sometimes be an element of fear, and it can be argued that without fear we cannot grow since growth involves taking risks. If we spend our lives waiting for the right moment, or for the fear to go away, we will wait for a very long time, maybe forever. The only way to lose fear is to confront it and face the challenge, as I have done in writing this article. In so doing I observe that there is a state of the ‘before’ and ‘after’ the taking of the action. ‘Before’ is where the fearful stumbling blocks may be found, and in ‘after’ can be found that feeling of achievement when the fear has been addressed, thus largely disappearing or at least substantially reducing.

It seems that each time we confront a fear and find a new way to deal with it, it lessens. A most important thing to keep in mind is that although on some level we are perhaps unique, on a human level of emotions we almost certainly are not. As we find some new way to deal with a fear, others all around us are doing the same thing with their own fears, all the time.

Think of the large number of entrepreneurs there are in the world. We usually end up hearing about the super successful ones, but how come they succeeded where all the others failed? What we wonder, was the secret of their success? Of one simple thing we can be certain. They all faced their fears and failed, possibly many times before the great breakthrough arrived. We see the same in dancers who fall hundreds of times while training in their careers, often facing and sustaining serious injury before the perfection we finally see on stage. Even then there’s no guarantee they will not fall again.

Pushing through fear is far more motivating than being stuck with a feeling of helplessness. Much depends on how each individual perceives their fear. Some are able to adopt a position of strength and power and see it as a challenge to be overcome, something exciting even or something deserving of strong action at any rate. Whereas in some it induces a feeling of helplessness that debilitates; in others it can cause depression, itself a kind of paralysis.

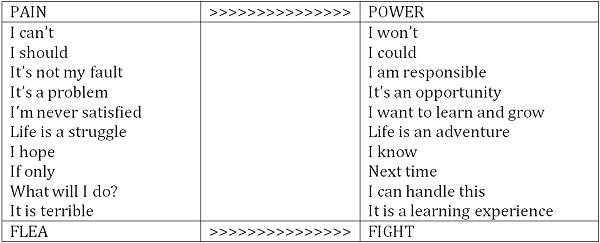

Susan Jeffers describes this concept of choosing how to see fear in her Pain to Power vocabulary (page 37). She suggests you can either stay stuck, or change your perception and move from weakness to a position of strength.

In my case I was fortunately aware of possibility, which after all is what coaching is all about. I stood and addressed my fear, choosing to be a hero rather than a victim. I simply refused to listen any longer to the judgmental chatterbox of my mind, and claimed responsibility over my life thus moving me from pain to a position of power.

In my case I was fortunately aware of possibility, which after all is what coaching is all about. I stood and addressed my fear, choosing to be a hero rather than a victim. I simply refused to listen any longer to the judgmental chatterbox of my mind, and claimed responsibility over my life thus moving me from pain to a position of power.

Another example of fear is illustrated by the necessity of writing this piece, since it is an ICA graduation requirement. It involves exposing oneself with the suspicion that ‘they’ have high expectations of you that you might not be able to fulfill. It could even be seen as a really frightening experience, since on one level the writer is dependent on others for their career survival. In such a situation and perspective the writer is constantly confronted with self-doubt. Will my work be good enough? Will ‘they’ understand what I am trying to express? Does the piece bring value to the reader?

Such an example suggests that if we fear, we cannot give properly of ourselves as self-doubt paralyses us and we start to close down to protect ourselves, just like the crystallized pupa that the caterpillar entraps itself in – nothing ventured, nothing put at risk. So in order to address this fear the best way seems to be to understand that we have to give of ourselves without ulterior expectations. To surrender and offer our thoughts whole heartedly, knowing we are giving of our best and giving it away freely without thought of personal gain, and what’s more enjoying the creative act feeling of just doing it. Susan Jeffers puts it like this.

When we give from a place of love, rather than a place of expectation, more usually comes back to us, than we could ever have imagined.

Brené Brown is a research professor at the University of Houston, who has devoted more than 13 years to studying Shame and Vulnerability. She is one of my ‘go to’ people when ‘me’ is having a ‘small breakdown’. She has published several books and papers and many of my ideas are from, “Daring Greatly”, “Listening to Shame” and “The Power of Vulnerability”, the latter two were presented as Ted talks.

Shame represents those gremlins of our inner self, the debilitating chatterbox that says, ‘You’re not good enough, or smart enough’. Then a voice asks, ‘who do you think you are anyway?’ At this point one needs to stop and ask who is actually generating this negative critique? And of course 99% of it comes from our own inner self-talk. It is like walking in the swampland of your soul and as Brené says, ‘put on your galoshes and face the music’. Despite our many privileges we are often paralysed with shame. Shame, being a mixture of fear and vulnerability.

Shame should not however be confused with guilt. Shame is focused on oneself vs. guilt that is focused on behaviour. For example shame says, ‘you are bad.’ Guilt on the other hand whispers, ‘you did something bad. Be sorry you made a mistake.’ Shame leads to addiction, depression and in some cases suicide, if not addressed.

Although shame feels somewhat the same in both genders, there is a definite difference between male and female manifestations. Females feel that they have to do it all and everything perfectly, never letting on that deep down they are sweating inside. They have unattainable conflicting expectations as to who they are supposed to be. Sad to say, this is like wearing a straight jacket of shame. Women often address manifestations of shame by provoking others with criticism.

Men do not tend to have conflicting expectations about themselves. Their main issue is not to be perceived as weak. Men react to being criticized for being inadequate, either by shutting down or coming back in anger.

Shame is the fear of disconnection with our fellow beings. It thrives on secrecy, silence and judgment. How often have we been in situations where we receive positive feedback but there is just one tiny suggestion of how you we might improve? And what does our mind actually hear? Why, only the small suggestion that is seen as negative, of course! Somehow we have to learn to lean into discomfort.

Theodore Roosevelt during his ‘Men in the Arena’ speech said the following:

It is not the critic who counts; not the man who points out how the strong man stumbles, or where the doer of deeds could have done them better. The credit belongs to the man who is actually in the arena, whose face is marred by dust and sweat and blood; who strives valiantly; who errs, who comes short again and again, because there is no effort without error and shortcoming; but who does actually strive to do the deeds; who knows great enthusiasms, the great devotions; who spends himself in a worthy cause; who at the best knows in the end the triumph of high achievement, and who at the worst, if he fails, at least fails while daring greatly, so that his place shall never be with those cold and timid souls who neither know victory nor defeat.

In order to be a man in the arena, one has to dare greatly – and vulnerability is the driver. That vulnerability is a weakness is one of the biggest myths, for to be vulnerable takes great courage. To be vulnerable is to be seen as we often and honestly actually are. In the business world, innovation, creativity and change are part of the daily jargon. Without the risk of being seen as vulnerable none of the above could take place, as in vulnerability is found the crucible of invention, the creation of something that was not there before.

In the years Brené has studied vulnerability she has observed the common traits of people who are prepared to address vulnerability and still stay connected with their fellow humans. Surprisingly such people often enough have far better connectivity than those who do not embrace it.

Struggling with vulnerability creates its own patterns:

True vulnerability is allowing ourselves be seen. Truly, deeply seen. It is in loving with our whole hearts, even though there is no guarantee our love will be reciprocated. It is practicing gratitude and joy rather than making everything into a catastrophe. It is to believe you are enough. It is to be silent and stop screaming inside and start listening to others. It is being kinder to ourselves.

We have to make that long journey from, ‘what will people think?’ to ‘I am enough’. That journey begins with shame, resilience, self-compassion and owning our stories. (Daring Greatly; B Brown page 131).

How do we come to own our own stories? It is by “Feeling the fear and doing it anyway”. Intuitively we are aware of our insecurities but not always willing to address them. By wanting to be seen and acknowledging the need to emerge like a butterfly out of the pupa, we cannot always take that journey alone. My being able to write this article was through admitting my need for help with my coach.

During my long journey of discovery I had to overcome my fear of being honest with myself and learn to trust my coach enough to have him champion me and help me to confront my fear, shame and vulnerability in a non-judgmental way. The environment of confidentiality was like being in that pupa. There was I, metaphorically wrapped in the fetal position, and by unraveling one thread of myself at a time I slowly moved towards wholeheartedly exposing my shame and vulnerability. Finally, I emerged like a butterfly, and what a beautiful, grateful me has emerged. More willing to take a chance and fail if necessary, but knowing I have taken the first step. And I have even written this article!

Lastly I would like to leave you with the quote from the Velveteen Rabbit by

Margery Williams:

“Real isn’t how you are made,’ said the Skin Horse. ‘It’s a thing that happens to you. When a child loves you for a long, long time, not just to play with, but REALLY loves you, then you become Real.’

‘Does it hurt?’ asked the Rabbit.

‘Sometimes,’ said the Skin Horse, for he was always truthful. ‘When you are Real you don’t mind being hurt.’

‘Does it happen all at once, like being wound up,’ he asked, ‘or bit by bit?’

‘It doesn’t happen all at once,’ said the Skin Horse. ‘You become. It takes a long time. That’s why it doesn’t happen often to people who break easily, or have sharp edges, or who have to be carefully kept. Generally, by the time you are Real, most of your hair has been loved off, and your eyes drop out and you get loose in the joints and very shabby. But these things don’t matter at all, because once you are Real, you can’t be ugly, except to people who don’t understand.

References

Feel the Fear and do it anyway – Susan Jeffers ISBN 9780091907075

Daring Greatly – Brené Brown ISBN 978-1-592-40733-0

com – Brené Brown, Listening to Shame

com – Brené Brown, The Power of Vulnerability