A Research Paper By Ruth Kwakwa, Young Adults Coach, GHANA

Coaching in Ghana Societies Steeped Tradition

Here in Ghana, many of my conversations with teens and young adults who are making big decisions around schooling, career, and life, inevitably bump into stumbling blocks that have to do with African cultural traditions. Coaching has tremendous potential for taking clients beyond obstacles, but I believe that navigating through hard-wired traditions requires coaches to be particularly attuned to the nuances and sensitivities that traditions present. I am sharing some of my observations and asking questions in the hope that coaching will continue to make inroads and be fully embraced in traditional countries like Ghana that are relatively unfamiliar with coaching, and yet are bullish on growth and development along modern, or “Western” lines.

Our 25-year-old cousin Charles entered the living room from the sweltering garden in Ghana, where twenty people, a mix of men and women, most of whom he didn’t know, were already sitting in a circle laughing and swapping stories. Charles instantly recognized a long-lost friend, Fred, sitting to the immediate left of the doorway, within arms-length. However, instead of reaching out to his friend Fred, Charles immediately veered right, away from Fred, rudely it seemed (to the untrained eye). Then, one by one, from right to left, in an anti-clockwise direction, Charles shook the hand of every single person in the room with almost military precision, until he arrived at his friend Fred. At this point, Charles and Fred shook hands exuberantly and melted into hugs and shouts of excitement.

Why didn’t Charles simply embrace his friend Fred first, before shaking hands with everyone else? After all, Fred was the only person that Charles knew. Tradition. Tradition in Ghana says that people can only say hello with the requisite handshake, in an anti-clockwise direction, from right to left. Tradition would not allow Charles to say hello to Fred first, because Fred stood to their left of the room.

To explain how deeply this tradition runs, here’s another anecdote. As a nine-year-old boy, my husband Kofi lost his father tragically. In the depth of his grief, little Kofi entered his living room, where family and friends of his precious daddy were all sitting in a circle, mourning. Kofi started shaking hands in a clockwise direction. Instantly, people in the room berated and chastised him, despite his deep state of bewildered sadness. The elders forced him to switch his direction, shaking hands in an anti-clockwise direction instead. My husband has never forgotten that moment, and the power of tradition to correct, curb and limit behavior, even at a moment of peak grief and despair. Such is the depth of tradition. It stands firm unless there is a bold and deliberate desire to interrogate, tweak or disrupt it.

These semi-fictional and true respective anecdotes are a tiny blip in the cultural landscape of traditional Ghana. They help to portray how deeply rooted traditions are in Ghana, my adopted home, where I am starting my coaching practice. Tradition, on the one hand, is laden with rules, and “shoulds” and “musts.”While coaching, on the other hand, pushes past limits. Traditional rules often defy the very universe of possibility that coaching is meant to inspire. As such, Ghana presents many opportunities for coaching. So, how can we ensure that we effectively introduce coaching as a means of getting unstuck and that it maximizes its impact in Ghana and other traditional societies?

Coaching as an Emerging Field in Traditional Ghana

I moved to Ghana after living in a wide range of communities since I was a teenager. Over 30 years and many moves, my enduring question ever since leaving my hometown in Jamaica to spend a high school year in Spain, has been about how cultures respond to ideas imported from relatively “more modern”/“Western” countries. For example, how does modern medicine infuse itself with traditional or indigenous medicine to make people healthier? Or how do modern business practices take hold in countries that thrive on a tradition of generational family businesses? Or how do Western “mainstream” Judeo-Christian weddings complement traditional weddings in African countries? How do we get old and innovative ideas to co-exist while leaving people better off for having merged the two? How do we translate words and concepts into other languages for equal impact? These have been some of my enduring questions, and so I go into coaching as an emerging field in Ghana with this in mind. How can transformational coaching take root in a traditional country that has its own system for resolving issues and promoting personal growth? How do we ensure that Ghanaians benefit fully from the power of coaching? I am optimistic about finding effective ways to coach here, even while acknowledging the positive and often beautiful role that tradition plays in Ghana.

How Tradition Frames Society

Tradition shows up in our daily lives more often than we realize. It shows up in conversations, in how we treat one another, and in the expectations that we hold for people. It slides in quietly when we say “yes” or “no,” and when we pause thoughtfully to make go and no-go decisions. Tradition sometimes shows up as a hierarchy, and determines the “pecking order,” suggesting who has more power, voice, and choice, and who has less. In Ghana and other countries, there is a traditional hierarchy around age, wealth, leadership, gender, religion, marital status, education, profession, race and/or ethnicity, and other forms of status, among other areas.

Traditions make life easy for us in many situations. They hold our hand and guide us when we struggle to make decisions alone and provide an easy answer to default to. “That’s just the way it is” makes for a quick response when we don’t have time or energy for reflection, and it is shorthand for saying “that’s how it has been done traditionally.” Many of us live with what I call “tradition by default,” the baseline for our everyday, unquestioned behavior, to varying degrees. We stick to many traditions believing that they fortify our countries and communities and that societies will crumble if too many traditions are tampered with.

My Coaching Focus, the “Twenty-Plenties”, and How Tradition Occurs for Them

My previous work in a university put me squarely in my happy space with young adults and solidified my desire to collaborate with people on the cusp of big decisions that set the foundation for their lives. My coaching will continue to focus on who I call the “Twenty-Plenties”: That is, older teens, and young adults in their twenties, who are beginning to navigate their promising adult years, filled with critical path-setting and dream-launching choices.

I run into “tradition by default” quite frequently with young adults. In a classic advisory scenario, while working on career and life strategies, students may express disappointment about missed opportunities, and a sense of longing for a field that they think they will enjoy or have a talent for. When I ask about what gets in their way, students often shrug and frown sadly, and say “I can’t. That’s the way it is”, or “I can’t. That’s the African way”. They say they aren’t allowed to pursue those interests, because, echoing their parents or other elders, “there are certain things that we can’t do”. By saying this they are implying that tradition does not allow them to question or debate their parents’ educational choices for them, or, that they aren’t allowed to choose certain things, because of the traditional expectations for their lives (as in the case of the example, of girls wanting to do engineering). What is clear, is that tradition, sometimes heaped on in multiple layers, stands in the way of choice and possibility for teens and young adults repeatedly. The shrug of the shoulders, coupled with a wistful look, is a common thread running through these conversations. The shrug, the tell-tale sign of resignation, epitomizes the amount of time that students spend wondering if their lives could be different and whether change is even worth considering. In this case, it leads students to default to the tradition of their parents. Marion Franklin calls what I see in students “ambivalence”, where “people get caught up in deciding” and points out how much valuable time and energy is spent deliberating around decisions. (Franklin 2019, p 107-8)

Traditions have a way of showing up in key life milestones. Such as puberty, first relationships, leaving high school, first jobs and salaries, gender-related moments (Ghana is extremely rigid about traditional gender rules), religious decisions, and marriage. Many issues around these rites peak in their 20s. And while traditional values may be a guiding force, the limiting beliefs that traditions may generate over time often prevent young adults from exploring alternatives and acting whenever they get stuck. Therefore, I believe that coaching stands to have tremendous value and impact on the Twenty-Plenties.

Why Don’t “Twenty-Plenties” Take the Initiative to Step Away From Tradition?

Many students show tremendous fear about stepping outside tradition when they get stuck. In peer-sensitive Ghana, young people constantly speak about doing everything in their power to avoid being the object of envy, isolation, sabotage, insults, and gossip. Students know that the consequence of stepping outside tradition can be swift and hurtful, and they spend a great deal of time worrying about what their friends and family would say if they stepped out, even if their parents allowed them to.

One of the consequences that teens fear, is being called “Too known,” which is an insult that is hurled in a playful, teasing, yet disparaging manner with ugly undertones, even at children under the age of ten. (Usage: “Ruth is too known”). The expression is colloquial Ghanaian English and is one of the most subtly insidious insults that is directed at people who try to step outside of tradition, or who push the boundaries of knowledge and ideas. The fact that there is even an insulting expression that society has coined to reign in people’s ideas, speaks volumes about the reverence with which status quo and tradition are held by the wider community. Describing someone as “Too known” is a debilitating and socially isolating gesture, which attempts to mold people and their voices into a particular way of thinking and being over time. Many people have painful childhood and teenage memories of being described as “Too known,” and consequently, seek to “stay in their lane” and play by the rules, instead of venturing out to try something new, even as mature adults.

Because people start being sensitive to this label so early, its power to suppress ideas and voice accumulates, and eventually weaves its way into classrooms, lecture halls, and workplaces, and into simple yet powerful activities like brainstorming, ideation, concept development, and strategy building. For example, in brainstorming sessions that invite students to “think outside the box, cast your net wide, and bring all ideas back to the group,” it is not unusual for the room to fall silent. Why? Because many harbor a latent fear of speaking out with innovative or quirky thinking, out of fear of being labeled “Too known” by peers. Often students restrict themselves to ideas that are safely within the confines of the traditional “box.”In other instances, people in the session may respond based on how they think they will be perceived by others in the session, perhaps based on a traditional hierarchy: For example, young women may be slow to speak up (gender hierarchy), or people may be slow to speak ahead of friends and colleagues who are as little as a year older than them (age hierarchy). Therefore, even a simple student ideation exercise can easily be suppressed by tradition, which serves as a “gatekeeper of creative solutions’ in such cases. The closest modern/” Western” equivalent of this form of social control would be “cancel culture,” which LythcottHaims says causes young people to silence themselves out of fear of making a big mistake. (2019,p. 92). The effect of being labeled “Too known” and being “canceled” have the same effect on people’s willingness to test ideas and express themselves.

Fear and the societal pressure that young adults feel in relation to breaking away from tradition are prevalent in Ghana. How then should we introduce coaching that is expansive and provides choice, possibilities, and boundless scope for creativity in our lives, knowing that students are so fearful of the consequences of stepping outside tradition?

Things to Consider as We Coach

The ICA coaching approach already provides tools that we can apply in our work with clients who are steeped in tradition. However, mindfulness and sensitivity to tradition are key. When we partner with clients, we need to suspend judgment, leaving space for them to broaden their insight, and peel back the fear that is associated with walking away from, or tweaking tradition. Here are some ideas that I have about partnering with such clients, based on what I have experienced, and what I am learning through coaching.

- Provide empathy for clients who showFEAR about reconsidering tradition.

- Listen out for the fear that links itself to the need to belong, that Maslow speaks of in his “hierarchy of needs.”(Maslow, 1943)Fear about breaking through and pushing past tradition often has to do with acceptance by the family or community unit(s), that the client considers themself a part of. “Will I be true to my ethnic tribe/clan/church, and still fit in, if I go against tradition?” is the question that many ask.

- Give the client an opportunity to express how the tradition feels to them: Traditions seldom evoke ‘neutral’ feelings, and even when the end results of an observed tradition feel negative, it is possible for the tradition itself to feel positive, and vice versa. Give clients room to explore this.

- Knowing that tradition often feels good and safe to some clients, accept that the shift may take a while to emerge, and move at their pace. As Marion Franklin quotes Henry Cloud, “We change our behavior when the pain of staying the same becomes greater than the pain of changing. Consequences give us the pain that motivates us to change.”

For as long as the client is pain-free and comfortable with what tradition does for them, the true shift may not occur. (Franklin, 2019, p. 154). As Franklin goes on to say “There’s a reason your client is holding on to an idea that prevents forward moment, otherwise they would have resolved it themselves and you wouldn’t be having a coaching conversation. As a masterful coach, you can help your client invent new interpretations of their perceptions and connect dots that may not be obvious to them.” (Franklin, 2019, p.155). Tradition will always feel good for some people. That’s why some people never leave their community, town, city, or country for their entire life. Tradition puts people at ease.

- Show CURIOSITY for feelings and thoughts that clients may link to tradition.

It is critical to walk with the client as they tease their perspectives and make the link to tradition for themselves. This calls for curiosity, as the client themselves may be unpacking something they’ve always known by default but has never once interrogated. Most often, clients assume that a coach from the same context is in the same understanding of the culture as the client, and so tend not to explain themselves. Therefore, the coach needs to ask questions as though they have little or no knowledge of the tradition and allow the client to fill the space.

- Allow the client to explore the origins of their thoughts, so that they can go through the process of noticing tradition. Without being caught up in the story, be open to a “historic” or “academic” discussion about a tradition, allowing the client to recognize that traditions all arise out of a particular need at a particular moment in time, to solve a particular problem that is peculiar to a certain situation. Exploring a tradition historically and going back to its origins, allows us to reframe it, and make it more useful and dynamic. It might allow the tradition to appear as something more useful for the past, for a historic situation, than it is now. In effect, we’d be re-framing the tradition (Franklin, 2019, p.166). “What is truth?” might be an interesting question to ask about any tradition that keeps showing up.

- Invite the client to explore the distinction between tradition and values. Sometimes when the client speaks, they will blur the line between value and tradition. If so, present the client with the opportunity to tease it out, separating one from another with specific examples. For example, in Ghana, carrying an elder’s bag speaks to a non-negotiable value-laden tradition. However, a second-year university student cleaning the shoes of a senior in university (assumed to be another form of serving an elder) may be a modern-day university tradition that has formed and deviated from the original traditional value. Perhaps a good question to explore as a client exercise would be “Does tradition trump value, or does value trump tradition? What is the relationship between the two?”Having a client make the distinction between values and tradition would be very impactful.

- Create an exercise that allows the client to imagine themselves outside the tradition, looking in. This may allow them to develop a more neutral approach to the tradition, to be able to discuss it dispassionately, and consider more possibilities around a troubling issue. Here’s an example of someone who shifted his thinking after looking at his tradition neutrally, in a (non-coaching)situation. (I have changed the names for privacy).

Ghanaian Kwame wanted to marry his long-time love American Anne, for whom elaborate cooking was not a priority. However, Kwame came from a tradition in which extensive and intensive food preparation and copious food practices for households were an absolute must and the sole domain of women. They intended to relocate to Ghana after getting married. Because this traditional requirement peaked just prior to the would-be engagement, and because it meant so much to Kwame, they finally decided to break off the 6-year relationship. Neither of them could see Anne playing the traditional role around cooking. They were both devastated and heartbroken.

A few months later, however, Kwame looked more closely at the tradition through culturally agnostic eyes. In so doing, he realized that he wasn’t even a “foodie,” and didn’t care as deeply about food as many of his Ghanaian family and friends. He came to the realization that he was more committed to the relationship than to maintaining the food traditions. Revisiting and analyzing the tradition allowed him to open his mind to tweaking the traditional rules around food, and eventually get married to Anne.

Coaching is already well-poised as an “awareness-raiser” and so is able to help the client to interrogate the environment that contextualizes and frames traditions without delving into “the story.” Asking open-ended questions while suspending judgment and partnering with the client to observe themselves and their beliefs from a new perspective, are strong coaching techniques while considering the client in a traditional background. These will help to coach to make sustained inroads in traditional societies.

- Show RESPECT for tradition while creating alternatives and choices.

- Ensure that the client knows that they have absolute CHOICE, regardless of the notion that tradition is fixed and binding. This shows respect for the client as a person with agency and autonomy, who can make the best decision for themselves, after interrogating the benefits and costs of the options.

- Ask the client to imagine “what it would look like if…,” to have the client visualize what the best possible outcomes of a choice that pushes through tradition might be.

- Explore options within traditions. It is good in tradition. But because people often accept tradition in its entirety as a given, it becomes fixed in our heads as an all-or-nothing absolute and complete, lock-stock-and-barrel, binary matter. This means that we don’t often consider dissecting alternatives and components within the tradition. As coaches, we could invite clients to break down traditions into various components and explore what “tradition” could look like when the components are combined differently. In her book about adulting Lythcott-Haims, (2021, p. 86) cites an example of a teenage girl who was disallowed from attending her religious classes because she asked too many questions, implying disagreement. Ironically, the girl went on to study her religion on her own and found aspects of her religion that resonated even more strongly with her after doing so. So, “rejection” of one aspect of her tradition led to her embracing what for her became a more empowering option within her tradition, which contributed to her growth.

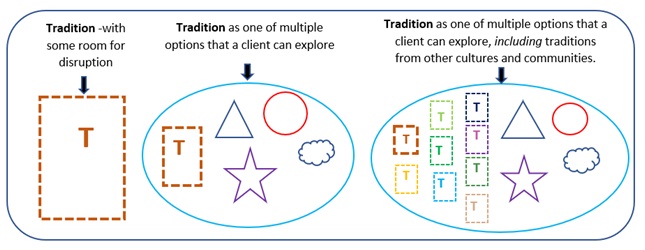

- Remind the client that their tradition is valid, and that adhering to their tradition “as is,” is among the choices that are available to them. Also let them know, that traditions from other cultures are also available to them as options for getting unstuck. After all, if the client considers that ALL traditions are up for grabs then aren’t others’ traditions also acceptable as a possibility for growth and self-expression? Transformational coaching almost suggests that ALL options are on the table, regardless of the origin of the particular option. The diagram shows how tradition can be honored as a potential option in transformational coaching.

I believe that for transformational coaching to take root in traditional societies, we need to think about the role that it plays in our clients’ lives. Tradition in and of itself is not bad per se. But when the client sees their tradition as the only viable way of being, gets stuck, and ceases to grow in response to the limitations, then we should consider the opportunity to empower them through coaching, and what successful coaching entails under the circumstance. This discussion is only the start of that consideration for me, and I hope it will grow as I partner with more Twenty-Plenty clients who are starting their beautiful adult journey. I believe that coaching can play a key role in transforming the way young people gain ownership and agency for their life decisions, and I look forward to seeing it breaking into spaces steeped in tradition, in powerful ways.

*“Twenty-Plenties” is a name that I have coined to express optimism and abundance about the years between the age of 20 and 30, plus a couple of years on both ends. I believe the twenties are some of the most exciting years of someone’s life, brimming with possibility.

References

Franklin, M. (2019). The Heart of Laser-Focused Coaching. A Revolutionary Approach to Masterful Coaching. Delaware: Thomas Noble Books.

Lythcott-Haims, J. (1921) Your Turn. How to be an Adult. New York: Henry Holt and Company.

Maslow, A. (1943). A Theory of Human Motivation. 1943