A Coaching Power Tool By Julia Paulsson Jandl, Relationship Coach, AUSTRIA

Rollercoaster vs. Taking Ownership

Brian, 34, and Katie, 35, have been in a relationship for the past two years. They moved in together one year ago. They keep having the same argument over and over. Katie is part of a women’s rugby team and likes to go out with her mates after training. She gets annoyed that Brian calls her multiple times when she is out. When she sees Brian’s number, she presses the mute button. Katie likes flirting. She sees it as innocent fun. Brian gets angry about this. When Katie is out, Brian paces up and down the living room. When Katie doesn’t take his calls, he starts sending a litany of text messages. Brian and Katie frequently fight about this dynamic, with Katie typically storming out of their apartment to sleep at her sister’s. Brian wants Katie to go out less and spend time with him instead, of cooking dinner or watching a movie. Katie thinks that Brian is controlling and clingy. Brian feels that Katie does not care about him. This argument is a recurrent issue in the relationship.

Steven, 42, and Kevin, 39, have been dating for one month. Steven is constantly thinking about Kevin, checking his phone every few minutes. He types a message to Kevin, deletes it again, types another one, and deletes it again. He finally sends a message. One hour later, still no response from Kevin. Steve finds himself increasingly worried. He wonders whether Kevin isn’t attracted to him or finds him boring. It is an inner struggle for Steve on whether to call or text or not. His thoughts are preoccupied with this thing he has going with Kevin, he feels antsy. When Keving first saw Steven, he felt instantly attracted, both physically and emotionally. Yet, a few weeks after the first date, he finds himself losing interest again. Around the same time when Kevin starts losing interest and finds himself withdrawing, Steven becomes quite ‘intense’. Kevin keeps wondering what’s wrong with him, whenever he meets someone who seems promising, it just takes a few weeks for him to lose interest. When will he meet ‘The One’?

Do you recognize yourself in any of the dynamics?

Attachment theory is an evidence-based account of intimate relationships, charting the reciprocity upon which an individual’s survival, developmental progress, and emotional flourishing depend (Holmes, 2015). Attachment theory was pioneered by Johan Bowlby and Mary Ainsworth. New-born babies’ attachment secures their survival as well as their social, emotional, and cognitive development. Yet attachment is not unique to infant-carer relationships (Main, Kaplan, & Cassidy, 1985). It is present in many forms of social relationships including romantic relationships, as well as the relationship with ourselves. Our attachment style(s) influence how we behave in these relationships.

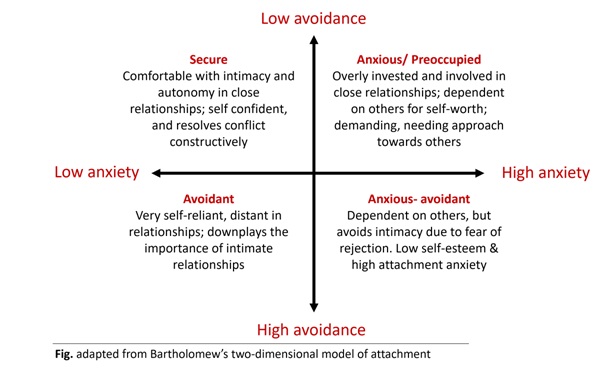

Research by Mary Ainsworth (1969) and subsequently Mary Main (1986), categorized attachment styles into secure and insecure attachment styles. Insecure attachment styles are subdivided into anxious, avoidant, and disorganized attachment styles. Overall, about half of the population are securely attached, 20 percent are anxious, 25 percent display an avoidant attachment style, and three to five percent are considered a combination of anxious and avoidant (Levine & Heller, 2019). People with a secure attachment style, typically are comfortable with intimacy and autonomy. Persons that are anxiously attached, or preoccupied with relationships seek intimacy while feeling a lot of insecurity around the relationship. Persons that are avoidant, tend to be uncomfortable with too much closeness and intimacy and are keen to maintain their independence and freedom in the relationship.

If you are curious about your own attachment style, try the fully validated adult attachment questionnaire on the website of Dr. Chris Fraley https://www.web-research-design.net/cgi-bin/crq/crq.pl

A few points are critical to note here:

- There is no ‘good’ or ‘bad’ attachment style. If you fall in the secure category, that is ok and it is equally ok if your default attachment style falls into the insecure category. However, understanding our attachment style and the science of adult attachment can help us in finding and maintaining love.

- There is plasticity to our attachment style, meaning that it can be modified. Knowing our specific attachment style can help you understand yourself better and allows you to shift your perspective on relationship dynamics.

- We may relate differently to different people. While you likely have one core attachment style, you may have different attachment styles with different people. I found it particularly helpful to think of our attachment style as a spectrum across which we can move, rather than a box we are stuck in.

Rollercoaster vs. Taking Ownership of Your Relationship Needs Power Tool

Rollercoaster

The dating pool disproportionately includes persons with anxious and avoidant attachment styles (Alan Graham, 2019). Persons with a secure attachment style, once settled in a relationship, take a long time to re-appear in the dating pool, if they return at all. Avoidants are in the dating pool more frequently and for longer periods of time. In addition, avoidants are unlikely to date another avoidant but are more likely to date persons with a different attachment style.

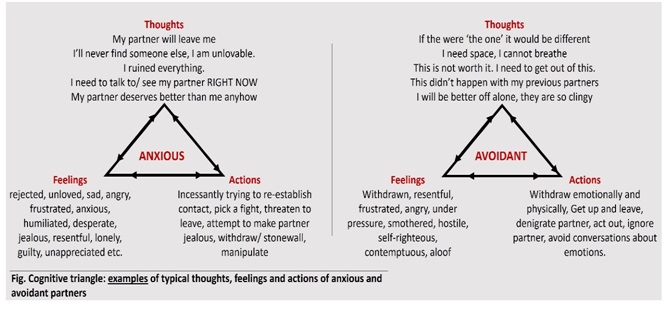

When two people have different needs for intimacy and closeness, their relationship is likely going to resemble a roller coaster ride rather than a stroll, hand in hand, through the amusement park. This is particularly pronounced in dynamics involving one partner with an anxious and another with an avoidant attachment style. While one partner craves intimacy, the other feels uncomfortable when things become too close. Both partners are exacerbating each other’s insecurities. This in turn reinforces the anxious partner’s insecurity and amplifies their anxious call for even more closeness, triggering the avoidant partner’s instinct to withdraw even further. The cognitive triangle, a key concept of Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) developed by Beck in the 1960s, demonstrates the interrelated nature of thoughts, feelings, and actions. It explains how our thoughts change the way we feel, which subsequently changes the way we act, which in turn impacts our thoughts. Without disruption, the process continues to repeat.

The anxious partner may think that their partner will leave and that they ruined the relationship. They may feel their self-worth dwindle; they may feel unlovable. They may start calling incessantly, pick a fight or try to manipulate their partner to connect with them. The avoidant may think that their partner is not ‘The One’, that they need space, that this is not worth it, and that they may be better off alone. They may feel resentful, misunderstood, smothered, contemptuous or self-righteous. The avoidant may stonewall, withdraw physically and emotionally, and avoid conversations about feelings. At the same time, avoidants are often less in touch with their emotions. They may feel the urge to get away, yet may not understand why. Rather than processing that they have a need for some personal space, they may think they are just no longer into their partner. Those are just examples of how the circle may play out.

‘When couples disagree about the degree of closeness and intimacy desired in a relationship, the issue eventually threatens to dominate all of their dialogue’ (Levine& Heller, 2019). This is called the “anxious-avoidant trap”, because like a trap, you fall into it with no awareness, and like a trap, once you’re caught it’s hard to break free (Levine& Heller, 2019). This perspective is disempowering and ultimately negatively impacts the relationship satisfaction of both partners.

So, what can you do when you are in a relationship where your intimacy needs clash?

Pull the Plug on the Rollercoaster and Take Ownership of Your Relationship Needs

As indicated above, attachment styles are constant but plastic or modifiable. We have the power to take control. We can pull the power plug of the roller coaster and take a step back and say: I see me and I see you.

Awareness of your attachment needs is the first step to owning them. Owning them means effectively communicating these relationship needs and being more intentional. If you are dating, this will help you identify whether your prospective partner may be able and willing to meet these needs. If you are in a new or long-term relationship, it will make it easier for your partner to meet your needs. It takes away the need for guesswork and helps your partner understand certain thoughts, feelings, and behaviors you may be having.

Instead of desperately seeking to establish a connection with your partner and engaging in protest behavior, let them know upfront that you need reassurance to feel secure in the relationship. Instead of storming out of the room, ghosting your partner, or lashing out when overwhelmed with emotion, let them know that you are committed to them, and that at the same time, you value some independent space, but that this does not change your feelings towards them. Know your triggers and catch yourself when you get triggered.

Be brave and take a risk making yourself vulnerable. Be honest about your feelings and focus on your needs when communicating. Be specific and use simple language to increase your chances of being understood. Communicate your needs without putting blame on your partner or criticizing them. And on your needs, no need to be apologetic about such fundamental human needs or feel ashamed.

Being so vulnerable and open is also an invitation to your partner to do the same. Owning and effectively communicating your own relationship needs, and understanding your partners’, has the power to transform your relationships or if you are in the dating pool, help you weed out the ‘Oh yes-es!’ from the ‘Maybe not-so.

References

Holmes, J. (2015). Attachment Theory in Clinical Practice: a Personal Account. British Journal of Psychotherapy. 31/2, p.208-228. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/bjp.12151(accessed on 08.11.2022)

Main, M., Kaplan, N., & Cassidy, J. (1985). Security in infancy, childhood, and adulthood: A move to the level of representation. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 50(1-2), 66–104. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2307/3333827 (accessed on 08.11.2022)

Ainsworth, M. D., & Wittig, B. A. (1969). Attachment and exploratory behavior of one-year-olds in a strange situation. In B. M. Foss (Ed.), Determinants of infant behavior (Vol. 4, pp. 113-136).

Main M., & Solomon J. (1986). Discovery of a new, insecure-disorganized/disorientedattachment pattern In Yogman M. & Brazelton T. B. (Eds.), Affective development in infancy (pp. 95–124). Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

Levine, A. & Heller, R. (2019). Attached - Are you anxious, avoidant, or Secure? How the science of adult attachment can help you find – and keep – love. 2nd edition. Bluebird.

Alan Graham, J. (2019) On Relationships: The Basics. Available at https://www.atlantacenterforcoupletherapy.com/realationaships-thebasics (accessed on 08.11.2022)