A Research Paper By Meaghan Sullivan, Performance Coach, UNITED STATES

What Is Acceptance and Commitment Coaching?

Acceptance and commitment coaching (ACC) originates from acceptance and commitment therapy, or ACT (pronounced like the word “act”). ACT is part of the third wave of behavior therapy, following the first wave, traditional behavioral therapy, and the second wave, cognitive behavioral therapy (Hayes et al., 2006). Unlike traditional behavioral therapy, which focuses only on changing behaviors and largely ignores the role that thoughts have on those behaviors, or cognitive behavioral therapy, which aims to change a person’s thoughts and behaviors, ACT addresses how we relate to our thoughts, without having to change them, and focuses on taking meaningful actions despite those thoughts being present (Hayes et al., 2013).

The role of an ACC coach is to present clients with the idea that it is not the presence of intrusive thoughts and feelings that disrupts life. Rather, the problem is how clients tend to respond to those internal events, by pushing them away, denying them, or avoiding them altogether (Hill & Oliver, 2019). ACT and ACC are grounded in a phenomenon called psychological flexibility, which is the ability to contact the present moment more fully and to either change or persist in a chosen behavior when doing so supports one’s values (Hayes et al., 2006). In other words, psychological flexibility is about acting by one’s values, despite the presence of unwanted or unhelpful thoughts or feelings. Ultimately, an ACC coach helps clients develop greater psychological flexibility.

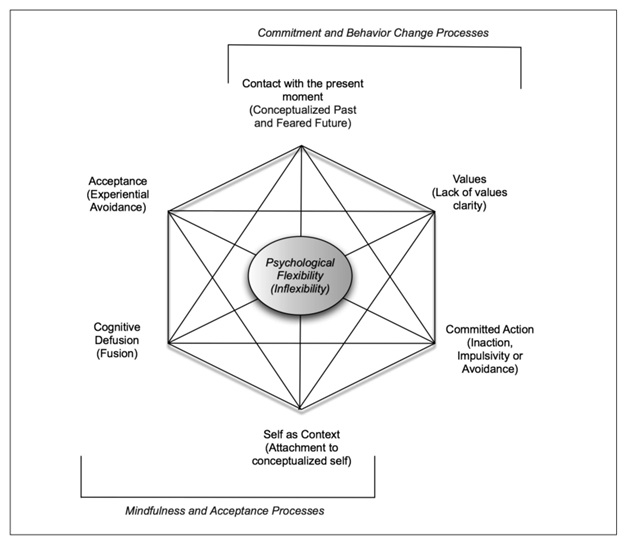

Psychological Flexibility & the Hexaflex

Psychological flexibility consists of six overlapping and interrelated processes that help individuals lead a more values-consistent lifestyle. The six processes are acceptance, cognitive defusion, being present, self-as-context, values, and committed action. The six processes combine to create the ACT Hexaflex (see Figure 1). Each of these processes has an opposite process that likewise promotes psychological inflexibility (Hayes et al., 2006), as indicated in parentheses in Figure 1.

- Acceptance is about actively embracing the presence of thoughts and feelings, regardless of their content. Critically, acceptance is not about accepting the message that thoughts and emotions send. Rather, it reflects an acknowledgment that unwanted or uncomfortable thoughts and feelings will inevitably arise when one is living a full life. Acceptance allows individuals to release themselves from the inner tug-of-war between their senses of self and their thoughts, perceive such internal events with curiosity and openness, and choose behaviors that ultimately align with their values.

The opposite of acceptance is experiential avoidance, which occurs when individuals attempt to change the form, frequency, or intensity of naturally occurring thoughts and emotions. While avoidance may provide short-term relief, it is not sustainable long-term. Habitual avoidance moves individuals further away from valued living, and it reinforces the idea that thoughts and emotions are the problems when the avoidant response itself is the real issue.

- Cognitive defusion occurs when individuals change how they interact with or relate to their internal experiences, rather than change the internal experiences themselves (e.g., choose different thoughts). Defusion creates a meaningful space between one’s sense of self and one’s thoughts, which enables one to detach from literal interpretations of thoughts and feelings and, instead, recognize each thought as being just that—a thought. In this defused space, clients are empowered to make more informed and values-driven choices.

The opposite of cognitive defusion is cognitive fusion, which arises when thinking interferes with psychological flexibility. That is, individuals, become fused with their thinking to such an extent that they believe their thoughts are true, even though they may not be. Moreover, fusion causes individuals to live in their heads rather than in the present moment, which leads to greater inflexibility, as their behaviors are driven by what the mind is saying, rather than by reality or personal values.

Common fusions include:

- Being fused with thoughts about the past or future (e.g., I’ve never been good enough, and I never will be.)

- Being fused with judgments about ourselves and others (e.g., I’m not cut out for this. People are so much better than I am.)

- Being fused with rules about how life should be (e.g., I shouldn’t have to try this hard.)

- Being fused with reasons for why things are the way they are (e.g., The reason I have never been in a meaningful relationship is that I’m unlovable.)

- Being present involves having ongoing and non-judgmental contact with the present moment and experiencing life’s events as they unfold. Being present means maintaining mindful awareness of when the mind unproductively wanders into the past or the future and then gently redirecting attention back to the present. Maintaining a presence voluntarily and flexibly and having increased awareness of internal thoughts and feelings promote less automatic, emotion-based reactions and inspire more meaningful, values-based responses.

The opposite of being present is having a loss of flexible contact with the present. Contexts that promote fusion and avoidance tend to remove individuals from the present, which results in their becoming wrapped up in the mind’s stories about the past or future. Often, these stories are laced with judgment and self-criticism, thereby fueling cognitive fusion and experiential avoidance. For example, a client may begin to ruminate about past failures, believe he or she is destined to fail again, and, as a result, the client avoids trying new things altogether.

- Self-as-context refers to viewing oneself as the place in which thoughts and emotions occur (i.e., in the mind), rather than as the content of those thoughts and feelings (i.e., the message). A helpful analogy is to think of the self as being akin to the sky that contains all the clouds, wind, and weather. Although the weather is constantly changing, the sky remains the same and is simply the location in which weather unfolds (Hill & Oliver, 2019). When individuals begin to observe themselves as being distinct from (i.e., being the location in which) thoughts and emotions unfold, it is easier to adopt an outsider’s perspective and hold these internal stories more lightly. The goal of self-as-context is not to abandon one’s self-stories but, instead, to become more flexible in one’s interpretations of and responses to them.

The opposite of self-as-context is self-as-content, in which individuals become attached to a conceptualized version of themselves. When attached to one’s conceptualized self, one may feel threatened by thoughts and feelings and view them as a set of rules that must be followed or truths to obey. Consequently, it becomes difficult to recognize the sense of self that notices and observes (i.e., the sky) as being distinct from one’s ever-changing internal experiences (i.e., the weather).

- Values are best interpreted as a direction to move in rather than a destination to reach. As such, values are different from goals because they have no endpoint. In addition, values are personally chosen ways of being and doing that reflect who one is and aspires to be. They serve as an anchor in turbulent times and, ideally, they guide individuals to take meaningful actions every day. The overall purpose of ACC is to increase clients’ abilities to persist in or change behaviors in service of their chosen values.

The opposite of values is a lack of values clarity. When unsure of what they value, individuals act not from a place of personal choice and meaning but a place of avoidance (e.g., to avoid looking bad), social compliance (e.g., to appease family or friends), or fusion (e.g., obeying the mind’s unhelpful rules). Ultimately, these behavioral choices lead to greater inflexibility and being further from what matters.

- Committed action involves the development of behavioral patterns that support one’s chosen values. It entails a willingness to experience unwanted or intrusive thoughts and emotions and to nonetheless engage in values-driven behaviors. Staying mindful and flexible in response to internal experiences is essential, as doing so increases one’s ability to stay connected to personal values. If values represent the direction in which one moves, then committed action is the mapping and commencement of the journey. Importantly, a successful journey is not achieved by reaching a destination. Instead, success is experienced every time one commits to and acts in service of his or her values.

The opposite of committed action is inaction, impulsivity, or avoidant persistence, each of which reflects an incapacity to engage in values-based behaviors. This is due to experiential avoidance, loss of contact with the present moment, and an attachment to the conceptualized self.

ACT Applied to Acceptance and Commitment Coaching (ACC)

Researchers have highlighted several benefits of applying ACT in the coaching context (i.e., ACC). Perhaps most importantly, ACC is evidence-based coaching, as it has a strong theoretical underpinning (i.e., psychological flexibility) that applies to various contexts in both clinical and non-clinical populations (Bond & Bunce, 2000; Flaxman & Bond, 2010; Hayes et al., 2011). Consequently, any ACT-based intervention can explore whether changes in client outcomes, such as performance, well-being, or goal attainment, resulted from a shift in psychological flexibility (Skews & Palmer, 2016). In addition, ACC uses mindfulness and acceptance processes to achieve improvements by focusing on decreasing emotional reactivity and accepting events as they occur (Cavanagh & Spence, 2013; Skews & Palmer, 2016). Such mindfulness methods have already been successfully used in occupational coaching (Hall, 2013) and sports psychology (Gardner & Moore, 2004).

What the Research Says

Over 200 randomized controlled trials examining the effectiveness of ACT on a variety of outcomes, such as work stress, anxiety, mood problems, and substance misuse, have shown it to be at least as effective as previously established protocols, like cognitive behavioral therapy (Hill & Oliver, 2019). Additionally, research has shown psychological flexibility to predict performance outcomes such as employee innovation, new skill learning, higher perceived job control, reduced absenteeism rates, general mental health, stress, burnout, and overall well-being (Hayes et al., 2006; Hill & Oliver, 2019). To date, only one ACC coaching intervention has been formally evaluated, and the findings showed significant effects on well-being, proactivity, self-efficacy, and goal achievement (Skews, 2018).

Acceptance and Commitment Coaching Has a Bright Future Ahead of It

Although research on ACC is in its infancy, ACC holds great promise for future clients in the coaching community, given its strong, evidence-based foundation. In today’s world of “positive vibes only” and the incessant pursuit of happiness—as though happiness were a tangible destination—ACC stands to liberate clients from these unrealistic standards by empowering them to co-exist with their thoughts, emotions, and self-stories, neutralize their influence, and actively choose to live by what matters most.

References

Bond, F. W. & Bunce, D. Mediators of change in emotion-focused and problem-focused worksite stress management interventions. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology

Cavanagh, M. J. & Spence, G. B. Mindfulness in coaching. The Wiley-Blackwell Handbook of the Psychology of Coaching and Mentoring

Flaxman, P. E. & Bond, F. W. A randomized worksite comparison of acceptance and commitment therapy and stress inoculation training. Behaviour Research and Therapy

Gardner, F. L., & Moore, Z. E. A mindfulness-acceptance-commitment-based approach to athletic performance enhancement: Theoretical considerations. Behavior Therapy

Hall, L. Mindful coaching: How mindfulness can transform coaching practice. London: Kogan Page.

Hayes, S. C., Levin, M. E., Plumb-Vilardaga, J., Villatte, J. L., & Pistorello, J. Acceptance and commitment therapy and contextual behavioral science: Examining the progress of a distinctive model of behavioral and cognitive therapy. Behavioral Therapy

Hayes, S. C., Luoma, J. B., Bond, F. W., Masuda, A., & Lillis, J. Acceptance and commitment therapy: Model, processes, and outcomes. Psychology Faculty Publications

Hayes, S. C., Villatte, M., Levin, M., & Hildebrandt, M. Open, aware, and active: Contextual approaches as an emerging trend in the behavioral and cognitive therapies. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology

Hill, J. & Oliver, J. Acceptance and commitment coaching: Distinctive features. Routledge.

Prevedini, A. B., Presti, G., Rabitti, El., Miselli, G., & Moderato, P. Acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT): The foundation of the therapeutic model and an overview of its contribution to the treatment of patients with chronic physical diseases. GiornaleItaliano di Medicina del Lavoro ed Ergonomia

Skews, R. A. Acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) informed coaching: Examining outcomes and mechanisms of change. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Goldsmiths, University of London, London, UK.

Skews, R. & Palmer, S. Acceptance and commitment coaching: Making the case for an ACT-based approach to coaching. Coaching Psychology International