A Coaching Power Tool By Isabelle Finger, Executive Coach, UNITED STATES

Embrace vs. Tolerate The Inconveniences Life Brings to Us

On a warm summer Sunday evening, Anna is turning the TV on. She has no precise idea what she is going to watch, she only wants to get her mind off the uncomfortable weight she feels in her belly. Anna jokes about this specific feeling and calls it her “back to work tummy”. Only recently, Anna learned that she is not the only one experiencing this sense of anxiety. There is even a name for it: “Sunday Scaries”[1]. For years, Anna has been trying to avoid them by numbing her mind at the end of the weekend. She has come to accept the Sunday anxiety as a normal part of her routine, as one of the inconveniences life brings to us, and that we need to endure without complaint as a responsible adults.

On that specific summer Sunday though, one question popped into Anna’s head: What if her Sunday scaries were telling her something about her life?

This powerful question was the start of a journey that would lead Anna to gain awareness about her underlying needs, to challenge her limiting beliefs, to face her emotions, to discover a stronger life purpose, and to act on the conditions of her life. Today, Anna is coming out of a transition period. As she started reflecting and creating the conditions to better thrive in her job, she noticed that such changes had consequences on her private life too. Anna tackled those challenges too and redesigned her life in a way that better reflects her dreams, values, and expectations at this period of her life. Sunday evenings are now dedicated to walks with her dog – enjoying the outdoors, the presence of the loving animal, and, last but not least, the absence of the Sunday scaries.

Anna’s story illustrates a metamorphosis that many of us would like to go through.

Tolerate – Lights and Shadows

At the beginning of the story, Anna is tolerating an uncomfortable situation. The verb “tolerate”, from the Latin “tolerare”, most commonly means to “accept or endure (someone or something unpleasant or disliked) with forbearance”[2].

In Western culture, the ability to tolerate without complaint is seen as a positive strength in many ways. This value finds its origin in ancient Greece where practitioners of Stoicism praised the capacity for the mind to remain detached from external desires and fears and to use logic and reason to attain happiness (eudaemonia). It then evolved under Judeo-Christian’s influence to focus on the capacity to endure suffering without rebelling nor questioning the will of God. Nowadays, being able to tolerate pain is a signal of “toughness”, a high-ranked value in our competitive society (ies).

Additionally, tolerance is seen as a moral obligation. After centuries of religious wars that disseminated the European populations and opened the door to the cruelest aspect of human nature, the concept appeared as a way to ensure the cohabitation of Catholics and Protestants within the same kingdoms and under one secular king or queen. Voltaire’s Treatise of Tolerance (1763) is the cornerstone of this new worldview. The French Revolution carves in stone this ideal of living together through the new republic’s motto: “Freedom, Equality, Fraternity”[3]. While the Law ensures the freedom to choose your way of life and the principle of equality of rights and obligations (Declaration of Human Rights), Fraternity is added slightly later to emphasize the shared heritage of all human beings and the necessity of a strong social link among individuals and groups to build a peaceful society. Colonization, slavery, and dictatorships have shown throughout modern history that the ideal of tolerance is fragile and not unilaterally recognized by everyone. With the vivid memory of the periods where the lack of tolerance caused the death and misery of millions of people across the globe, the protection of the principle of tolerance became more and more a role of the law and less a question of fraternity. Today, people are polarized on the political spectrum, either claiming that everything has to be tolerated or that one has the right to not tolerate what one assesses as “intolerable”. Tolerance is seen as a passive fact, rather than to empathize, better understand, and challenge some opinions or some situations.

Like all values, tolerance hence has its lights and shadows. While it can be a beautiful tool to reflect on one’s challenges and regain ownership through self-awareness and self-control to grow (Stoicism), as well as a way to create and sustain a peaceful and inclusive society where differences enrich the group, it can also foster fatalism, deny of one’s needs, and a passive and disinterested acceptance of other groups and alternatives.

In the case of our client, tolerance means that Anna doesn’t feel the right to do something about her Sunday scaries and rationalizes her lack of action with excuses such as “everyone feels the same”, or “I’m an adult, I should be able to handle my stress”. Tolerance becomes passivity, and avoidance and causes people to remain in sub-optimal situations.

Why Do People Tolerate Sub-Optimal Situations?

If this kind of tolerance is detrimental to people and their well-being, what can explain that so many of us are adopting this strategy – sometimes over very long periods? Is it possible that people find some benefits in remaining in such situations?

Change happens when the pain of staying the same is greater than the pain of change. Tony Robbins[4]

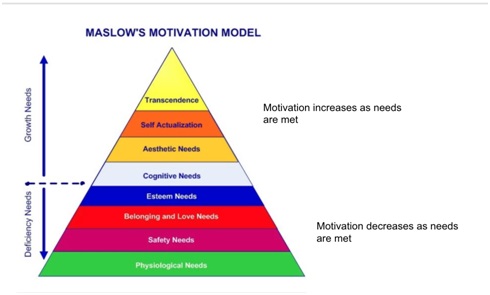

The theoretical model of the hierarchy of needs, developed by A. Maslow in 1943, can help us consider this question[5].

Maslow’s Framework[6]:

Maslow originally identified five levels of needs. In the 1970s, he added 3 more levels of needs to his framework.

Maslow originally identified five levels of needs. In the 1970s, he added 3 more levels of needs to his framework.

- Physiological: essential resources to the survival of the individual, like air, water, food, sex, clothes, shelter, sleep, and health.

- Safety: physical safety, financial safety, and emotional safety.

- Love and belonging: a sense of being accepted and being part of a social group(s). Such needs include family, friends, and social acquaintances, as well as intimacy.

- Esteem: needs for respect from others, status, recognition, fame, attention, as well as the need for self-respect that cover strength, competence, mastery, self-confidence, independence, and freedom

- (Added in 1970) Cognitive: creativity, predictability, curiosity, and meaning

- (Added in 1970) Aesthetic: appreciation and search for beauty and balance

- Self-actualization: need to realize one’s potential.

- (added in 1970) Transcendence: the individual is compelled to use their capabilities and resources to achieve something beyond themselves (e.g. religion, spirituality, altruism…).

According to Maslow, those needs are not equal. The four lower levels are described as “deficiency needs”, or “d-needs”. When those needs are not met, the individual will either experience some physical reaction (physiological needs) or anxiety and stress (safety, love/belonging, esteem needs). The marginal value of the resources required to meet such needs is decreasing. Once an individual has found the resources to answer the d-needs, their motivation to add more of such resources declines. On the contrary, once the individual starts filling the needs at the top of the “pyramid” (cognitive, aesthetic, self-actualization, and transcendence, or so-called “being needs” or “growth needs”), the motivation for further growth increases.

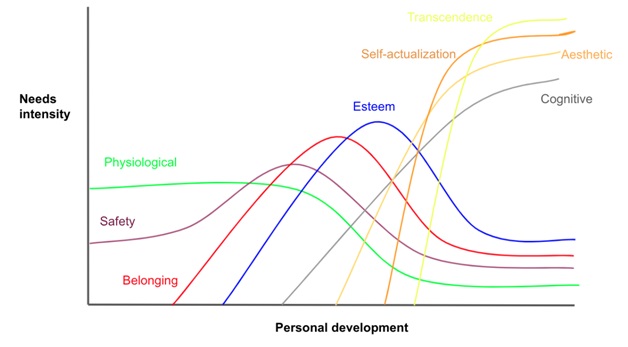

While Maslow’s framework was mostly pictured as a pyramid, giving the impression of a linear progression from basic needs to higher needs, Maslow himself recognized that needs of different levels can overlap and co-exist at a specific moment in the life of individuals. The reality of human needs might therefore look more like the graph below:

Alternative illustration as a dynamic hierarchy of needs with overlaps of different needs at the same time (adapted)[7]

Let’s come back to Anna. At this stage in her life, she finds herself at the crossroad between the D-needs and the Being needs. She has acquired the resources to ensure her survival and safety, she has a lovely family, good friends, friendly co-workers, she enjoys a high level of esteem from her environment (and even a fair level of self-esteem). At the same time, she has started developing skills in her career and her free time that allow her to climb the curve of the “being needs”. Something in her pushes them to commit fully to her development journey, to feed her hunger for intellectual challenge, to quench her thirst for beauty and harmony, to pursue her quest for joy and purpose. Alas, another voice pleads for her to remain focused on the d-needs and goes like: “Anna, your dream of being more is commendable, but you and I know that the resources we need to survive could disappear at any time. We should stop dreaming and keep focused on maintaining our current state, don’t you think? That is what every reasonable person would do!”

Let’s come back to Anna. At this stage in her life, she finds herself at the crossroad between the D-needs and the Being needs. She has acquired the resources to ensure her survival and safety, she has a lovely family, good friends, friendly co-workers, she enjoys a high level of esteem from her environment (and even a fair level of self-esteem). At the same time, she has started developing skills in her career and her free time that allow her to climb the curve of the “being needs”. Something in her pushes them to commit fully to her development journey, to feed her hunger for intellectual challenge, to quench her thirst for beauty and harmony, to pursue her quest for joy and purpose. Alas, another voice pleads for her to remain focused on the d-needs and goes like: “Anna, your dream of being more is commendable, but you and I know that the resources we need to survive could disappear at any time. We should stop dreaming and keep focused on maintaining our current state, don’t you think? That is what every reasonable person would do!”

Tugged between those two forces, Anna falls into the trap of passive tolerance of the situation. Her brain rationalizes her anxiety of losing the foundation of her existence by providing all kinds of “good and reasonable” reasons to maintain the status quo. Anna is not aware of this choice and of the other path that she could take. The voice longing for further needs to be met as well becomes less audible. It only bubbles up on Sunday evenings in the form of the scaries.

Embrace

Embracing a change, a difficult situation, a loss, an opportunity, can be defined as a commitment to a quest toward a more fulfilling life, with an emphasis on the journey rather than on the outcome.

How nice it would be if we were fearless! How nice it would be to embark on new adventures, wrapped in shiny armor! How nice it would be to only keep the eyes on the price of the quest and defeat every monster encountered on the path, with no urge to disappear from the surface of the hearth, destroy everything around us, or become a salt statue – or, as we commonly say, experience the fight-flight-freeze response!

However, fearlessness is not a thing we can – or should! – hope for. Evolution has shaped our brain to benefit from fear and ensure survival. In other words, fear is a precious tool, not a defect in the design of the human brain.

At the same time, fear so often gets in the way of projects, changes, and growth that it should not be allowed to control too much of our behaviors. An alternative to utopian fearlessness (and an endless waiting for it) is bravery. Elizabeth Gilbert defines bravery as the act of “doing something scary”[8]. She describes how fear is present through any of her creative endeavors and how, instead of denying it, she invites her fear to come along on the road trip of her creative work. She gives fearsome space, the very right to be there, but in no instance the right to influence the journey.

To bravely face fear, three main deep beliefs are most helpful. Two of them are linked to the ways of seeing oneself and one’s place in the world, while the third one is related to one’s motivation.

- Renée Brown advocates for the acceptance of showing vulnerability in our daily life[9]. To have the “willingness to do something where there is no guarantee [of success]”, a key is to have a strong sense of worthiness.

- Trust is often linked to the ability to overcome fear and engage in brave acts. That kind of trust is twofold and encompasses both the trust in one’s capability to overcome challenges and grow[10], as well as the trust that “things will work out at the end”. Some call this “trust in life”, “trust in the universe”, “trust in your guardian angel”. In the language of positive psychology, this kind of trust is very close to optimism.

Everything is going to be fine in the end. If it’s not fine, it’s not the end. Oscar Wild

- Viktor E. Frankl was one of the first to articulate the power of having meaning in life[11]. Others have called this driver “purpose”, “passion”, “calling”, “faith”…The common aspect of such terms is that they give the individual a north star to make decisions on the next steps and on how to show up in life, a reason to overcome roadblocks and push their boundaries, and a sense of joy, fulfillment, and gratitude. Martin Seligman counts Meaning as one of the key elements of well-being[12].

Those three beliefs are interrelated and tend to nurture each other as they develop.

The Impact of Replacing Tolerance by Embracement

Over a few weeks of listening, journaling, and reflecting, Anna went through different stages. She first recognized and admitted to herself that her current situation was suboptimal. She then accepted that it was her responsibility to change it – or to decide to live with it. In other words, she accepted that she had a choice and that by “tolerating” the situation, she was choosing this situation. Finally, she embarked on a journey to make the situation better. When she embraced this choice, Anna had no clear vision of what the end goal could or should be. Her commitment was not about a specific outcome but rather about a process that encompasses experiment, discovery, learning, failure, and further opportunities. Such a journey required Anna to trust and love life and herself, as well as to believe that she has the right to improve her life and invest in herself, and to focus on the learnings and joyful moments in the process.

By embracing the totality of what represents a journey to improving one’s life, the individuals don’t not only have a chance to honor themselves by letting go of a misplaced tolerance, but they also develop the skills and ability to learn and love on the way. This flexible way of getting closer to a richer life accounts for the unexpected and keeps the mind open for finding alternative ways to overcome roadblocks – or to choose new goals and priorities along the way.

Hence, embracing has some similarities with the framework of Fixed vs. Growth Mindset[13]. Carol Dweck describes how people who believe that intelligence is not an inborn attribute and that one can rather improve skills and capabilities through work and practice are more likely to focus on the process rather than the outcome and to achieve their goals, or at least to make progress. On the other hand, people convinced that intelligence is an attribute allocated at birth spend more time and energy trying to prove to others that they are smart, which leads to an unproductive focus on the outcome at the cost of learning and growth, and even some time at the cost of integrity.

Hence, embracing has some similarities with the framework of Fixed vs. Growth Mindset[13]. Carol Dweck describes how people who believe that intelligence is not an inborn attribute and that one can rather improve skills and capabilities through work and practice are more likely to focus on the process rather than the outcome and to achieve their goals, or at least to make progress. On the other hand, people convinced that intelligence is an attribute allocated at birth spend more time and energy trying to prove to others that they are smart, which leads to an unproductive focus on the outcome at the cost of learning and growth, and even some time at the cost of integrity.

Embrace vs. Tolerate Fostering Accountability and Cultivating Learning and Growth

The very first step for clients is to gain awareness about where they stand on the dichotomy between tolerating suboptimal situations and embracing change and growth. The use of both terms as “power tools” by the coach helps the client reframe their perspective and see their life and their potential through a more empowering perspective.

The next step for the client is to leverage this awareness in their life by taking action and by learning. The coach can support this journey by fostering accountability and cultivating learning and growth.

Evoking Awareness

Examples of powerful questions:

- “What is the challenge to live a fuller life now?”

- “What does it cost you to tolerate the current situation?”

- “What would your life look like if you embraced the challenge?”

- “What permission would you need to give you to move forward?”

Wheel-Of-Life Tool

The tool of the Wheel-of-Life[14] is particularly interesting in the context of a client who is tolerating suboptimal situations as it allows to get a differentiated image of the dimensions that are particularly affected. It also reduced the impression that the challenges to tackle are too big to be addressed. Finally, it invites a discussion about the repercussions of a change in one specific domain on the other areas of life.

Taking Actions

As the purpose of choosing to embrace life and change is not to per se achieve more, but rather to enjoy the journey and make the most out of it, the coach’s role is to help the client:

- Decide which actions are beneficial

- Reflect on the learnings and potential for growth of each action

- Celebrate steps forward, independently from the size of such steps

- Build on experiences to apply the learnings to other aspects of the client’s life

- Become more autonomous and accountable

- Build self-confidence through actions

- Enjoy the journey

- Constantly refine their alignment with their values and purpose

References

Joe Pinsker, “Why People get the “Sunday Scaries”

Francine Carrier, “Liberté, Egalité, Fraternité, l’Histoired’une devise”

Saul McLeod, “Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs”, Simply Psychology

Elizabeth Gilbert, Big Magic, Creative LivingBeyondd Fear

Renée Brown, TedTalk

Carol Dweck, Mindset, the new psychology of success

Viktor E. Frankl, Man’s Search for Meaning

Martin Seligman, “Flourish, A visionary New Understanding of Happiness and Well-being”