A Research Paper By Leigh Griffin, Management and Agile Coach, IRELAND

(Re)Orienting a Software Team: The Challenges Facing a People Manager in a High-Performing Industry By Dr. Leigh Griffin and Gerard Griffin

Software Engineering teams are often classified as high-performing, with their membership made up of skilled knowledge workers. Teams follow methodologies and best practices to produce sustainable value. As an industry, it is still maturing, with those very best practices still being worked out. The role of the manager in software is to help the team to grow and to work most optimally and efficiently possible. Managers are natural change agents and are the embodiment of a continuous improvement mindset. When a team is high-performing, a visible gap emerges from where the team began, to where they are right now. That gap represents tangible improvements that are revenue-impacting. The presence of the gap often causes stagnation in the continuous improvement mindset, wherein the team changes to a holding pattern to maintain and sustain the gains. This pattern of behavior has now been exposed due to an enforced change in work practices due to the results of an unprecedented pandemic. This paper explores how a manager attempted to re-orientate an already high-performing team towards a new process, by harnessing the existing mindset. Change management is already an area of challenge and motivating a team, who have a visible and metricized improvement already established, required a very specific managerial approach. We explore the role clarification required and the new competencies needed for managers to successfully reignite the continuous improvement mindset in their teams to help them constantly challenge the status quo and continue to ask the question of why?

Keywords: Coaching, Continuous Improvement, People Manager, Trans-formation

In 2001, the Agile Manifesto, Beck (2001), was published to establish a set of guidelines for software development best practices. In the 20 years that have passed since its publication, frameworks, tools, and methodologies have emerged to fall under the umbrella of Agile. Scrum, as documented in Sutherland & Schwaber (2019), is one of the most popular frameworks that embodies the mindset of Agile development and has become ubiquitous in the software industry. The ability to quickly iterate on ideas, delivering in a value-driven, customer-centric manner, has transformed the development experience. Software teams operating through Scrum are invariably more resilient to a VUCA (Volatile, Uncertain, Chaotic, Ambiguous) environment, a phrase de ned in Bennett & Lemoine (2014). Teams are experimenting more with variants of Scrum as noted by Robinson & Beecham (2019), from team size as seen in Gancarczyk & Griffin (2019) to cross proliferation with other process improvement approaches, such as Kanban, as seen in Nikitina et al. (2012). At the heart of Agile is the Continuous Improvement (CI) mindset, driven, in the case of Scrum, by an Empirical Process Control model, wherein changes are grounded within data. The opportunities to introspect and discover improvement opportunities happen frequently in Scrum, with work divided into a timeboxed period, punctuated by ceremonies, with each ceremony a potential improvement opportunity. The bene ts derived from working this way, and making incremental change, quickly show a visible delta from the previous method of working. For software teams, that previous mode was predominantly a Waterfall model of delivery, so-called because of the phased and deliberate approach to moving a software project forward. The transition towards Agile has enough bene ts compared to that mode of working, as both Palmquist et al. (2013) and Goksu (2018) observed, to en-tice teams in and practice it for themselves. The improvements in quality and productivity (Ahmed et al. (2010)) are particularly obvious and help with leadership backing through positive customer-centric improvements. With such visible improvements from a simple adoption model, the motivation to explore other process improvement methodologies is low. There exists no real motivator, as the current approach is already yielding attractive results, to question why we cannot build upon this and improve. In early 2020, a global pandemic has shifted the world unexpectedly into remote work which brought numerous challenges as seen in Brynjolfsson et al. (2020). As the prevalent mode of executing Scrum assumes that the team is in co-location, this represented a challenge for teams. Scrum advocates strongly for in per-son execution for the most optimal results and control for the team, with a strong motivator being the presence of the customer and team working in unison in the same physical environment. Previous work by Grin (2021) noted that in-person interactions masked the heavyweight nature of Scrum and the shift to remote work has exposed that. Fatigue within teams, driven by the over-reliance on video conferencing and asynchronous communication while remote, is now being experienced due to an overhead incurred by both the pandemic and the communication style that Scrum demands. The result is a weakening of the Scrum fundamentals in teams, with the previously visible gap diminishing, albeit still an improvement over the old way of working. Modi cations were therefore being made to accommodate the new normal that teams are experiencing with the software industry looking at the hybrid or remote models going forward Grzegorczyk et al. (2021).

Lean has seen wide adoption in more traditional manufacturing industries, with its origins in the 1930s within the Toyota Production System. It was de ned more formally by Womack et al. (1991), who explored key principles, which led to an emerging Lean mindset, focused on productivity and continuous improvement. This Lean approach has now certainly entered the zeitgeist and enterprises are embracing Lean with an end goal which can be described as an e ort to reach the status of a Lean Enterprise. That goal is achieved not in isolation, but through a multifaceted, holistic transformation that is at a tooling, leadership, culture, and mindset level. Indeed Sanjay Peter (2006) explored the concept of Lean as a philosophy, focusing on the relative success attained by companies that viewed Lean as a philosophy, rather than another strategy. Yet Lean, as an approach for software engineering teams to utilize within their Agile strategy, is present in approximately 1% of the industry, according to the 2020 State of Agile report published by-digital.ai (2020). The enterprise-scale implementation and execution of Lean may explain the reason why software teams, who often operate in a siloed mode, may not have turned to Lean as an approach. The research centered on the actions taken by a manager within Red Hat, a software engineering company with a mature sense of culture and identity, who identify ed this challenge and successfully re-oriented the team’s processes to include Lean. This was a high-performing software team of 27 people, which was operating in a Scrum environment and over a year were exposed to and calibrated towards a Lean method of thinking, planning, and execution. This journey is captured in previously published work by Grin (2021). A move to any new paradigm of working comes with risk but Camargo (2017) summarised the double-edged nature of Lean as a philosophy: If it is not completely understood and it is not implemented strategically, that involves the study of contextual factors, the results obtained could end up hurting not only the performance and productivity of operations but also, the mental and physical state of the people who are subjected to those results. With that viewpoint in mind, the managers of the team had to delicately balance the transformation and make holistic changes to their role and indeed their approach to dealing with the team members. The rest of this paper will now focus on the manager’s role in enabling the transformation to occur and exploring a method embraced to sustain it. The focus will be on the engagement and change management challenges that face high-performing teams with the manager’s role central to the success or failure of that. An analysis of the importance of coaching and the employee’s cultural experience of transforming one mode of high performance to another will also be explored.

Engagement in High Performing Teams

Software engineering as a discipline is still in its infancy compared to more mature domains. The software industry grew rapidly in the late 90s due to a combination of infrastructure availability in the form of home broadband and more affordable and accessible devices (Norman & Venter (2016)). With the rapid maturation, new roles and skills are still evolving as the market is guiding the growth and style of work. This has led to a global shortage with academic institutions attempting novel conversion courses to try and retrain people into this newly formed role as Meade et al. (2019) note. The nature of software engineering is that of a knowledge worker-centric role. Knowledge workers accumulate huge experience and bring both tangible and intangible bene ts to a company. The ability to move into market segments, the ability to cross-train and improve the skills within the company, and the ability to meet customer demands hinge on the engagement of the knowledge worker. With the shortage of skills, the roles are well paid to minimize the risk of sta turnover and to fully leverage the bene ts of having those skills within the company. Knowledge workers form the core of high-performance teams and working in pro table organizations they need to be positively engaged by management.

Engagement has been de ned as the emotional and intellectual commitment to the organization and as noted by Jiang et al. (2016), connects employees with cognitive and behavioral consequences that help the organization’s goals. When de ned this way, engagement is often interchanged with involvement and dialog, which a manager plays a key role in fostering. Saks & Gruman (2014) observed that employee engagement drives several positive organizational outcomes, such as pro stability, while Kular et al. (2008) views it as a competitive advantage. Robinson et al. (2004) observed key drivers of engagement, which are required in all working environments but are more crucial to the success of engaging a knowledge worker. Those drivers included meaningful and challenging work, autonomy in decision making, career opportunities, organizational concern for employee wellbeing, and a sense of feeling valued and involved. Knowledge workers are driven to innovate and accumulate more knowledge for their self-growth and that of their companies, software engineers in particular focus on impactful work in a societal sense, with technology being both pervasive and ubiquitous, their contributions could be life-changing for others. The very nature of software engineering ensures that the right ingredients are present to allow engagement to take root and when paired with an approach to building software, such as Agile, which places a high emphasis on autonomy and the value of the team to the company, you have a magnifier for an engagement present. Due to both a social and environmental perspective surrounding the knowledge workers and the market, managers need to be aware of the role they can play, which can positively or negatively impact engagement. High-performance teams need to sustain the very CI mindset that brought such organizations to a high performance / high pro t position in the first place and the manager’s role has the success of the team, and by extension the company, as a focal point. The engagement of Agile teams in such circumstances was succinctly described by Bakker et al. (2011) who stated that through engagement, people express themselves cognitively, physically and emotionally, whilst performing their roles. This is often characterized by high energy levels and a strong personal identity cation with their work. That high energy level can lead to what Little & Little (2006) calls organizational citizenship behaviors, a highly desirable trait, but one where the will manifests itself in working longer hours and trying harder. That pattern of behavior is a trait of burnout, the antithesis to engagement, which Demer-outi & Sanz Vergel (2014) denote as a gradual emotional depletion and loss of motivation. Mosadeghrad (2014) linked burnout with the possibility to generate poor workplace morale, showing that if strategies for engagement are mismanaged, it can have a negative effect. The handling of engagement in knowledge workers was observed by Geary & Dobbins (2001), who spoke of a paradigm shift from management of control to the management of commitment. That commitment extends to the philosophy of the management, with Emiliani (2006) recognizing that managers are required to learn the use of new tools and processes, as well as the development of a new set of beliefs. With engagement being highly sought after as an approach to enable change management and sustain profitability and with the prevalence of burnout within software engineering well established, as both da Silva et al. (2016) and Raman et al. (2020) note, the delicate balancing act of tuning engagement levels falls to the role of the manager. The next section examines this role in more detail.

Supporting the Role of the Manager

To enable a high-performing team to continue that level of performance through a change management process, several supports need to be in place. From the role clarification of a Manager as an agent of change and as an empowering people-centric manager, through to key skills and tools, this section will explore what was put in place in Red Hat to help this transformation to succeed

Managers as Agents of Change

Change is now empowered by and realized through the management team and their relationship with the workforce they manage, rather than their ability to lead and push a change through at an Individual Contributor (IC) level. Emergent change, as de ned by Bamford David & Forrester Paul (2003), is the style of change that is prevalent in Agile teams. It emphasizes bottom-up action, rather than top-down, and Heyden et al. (2016) identified managers as key enablers to initiate change and to help understand employees’ dispositions toward change. With managers communicating more, the use of language as an engagement medium for change becomes important. Jansson (2013) viewed change from a linguistic perspective as a social construction of talking, such as discursive manifestations, struggles, or recon-textualization, of which the manager’s ability to project thoughts into words becomes a crucial skill. The author believes that discourse is the key site in which change happens, as change is not fixed, but assembled through various discourses. Through that lens, they identified that the usage of wording in phrasing communications about organizational change should be as familiar as possible to the community impacted. Managers help to guide the overall project’s success through accountability-driven ownership and their role as communicators within the organization, promoting the project’s status and objectives up through management chains and laterally through program management activities. The manager thus has a very strong influence over how work is tracked, consumed, organized, and reported. That ownership lends itself to the manager being a change agent concerning methodology and approach. Managers have the authority to impose such changes on teams, despite a prevalence for bottom-up. The manager can suggest and guide, however, their title and role allow for the suggestion of change-related actions to be misinterpreted as a mandate, which is a constant risk when the manager acts in a guiding manner. With the move towards a new way of working, an interpretation of the change towards the new model could be viewed as a management fashion. Management fashions follow a predictable trend that Gill & Whittle (1993) documented with stages ranging from the invention to dissemination, to acceptance. Disenchantment and decline ultimately follow where the idea is abandoned. Benders Van Bijsterveld (2000) observed that fashions are designed to be temporary rather than a structural in influencer, which Lean is, and observed that those affected by such changes will tend to associate the fashion, in this case, the imposition of Lean principles, with what happened to them at a personal level, rather than with an abstract, theoretical construct, that Lean promotes through its philosophical grounding. This puts a change proposal, wherein the objective is to go from one high-performing mode of working to another, in a very fraught position. It allows for the interpretation of the change to be that of a fashion and risks the manager becoming a driver and forcer of change rather than an enabler. To enable this transformation to succeed, the core role of the manager to be that of a manager for the people needs to be explored.

The Role of the People Manager

Software Engineering Managers traditionally required a command and control mindset to e actively run a software team and a great manager possesses many roles and skills as described in Kalliamvakou et al. (2017). Managers were typically promoted from technical ranks, with deep technical knowledge and experience providing guidance, leadership, and mentorship to teams. The manager’s role blurred that of an IC, often taking on work within the team environment to help to lead from the front. The competencies required to excel as a Manager in that paradigm were identical to that of an IC, making the manager more of a strategically placed peer, directing and commanding rather than a manager disconnected from the work. A negative impact of this style of working was the mismanagement of talent. This occurred in the form of a lack of focus on the nurturing of employees’ careers and the competency building to attain next-level promotions was made a secondary concern. This approach changed over time as employee turnover increased within companies due to a lack of focus on career growth and often due to the dominating appearance of a technical manager, stirring room for growth. This e actively created a disengaged workforce and with the market opportunities high and competitive salaries on o er, the switch to another company was an easy decision. The role in many companies evolved into that of a People Manager, a role with new skills and demands as observed in Ho man & Tadelis (2021). While companies still value the technical mindset and background, the focal point in a day-to-day capacity has switched away from IC-oriented tasks towards that of strategic involvement in the team and product direction and has been available for the people. That availability for the people is crucial to help project the culture and values of the organization into the team and the individuals. With the market being so competitive and a key driver of engagement centered around feeling valued and involved, the culture and values intersection is where managers want to get their ICs focused, to develop an attachment and an attraction of the company that extends beyond the remuneration and makes a cultural identity between the company and the employee.

In larger enterprises, a matrixed organization exists, with job roles and skills segmented with dedicated managers able to better guide careers based on their own experiences. Scrum teams are inherently cross-functional, meaning that managers in one vertical, interact with and communicate with employees who are not their direct reports. Continuity in management style approaches, and interactions are thus key. Within Red Hat, manager pro-motion tracks, like IC tracks, are competency-based and extend across the horizontal layers of the company. This ensures that the management team has a level of consistency concerning their level of training and capability, with a key focus placed on their role as cultural and value ambassadors within the company. Being available for the people thus manifests itself in both a team environment and more importantly in a 1:1 capacity, holding conversations frequently with each direct report. The goal of those 1:1s is to e actively communicate the project goals, helping the employee understand the what and the why questions, that is to say, it is to contextualize what the goal of the project is and why it is important. That creates a separation where the employee helps to derive and drive how that is executed and carried out, with no mandate from the management in this area. That gives the autonomy and space to arrive at solutions and promotes a trust-based relationship, where the manager can guide mentor, and coach as needed. Another key part of the 1:1s is to help guide conversations that should be primarily employee-driven, giving a total focus on what their topics of interest are. A final, but a crucial aspect, is guiding them through their career by helping them to identify competency gaps and collaboratively planning on how to address them. This focus on people is yielding better retention rates and companies can grow their talent pool, pivoting into skill gaps and niches more easily.

With this role clarification, changing the approach of the team’s work from both a tooling and mindset perspective can be enabled through the 1:1s. The context setting, the establishment of the Why, and leaving it be employee-led allows for a menu of change to emerge. Handling the challenges and difficulties that emerge during the change journey now requires additional support for the manager, the development of a new competency and skill, that of coaching.

The Role of Coaching for Continuous Improvement

Coaching is fundamentally forward-looking and pairs well with the concept of continuous improvement Alstrup (2000). Coaching is thus a powerful tool for people managers, both to grow their career and that of others (Burrell (2018)) and appears prominently in job specifications as a desirable trait to possess. It has several nuances that need to be considered.

The Coaching Manager: A Contradiction?

Coaching is where a coach partners with a client to inspire them to maximize their personal and professional potential. A crucial element of the coaching is the desire by the client to want to be coached, it cannot be a forced encounter or experience Mccarthy & Ahrens (2011). A contradiction thus exists in having a manager as a coach, with employees feeling a sense of obligation to turn up to meetings with their manager to talk about their growth, their challenges, and their concerns. Those very topics are typical coaching conversation topics, however, the manager’s role naturally blurs that of coaching, mentoring, teaching, and directing, making the core competencies, as de ned by Gri this & Campbell (2008), very di cult to practice in isolation. There is also an issue of trust, openness, and psychological safety in the coaching relationship. The client can and will feel vulnerable and weak, sharing their inner fears and concerns. Within the software industry, an imposter syndrome mindset is rampant (Bravata et al. (2020)) and the willingness for an employee to share such concerns to a manager that holds ultimate responsibility for the total rewards package, such as pay bumps, and bonuses, to career progression. This can make for a very contacting experience. The challenge thus exists for the manager to reframe the approach to coaching to be more involving and more focused on the willingness of the client to come forward with topics.

Establishing the Coaching Manager: Psychological Safety

The concept of psychological safety as a core component of high-performing teams is explored by Edmondson (2018) and is now taking root in the software industry (Lenberg & Feldt (2018)). A fail-fast mentality, where blame is not part of the vocabulary is a cornerstone of psychological safety. For innovation, the ideation process of the team, those with the most domain knowledge of the system, is crucial to ensuring that both novel and realistic features are put forward. The lack of fear of failing and the absence of ideation ridicule are ingrained in the mindset of Agile teams. The Agile philosophy of continuous feedback loops with the customer, of delivering in time-boxed increments, of delivering imperfection to gain insight allows for a base layer of safety to exist. The manager’s role is to foster that feeling and ensure that they faithfully represent the needs of the team to senior management. This gives the team the protection, transparency, and trust needed and a consequence of that is a more open relationship with a manager. The manager, therefore, becomes more of a peer, than a supervisory role, as the knowledge-driven workforce respects the role that the manager is playing in helping to protect the team and empower and engage the team members. With trust built up, and the manager’s role has evolved to focus on the people, there is now an opportunity to reimagine 1:1 conversations with team members. A total disconnect from the technical day-to-day is required. Through the Agile ceremonies, there exist numerous touchpoints in a given week for the manager to gain that level of information. With the technical project feedback loops in place, it creates an environment where the manager can engage the employee on topics of interest to the employee. The main goal of a people manager is competency building, to round out skill sets, o er feedback, and to attempt to foster a mindset of continuous improvement. With the employee leading the conversation and the manager equipped with the domain knowledge of the career trajectory and competencies required, the baseline expectations for a coach-client relationship is thus possible

Coaching Models

Coaching Models exist to o er the coach a guided means to bring a client from their current state to where they want to be. The purpose is to create a framework for guiding the client through the phases of the coaching lifecycle from goal setting, to establishing the current state, through a series of exploratory options before settling on a plan of action with awareness raised of obstacles, supports needed, and a focus on how the plan will achieve the initial goals. There are numerous coaching models in existence (Kunos (2017)) and every coach evolves their model to match the blend of their experience and their clientele.

With the challenge here of moving a high-performing team between process improvement, the ultimate goal is fostering that CI mindset. That is the journey, the destination may and indeed should change over time, as new ways of working are uncovered and new approaches and techniques are integrated into the team. Therefore, a novel coaching model is proposed to help teams foster a CI mindset, wherein the coach and client relationship explores a topical space over several months. The model is based on four key components:

- A current state and future state analysis

- A backlog of problem statements that will bridge the gap An Organisation, Passion and Talent exploration

- A Scrum inspired ceremony approach

The Continuous Improvement Coaching Model

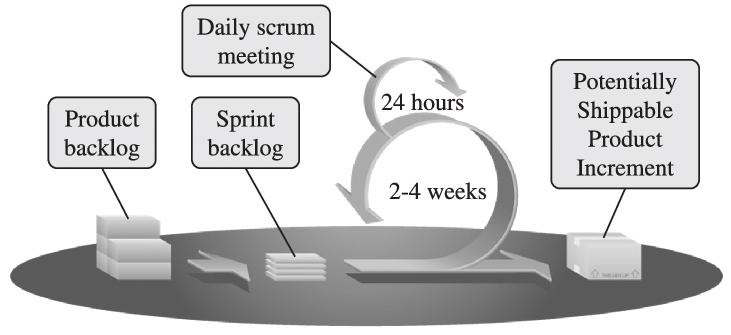

Scrum is cyclic and Figure 1 shows the main ceremonies and feedback loops involved.

Figure 1: General Idea of the Scrum Process taken from Carvalho et al. (2011)

Scrum is an interactive process, constantly checking the pulse of the team, ensuring that the goal is still on track to be achieved. It includes a positive feedback loop in the retrospective and review ceremonies. The retrospective allows for a self-appraisal of both the performance of the team in pursuit of the goal and indeed the process they followed. The review is the showcase of what was achieved in that timeframe. It is intended as a pause and inspection opportunity, to evaluate what was completed and how that now potentially changes the future goals, which is where the planning ceremony comes in. The Planning is driven by a prioritized backlog which is re ned after the Review phase to learn from the experiences to date and to guide what the focal point should be for upcoming work. The backlog is prioritized with the most valuable item at the top. The backlog is organic, with items capable of being added or removed as we discover them over time. When the backlog is exhausted, the project is deemed complete.

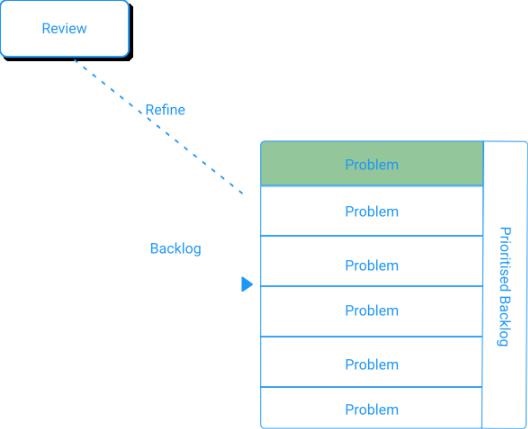

Figure 2: The Coaching Topic Backlog

Through integrating this approach into a Coaching model, the client has familiarised themselves with the concepts due to the day-to-day execution of the same ceremonies and patterns. This muscle memory helps to guide the conversations to the most valuable and pressing topic that the client wishes to address. Figure 2 shows the creation of a set of problem statements that are prioritized and re ned to ensure the most valuable and pressing problem is addressed first.

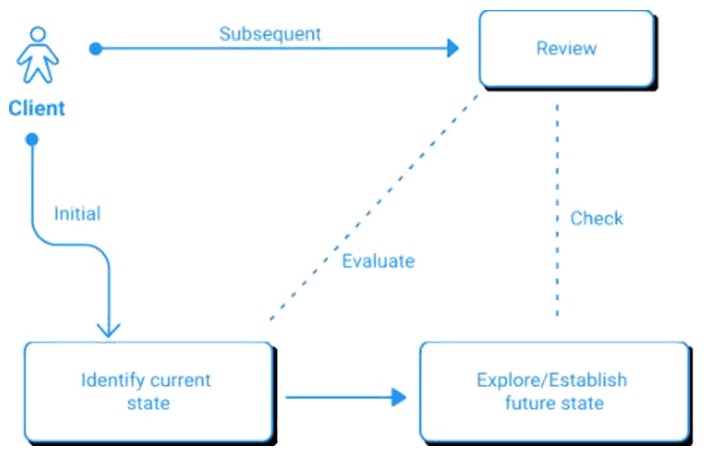

Current State and Future State

The concept of a Value Stream Map (VSM) centers around analyzing a process to gain an insight into the current state, identifying improvements to transition to a future state, and is a mature Lean tool (Gunaki et al. (2015)). Within coaching, this is the technique practiced in individual sessions, as the client charts a journey of understanding towards a goal. In continuous improvement, the goal here is to develop competencies to transition towards a new state. That state may be skill-based, role-based, process-based, or team-oriented. With the nature of Agile teams, it takes several iterations, with each ranging from 1-4 weeks, to see whether a change has had a positive or negative impact. This means that any continuous improvement initiative is of the order of weeks and months. The mindset changes and indeed competency development is of a similar order of time. This changes the pattern of how a client engages, as the goal here should be to evaluate where the client stands right now (the current state) and to question and check if the future state is still valid. Within Agile teams, the future state is often the delivery of a project to a customer. During the sprint process, at each boundary, there is an opportunity to review the output, with the output potentially shippable and usable by the customer. While the customer at ideation phases intended on a specific future state, the development and tactile feedback model employed within the Scrum framework means that the customer may opt to change course, settling on an alternative solution or future state based on the learnings uncovered. This reflects itself as actions upon the Backlog and Figure 3 shows the coaching agreement steps where the Client and Coach explore the states.

Figure 3: The Coaching Agreement: Current and Future State Exploration

An Opt View of the World

Within Red Hat there exists a power tool for people managers known as the Organisation Passion and Talent (OPT) model, which is visible in Figure 4.

Figure 4: The OPT Model

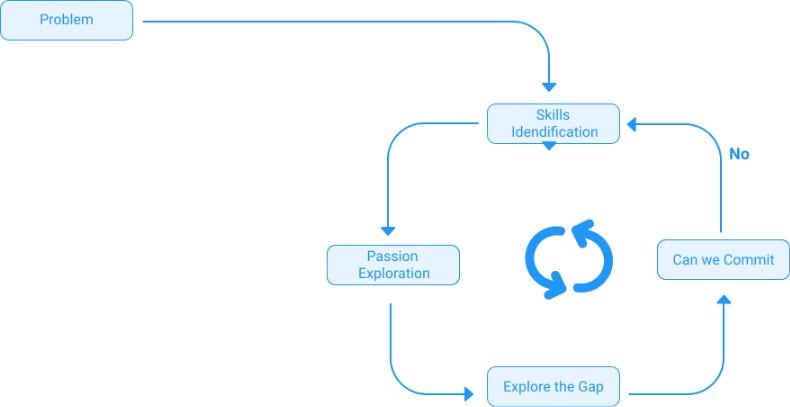

The OPT helps employees to identify what they are passionate about and what they have Talents in. The overlap between Passions and Talents leads to a very engaged employee, who has both the skills and motivation to excel. The crucial pairing here is the Organisational role that the employee plays. If they are in the right role, with the right passions and talents, the employee is operating at their career-best. Their talents and passions are being focused on value add and the contribution is highly visible. People managers in Red Hat use this tool as calibration of sorts, to help bridge the gap between Passions and Talents, to help employees identify upskilling opportunities, and to enable, often through internal mobility, the employee to nd the right organizational role wherein they can deliver the most value and simultaneously excel within their career. The result of an OPT driven people manager approach is engaged employees and a lower risk of turnover of key talent. Integrating this into the Coaching model is seamless for the employee experience and focuses the problem-solving aspect towards the passion and skill-based gaps that might exist, with the goal being a commitment to a plan that can bridge the gap. Figure 5 shows the cycle that the coach goes through to guide the client towards an action plan that they can commit to addressing the problem.

Figure 5: The Coaching Cycle

The Model in Practice

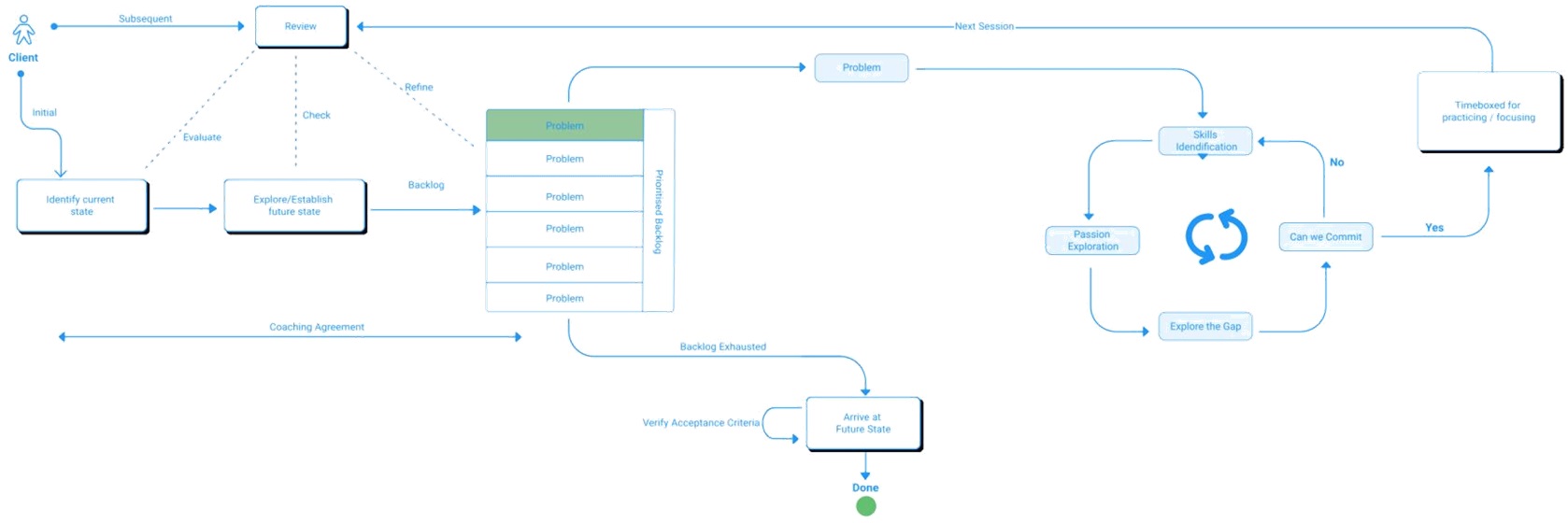

The full model is visible below in Figure 6 and a description of the model in practice follows:

Figure 6: The Continuous Improvement Coaching Model

A client works with a coach to identify a current state and explores a potential future state that they wish to move towards. Collaboratively, the gap is identified between the states and this forms a backlog. While the future state may be very well defined for some clients, for most, this will take several sessions to explore and eventually establish the future state. The future state should be testable and discoverable when the client arrives there, so identifying acceptance criteria to validate the journey is an important collaboration between the client and coach. The backlog is an ordered prioritized topic list, that organically grows and contracts as time moves on. The backlog charts the journey towards the future state and once exhausted, indicates that the destination state has been attained. A final session to validate the future state and retrospectively look back on the journey signals the end of the coaching relationship for this particular journey.

In the first session, the backlog is formed and prioritized and the client chooses the highest priority topic, that is the topic that gives the most value to them in the here and now. The problem moves into a coaching conversation centered around the client achieving the goal of the coaching agreement that formed around the problem topic. Influenced by a key power tool that people managers utilize in their coaching, the coach works with the client to help examine skills and passions that might be applied to the coaching topic. In particular, the gap is explored to see if there is a potential course of action that can help the client achieve the goals of this session. Getting to a point of commitment is the goal of the coaching session, for the client to commit to a course of action that will hopefully solve the original problem and achieve the goals of the coaching agreement. The model may continue in a cycle of skills-passion examination until this point is reached. When commitment is attained, a timebox between sessions is agreed for implementing/practicing exploring the committed action before the next session commences. Upon the next session, a quick review is held between the client and the coach to brie y explore if the committed action was completed and to gain an insight into the improvement journey the client embarked on. If it was agreed upon with the client, this could be an accountability-driven check-in. After the review, the current state and proposed future state are reviewed to see if the learnings and journey between sessions have uncovered new challenges and issues and to verify that the current set of problems within the Backlog is still valid and prioritized accordingly. This can allow for calibration on the future state as we learn by doing and experiencing. The client then selects the next most valuable topic to progress into the coaching agreement for the current session.

This model allows for journeys of mutual understanding, incremental improvement, and for allowing the client to select the most appropriate topic that will help them in the here and now while being cognisant of the overall journey and goals.

Cultural Impact of a Transformation

Culture is key to any change management strategy and is a precursor to helping teams understand the transformation process by enabling some base-level approaches to both communication and transparency. Red Hat has a very strong cultural identity that is intertwined with the Open Source mindset, with Open Source being a culture in and of itself (Vaidhyanathan (2005)). Red Hat, as a multinational, has disparate Engineering teams building out various product lines. The team, like most within the company, are given the autonomy to help form their mission, vision and form their subculture, with the overarching culture of the company acting as guiding light. The company is value-driven, with the key values of Freedom, Courage, Accountability, and Commitment that have to work in balance. To quote the Red Hat culture statement: No single value is as important as all of them. Freedom without accountability is chaos. Courage without commitment is aimless. Commitment without freedom is pointless. Accountability without courage is uninspired. Balancing our values is how we compound innovation and work together harmoniously. Maintaining this balance keeps Red Hat in a state of constant change and also firmly roots us in a greater purpose of constant improvement. The role of the manager is to act as an ambassador for the culture and become an enabler and multiplier of that culture within their teams.

With a high-performance culture, moving the team to a new mode of working has to be done in line with the company and team culture. For the team that transitioned, there exists a sub-culture centric on Open Source values. Open Source, at its heart, values collaboration, transparency, and the notion of a meritocracy. Therefore the map was set in place for any transformation to adhere to, respect, and honor the overriding culture. Throughout the process of recalibrating the team, the ideas and the micro changes to introduce Lean concepts were seeded by the manager and the change agent, who acts as a CI Coach for the team. Before this recalibration, the team have had 18 months of experience working in this manner where they have been empowered to move their process in the direction they wish to work. That is done carefully and deliberately, to ensure lasting change. A menu of options is presented by the coach and others who have experience in this area, but nothing is forced upon them. The team is free to pick and choose how and when they wish to implement changes with a loose direction initially set. Over that period of 18 months, the team warmed up a Scrum-centric approach to developing software. With the introduction of Lean concepts, over the past 12 months, the team has similarly chosen from a menu of changes that could optimize and improve the day-to-day operations within the team. Through raising awareness of potential drawbacks, in the form of waste being generated, the team went about metricizing their workload. The Scrum approach is founded on Empiricism, so the goal of gathering data to make informed decisions was second nature to the team. The team had bi-weekly syncs, where the sub-teams, each working on a standalone initiative that the overall group was responsible for, came together to cross share their knowledge and brainstorm improvements. Over the 12 months, the team removed 7 hours of ceremony-oriented waste from their working week. As the changes were made transparently and with the consent and buy-in of the team, the culture and mindset of the team were not infringed. If anything, the culture enabled both the transformation to succeed at a team and people manager level. The success of the transformation was only possible due to the focus put in initially on forming a process that adhered to the culture and identity of the team. That approach has made for calibration and recalibration with the understanding that if the changes are not successful, that the team tried this in a meritocratic manner and that they have the psychological safety to know that the management team has supported the decision, embraced the failure, and used it as an opportunity to learn from.

High Performing Teams and Future Work

Software Engineering has embraced a way of working that has now shown huge line deficiencies in a remote-centric manner. The new hybrid model of working in a post-Covid-19 world will further magnify that. Managers are natural agents of change, with the ability to influence at the strategic level as well as project, grow and enable at the individual contributor level. The role of the manager needs to consider how engagement and change management can work, particularly in high-performing teams, that are both well established and successful. The literature is sparse on how both engagement and change management differ for high-performing teams or within knowledge workers, of which software engineering teams are a natural nexus point. The contributions in this paper are a first step in establishing insights into this area and future research targeting this particular demographic within the software industry has been identified as a follow-on objective of the authors. With this particular challenge and the old paradigm of software engineering management changing, a rethink on the role of the manager, to move more into a catalyst leader, a role described by Lomenick (2013) as one that energizes and inspires the team in equal measure by placing a focus on the people and projecting the goals, aims, and objectives through the people, in an empowering manner. That needs to be complemented by creating the right culture that allows for a continuous improvement mindset to emerge within the team. Underpinning that culture is the need to look at establishing and reinforcing psychological safety. A novel model for coaching in that environment is presented as an output of this paper. The model, enables managers to coach for high performance and continuous improvement, becoming a focal point for competency development and overall team-wide transformation.

This is a journey of continuous improvement and like most continuous improvement journeys, the destination is rarely reached as it constantly moves. Areas that are of interest for additional future work include looking at applying the coaching model in companies that do not have the cultural support and harnesses that exist in Red Hat. The model could become a mechanism to enable a cultural transformation in and of itself, whereas right now, it’s empowered by the cultural foundations. Inverting that could be powerful for companies that are after having a cultural shift, due to the Covid-19 pandemic changing work practices, locations, and methodologies. Further research is being actively conducted around the re-calibration e orts from Scrum to a more Lean-inspired variant. The team is self-selecting and moving at their own pace. Companies use KPIs and OKRs to metricize and reinforce goals and progression (Parmenter (2019)) and Red Hat is no di er-ent. Applying more stringent KPIs and OKRs to ne tune the Lean process is on the horizon. That change will solidify the improvements made and put more of an emphasis on formally adhering to them. With that level of strictness, there is a danger that the continuous improvement mindset will stagnate and teams will no longer ask the question of why in a knowledge-seeking manner.

References

Ahmed, A., Ahmad, S., Ehsan, N., Mirza, E. & Sheikh, Z. Agile software development: Impact on productivity and quality

Alstrup, L.‘Coaching continuous improvement in small enterprises’, Integrated Manufacturing Systems

Bakker, A. B., Albrecht, S. L. & Leiter, M. P. Key questions regarding work engagement’, European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology

Bamford David, R. & Forrester Paul, L. ‘Managing planned and emergent change within an operations management environment’, Inter-national Journal of Operations & Production Management

Beck, K. ‘Manifesto for agile software development.

Benders, J. & Van Bijsterveld, M. ‘Leaning on lean: the reception of a management fashion in Germany, New Technology, Work and Employment

Bennett, N. & Lemoine, G. J. ‘What vuca means for you’, Harvard business review 92.

Bravata, D. M., Watts, S. A., Keefer, A. L., Madhusudhan, D. K., Taylor, K. T., Clark, D. M., Nelson, R. S., Cokley, K. O. & Hagg, H. K. ‘Prevalence, predictors, and treatment of impostor syndrome: a systematic review’, Journal of General Internal Medicine

Brynjolfsson, E., Horton, J., Ozimek, A., Rock, D., Sharma, G. & TuYe, H.-Y, Covid-19 and remote work: An early look at our data, NBER Working Papers 27344, National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc.

Burrell, D. ‘Exploring leadership coaching as a tool to improve the people management skills of information technology and cybersecurity project managers’, Holistica

Camargo, C. E. The human aspect of lean: Special considerations for an adequate implementation of lean.

Carvalho, B., Henrique, C. & Mello, C. ‘Scrum agile product development method -literature review, analysis, and classification, Product: Management & Development

da Silva, F. Q. B., Franca, C., de Magalh~aes, C. V. C. & Santos, R. E. S. Preliminary findings of the nature of work in software engineering: An exploratory survey, in ‘Proceedings of the 10th ACM/IEEE International Symposium on Empirical Software Engineering and Measurement, ESEM ’16, Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA.

Demerouti, E. & Sanz Vergel, A. ‘Burnout and work engagement: The jd-r approach’, Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior 1.

digital.ai ‘14th annual state of the agile report’.

Edmondson, A. C. The Fearless Organization: Creating Psychological Safety in the Workplace for Learning, Innovation, and Growth, John Wiley & Sons.

Emiliani, M. ‘Origins of lean management in America: The role of Connecticut businesses’, Journal of Management History

Gancarczyk, A. & Gri n, L. ‘Small scale scrum’, Agile Alliance Experience Reports.

Geary, J. F. & Dobbins, A. ‘Teamworking: a new dynamic in the pursuit of management control’, Human Resource Management Journal

Gill, J. & Whittle, S. ‘Management by panacea: Accounting for transience’, Journal of Management Studies

Goksu, M. ‘Comparison of the agile methodologies and the waterfall’.

Griffin, L. Implementing Lean Principles in Scrum to Adapt to Re-mote Work in a Covid-19 Impacted Software Team

Griffiths, K. & Campbell, M. ‘Regulating the regulators: Paving the way for international, evidence-based coaching standards’, International Journal of Evidence-Based Coaching and Mentoring

Grzegorczyk, M., Mariniello, M., Nurski, L. & Schraepen, T, ‘Blend-ing the physical and virtual: a hybrid model for the future of work’, Policy Contribution, Bruegel.

Gunaki, ., Teli, S. & Siddiqui, F, ‘A review paper on productivity improvement by value stream mapping’, Journal of Emerging Technologies and Innovative Research (JETIR) 2, 1119{1124.

Heyden, M., Fourne, S., Koene, B., Werkman, R. & Ansari, S, ‘Re-thinking ’top-down’ and ’bottom-up’ roles of top and middle managers in organizational change: Implications for employee support’, Journal of Management Studies

Ho man, M. & Tadelis, S. ‘People management skills, employee attrition, and manager rewards: An empirical analysis, Journal of Political Economy

Jansson, N. ‘Organizational change as practice: A critical analysis, Journal of Organizational Change Management

Jiang, H., Luo, Y. & Kulemeka, O. ‘Social media engagement as an evaluation barometer: Insights from communication executives’, Public Relations Review

Kalliamvakou, E., Bird, C., Zimmermann, T., Begel, A., Deline, R. & Ger-man, D. ‘What makes a great manager of software engineers?’, IEEE Transactions on Software Engineering PP

Kular, S., Gatenby, M., Rees, C., Soane, E. & Bailey, C. ‘Employee engagement: A literature review’.

Kunos, I. ‘Role of coaching models’, International Journal of Research

Lenberg, P. & Feldt, R. Psychological safety and norm clarity in software engineering teams

Little, B. & Little, P. ‘Employee engagement: Conceptual issues’, Journal of Organizational Culture, Communications and Conflict

Lomenick, B. The Catalyst Leader: 8 Essentials for Becoming a Change Maker, Thomas Nelson Inc.

Mccarthy, G. & Ahrens, J, Challenges of the coaching manager.

Meade, E., O’Kee e, E., Lyons, N., Lynch, D., Yilmaz, M., Gulec, U., O’Connor, R. & Clarke, P. (2019), The Changing Role of the Software Engineer

Mosadeghrad, A. ‘Occupational stress and its consequences’, Leadership in Health Services

Nikitina, N., Kajko-Mattsson, M. & Strale, M. From scrum to scrum-ban: A case study of a process transition, in ‘Proceedings of the International Conference on Software and System Process, ICSSP ’12, IEEE Press, p. 140{149.

Norman, M. & Venter, I. Factors for developing a software industry, pp. 1{10.

Palmquist, S., Lapham, M., Garcia-Miller, S., Chick, T. & Ozkaya, I. ‘Parallel worlds: Agile and waterfall differences and similarities.

Parmenter, D. Key performance indicators (KPI): Developing, implementing, and using winning KPIs, Wiley.

Raman, N., Cao, M., Tsvetkov, Y., Kastner, C. & Vasilescu, B. Stress and burnout in open source: Toward finding, understanding, and mitigating unhealthy interactions, in ‘Proceedings of the ACM/IEEE 42nd International Conference on Software Engineering: New Ideas and Emerg-ing Results’, ICSE-NIER ’20, Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA,

Robinson, D., Perryman, S. & Hayday, S, The drivers of employee engagement.

Robinson, P. T. & Beecham, S, Twins: This work ow is not scrum: Agile process adaptation for open source software projects, in ‘Proceedings of the International Conference on Software and System Processes’, ICSSP ’19, IEEE Press,

Saks, A. & Gruman, J. ‘What do we know about employee engagement?’, Human Resource Development Quarterly 25.

Sanjay, B. & Peter, B. ‘Lean viewed as a philosophy, Journal of Manufacturing Technology Management

Sutherland, J. & Schwaber, K, ‘The scrum guide’

Vaidhyanathan, S. ‘Open source as culture-culture as open source’.

Womack, J., Jones, D. T. & Roos, D. The machine that changed the world: the story of lean production { Toyota's secret weapon in the global car wars that is revolutionizing world industry.