A Coaching Power Tool Created by David Kincaid

(Leadership Coach, UNITED STATES)

The Roller Coaster Ride

As a boy growing up in Tampa, Florida, my family often drove across the state to Orlando, to visit my grandmother. Along the way, we passed the Circus World amusement park with its famous “Roaring Tiger” wood-framed roller coaster. We had been to the park once as a family, but my parents hated roller coasters and so I had been prevented from taking a ride. And so, each time we passed, I dreamed of a day when I could. That day came when I joined a church youth outing to the park.

Within moments after entering the park, I broke away from the group to ride the famous roller coaster. It seemed like hours that I stood in the line that cloudy Saturday and watched as one car after another clicked and clacked its way to the pinnacle and then with a shriek that could be heard far below, the passengers were hurtled down the other side. With each passing car my excitement, and my anxiety, rose. Soon, I felt butterflies stirring in my belly, while a sense of dread came over me. Even my muscles and jaw became tense! How I could feel such intense sensations simply by standing in line?!

Soon enough, I was neatly seated in the front car of the train; I had waited for an extra round just to secure that place. With a lurch, I was off! Each click of the wheels seemed like a clock ticking down to that dreaded moment when I would reach the top. I could feel the strain of the engines pull the cars ever higher towards the mighty pinnacle. Up and up and up we went. As I sat back in my seat, the track itself disappeared and all I could see was the open sky. Then the train slowed and ever so gently tilted over the top to reveal what seemed a terrible length of track headed straight for the ground! With a mighty thrust, I was hurdled down the hill while every muscle in my body strained against the sensation. I gritted my teeth, tears streamed from my eyes, my stomach churned and I longed for it all to be over quickly.

What happened next was entirely unforeseen. Something inside me said to let go. So, I gulped a big breath of air, released my hands from the rail in front of me, relaxed all my muscles, and screamed at the top of my lungs. “AHHHHHH!”At that moment, a sensation of warmth, of peace, spread across my body. Suddenly, I experienced joy. The laughter replaced screaming. Shouting replaced dread. Handwaving replaced gripping. For the next three and a half minutes, on a runaway train on an old rickety track, I experienced ecstasy.

In my simple, little boy way, I had discovered a tool that it would be years before I learned to utilize. I learned to transform the agony of resistance into the joy of acceptance.

The Nature of Resistance

What is this resistance so many of us experience? When we resist, we seek to avoid the negative impact of some action or we attempt to prevent some anticipated negative outcomes from occurring. Something is acting upon us and we choose to deny or thwart the force or effect of that event. The event or action is the object of our resistance. And, to resist, we employ a tool.

To better understand this relationship, let us consider the example of rain. Droplets of the waterfall from the sky and many of us recoil. We do not like it. We raise an umbrella, don our raincoats or simply run for shelter to avoid the effect of the action—the rain. The tool of resistance is the umbrella, the raincoat, the shelter. In another sense, we are the tool of resistance. Let’s say it’s raining and you are inside, but today you had planned to go for a run. Perhaps you grumble as you look out the window, “damn rain always gets in the way!” What is the object of resistance? The rain. But, what is the tool with which we resist? It is the idea or the thought. In short, it is the expectation, that it not rain.

But wait, do you notice something about these two scenarios? In neither case does the act of resisting change the circumstance. It continues to rain. And, yet, a sense of struggle emerges that is wholly our own. A feeling of suffering creeps into our experience. We may find ourselves disgruntled or irritated, or even thwarted in our intentions. Yet, the undesirable thing continues. It persists. The thing that we resist is our desire for it to be some other way. As long as we are fixated on the way things should be, we will be at odds with the way things are.

Reflection

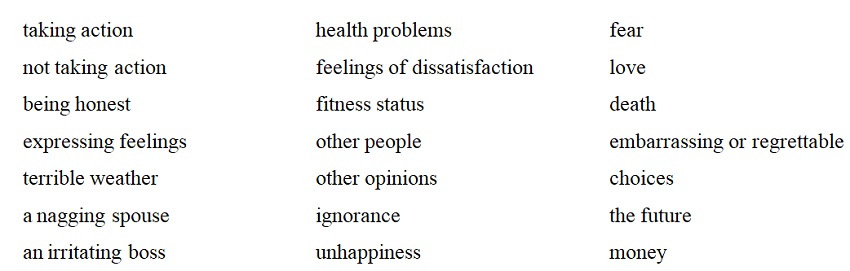

Human beings resist a great many things:

ACTIVITY: Take a moment to reflect on the list above. Then respond to the following:

- What things in your own life do you resist?

- For each item, you resist, ask yourself, what is it about that thing that motivates you to deny its existence or attempt to prevent its happening? Is it fear? Disappointment? Losing? Thwarted intentions? Being seen as you are? Change? What is it you wish were or were not so?

- How effective is this strategy of resistance for achieving your desired outcome?

The Role of Acceptance

Acceptance is the state of acknowledging what IS. It is not about permitting harmful behaviors. Instead, it is an acknowledgment, or recognition, of what IS in the world around us. When we accept that it is raining, we are not giving the sky permission to rain upon us. No. We are simply acknowledging a condition. In the case of rain, we may not desire that condition, but that does not change its occurrence.

Always say “yes” to the present moment. What could be more futile, more insane, than to create inner resistance to what already is? What could be more insane than to oppose life itself, which is now and always now?” —Eckhart Tolle, “The Power Of Now”

There are many spiritual leaders today, as well as indications in all forms of religious philosophy that have pointed to this state of acceptance as fundamental to happiness. There are practical implications as well. When we spend our energy resisting what is so, we misplace our efforts. Rarely is the solution to stop what is happening. Often this is impossible. Can you change today how your weight, your fitness level, the amount of money in your bank account, the fact that your marriage has ended, or that you’ve been fired? What then? What occurrence or reality should replace that which we wish to impede? When we accept what IS, we are free to discover a new path forward. This is the domain of creativity and innovation. Solutions to the challenges around us begin to emerge. By accepting what is happening, we move closer to an objective view of the situation. Our minds are then free to consider what is most important and to generate a response that is in keeping with what we want to achieve rather than focusing on what is wrong with the situation.

Consider again the example of the runner who is thwarted by rain. Have you ever had a client like this—someone who has fitness goals but is prevented from achieving them by external circumstances? How does their resistance of those undesirable external forces improve the situation? What if they were to acknowledge the actuality, the present state, of the situation? There is, then, a greater openness to explore what is important about running and begin to look for solutions outside of the one that was thwarted by the falling rain. For example, you could wear rain gear and still run outside. Or, the runner could find an indoor track or treadmill on which to run. Or, simply, postpone until after the rain or some other day. Although the outcome—that it is raining—is not altered, there is a different quality of experience that is available to the runner. The runner is now available to experience fulfillment independent of weather as an external force.

Coaching Application

Working with clients to identify their areas of resistance and then facilitating their move to acceptance can be challenging. Often, resistance veils itself in an almost dogmatic belief that the opposition is real. The runner may sincerely believe it is the rain or the weather that is hindering him or her from going outside.

There are a great many resources available today to assist coaches and clients move from resistance to acceptance. Much can be learned from the therapeutic sciences. Stephen B. Hayes originally developed the concept of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) in 1986 and primarily focused his attention on the ways that language and thought to influence our internal experience.

An example of this is my opening story about The Roller coaster Ride. It was the thoughts about potential suffering that influenced my physical and emotional state as I stood in line. The ride is designed to toy with this apprehension. Although there is a possibility that something could go wrong, the statistical likelihood of it happening is incredibly minute. This fact, however, is not enough to assuage the feelings of anxiety. The muscle tension and stomach butterflies are driven by thoughts about what might happen and are not based on any experience. So, too, it is for our clients. Presenting clients with logic or facts is an ineffective tool for countering resistance.

Techniques For Identifying Resistance

An astute coach will listen to the client and identify language that indicates resistance. Consider the statement: “I would have gone for a run, but I was prevented from doing so by the rain.” At first, this seems perfectly reasonable. Upon further reflection, this statement contains an underlying belief, which is that the rain—or the weather—has the power to inhibit action. Perhaps this is the case if there were a tornado or tsunami. Generally speaking, a runner is not hindered from running by such extreme forces of nature, but rather by the idea that one might become wet in the process. It is the experience of being wet or pelted by raindrops that are undesirable. The rain, itself, has no real power over the runner’s decision to go or to remain inside.

Utilizing Powerful Questioning can also help to uncover where there is resistance. “Meaning” is a particularly influential aspect of resistance. We often assign meaning to the hindrances that we face in accomplishing our goals. Here are a few examples of such questions:

Techniques For Developing Acceptance

Dr. Rich Blonna has produced a significant volume of work on Acceptance and Commitment Coaching (ACC), which is based on the psychotherapy work of Dr. Hayes. Blonna’s work addresses six core processes for assisting clients to become more psychologically flexible. One of these is the Lack of Clarity of Values. Coaches can explore what it is that the client values about the desired outcome? This can be a useful way of shifting the client’s focus away from the obstacle and return their focus to the goal. By doing so, the client can come to accept the present conditions and focus on solutions that bring them closer to the outcome, rather than generate negative emotions around the hindrance.

Coaches may also find success in engaging clients in a self-guided meditation exercise. This exercise is especially useful when clients find themselves resisting negative emotions or avoiding potentially negative outcomes along their journey towards a goal.

Exercise: The Undesired Guest

A client is invited to visualize the object of their resistance—the undesirable emotion or possible outcome—as a person knocking aggressively knocking on the door to their home. The client is then asked to imagine that they open the door and invite The Undesired Guest to come inside and sit down next to them. Clients can then return their focus to their goal while allowing The Undesired Guest to remain seated next to them. Clients should seek to remain in the meditative state for 10-15 minutes, simply allowing The Undesired Guest to remain nearby.

Throughout the meditation or visualization, the client should notice what their experience was like when they first observed the aggressive knocking at the door. What was it like to invite the anxiety or fear or undesirable outcome into their home; their inner space? When the client refocused on their goal, what was The Undesired Guest doing? What did the client notice about The Undesired Guest after some minutes had gone by? Finally, how can this learning be used to reinvigorate their movement towards their stated goal?

One of the by-products of this meditation is that clients begin to recognize the object of their resistance as nothing more than undesirable thoughts and emotions. Clients can begin to identify what is real about the situation and return their focus to solution-oriented thinking. They may find themselves experiencing elevated levels of anxiety as The Undesired Guest enters their inner space, but may quickly find that those feelings subside as they become accustomed to the powerlessness of The Undesired Guest to affect any real action.

Conclusion

You may have heard the expression “What you resist, persists.” How true. While it is understandable that humans would wish to suppress negative thoughts and emotions and avoid undesired outcomes, resistance is often the very thing that perpetuates their existence. When clients become aware of what they resist and allow acceptance of what IS, they free themselves to experience creativity and joy in the face of adversity.

Resources

Antiss, T., Courtney E. Ackerman, MSc., (2020). How Does Acceptance And Commitment Therapy (ACT) Work?

Blonna, R. (2014). Acceptance and Commitment Coaching. In the Passmore, J. Ed. (2014). Mastery in Coaching: A Complete Psychological Toolkit for Advanced Coaching. London: Kogan Page Publishing.

Harris, R. (2011). Embracing your demons: An overview of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy. Psychotherapy.

Kincaid, David (2020). Meditation: The Undesired Guest. The full-length format is available upon request.