Research Paper By Michelle Jewell

Research Paper By Michelle Jewell

(Business Coach, UNITED STATES)

Your beliefs become your thoughts, Your thoughts become your words, Your words become your actions, Your actions become your habits, Your habits become your values, Your values become your destiny. ― Gandhi

That big question: Why…

Why do I feel more empowered or motivated when I have a balance of structure and creativity while someone else can only create in a world where there are no rules or structure? And why does another person only find motivation when there is a rigid structure providing them with a sense of security? Is one person right, and everyone else wrong? Why does it even mean to be right?

For hundreds of years, sociologists and philosophers have wrestled with these same questions and have developed many theories on values and valuation that help shape our understanding today. This is a rich and complex topic, yet one that is extremely powerful, especially as a coach.

In my exploration of my own values and ways to help connect clients to their values I came across interesting tools and resources based on the Schwartz Theory of Basic Values prompting my further investigation of the theory.

Shalom Schwartz is a social psychologist who has over 200 papers published on the topic of values, with more in the works. He is a leader in the field of Values but not nearly as well known as he should be. An Overview of the Schwartz Theory of Basic Values (Schwartz, 2012) is a great starting paper to begin building an understanding of his work, however, it is still a more complex scientific article.

What follows is an overview of Schwartz’ paper which will give you a more detailed understanding of what values are, the core set of values and how they relate to each other, the science that helped get a more universal understanding of values and how values are distinct from attitudes, beliefs, norms, and traits. Through a deeper appreciation of the Schwartz Theory of Basic Values, my hope is that coaches, as well as those exploring their own values, will have a more concrete understanding to base their exploration on.

The Schwartz Theory of Basic Values: An Intro

The Schwartz Theory of Basic Values presents a set of 10 values universal across all cultures and helps to explain where they come from. It is based on the concept that the values form a circular structure based on the motivations each value expresses, which helps articulate how some values are more similar while others are more diametrically opposed.

Up until the time of this research, the major challenge faced when applying the concept of values in social sciences was the fact there was no shared definition of what basic values were or any valid ways to measure values. The research by Schwartz et all provided exactly that.

It is important to note that although the research specifically talked about the universal nature of these basic values and the structure in how they relate to each other, individuals have very different levels of importance they place on certain values. Every person holds a certain set of values that could be very different from others around them.

Schwartz claims that there are six main features of all values, a claim shared by many others.

As far as the universalism of values, this is likely due to the fact that all of the values are rooted in at least one of the three universal requirements of human existence:

Individuals need to have certain goals that help them cope with human existence, to meet these requirements. Additionally, they need a way to communicate with others about their goals which allows for more group cooperation. Values are the concepts that can represent these goals and help provide language to express them both to yourself and to others.

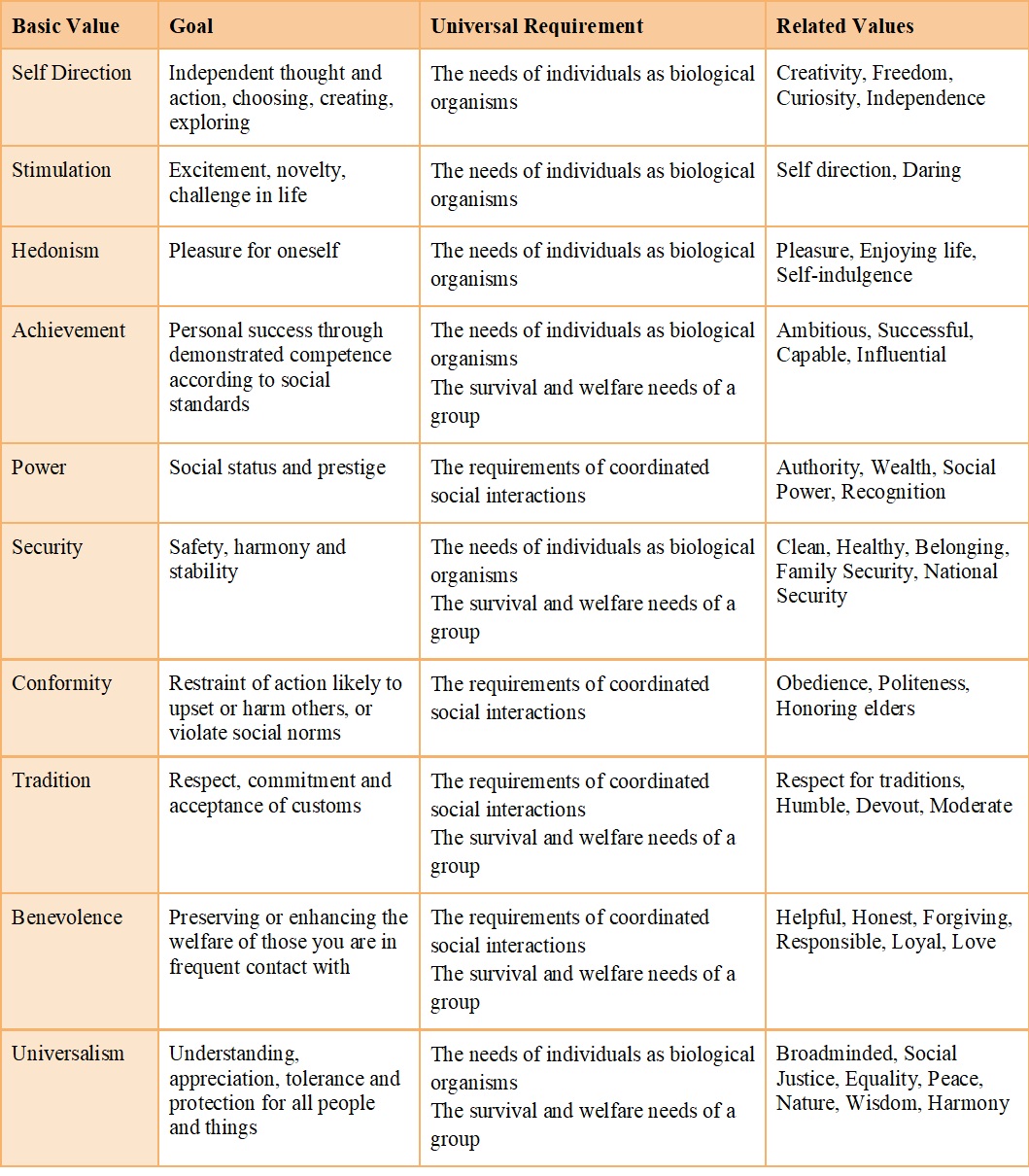

What are these core values?

There are 10 core values. For each value, Schwartz notes what the broad goal is that the value expresses, what universal requirement it relates to and other related values.

The Circular Structure of Basic Values

All of the 10 basic values are related to each other. The behaviors that result from any of these values in action have consequences that potentially conflict with another value, or are similar to another value. These interactions brought about the circular structure that is at the core of the Schwartz theory.

A few notes on the model. Values that are next to each other are considered more similar. It is likely the behaviors that result from these values are, in at least some ways, complementary or related. Values that are opposite each other on the other hand, are more conflicting. For example, the behaviors resulting from the values of Power and Universalism are things that could be in direct conflict with each other.

Tradition and Conformity are shown in the same wedge as they share extremely close motivational goals, a focus on socially imposed expectations over the self. In the case of Tradition, those social expectations are more abstract such as religion or cultural customs, whereas, with Conformity, the social expectations are from others around you interact with such as teachers, parents or bosses. Since Hedonism is the opposing value in this model, it suggests that Tradition conflicts more strongly with Hedonism than Conformity does.

Grouping values into themes as we move around the circle let us look at the broad conflicts that this model presents:

Most of the 10 values fall into one of those 4 themes as shown by the axis’, however, Hedonism is the only outlier as it shares some characteristics of Openness to Change as well as Self Enhancement.

This circular structure suggests that although there are 10 explicit values, values are more like a continuum, where there are some shared motivations between adjacent values. This high level of integration clearly illustrates that the actions, behaviors, traits, and norms displayed by individuals and groups are a result of an integrated set of values, as opposed to clear and distinct values.

There are other variations of the model that exist allowing for deeper exploration of how these values are alike or opposite each other. The value of this and other models is that once your personal hierarchy of values is better understood, you can look for patterns to see if your values indicate a tendency toward social or personal focus, or anxiety avoidant or anxiety-free focus.

How are Values Measured?

At this point, you may be wondering how Schwartz was able to determine these values and the universality of values. There are two primary research tools used that allowed him to collect data in over 82 countries to prove the universal nature of this model.

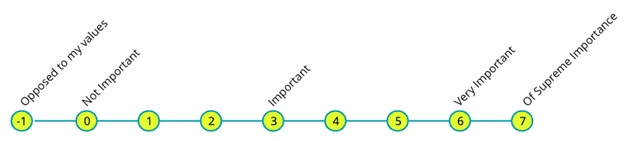

The first is the Schwartz Value Survey. This is a text-based survey where participants are asked to review two lists of value items and rate the importance of each value based on a 9 point scale. The first list is 30 nouns, and the second is 27 adjectives all defining potentially desirable ways of being or acting, related to the motivational goals of the 10 values.

For example, participants may see “EQUALITY (equal opportunity for all)” as a measure of Universalism, or “PLEASURE (gratification of desires)” as a measure of Hedonism. Across both lists, there are anywhere from 3 to 8 value items representing each of the 10 basic values, based on the conceptual breadth of the value. Some values such as Universalism have much more context to them than others like Hedonism.

The rating scale is a 9 point scale to rate the importance of each list item in terms of how it related as a personal guiding principle for the respondent.

This scale it intentionally non-symmetrical with more response options on the important side based on the bias the researchers learned people tend to have when thinking about values based on pre-tests.

The other test used to measure values is the Portrait Values Questionnaire (PVQ).

This is a verbal method where participants are given verbal portraits of 40 different people, describing their goals, aspirations or wishes. Each portrait was designed to represent a specific value. For example, a portrait for Self Direction may sound like “Thinking up new ideas and being creative is important to him. He likes to do things in an original way”. The focus on goals was to help avoid some of the confusion that can arise if describing someone’s traits. Although there can be lots of similarities between traits and values, just because someone expresses a certain trait – creativity for example – does not mean they also share that value – Self Direction in this case. Exactly the same as the survey, there are anywhere from 3 to 8 portraits representing a single value.

Participants are asked to compare each portrait to themselves answering how much like you that person is. The directionality of this comparison is important. By asking people to compare others to yourself, it focused the attention on just the facts of the portrait that were shared which allows the assessment to really focus on values.

In both cases, the measurement tools are used to measure an individual’s value priorities which looks at how the values stack in relative importance as opposed to how high or low they score on the scales. This is because everyone will have their own tendencies in how they use rating scales, but regardless of scores, what drives behaviors and actions is how the values relate to each other on that hierarchy.

Interestingly, while there is a lot of variance of value importance at the individual level when zooming out to the society level, there is a lot of alignment. The values of Benevolence, Universalism, and Self-Direction are consistently at the top, while power and Stimulation values are lowest ranked. This is most likely due to the fact that values help to maintain societies, and regardless of where in the world you are there are some common requirements for positive societal function:

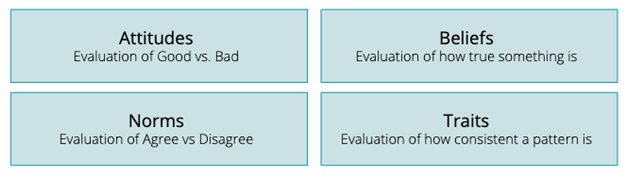

How are Values different from Attitudes, Behaviors, Traits, and Norms?

The last section of the paper takes a deeper look at how Values are different from Attitudes, Behaviors, Traits, and Norms – commonly interchanged ideas. Schwartz proposes that while all of these things help us infer why someone acts the way they do, what differentiates them from each other is in how they are measured.

Values are closely related to all of these ideas and can influence them, but Schwartz argues that Values are a distinctly different thing. As an example, someone who has a value of Stimulation would likely have a positive attitude about sky diving, while someone who has a value of Security would have the opposite attitude.

Traits are often most confused with value as they can be described with the same words as described earlier with the Creativity example.

To sum it all up…

Schwartz’ Theory of Basic Values lays out a series of 10 basic values, arranged in a circular structure to better understand how they are related or opposed to each other. His extensive research has proved through the use of two different testing methods, that these are universally common values, yet recognizes that the relative importance for an individual can and will vary from person to person.

Values and coaching…

A better understanding of this theory can not only allow you to better understand your own values hierarchy but can allow you to support your clients in exploring their own values. A deeper awareness of values brings new insight into why certain situations can feel triggering, and others can feel rewarding and can give great insight into how you make decisions, placing a significant power back in your hands.

As coaches, it is important for us to bring that understanding of values into our coaching conversations. From a self-perspective, it will allow us to better identify topics or situations that may trigger us so that we can manage to remain in a place of appreciation and non-judgment. From a client perspective, it will allow us to give our clients better understanding and some frameworks to understand their own values and in turn, their behaviors.

I sincerely hope that through this paper, you feel you have a new understanding of the Schwartz Theory of Basic Values and are inspired to bring more value awareness into your coaching practice and maybe even venture into reading more of Soloman Schwartz’s work.

References:

Schwartz, Soloman (2012). An Overview of the Theory of Basic Values. Online Readings in Psychology and Culture 2(1). https://doi.org/10.9707/2307-0919.1116