Research Paper By Joanne Lee

(Health and Leadership Coach, AUSTRALIA)

If you feed a man a fish he can eat for a day; teach him how to fish and he can eat for life.

…Coaching teaches patients to fish. (Amireh Ghorob 2013)

Introduction

People with a chronic disease – such as heart disease, stroke, cancer, diabetes and kidney disease – live with a life-long condition that causes significant life changes and limits to their mobility and independence. As people develop two or more chronic conditions (complex chronic disease), their care becomes disproportionately more complex and difficult for them to self-manage, or the health and social care system, to manage. These chronic conditions reduce quality of life, increase disability, increase morbidity and increase mortality (1).

Chronic diseases have overtaken infectious diseases as the leading causes of death and disability accounting for 60% of all deaths globally (2). In the United States, about half of all adults suffer from at least one chronic disease, with a quarter of all adults suffering from two or more chronic health conditions. As the population ages, multiple chronic conditions will affect three quarter of adults 65 years and older. These diseases are responsible for 7 out of 10 deaths among Americans each year. Chronic diseases and conditions are also costly to treat, accounting for 86% of the US $2.7 trillion in annual health expenditures (3). By 2020, this is projected to reach US $4.6 trillion (4).

Most experts agree that fundamental improvements in healthcare economics and health outcomes relies on:

- Shifting the health system model from a fee-for-service to a valued-based, patient outcomes model with compensation for improvement in health outcomes;

- Reducing consumption of medical care by improving health; and

- Increasing individual’s focus on and accountability for their health and healthcare costs (5).

This focus on greater individual accountability and the need to adopt a healthier lifestyle has stimulated the growth of the health coaching industry, particularly over the last ten years. The purpose of this paper is to explore the role of health coaching to improve chronic disease management.

Evidence for Health Coaching

A growing body of evidence shows health coaches can motivate individuals to change the behaviours that create health risks – key drivers of costs – as well as help them to better self-manage their chronic health conditions (6-8). Better health outcomes – lower risk for heart disease, stroke and diabetes – and positive lifestyle modifications – blood pressure control, weight loss, increased physical activity and improved physical and mental health status – have been reported. Health coaching also supports long-lasting behaviour changes and reduces hospital re-admissions and length of hospital stays (8). An estimated outpatient and total cost savings of US $286 and US $412 per person per month respectively may be achieved using health coaching interventions (9).

Definition of Health Coaching

In attempting to define what health coaching is, one finds there is no standard definition; however, a recent systematic review provided a well-founded, clear, and concise definition of health coaching (also known as “health and wellness coaching”) by examining the related literature. In 2013, Wolever et al. (10) defined health coaching as:

a patient-centered approach wherein patients at least partially determine their goals, use self-discovery or active learning processes together with content education to work toward their goals, and self-monitor behaviors to increase accountability, all within the context of an interpersonal relationship with a coach.

The health coach is a professional trained in evidence-based behavior change theory, motivational strategies and processes, healthy lifestyle knowledge, and powerful communication techniques that assist patients to develop intrinsic motivation and obtain skills to create sustainable change for improved health and well-being (10).

Health coaching draws on principles derived from psychological and behavioral theories and techniques that focus on behavior change (like motivational interviewing, goal setting and accountability). Similar to other forms of coaching, it is built on the assertion that people have innate wisdom, strength, and creativity that, when skilfully recruited, will guide them to health more efficiently than will external advice (11). The key distinction between health coaching in chronic disease care and other forms of coaching is in its exclusivity of highly vulnerable patients with medical issues and its regard to health and well-being.

Overall, the goal of health coaching in chronic disease care is to improve quality of life and reduce avoidable medical care costs by improving health. This is attained by empowering individuals to achieve self-determined health goals and supporting them to better self-manage the symptoms related to their chronic disease and the lifestyle risk factors.

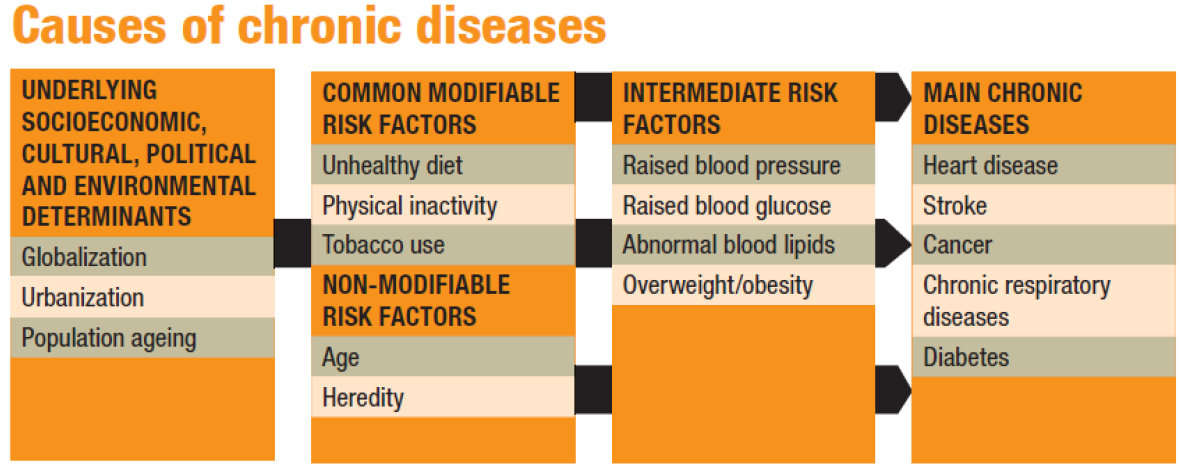

Chronic Disease is within an Individual’s Ability to Control

Although chronic diseases are among the most common and costly of all health problems, they are also among the most preventable. Four modifiable health risk behaviours— notably physical inactivity or lack of exercise, unhealthy diet, tobacco use and drinking too much alcohol – are responsible for most of the main chronic diseases (Figure 1). The World Health Organization has estimated that if the major risk factors for chronic disease were eliminated, at least 80% of all heart disease, stroke, and type 2 diabetes, and more than 40% of cancer would be prevented (12).

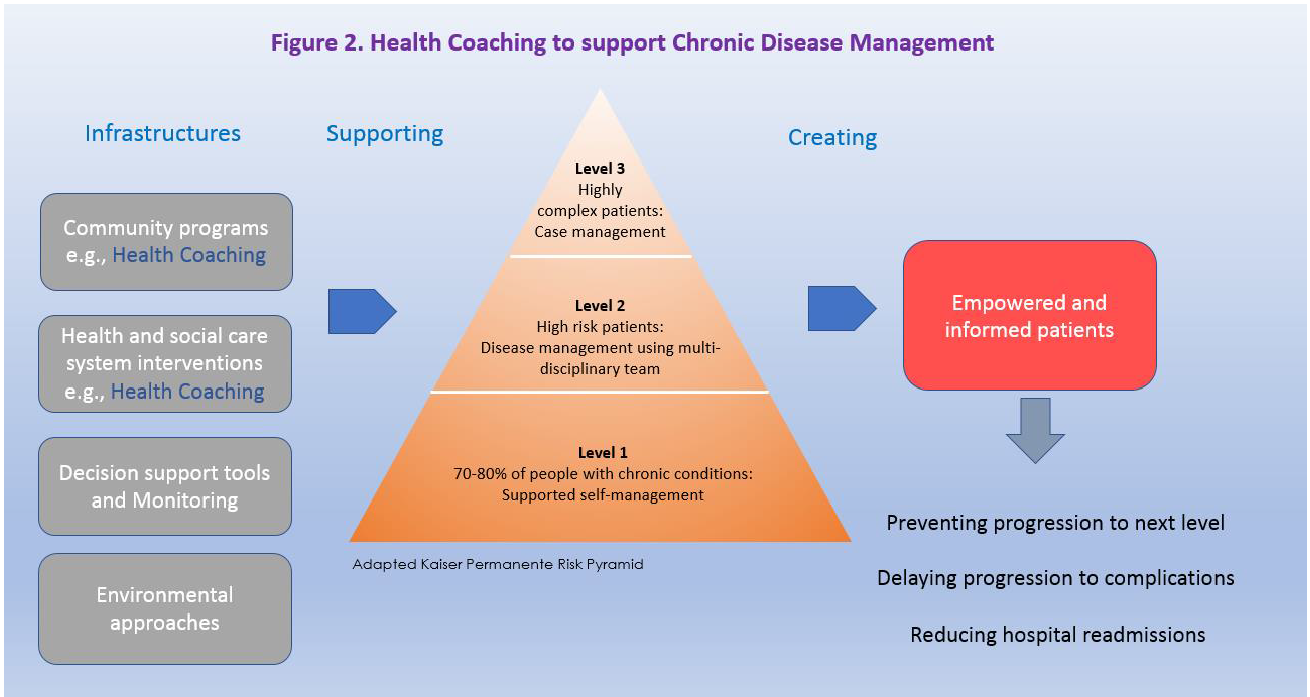

By choosing healthy behaviors people can reduce their chance of getting a chronic disease, or improve their health and quality of life if they already have a chronic disease. With the right support many people with a chronic disease can learn to be active participants in their own care, living with and managing their conditions. This can help them to improve their quality of life, prevent complications, slow down deterioration, and reduce the need for more health care. The majority of people with chronic conditions fall into this category (Level 1, Figure 2) so even small improvements can have a huge impact (14).

Figure 1. Partial screen shot, source: http://www.who.int/chp/chronic_disease_report/part2.pdf. (13)

Figure 1. Partial screen shot, source: http://www.who.int/chp/chronic_disease_report/part2.pdf. (13)

Equally important is the fact that much of chronic illness care is self-managed: every day, these people must by themselves make a myriad of health decisions that can have a tremendous impact on their outcomes and quality of life. Because of this, the patient must take an active role in his or her own health care. A health coach can help these patients by:

These benefits extend to all patients regardless of their risk level (Figure 2); the main difference is, as patients become more complex in their health care needs, the coaching model also changes to reflect the increasing support required (14).

Individual accountability alone though is not sufficient to achieve sufficient scalability. Chronic disease must also be addressed at the population level by creating infrastructure that can further support patients. These include surveillance, policies, supportive environments, healthcare system interventions and community programs (16). One public health strategy for coordinating chronic disease prevention efforts is to encourage a broader range of health professionals in delivering care in the healthcare system, and in community programs to help ensure patients have access to the resources they need to manage their own health. And health professionals skilled at health coaching must be an integral component as illustrated in Figure 2.

Health coaches can act as the advocate that patients and providers need to help empower patients to gain the knowledge, skills, confidence and motivation to become active participants in their own care so that they can reach their self-identified health goals.

Health Coaching fills an Unmet Need in Healthcare Service

Patients with chronic diseases often lack a sense of authority and motivation to participate in their own care at the level necessary for sustained health. Not only that, the goals of chronically ill patients often diverge from those of their health care providers; patients often feel misunderstood and trapped between their effort to obtain appropriate medical care and a desire to live a normal life (17). This phenomenon is known as low “patient activation”.

Why is patient activation important? Because patient activation predicts behaviour i.e., level of “patient engagement”. Higher activated individuals are more likely to engage in positive health behaviours – like adhering to medications – and to have better outcomes (18). “Patient activation” refers to a patient’s knowledge, skills, confidence and motivation to manage his or her own health and care. “Patient engagement” is a broader concept that combines patient activation with the behaviours individuals must master to benefit optimally from the healthcare services (11).

In the case of chronically ill patients:

This “low patient activation and engagement” stems from internal and external barriers such as: low awareness of risk, limited perspectives on possible improvements, lack of confidence and knowledge, lack of skills, distrust of doctors, values conflicts, competing commitments, social norms, cultural norms, and/or environmental obstacles at home or work (11).

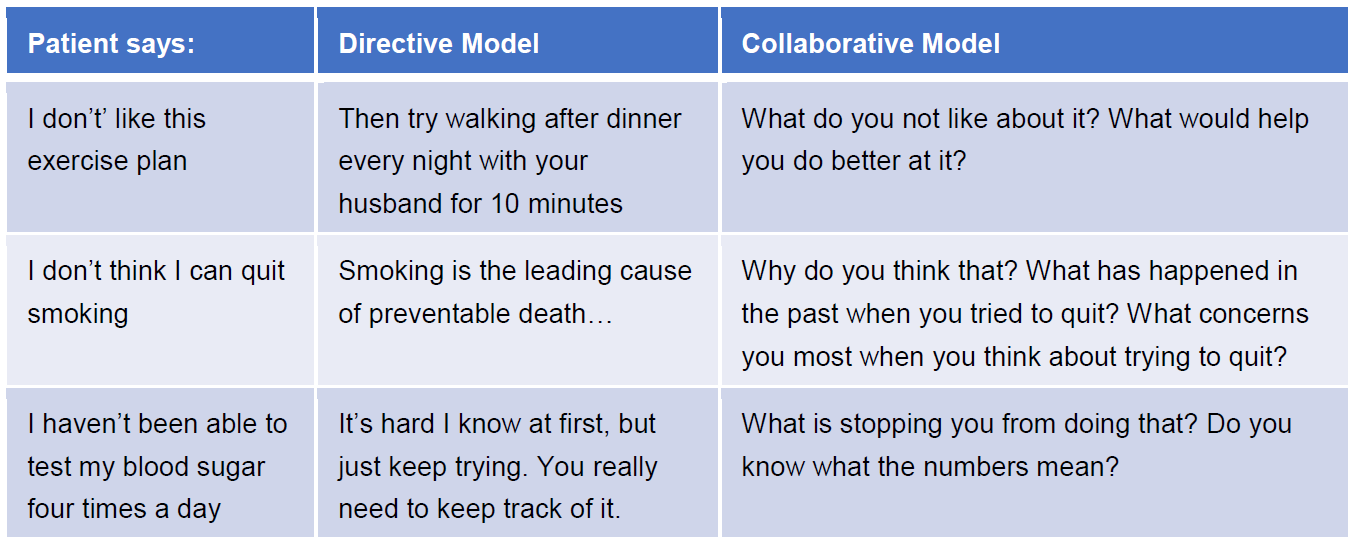

Our conventional healthcare model of care is not always designed with the patient in mind. Rather, it is based on a “directive” approach that is expert-driven, authoritarian, and advice-giving – the patient is seen as the passive recipient of care. Healthcare professionals who operate on this conventional model do not necessarily value patient empowerment, may not use language that can be easily understood by the patient, may not have exposure to or adequate training in the science of behavioral change, and may not have the necessary time or the complex interpersonal skills to facilitate behavior change effectively (11, 15).

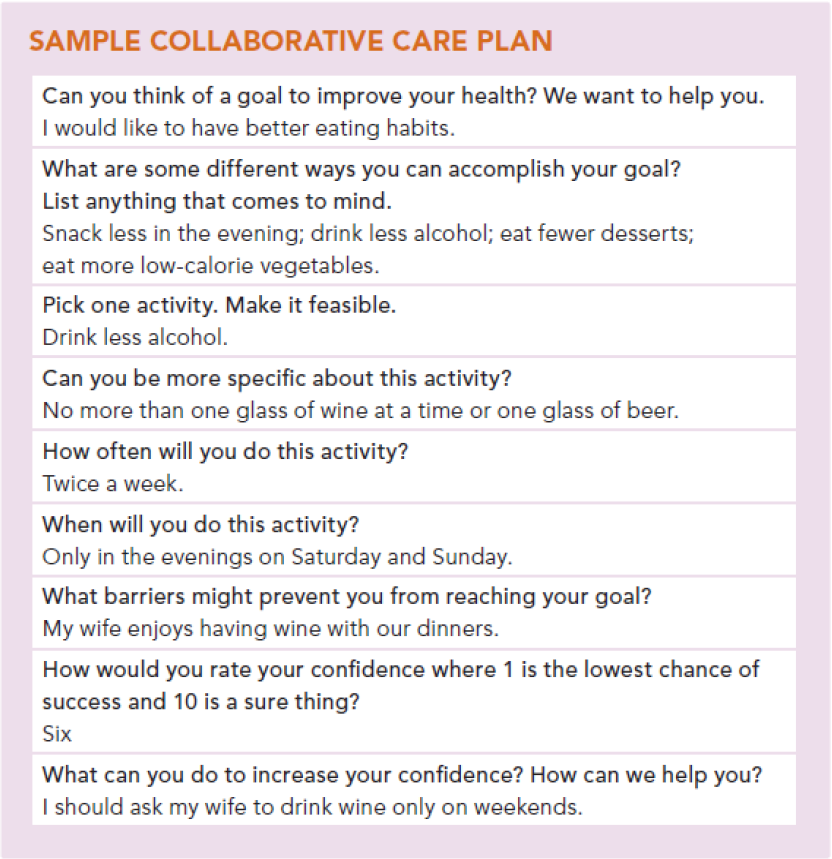

Effective chronic illness care requires a care team with the patient at the center, and the patient to be actively involved in his or her own health care (15, 22). This is commonly known as “collaborative” or “patient-centered” models of care. Studies show collaborative goal-setting and patient-determined goals are effective at enhancing diabetes self-management (23) and reducing health risks (24).

Equally important is empowering individuals to take responsibility for their own health (25). Taken together, a shift toward patient-centricity and a collaborative model so that care teams and patients pursue an active partnership is the solution (Tables 1 and 2). This creates a recognition of the patient’s authority over his or her illness; and in doing so, patients are viewed as experts about their own health, values and lifestyle and doctors are viewed as experts about treatment options and potential risks and benefits.

Table 1. Directive model vs Collaborative model. Adapted from http://www.aafp.org/fpm/2000/0300/p47.html (26)

A skilled individual that is able to facilitate patient activation and engagement is missing in our healthcare model of care. Health coaching is one way to fill this unmet need: “if there is one fundamental principle of health coaching, it is collaborative decision-making with patients” (27).

Table 2. Screen shot, source: http://www.aafp.org/fpm/2013/0500/p35.pdf (22)

Looking to the Future

A key challenge facing the field of health coaching is the lack of consensus in the definition and operationalization of health coaching. As a consequence, wide variations in training, methodology, coaching process and scope of practice exist. Professionalizing the field will require standardisation of definition and training essential to the practice of health and well-being. There are two important reasons for this:

Effectiveness Research: Health coaching is rapidly emerging as a methodology and adjunct treatment for lifestyle diseases (28). The foundational lack of consistency of the health coaching definition means that a rigorous evidence base is lacking, and literature that exists on the subject is vulnerable to misinterpretation. With a consensus definition now available, it is possible to assess effectiveness, and the components of coaching that are necessary to affect behavioural change and health outcomes, and the context in which they occur. As an example, a systematic review of 150 related literature was recently published (2017) using the definition provided by Wolver et al (10) which reaffirmed health coaching to be a promising clinical intervention for chronic diseases (28).

Operationalizing Health Coaching: Health coaching is also rapidly emerging as a role and profession, in diverse health care, employee wellness and community setting (28). As the profession advances, the need for national standardisation reduces the confusion in the healthcare field and public around the role, tasks, background and training of competent coaches. Everyone gains a benefit because adherence to such standards leads to consistently applied practices and enhances the protection of the health and well-being of patients. And to that point, in the United States, a national board certification for health and wellness coaches was launched in 2017 by the International Consortium for Health & Wellness Coaching in partnership with the National Board of Medical Examiners (29). Similar initiatives must be implemented in other countries in order to move the health coaching field forward.

Conclusion

Health coaching improves health behaviour, self-efficacy, and health status in patients with chronic conditions. Health coaches act as the advocate that patients and providers need to help empower individuals to gain the knowledge, skills, confidence and motivation to become active participants in their own care so that they can reach their self-identified health goals. With a uniform definition of health coaching now provided, rigorous research methodology can ensue to accumulate evidence of its effectiveness in reducing the burden of chronic disease, and the components of coaching necessary for its success which will inform training designs and best practices.

References:

1. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2924996/

2. http://www.who.int/whr/2002/en/

3.

4.

5. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3833544/

6. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmedhealth/PMH0076525/

7. http://www.publish.csiro.au/ah/AH13005 8. http://www.thecoachprogram.com/evidence-based/

9. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25588134

10. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3833550/

11. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3833534

12. http://www.who.int/chp/chronic_disease_report/full_report.pdf

13. http://www.who.int/chp/chronic_disease_report/part2.pdf.

14.

15.

16.

17. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16344631

18. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1955271/

19. http://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/192233

20. http://www.annualreviews.org/doi/pdf/10.1146/annurev.pu.10.050189.001115

21. http://www.ub.edu/farmaciaclinica/projectes/webquest/WQ1/docs/osterberg.pdf

22. http://www.aafp.org/fpm/2013/0500/p35.html

23. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1449392/

24. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3850489

25. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17664299

26. http://www.aafp.org/fpm/2000/0300/p47.html

27. http://www.aafp.org/fpm/2013/0500/p40.html 28. http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/1559827617708562

29. http://ichwc.org/