Research Paper By Hedvig Berry Wibskov

(Confidence Coach, CHINA)

Terminology created for this report:

MCAC is the multi-culturally aware coach

Thesis:

The multi-culturally aware coach (MCAC) acquires highly valuable skills. Understanding cross-cultural communication benefits coaching in general.

Introduction During my first days of working in the UN, one of my close colleagues, an Indian man named Rajkumar, taught me an important lesson in cross-cultural communication and how quickly and innocently misunderstandings can arise. In my usual, chipper, Midwest greeting, I had passed Rajkumar in the hallway and exclaimed with a smile, ‘Well, hi there!’ Obviously very upset and hurt, Rajkumar burst out, ‘Who is There? Why do you call me that? You know my name! Why must you always address me as There as if there is no person!’ I was stunned. I didn’t even know what Rajkumar was referring to at first. How could something so innocent be so offensive? But Rajkumar was shaking with anger saying, ‘Every morning, you do not say my name. My name is very special to me!’ There was nothing to do, but for me to apologize profusely and insist that this was my way of being friendly, that I meant no offense. The others in my department heard the story and laughed a bit. Their message was clear, ‘Welcome to the UN: you need to be extra careful in your communication skills.’ It is a lesson that stuck with me.

By way of background, I am Danish-American, raised in Missouri, USA, married to a Danish diplomat, raising four kids in Beijing, China. Before coming to Beijing, I was a project manager for the World Health Organization, working with people from all over the world, all across Europe. Is it any wonder I am now a coach-in-training with ICA?

ICA is an incubator for cross cultural coaching by its very nature. Each and every one of us have said ‘yes,’ to a training program whereby our classmates and instructors are physically as far apart as they can possibly be. And yet, the philosophy of coaching gives us the bridge to find common ground. Most of the time, our internationality is barely mentioned. Some coaches may ask for patience if English is not their first language, or perhaps more likely we request patience if the regional internet connection is not very strong. These are light reminders that we are certainly a multi-national, multi-lingual, and multi-cultural group.

However, while the emphasis on our cultural variation is not overt, there were several instances during my ICA training that got me thinking about cross-cultural communications and the subtle nuances I wanted to be more educated about.

In November 2016, soon after starting the ICA program, I heard Erin Meyer speak and quickly read her book, The Culture Map. Erin Meyer is an executive coach and a foremost expert in cross-cultural understanding. Through a combination of Meyer’s book and the case studies during training, I investigated cross cultural communication and how it relates to coaching.

Background for the research

During a recent mentor coaching session, my client let me know that she was working full-time, doing a home business, completing the ICA program, …and trying to have a successful social life. Gulp! My response? ‘That sounds…exciting.’ Clearly, ‘exciting’ was not the word that I meant. When Merci gave her evaluation, she addressed my word choice. ‘Why did you describe her situation as ‘exciting’ when she is clearly overwhelmed?’ Good question, I responded. Why did I do that?

Soon after, I joined with my study group in Beijing, two Danish women who heard this story and they exclaimed. ‘Oh that’s such an American response! A Danish person would have replied, ‘Oh you must be so depressed!’ We agreed that my American upbringing truly influenced my chosen response. It was clearly obvious to me that my client was overwhelmed and requesting help. In that moment, my default of how to be helpful to my client was to say something positive, aka ‘Be nice. Quick! Find something nice to say about that.’ And what did I come up with? ‘That sounds….exciting.’

As my study group and I delved deeper into the subject of various responses, we asked the question, why would the Danish coach’s answer be so different? ‘Oh that is clear. Because it would be more honest. Yes, the Danish person would most likely feel that the best way to be kind in that moment would be to show kindness through honesty. Be direct and tell it like it is!’

The various ways to answer a client were clearly based on cultural expectations.

On a similar point, another mentoring session brought another word of communication advice. This time, it was my tendency to say, ‘okay’ as I listened to my client and that this could be an issue. A fellow American client will likely understand that saying ‘okay’ is a verbal reflection, feedback which is meant to express, ‘Yes, I am here with you and listening to you.’ Merci reminded me that many of my foreign clients could hear ‘okay, okay, okay’ as a form of agreement. Understandably, this subconscious verbal ‘tick’ could be distracting for those who are not used to it. It is a form of interruption in many ways, yet certainly Americans are known to do some form of it throughout a conversation. It is our way of saying ‘yes, I’m listening’ not necessarily, ‘yes, I agree with you.’

Within a week’s time, my word choice and my verbal ticks were addressed as having a background in where I grew up. These two examples of explaining my response from a cultural perspective really resonated with me as I read Erin Meyer’s fascinating book on cross-cultural communication. I made the choice to be more culturally aware in my coaching, more purposeful in my setting aside of cultural expectations of where the client was coming from or what she meant by her word choice.

I decided there was a link between good coaching and someone who is multiculturally aware.

The Culture Map

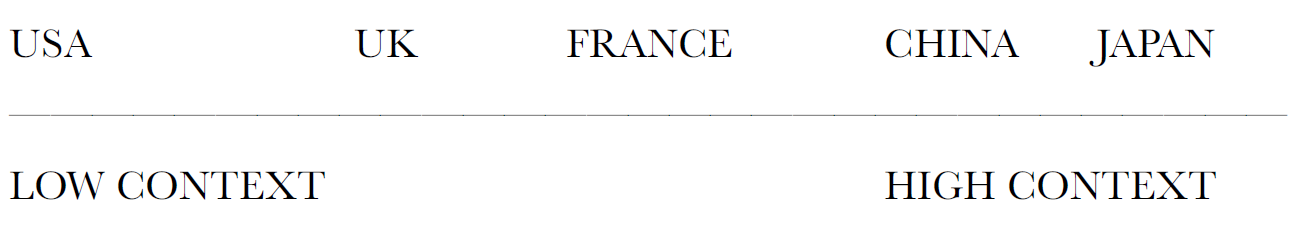

In her book, The Culture Map, Erin Meyer compartmentalizes countries into a spectrum from low-context to high-context. Low-context countries such as the United States, for example, focus on the words we say to each other and only after that do we take in the tone and the context.

In a high context culture such as where I live in China, the emphasis would be first within the context, followed by a whole host of other factors such as the hierarchy of the person speaking, the tone of their voice, and their body language, as well. In other words, the communication is much more complicated in nature.

Erin Meyer has created a linear scale to illustrate the perception of cultural communication differences.

A lot can be learned from both the high context and the low context cultures. For example, when we say that men are one way and women are another, or any other supposition we make in generalities, they are likely based on where our country lies within the high-low context grid. Perhaps a French client does not think it is so strange to have 5 children, whereas the Chinese client’s norm is one or two children. This simple example is meant to showcase only that when a coach is open and judgement free she can meet her client where the client is, instead of where her assumptions are positioned based on any one subject.

High vs. Low Context Training

Japan is the highest context country in the world. Meyer tells the story of a Japanese man who taught her about ‘reading the air.’ In Japan, there are two things said with any one word: the spoken word and the unspoken context that partners that word. A person who only hears the words a person says would be considered simple or definitely unsophisticated. In every conversation a myriad of information is given, far beyond the words spoken aloud.

This is a direct contradiction to how Americans communicate. America is the most low context country in the world. In an American work place, a person would be considered foolish were he to try to decipher everything his boss said ‘between the lines.’ That would be considered a waste of time. The responsibility for communication would be on the boss to ‘say the words clearly’ in order for her team member to understand.

As coaches, we too look for verbal ‘anchors’ or key words to focus on. We say, ‘I heard you say’ and then we ask to investigate that word more deeply. But we can also learn from the Japanese person and ‘read the air’ and understand from the context of what is being said nonverbally. In that way, we coaches say something like, ‘it seems like there are feelings of guilt here. Does that resonate with you?’ And in this way, the coach may point out and indicator that the client was not consciously aware of and identify an important point.

This ability to indicate what is being said between the lines is often the true indicator of where the clearest communication is happening.

I believe that we as coaches can learn from the high context cultures and at the same time in our efforts towards clarity, we encourage our clients towards low context communication. We want our clients to find the word that emphasizes their feeling, continually verbalizing what has not yet been said.

There is so much we don’t know

As we take on the task of coaching folks from outside our ‘home culture’ it is imperative that we acknowledge the numerous skills that entails. Furthermore, when coaches take on clients from other cultures, nationalities and ethnic norms, we become better coaches to everyone. It is my belief that the multi-culturally aware coach (MCAC) is quicker to suspend judgment and is more likely to address the client with a more open approach. An MCAC simply understands that there is so much that she doesn’t know, so she is less likely to assume.

I would argue that an MCAC is an especially empathetic coach. The subtext within the multi-cultural coaching session is something like this:

‘I have spoken to people from around the world, enough to know that things and people are different. I really must suspend judgement.’

ICA encourages coaches to be curious with all our clients. We ask questions such as, What is normal for you? Why is this important for you?

All of these questions take on a deeper level when we apply our multi-cultural awareness coaching skills. We remember that issues such as time, money, sexuality, religion, marriage, and gender are usually relative to the person who is talking about them. In our suspension of judgment, we also suspend our expectation that we know the ‘answer.’ We are more likely to ask the person, what feels right to you? What feels right in the context of your life and your culture?

Conclusion:

As we establish our routine methods as coaches, we can start our practice as a MCAC even if we only ever coach clients from our home neighborhood. The emphasis on respecting what we do not know, makes us more open to the unique and individual backgrounds of each and every client we support.

As I continue in my practice, it is my intention to continue researching and elaborating my knowledge of cross-cultural communication as I believe it makes me a better, more open coach to everyone.